Sun, Feb 22, 2026

| فارسی

Volume 28, Issue 3 (Autumn 2022)

IJPCP 2022, 28(3): 362-397 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Muzaffar Janjua M, khan A, Kamal A. Effect of Exposure to Media Images on Self-Esteem, Body Esteem, and Body Image Anxiety of College Students in Pakistan. IJPCP 2022; 28 (3) :362-397

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3705-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3705-en.html

1- University of Wah, Punjab, Pakistan.

2- University of Wah, Punjab, Pakistan. ,ayeshainam946@gmail.com

3- Vice-Chancellor at Rawalpindi Women University, Punjab, Pakistan.

2- University of Wah, Punjab, Pakistan. ,

3- Vice-Chancellor at Rawalpindi Women University, Punjab, Pakistan.

Full-Text [PDF 10885 kb]

(857 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1675 Views)

Full-Text: (1359 Views)

Introduction

The emergence and growth of social networking sites around the world began in the early 21st century. Since then, these sites have become an integral part of many people’s lives, particularly for young people. Many adults use social media applications, particularly Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram to make friends or connect with others around the world, share or learn new things, develop stronger personalities, and improve appearance and life style [1]. The body positivity media campaigns can increase the acceptance of different body sizes. Thin ideal promoting media campaign increases dislike of heavier individuals. One study claimed that self-esteem of people is enhanced after watching realistic body images in media.

Since social media has a long-lasting impact on people’s lives, it may have long-term consequences for them, but there is scant research on its mechanism. Studies have shown that social media plays a key role in women’s negative thoughts about their bodies. Social media propagates the socio-cultural ideals about ideal body shape and size, resulting in different perception of an ideal body by men and women [2]. The recent coronavirus pandemic and related lockdown has had an impact on social media use, which may be a reason for increased desire for being thin or the risk of eating disorders among adolescent and young women [3]. There has been increasing debates on whether the way social media show ideal body types is a risk factor for negative body image in both men and women, particularly in women. Body image has turned into a significant factor in one’s mental health, self-esteem, and well-being due to the increased use of social media. In western countries as well as eastern countries, the unrealistic body images are shown daily in newspapers, TV commercials, movies, and social media; these images affect the self-esteem and body image of men and women [4].

The users may upload contents in online social media to be seen by others. It is important to assess how users perceive their presence in social media. High social media use (for both posting and viewing contents) is related to lower body image satisfaction and self-esteem [5, 6]. Several studies have found that social media use is related to body esteem concerns among young adults [7, 8]. Social media show idealized images of men and women. Many of these images tend to determine specific ideals as beautiful. Thinness is emphasized for females and muscularity is emphasized for males [9]. Media users compare their bodies with these images [10]. When young adults are exposed to these media images and consider them as social norms, they start to be like them.

Pakistan is a country, where many problems and issues are health related. In spite of poverty and malnutrition, many females are unexpectedly more concerned and obsessed with their looks and physical appearance and at times this too much concentration can lead to body focused anxiety among females [11]. Pakistani fashion industry has grown enormously with modeling careers (and very thin models) becoming more visible in print and electronic media [12]. Present study aims to be the first to look at the effect media has on the self-esteem, body esteem and body focused anxiety of college students in a conservative, developing country like Pakistan.

There are different opinions about whether social media creates new fashions in a society or just reveals the existing fashions. It is suggested that people (men and women) with low body esteem are more likely to compare themselves with physically attractive people than those with high body esteem [13]. A study showed that women exposed to attractive images on social media are more likely to define themselves and their self-worth based on physical appearance [14]. Physical appearance has been as one of the predictors of self-esteem at many ages, indicating that self-esteem is linked to feelings and thoughts about body [15]. Research points out that self-esteem and body esteem are strongly related to each other among almost all young adults [16]. A meta-analysis study [17] reported that women and men of all age groups in different countries are affected by thin- and muscular-ideal internalization. The society in Pakistan, like other countries, pays more attention to the attractiveness of women and, therefore, women have worries about being rejected based on their appearance most of the time [18]. Pakistani fashion industry has had enormous growth with different types of modeling careers, where very thin models are shown in print and online media [12]. A study in Pakistan showed a significant positive relationship between body image and self-esteem in college students but the difference in terms of gender was not reported significant [12]. Results of another study indicated that women in middle age or older age are less concerned about their body image [19]. Men with low body esteem have less satisfaction when they compare their own pictures with the pictures of men with ideal body type [20]. Social media has become popular among young adults; therefore, its excessive use may cause adverse behaviors among them [21].

Body image anxiety or body image dissatisfaction, refers to one’s dissatisfaction with body image and physical appearance [22]. Low body esteem in young adults often leads to experiencing body image anxiety, Research suggests that high exposure to the media may be associated with body image anxiety in young men and women [23]. Mass Media often provide information about idea physical appearance like slim body for women and muscular male body which leads to internalized ideal body standard propagated by media [7, 24].

Media can develop many disorders related to body image, size, and appearance which in turn can lead to low body satisfaction and produce a gap between ideal and actual body image [25, 7, 26]. The more one reads or watches something related to the appearance, the more psychological pressure and negative body image s/he will have, which leads to body image anxiety [27, 28]. Furthermore, those who follow the celebrities on social media are more likely to have depressive symptoms and body image anxiety [15]. Females are more likely to reduce their weight after exposure to social media images of thin models and being criticized by parents, relatives, and friends [29]. The findings of a recent study in Pakistan reported the impact of family pressure, peer pressure and media pressure on body image dissatisfaction among female workers [30]. Parents’ pressure verbally or by active encouragement has been shown to have more impact on their children’s (at any age) body image concerns than the social media models. Both mothers and fathers are key sources of influence on the children’s body image [31], in addition to the media [32]. Results of a study indicated that parents’ educational level and family type (joint or nuclear) affect the body esteem and body image in children [33].

Another influencing socio-cultural factor of body image anxiety is the socioeconomic status. Previously, it is believed that body image anxiety is more prevalent among young adults from upper-class communities, but few studies have claimed that body image anxiety is not limited to people from upper class and people belonging to lower class can also have body image anxiety [34]. Despite poverty and malnutrition, many women are concerned about their physical appearance which can lead to body image anxiety among them. In Pakistan, government-owned institutions are Urdu medium and traditional, and use English as a separate medium, while private institutions are English medium and mostly follow the traditions of Western countries in education and ruling. These two types of institutions reflect differences in the socio-economic level of students in Pakistan, where the former represents the lower-class communities and the latter represents the upper-class communities. Students from the English-medium institutions have greater body image anxiety than the students from Urdu-medium institutions [35].

Although many studies have investigated the effects of social media on body esteem and body image dissatisfaction of women, very few studies have investigated the extent of its effect on the body image of men, especially male college students in Pakistan. Therefore, there is a need to investigate how the body image of male college students in Pakistan is affected by exposure to images represented on social media as ideal. Present study will also investigate the difference among individuals’ perceptions about study variables belonging to different family systems. It is assumed that desired results will be founded from present research as the literature strongly supports the proposed model.

Study objectives and hypotheses

The present study aims to investigate the effects of social media on male and female college students’ self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety and examine the gender differences. The study hypotheses are formulated as follows:

• Students with exposure to the images of thin/muscular models have lower levels of self-esteem than those with exposure to middle-sized/non-muscular model images.

• Students with exposure to the images of thin/muscular models have lower levels of body esteem than those with exposure to middle-sized/non-muscular model images.

• Students with exposure to the images of thin/muscular models have higher levels of body image anxiety than those with exposure to middle-sized/non-muscular model images.

Methods

Study design and participants

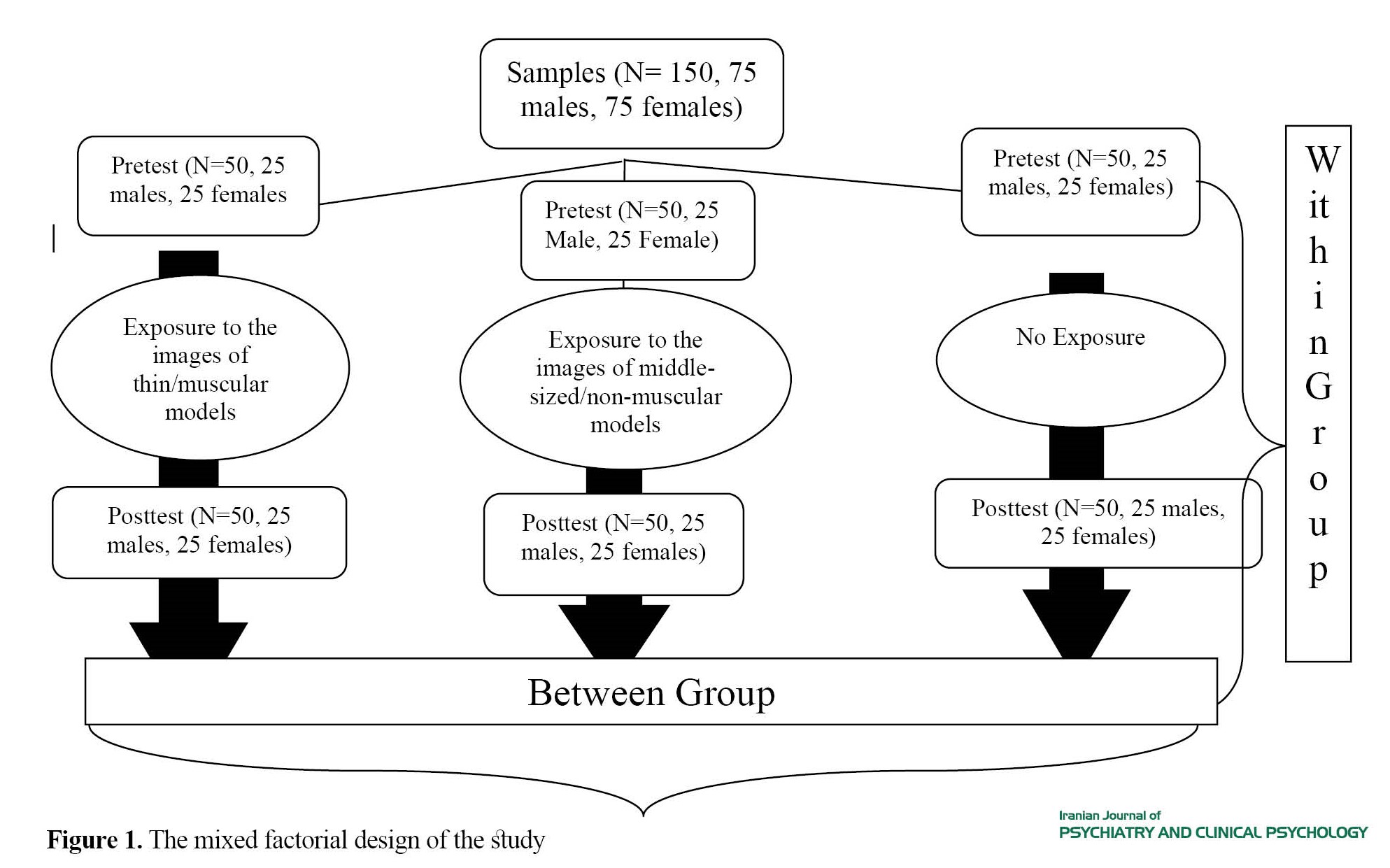

This is an experimental study with a pretest/posttest design. A mixed factorial design was used in order to minimize the limitations. Therefore, within -group and between-group designs (randomized, matched and factorial) were used. The overall design was as: 2 (Phases: pretest and posttest) × 3 (Conditions: exposure to the images of thin models, exposure to the images of middle-sized models, and no exposure) × 2 (Gender: male and female). The independent variable was the exposure to images of models.

Sample was selected by a purposive sampling method from college students of governmental model colleges for boys and girls in Islamabad, Pakistan (N=150, 75 females and 75 males, aged 18-25 years) (Figure 1). College students was targeted as the study population because literature suggests that young adults are more concerned about their appearances and suffer more from body image anxiety compared to children and adults [36, 37, 38]. Initially data was collected from 40 individuals per group. After removing the questionnaires with missing data, 25 samples in each group remained. In experimental studies, the researcher needs to control all the variances; hence, a small sample size is better for effective manipulation [39]. Using the G*Power software, version 3, the sample size was obtained 25 for each group. Inclusion criteria were: a moderate body mass index (BMI=20-24.99 Kg/m2) [40, 41], being a student in Government model Colleges, and age 18-25 years. Exclusion criteria were: A BMI below or above average, being a student from private colleges, and age <18 or >25 years.

Samples were randomly assigned to three groups with equal number of individuals: (1) Group I: females exposed to the images of slim/thin female models and males exposed to the images of muscular male models, (2) Group II: females exposed to the images of middle-sized female models and males exposed to the images of non-muscular male models, (3) Control group: not exposed to the images of any models. At the pretest phase, they completed self-report questionnaires to measure their self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety. At the posttest phase, a three-week interval was used to avoid the effect of changes in performance due to practice or fatigue. Then, the two experimental groups exposed to the images on social media and then were asked to fill the self-report questionnaires once again. The control group completed the questionnaires without exposure to any images on social media.

Instruments

Following instruments were used in the present study.

State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES)

It has 20 items and three subscales: Performance Self-Esteem (7 items), Social Self-Esteem (7 items) and Appearance Self-Esteem (6 items). Only Social Self-Esteem and Appearance Self-Esteem subscales (13 items) were used in the present study. Performance Self-Esteem Subscale was excluded as it was not related to the study objectives. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale as 1= Not at all, 2= A little bit, 3= Somewhat, 4=Very Much and 5= Extremely). Some items have reversed scoring (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10 and 13 in the current study). The reliability of the overall scale is α=0.92, and the reliability of performance, social and appearance subscales are 0.64, 0.60 and 0.55, respectively.

The Body Esteem Scale (TBES)

It has 35 items and three subscales for males and three subscales for females. Subscales for males are physical attractiveness (11 items), upper body strength (9 items) and physical condition (13 items). Subscales for female are sexual attractiveness (13 items), weight concern (10 items), and physical condition (9 items). The items are scored on a 5-point scale as 1= Strong negative feelings, 2= Moderate negative feelings, 3= No feeling one way or the other, 4= Moderate positive feelings, and 5= Strong positive feelings. Higher scores indicate more favorable body esteem, while lower scores indicate less favorable body esteems. The reliability of TBES ranged 0.78-0.87.

Physical Appearance State and Traits Anxiety Scale (PASTAS) [42]: It has two versions, the Trait Version and the State Version. In present study, the State version was used which has 16 items scored on a 5-point scale as 1= Not at All, 2= Slightly, 3= Moderately, 4= Very much so, and 5= Exceptionally so. The reliability of PASTAS ranged 0.82-0.92. High scores indicate high level of anxiety and tension about body.

After obtaining informed consent from the participants, they were invited to complete the questionnaires in three different classrooms. In each classroom, there were two researchers as instructors. After completion of the questionnaires, the participants were informed that they need to complete the questionnaires again after 3 weeks.

Stimulation

After three weeks, the participants were exposed to the experimental stimuli in the lab. Participants were exposed to the images using multimedia projectors. Each image was displayed for 45 seconds because the researcher wanted to record the state condition of participants. For female participants,fiveprint images of thin and middle-sized female models were used for the stimulation. Images were edited in Photoshop to make thin models look middle-sized. Female respondents were asked two questions about each five images according to the method proposed in a previous study [43]. The first question was: “Please rate the attractiveness of the model in the image”. Responses were based on a 7-point scale ranged from 1= Very unattractive to 7=very attractive. The second question was: “How do you perceive the size of the model in the image? Responses were recorded based on a 7-point scale ranged from 1=Very thin to 7= Very thick”.

For the stimulation of male participants, five print images of muscular/non-muscular models were used. Images were edited in Photoshop to make non-muscular models to look muscular. They were asked two questions about each five images. The first question was: “Please rate the attractiveness of the model in the image”. Responses were based on a 7-point scale from 1= Very unattractive to 7= Very attractive. Second question was: “How do you perceive the size of the model in the image?” Responses were based on a 7-point scale from 1= Very lean to 7= Very muscular.

It was kept confidential that what type of exposure they were given. Participants in the control group did not receive any kind of experimental manipulation and were not informed about the treatment given to other two groups. After experimental manipulation in the experimental groups, participants of all groups including control group were asked complete the three questionnaires.

Data analysis

For comparing the different groups, the 2×3×2 mixed factorial design was used. Along with descriptive statistics, independent t-test was used to examine the gender differences. Mixed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the differences among experimental conditions. In checking the normality of data distribution, the values of skewness and kurtosis were within normal range and the scores of all questionairs were normally distributed.

Results

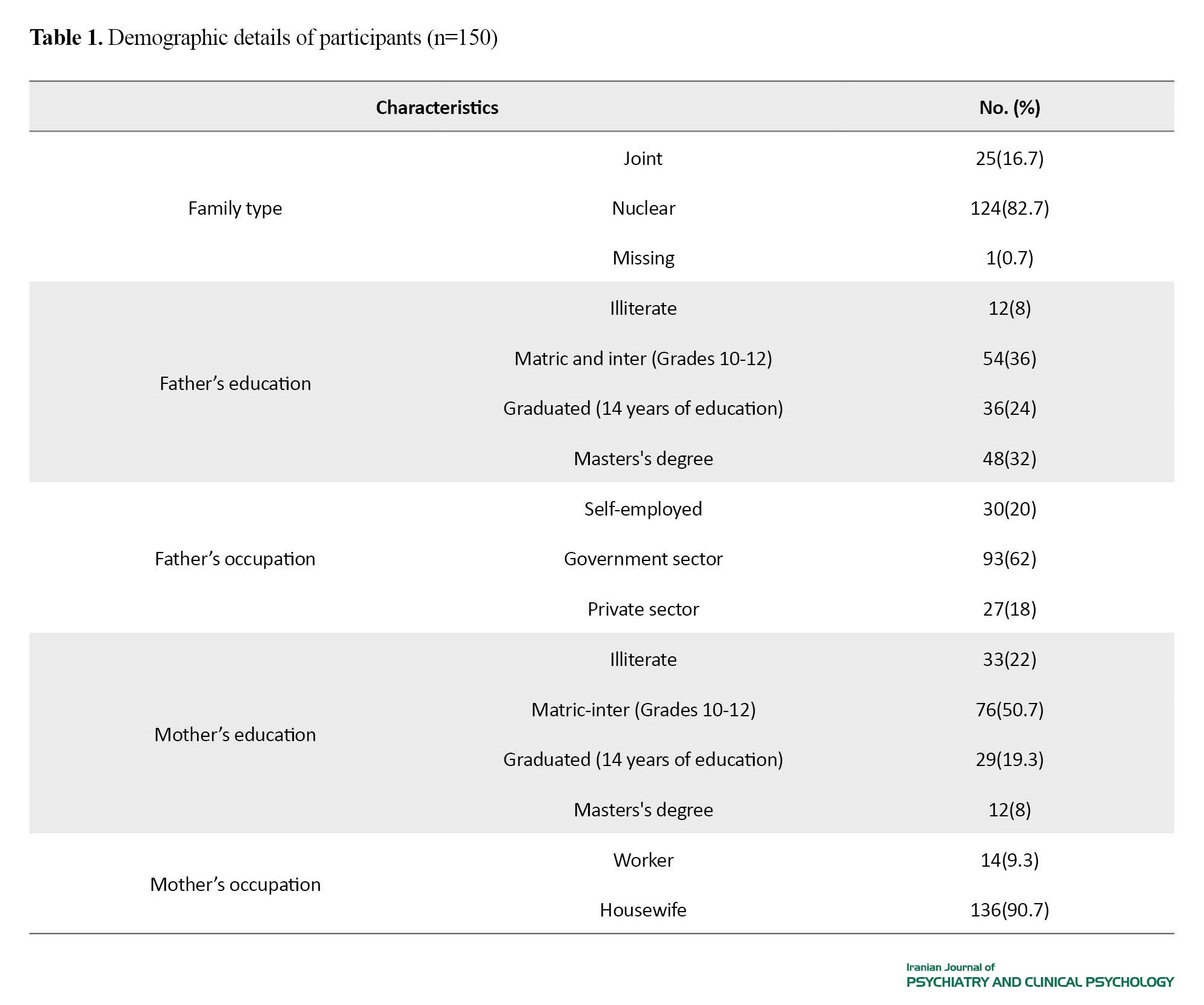

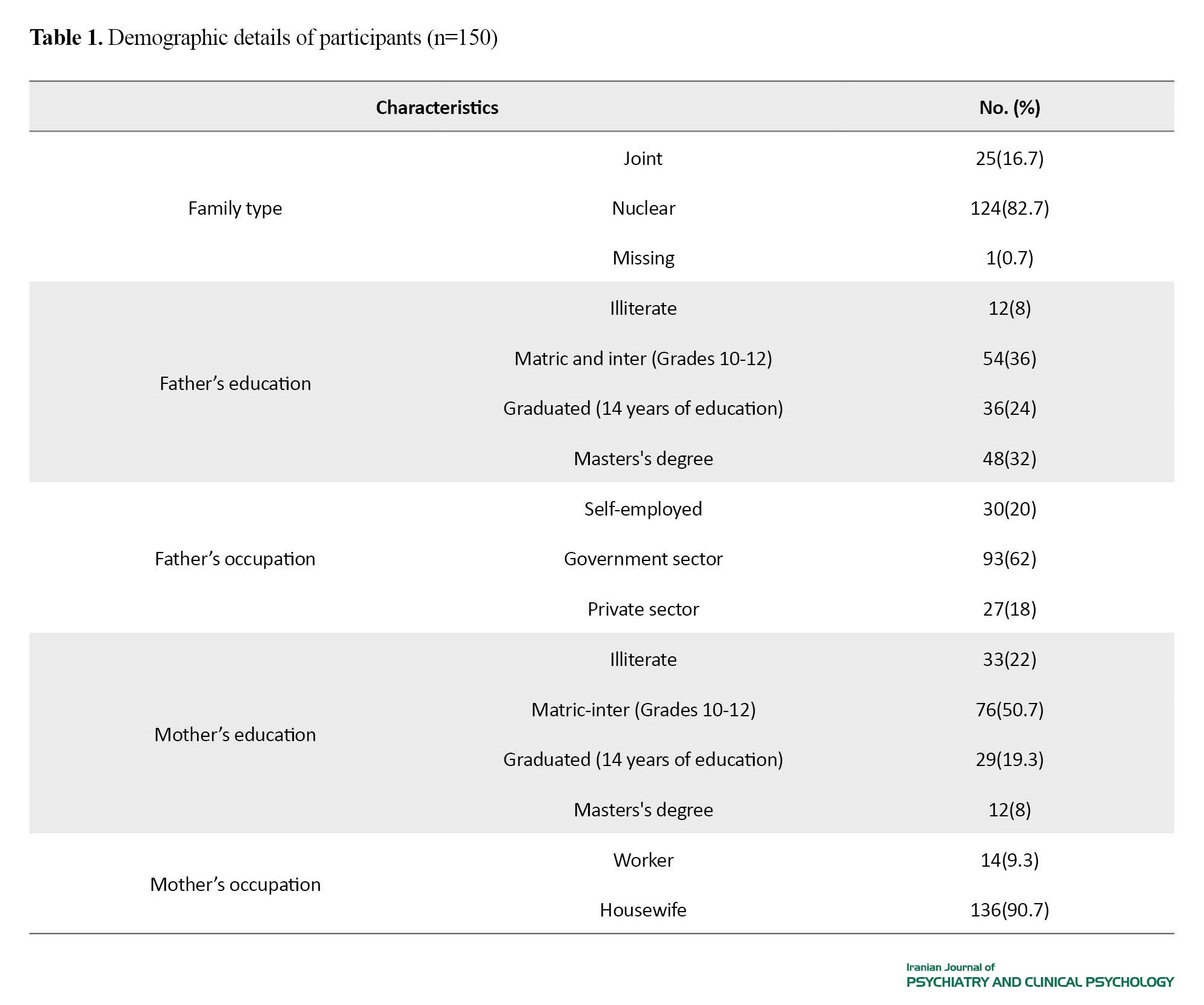

There were 50 participants in each group (25 males and 25 females). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of participants using frequency and percentage.

As can be seen, the educational level of the parents of students was at moderate level. Moreover, 85% of participants had an age of 18-20 years, 50% had 1-3 siblings, and 82% were from nuclear families.

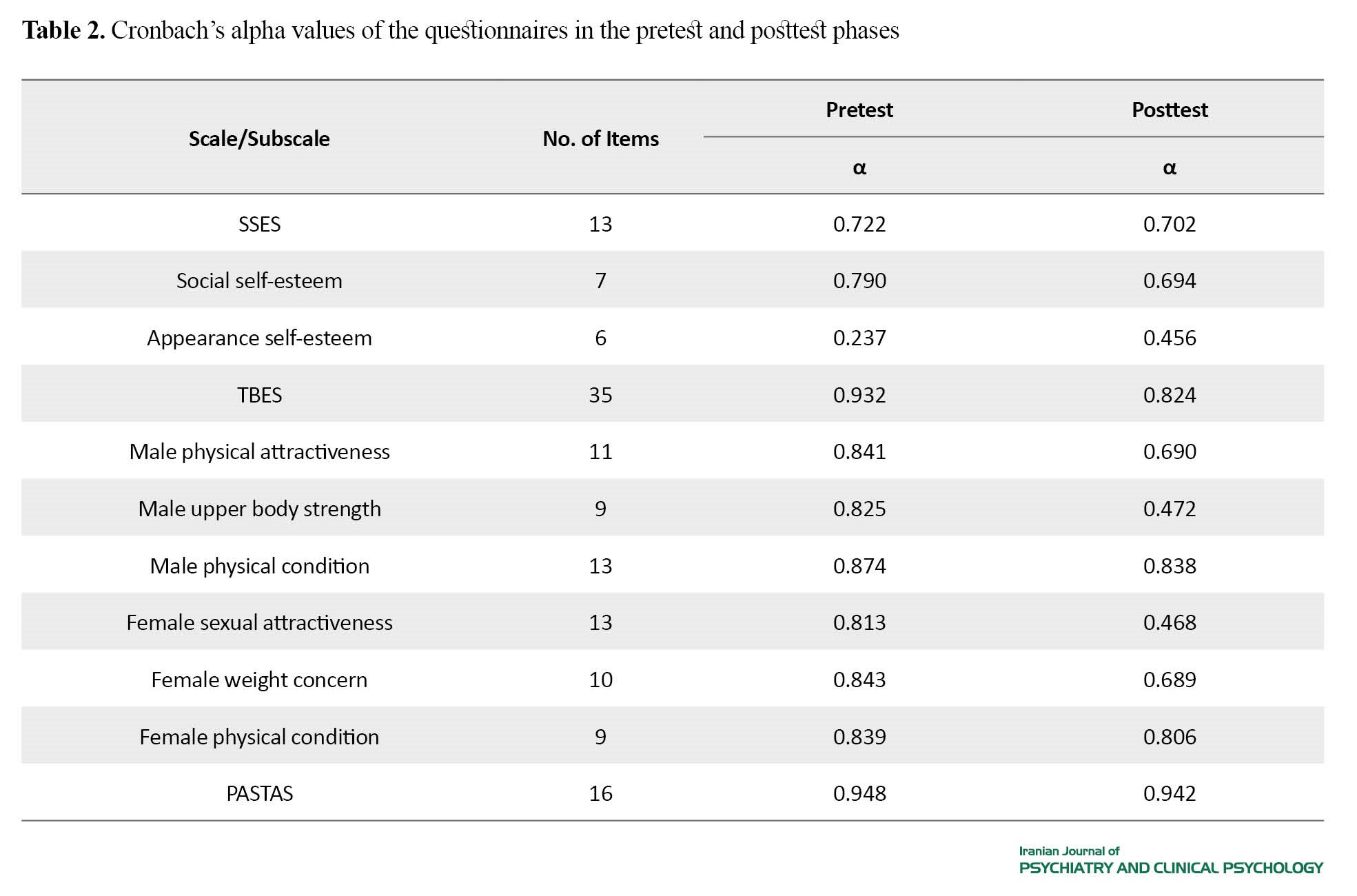

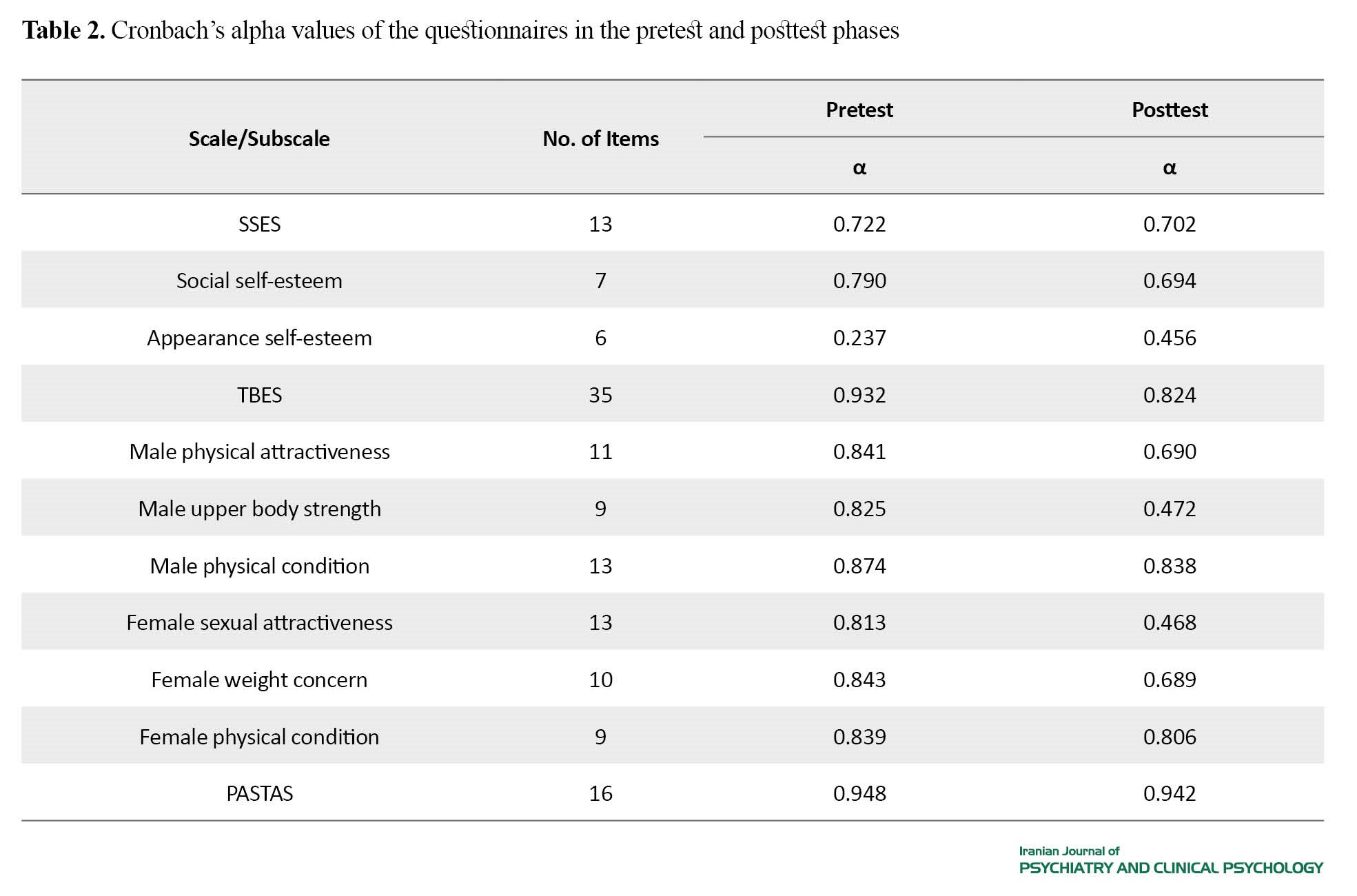

Internal consistency of the questionnaires

Internal consistency of the Pakistani version of three questionnaires was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. As can be seen in Table 2, the Cronbach’s alpha values of TBES and PASTAS were very high, indicating that they had high internal consistency.

For the SSES and its subscales, the results indicated the moderate internal consistency in both pretest and posttest phases. The upper body strength subscale for males and sexual attractiveness subscale for females in TBES showed a decline in the posttest phase, indicating that it is affected by the experimental treatment.

Examining gender differences

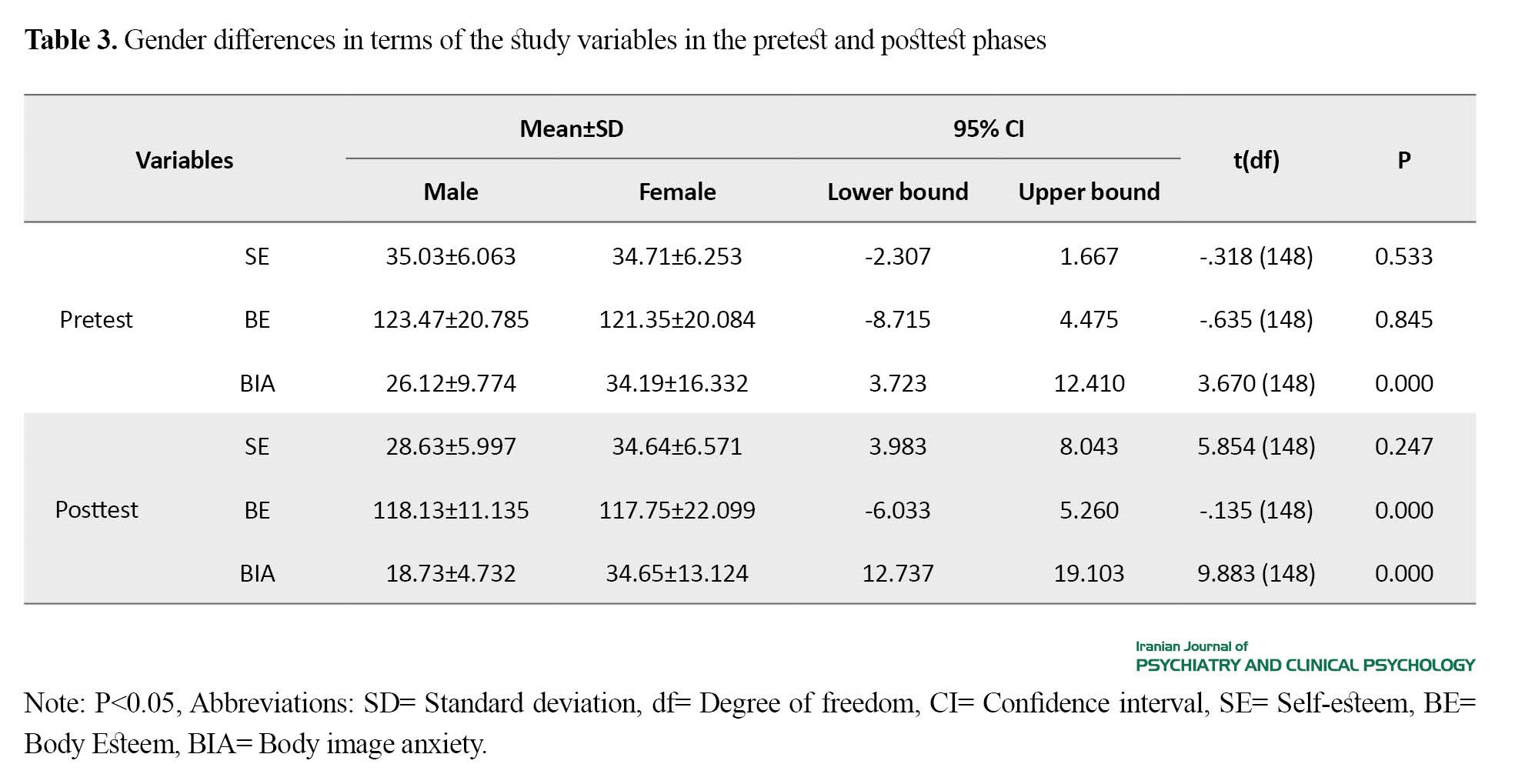

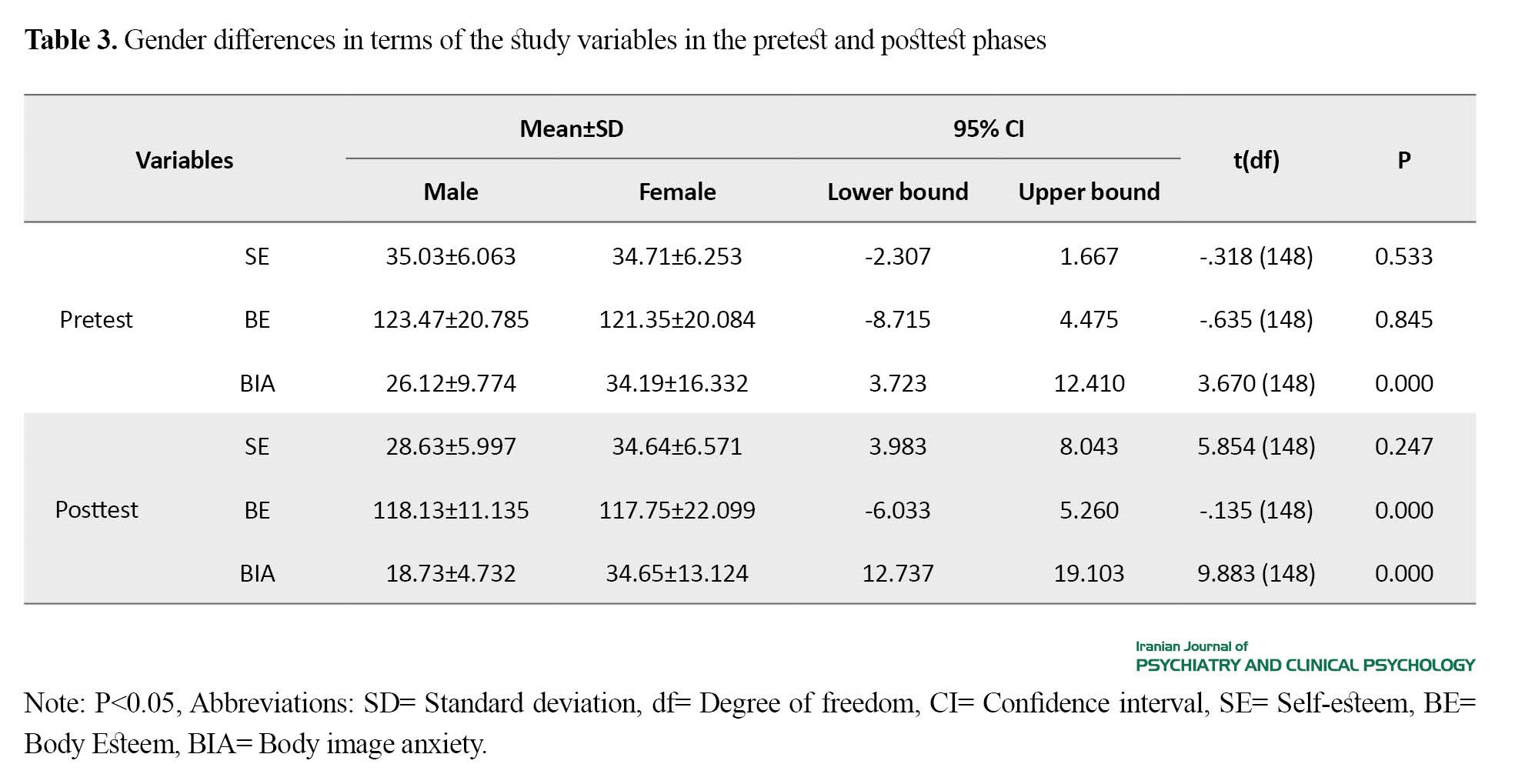

To examine gender differences in terms of the study variables, independent t-test was conducted. Table 3 represents the mean scores of three variables (Self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety) for male and female samples.

The results indicated a statistically significant difference between males and females in both pretest and posttest phases.

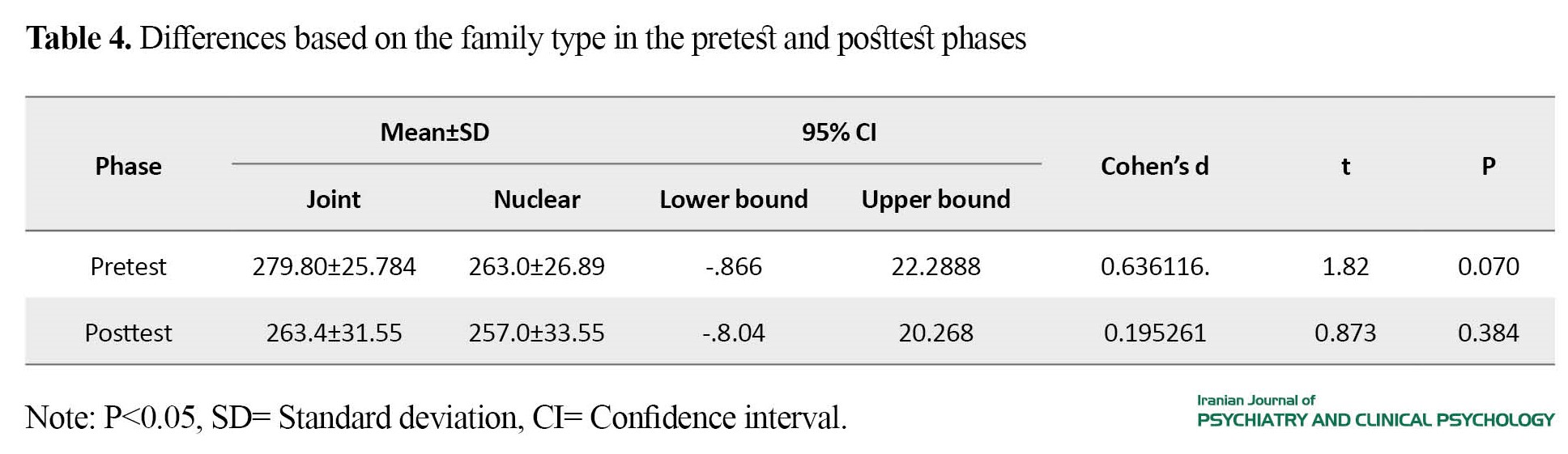

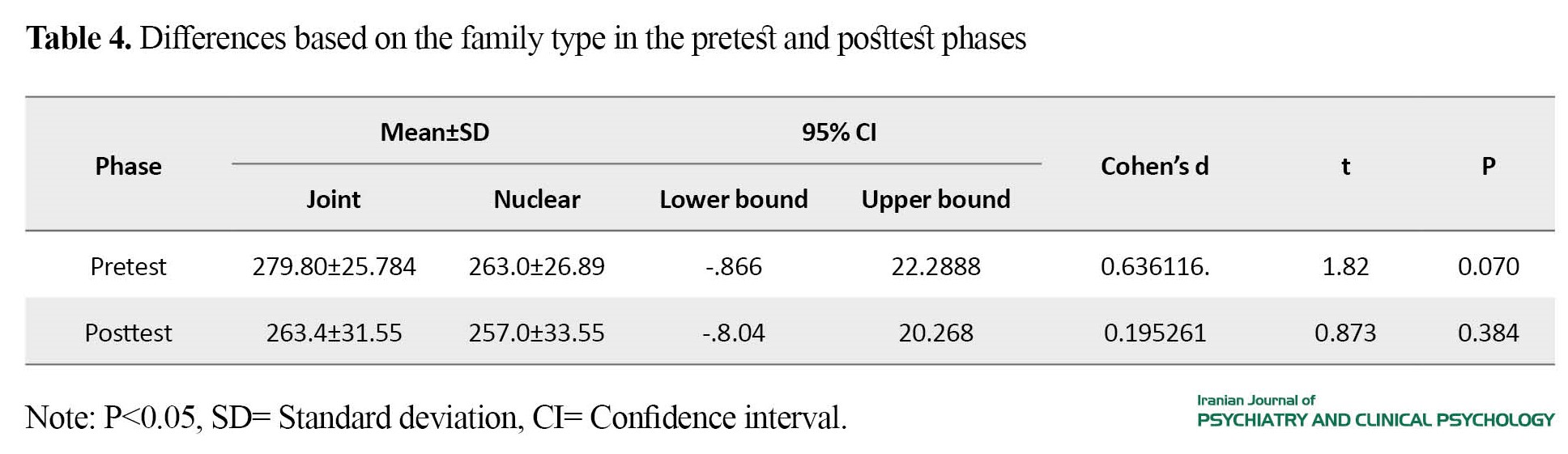

Examining differences based on the family type

For examining the differences based on the family type (joint and nuclear) in the study variables, independent t-test was conducted. A statistically significant difference between the two types of families were found in terms of the study variables in both pretest and posttest phases (Table 4).

It indicates the significant change after exposure to the images.

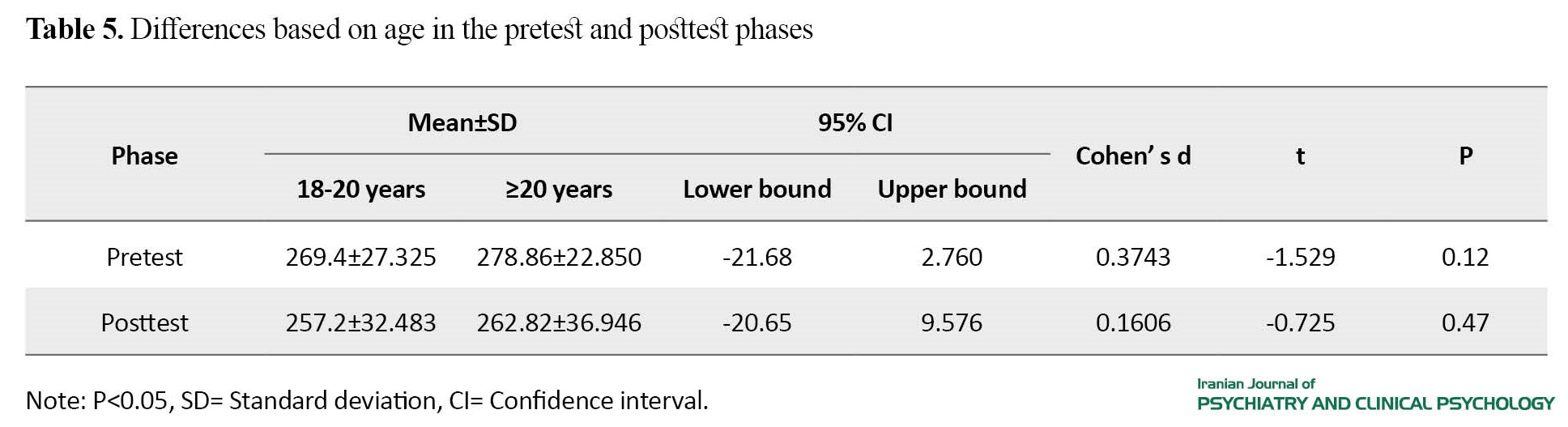

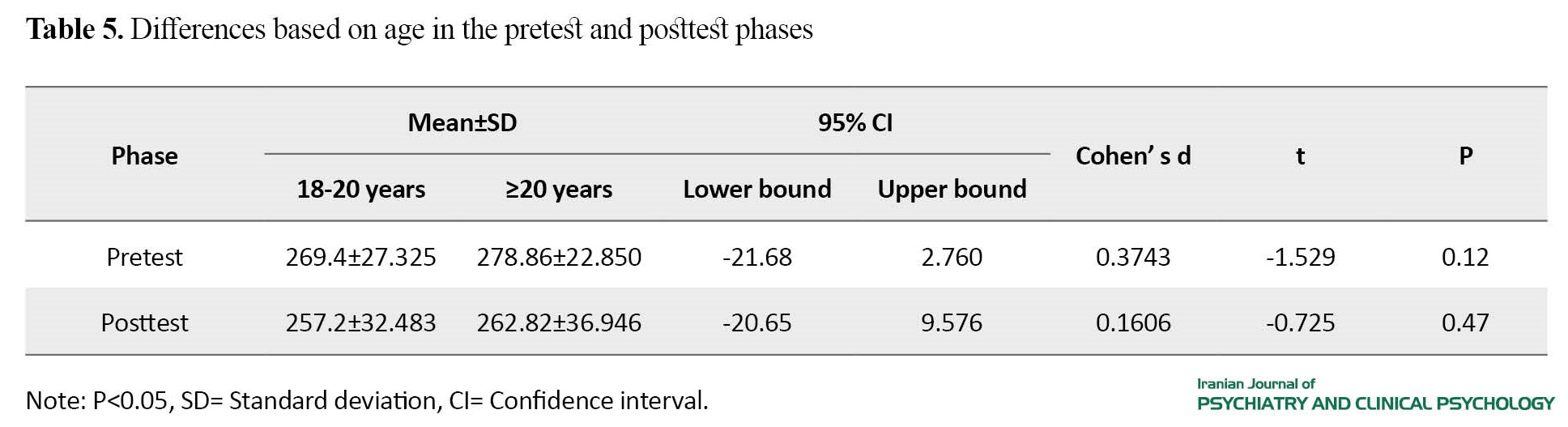

Examining differences based on age

Independent t-test was used to eaxamine the differences in the study variables based on age (18-20 and ≥20 years) in the pretest and posttest phases. The results in Table 5 showed a significant difference between the two age groups.

It indicates the significant changes in scores after exposure to the images.

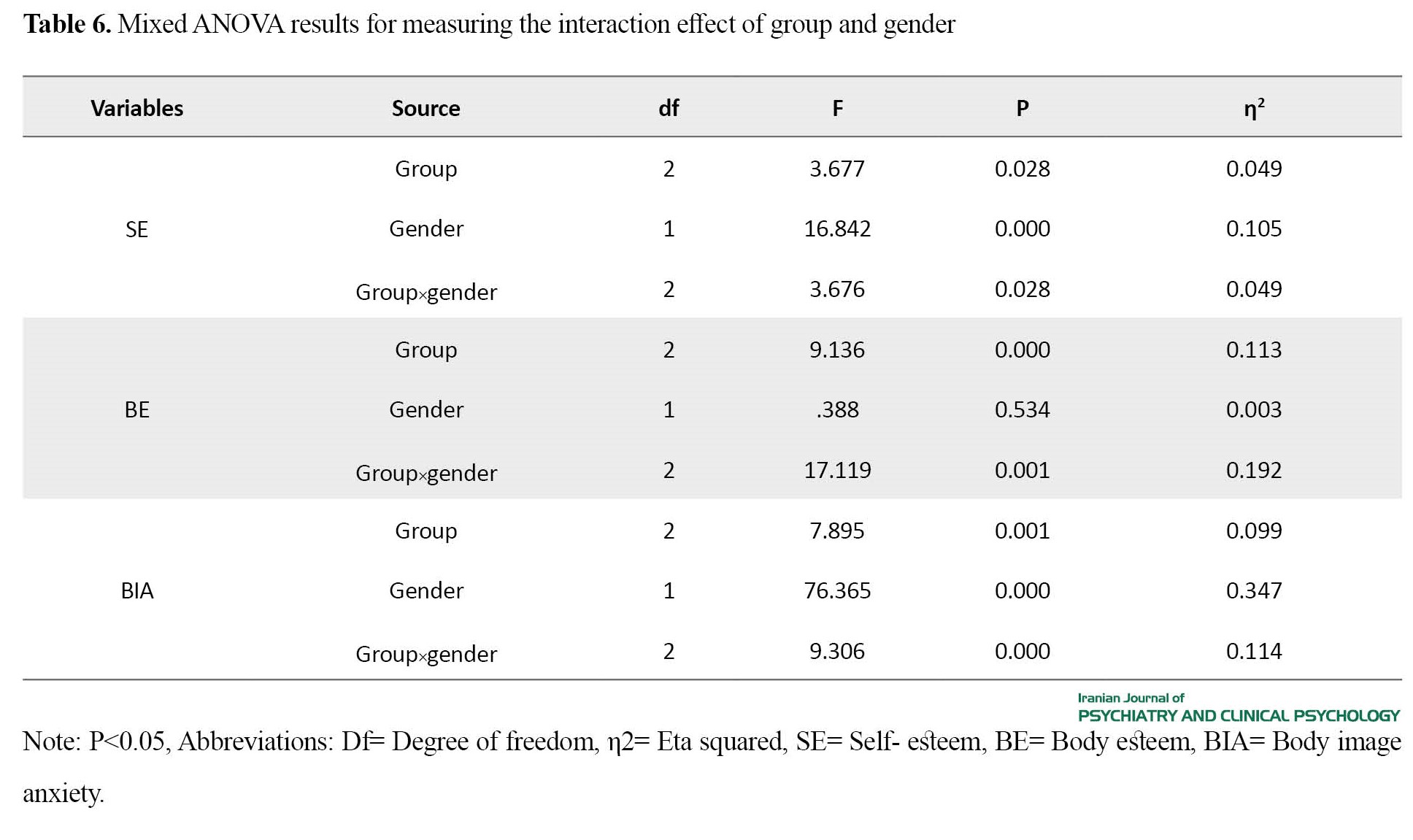

Effects of group, gender, and age on the study variables

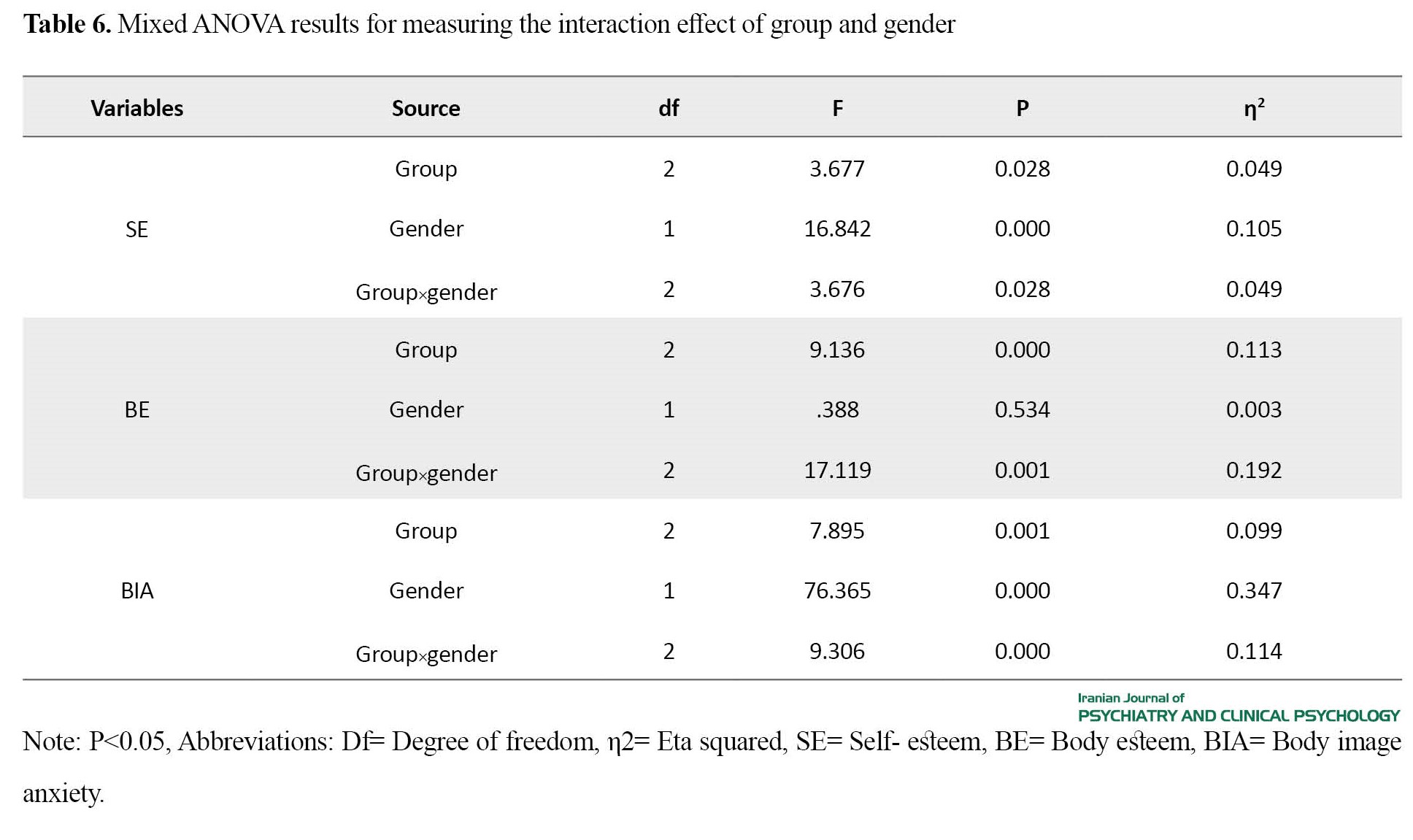

Mixed ANOVA was used to examine the effects of group, gender, and age on the study variables (self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety). The results in Table 6 indicated the statistically significant interaction effect of gender and group on the self-esteem (F(2,144)=3.676, P<0.028).

Regarding the body esteem, the interaction effect of gender and group was also significant (F(2,144)=7.119, P<0.000). The results in Table 6 indicated that interaction effect of gender and group on body image anxiety was also significant (F (2, 144) = 9.306, P<00).

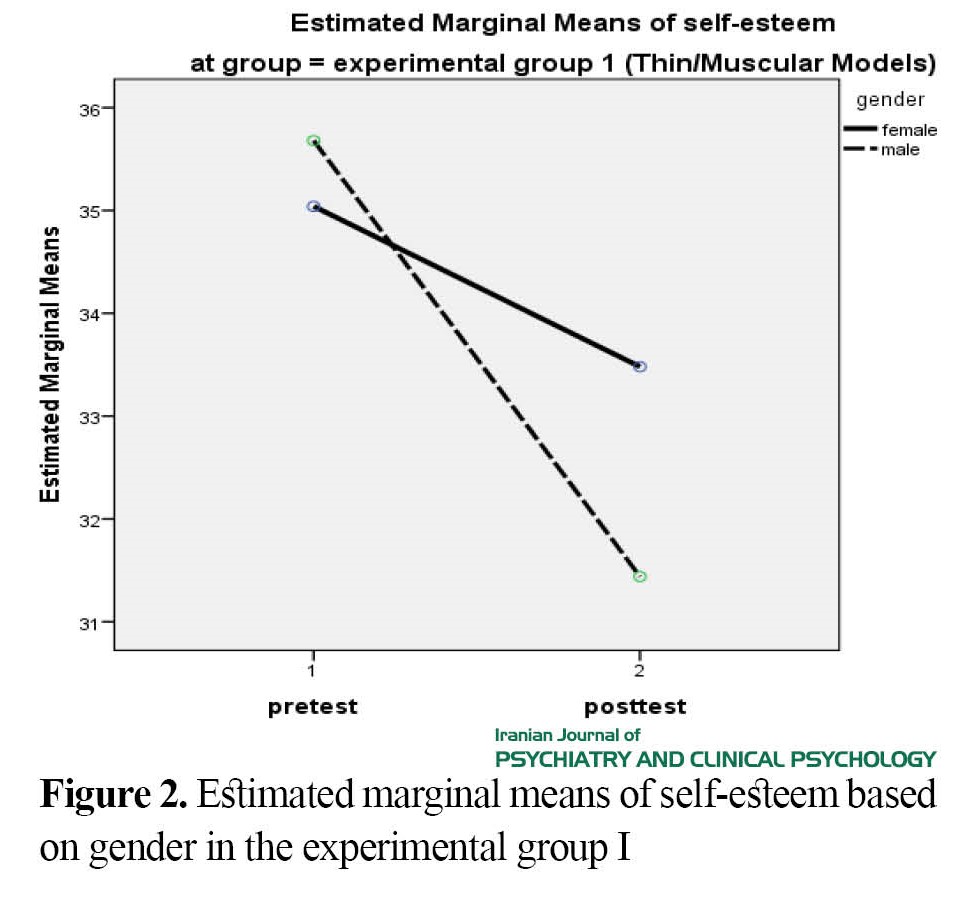

Figure 2 showed that the self-esteem of male students was highly declined in the posttest phase in the experimental group I where they were exposed to the images of muscular male models. Compared to male students, females showed less difference in the self-esteem from the pretest to posttest phases.

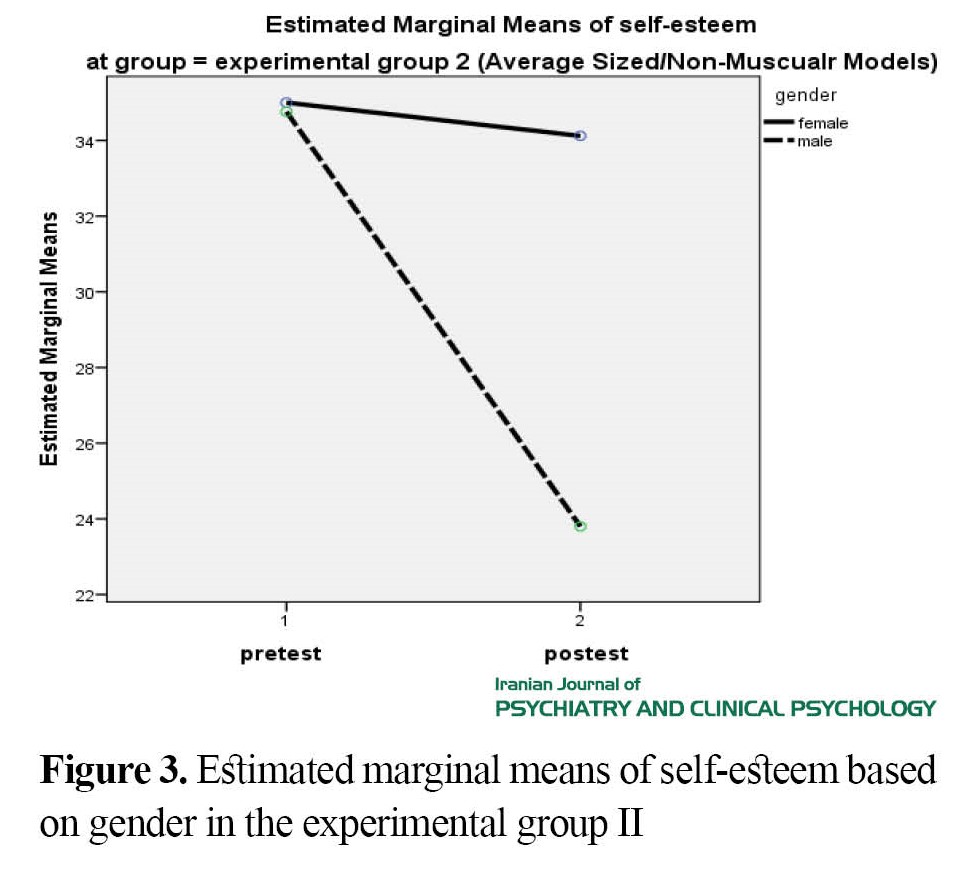

Figure 3 showed that male participants had relatively low self-esteem in the experimental group II where they were exposed to the images of non-muscular male models. However, the self-esteem of female participants remained relatively stable after being exposed to the images of middle-sized models.

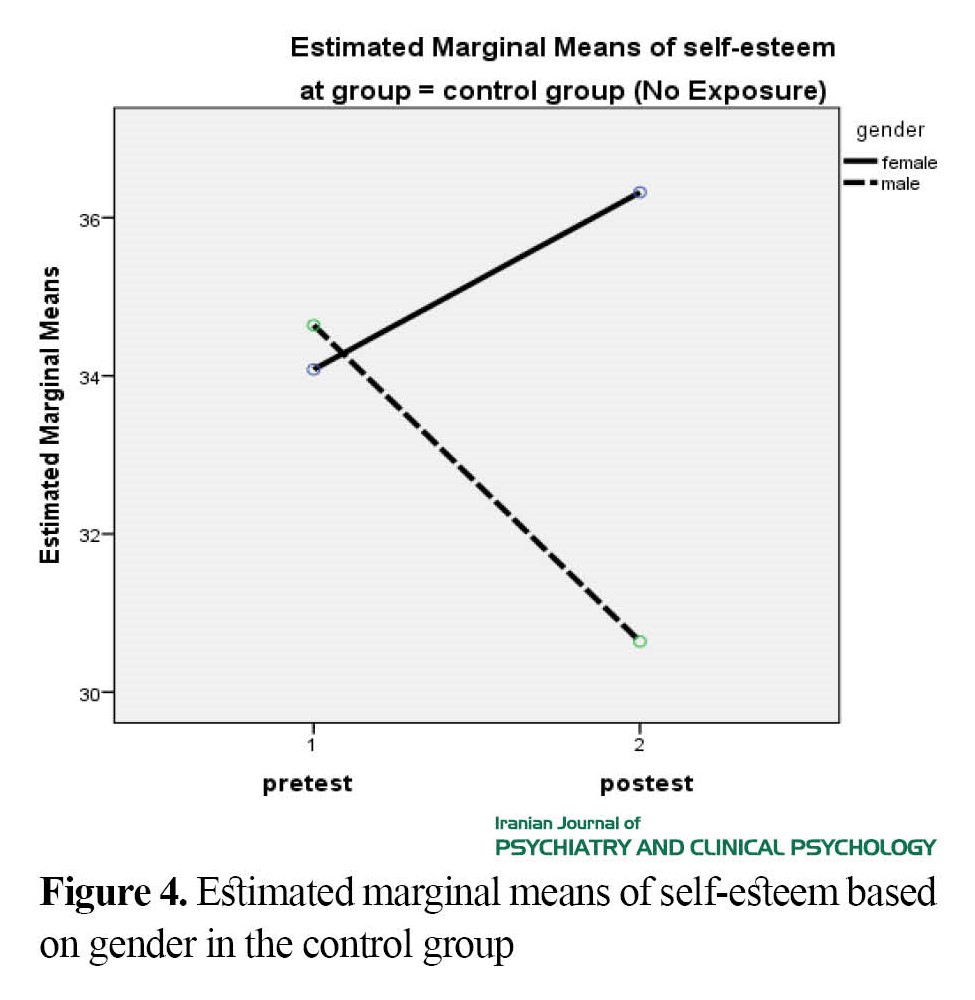

Figure 4 showed that, in the control goup, the level of self-esteem increased in female participants and decreased in male participants in the posttest phase. In overall, it can be concluded that the self-esteem of students (both males and females) in the experimental group I were significantly decreased after exposure. However, the change in the scores of male participants was significantly higher compared to female participants.

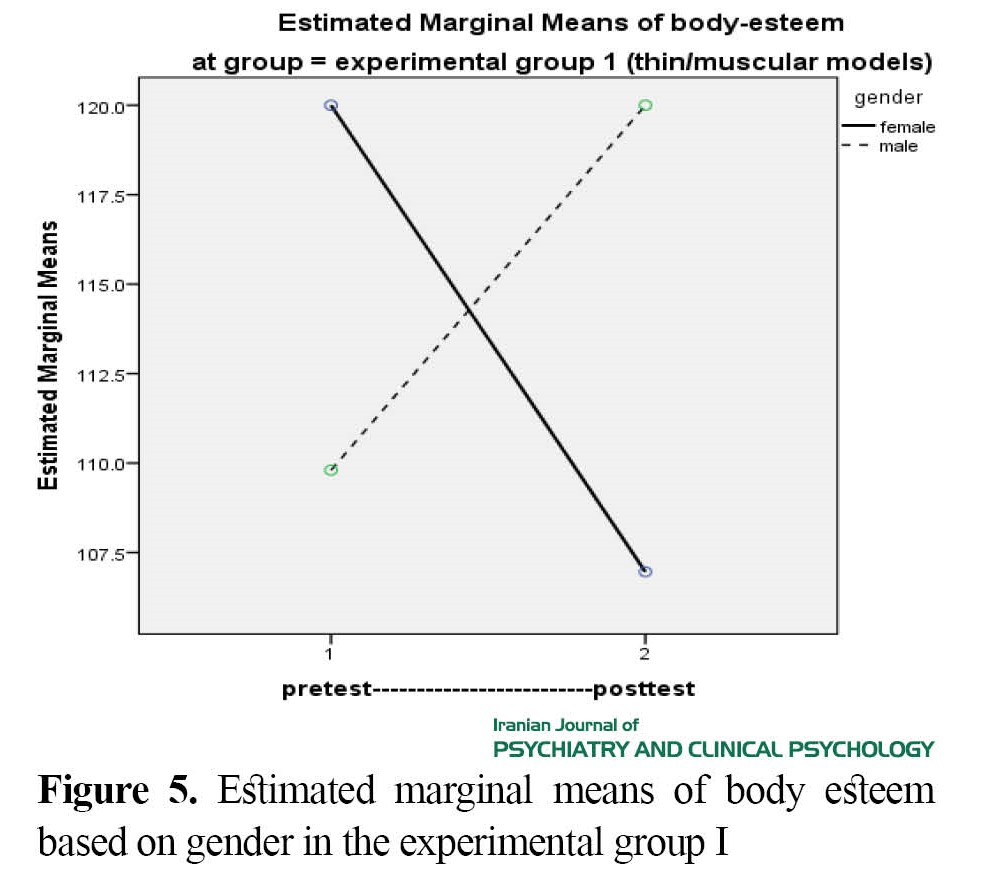

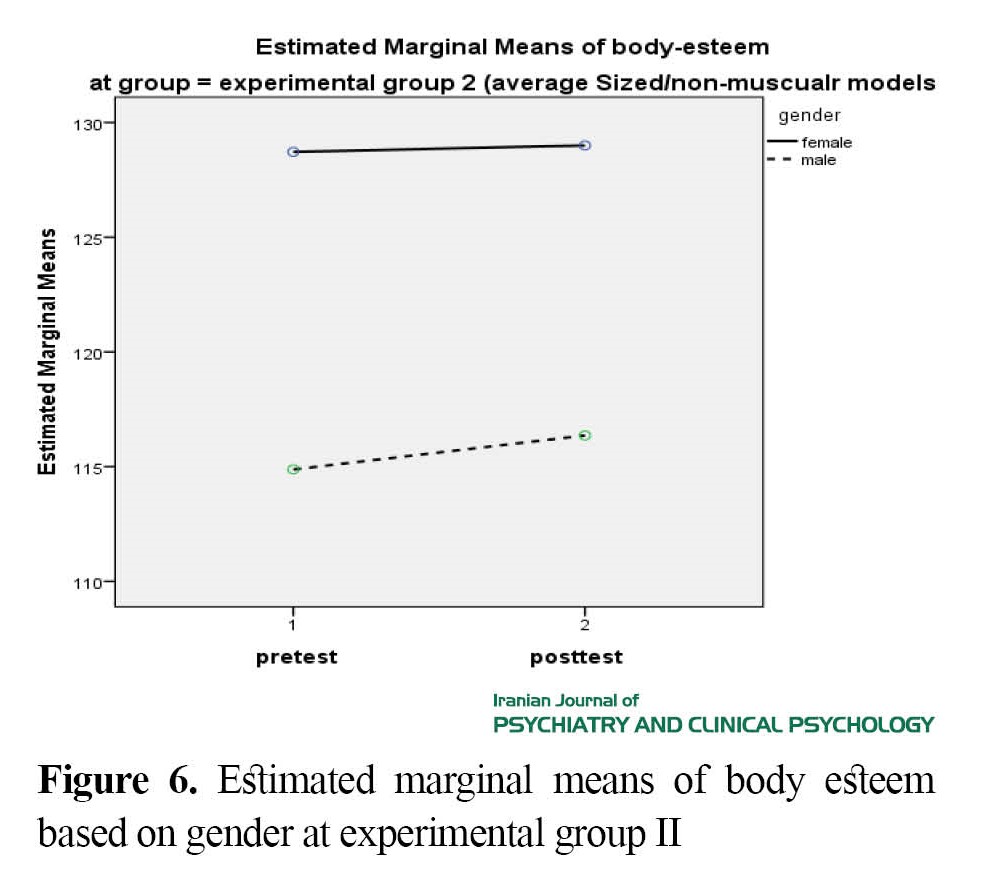

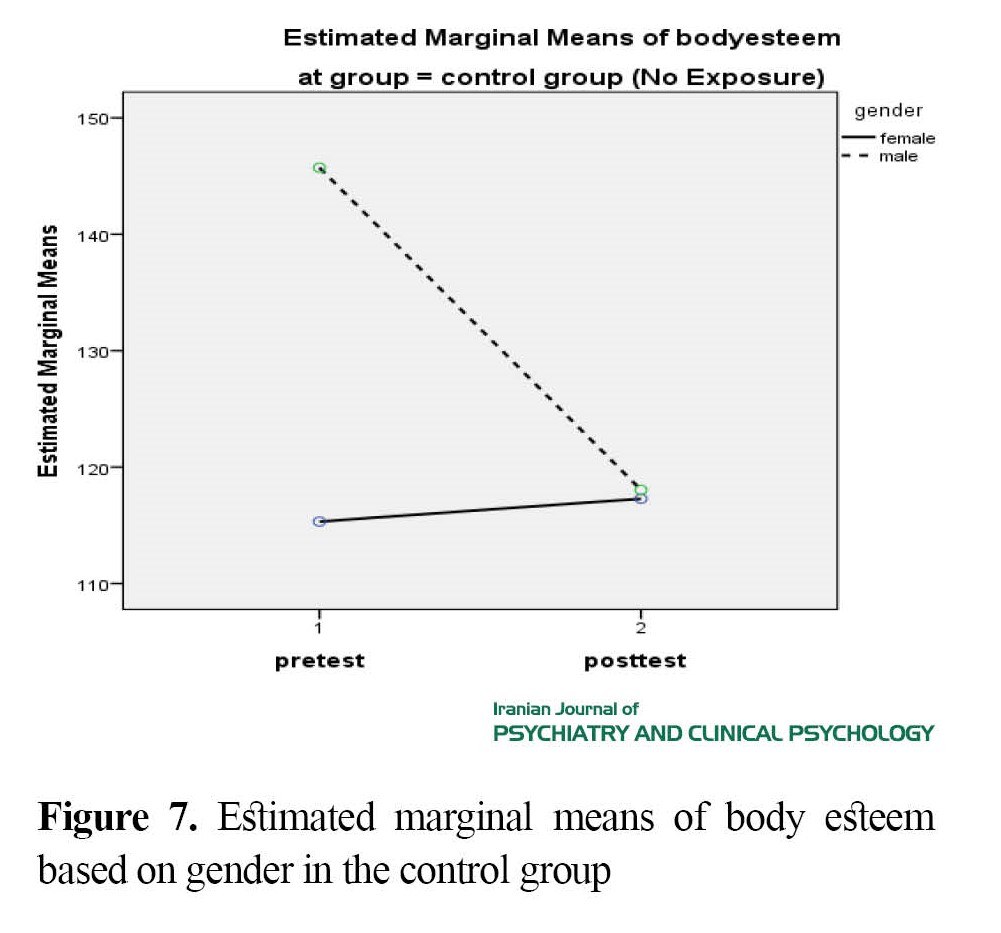

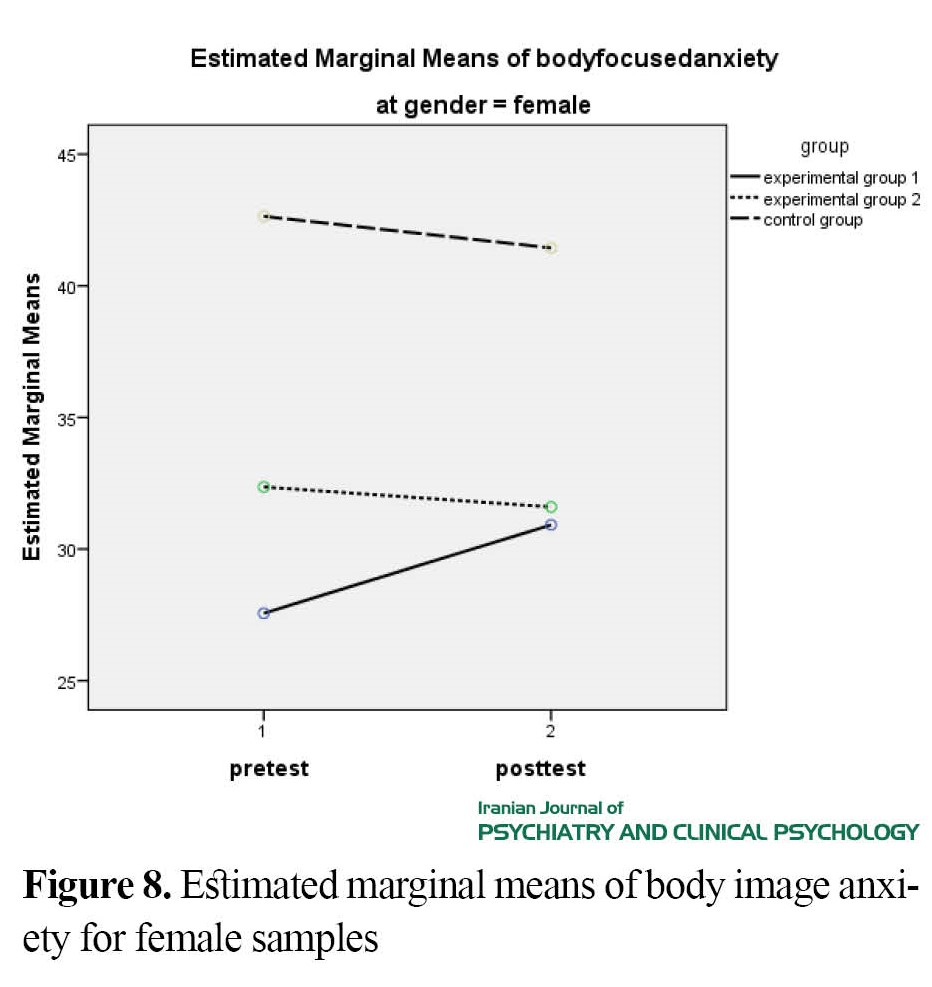

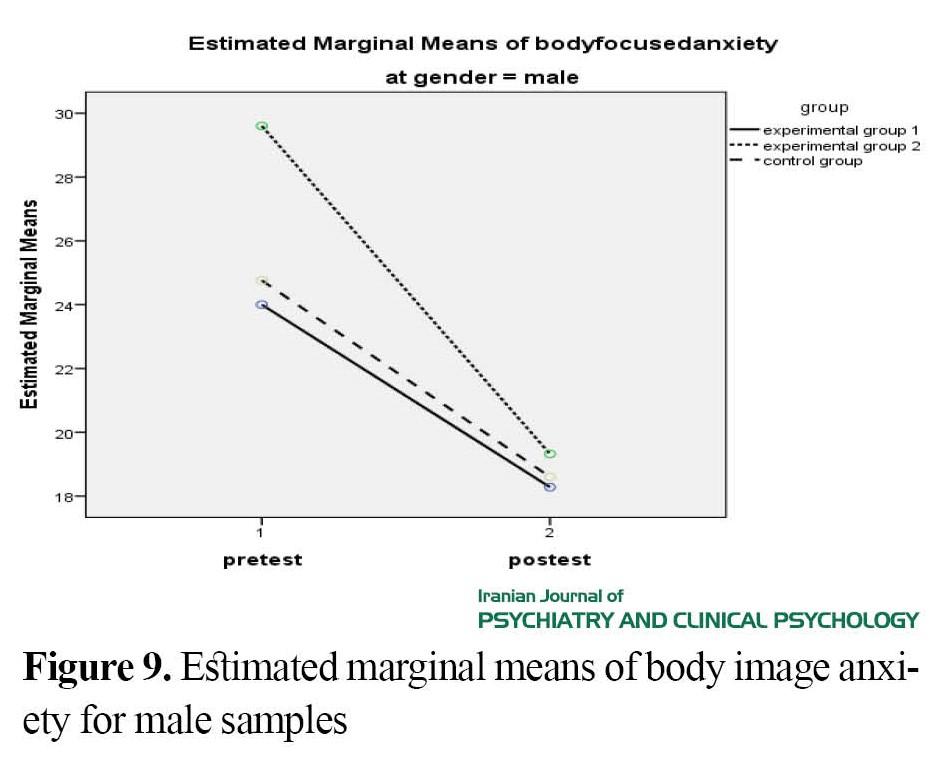

In Figure 5, the scatter plot showed that the body esteem of female participants in the experimental group I decreased after exposure to the images of middle-sized female models, while the scores of male participants increased after exposure to the images of non-muscular models. Figure 6 showed that body esteem remained almost the much same for both male and female participants in experimental group II (exposed to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models). Figure 7 showed that male participants in the control group showed a decreased body esteem, while female participants’ body esteem remained almost unchanged. In overall, the body esteem of female participants in all groups remained stable, but male participants in the experimental group II (exposure to the images of middle-sized/ non-muscular models) and control group (no exposure) showed a high decrease in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase.

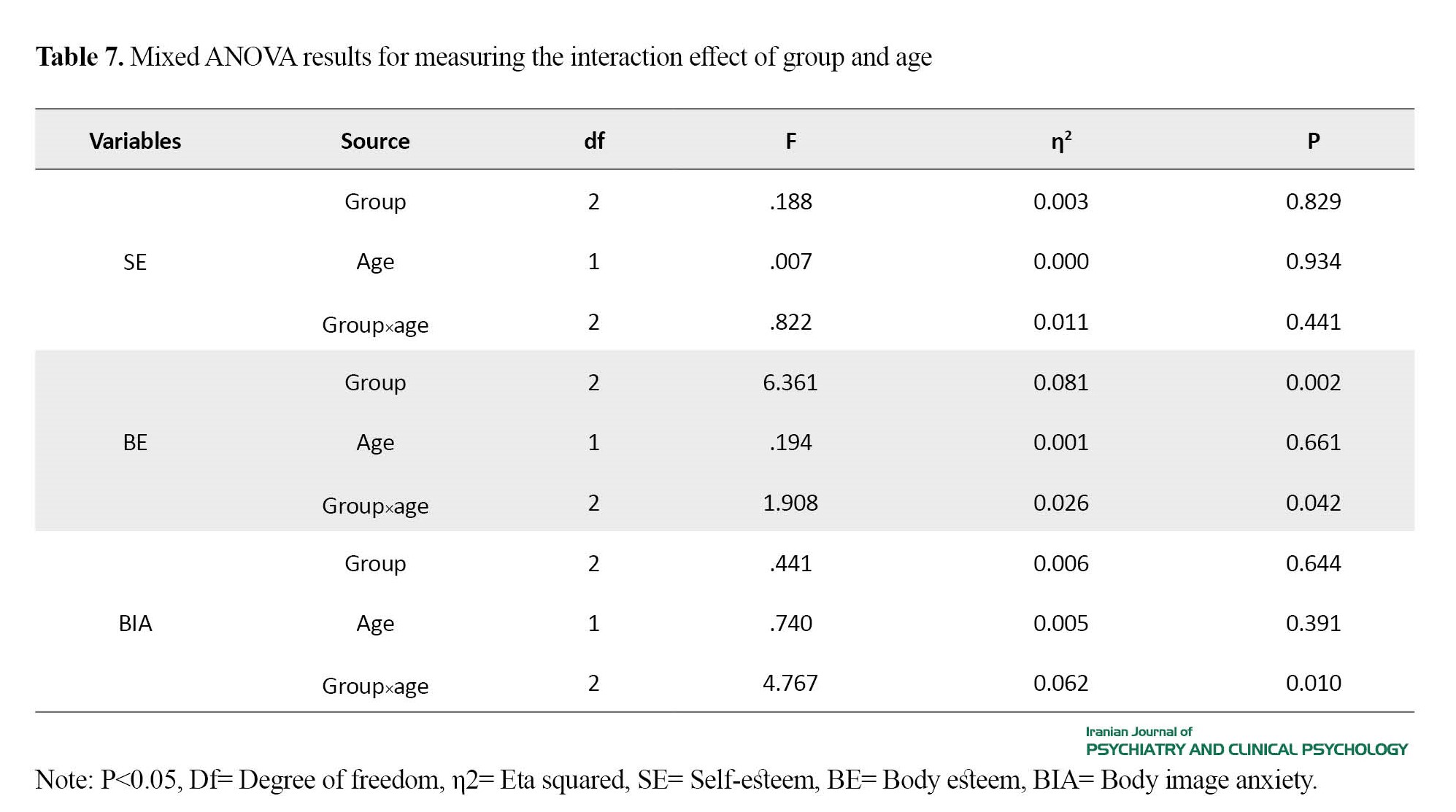

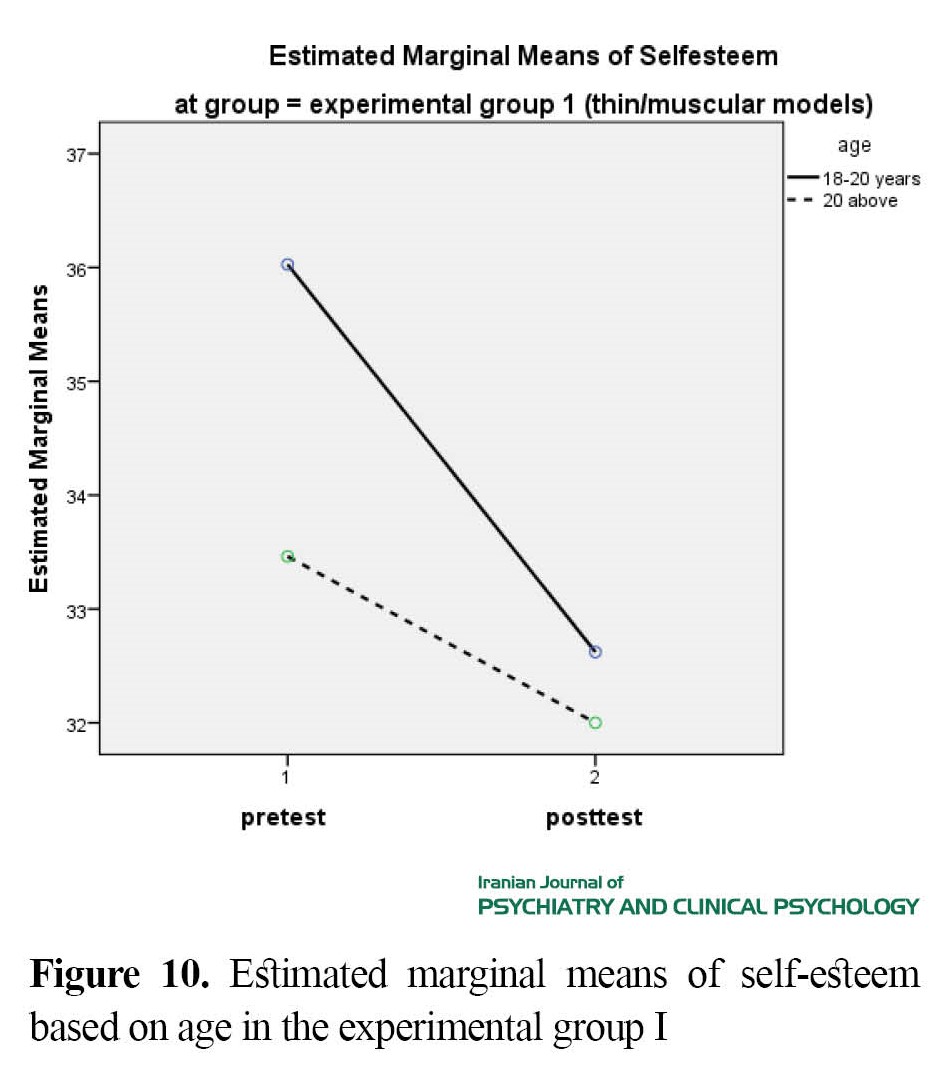

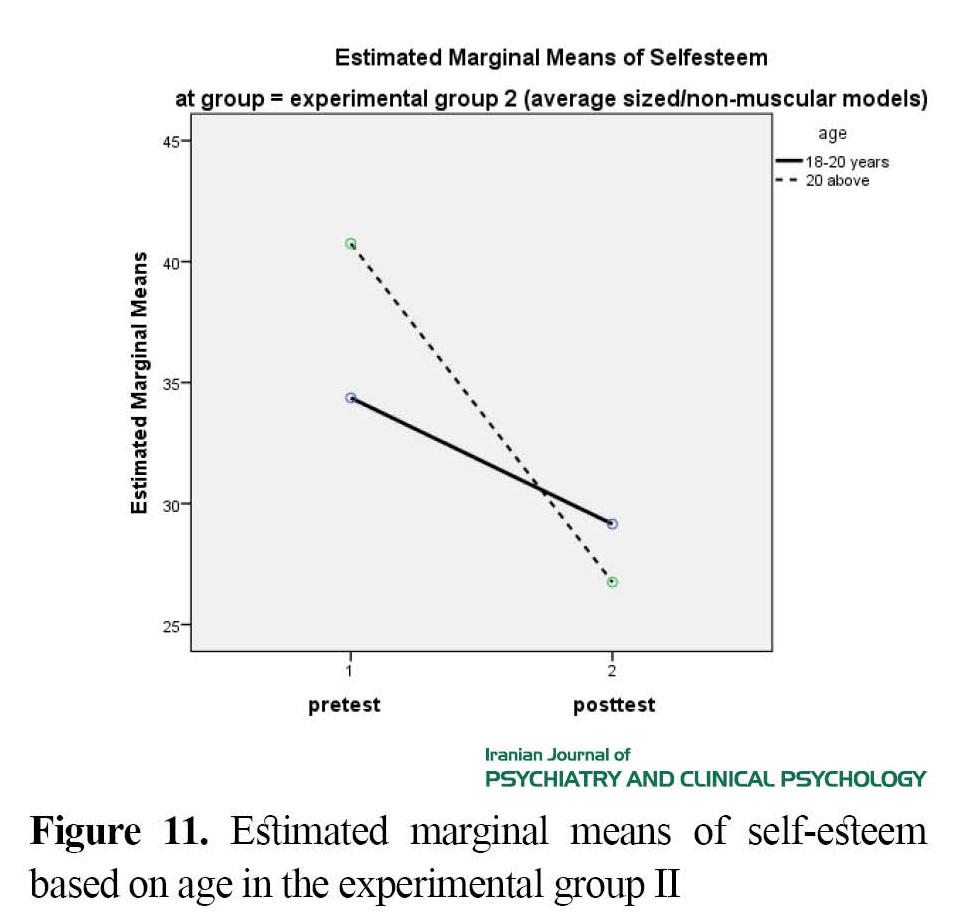

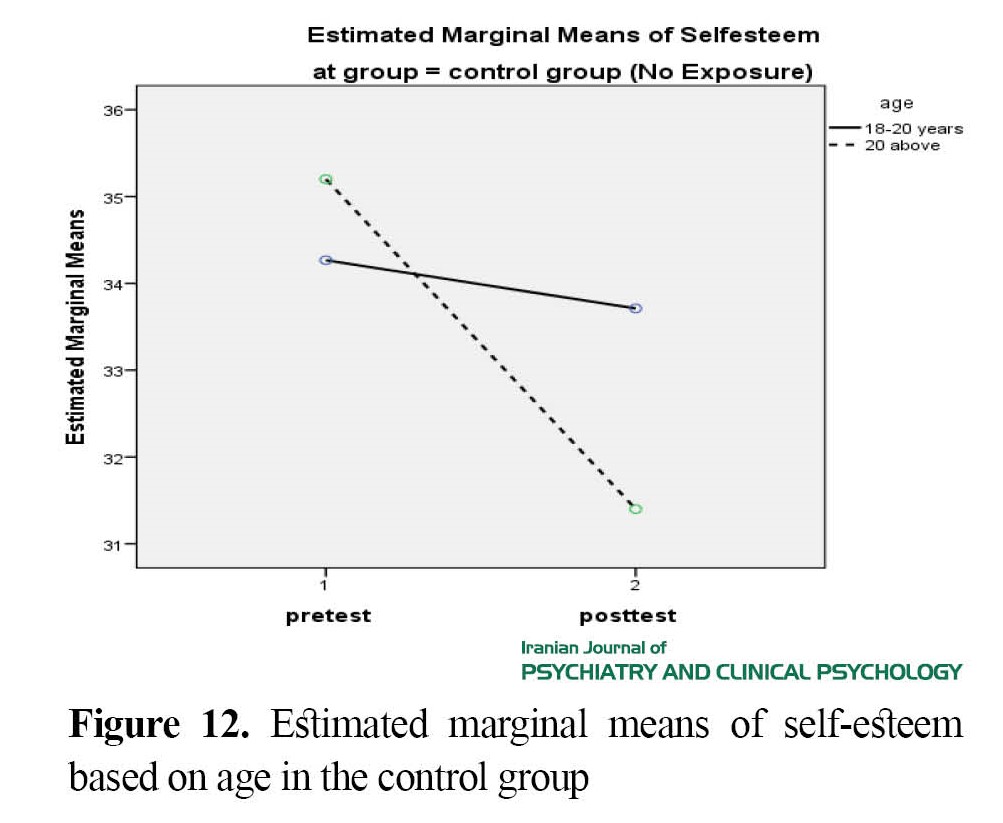

Figures 8 and 9 showed that female participants in all groups had high body image anxiety, but males had relatively low body image anxiety, indicating that male students suffer less from body image anxiety compared to female students. The results in Table 7 showed that the interaction effect of age and group on body esteem (F(2, 144) =1.908, P<0.042) and body image anxiety (F(2, 144)=4.767, P<0.010) was significant, but it was not significant on the self-esteem (F (2, 144)=9.306, P< 0.441). Figure 10 showed that participants from the age group 18-20 years in the experimental group I had high decrease in their self-esteem scores after exposure, while participants aged ≥20 years showed less changes in self-esteem after exposure. The scatter plot of self-esteem scores based on age in the experimental group II (Figure 11) showed that participants aged ≥20 years had lower levels of self-esteem in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase, while the scores of participants aged 18-20 years remained almost the same. Figure 12 showed that the participants aged ≥ 20 years in the control group had a decreased self-esteem, while the participants aged 18-20 years showed no condierable change in the self-esteem in the posttest phase. In overall, the participants aged 18-20 years who were exposed to the images of thin female or muscular male models, showed a declined self-esteem. However, in the experimental group II and control group, the participants aged ≥20 years showed a decreased self-esteem, and those aged 18-20 years did not showed a condierable change from pretest to posttest phases.

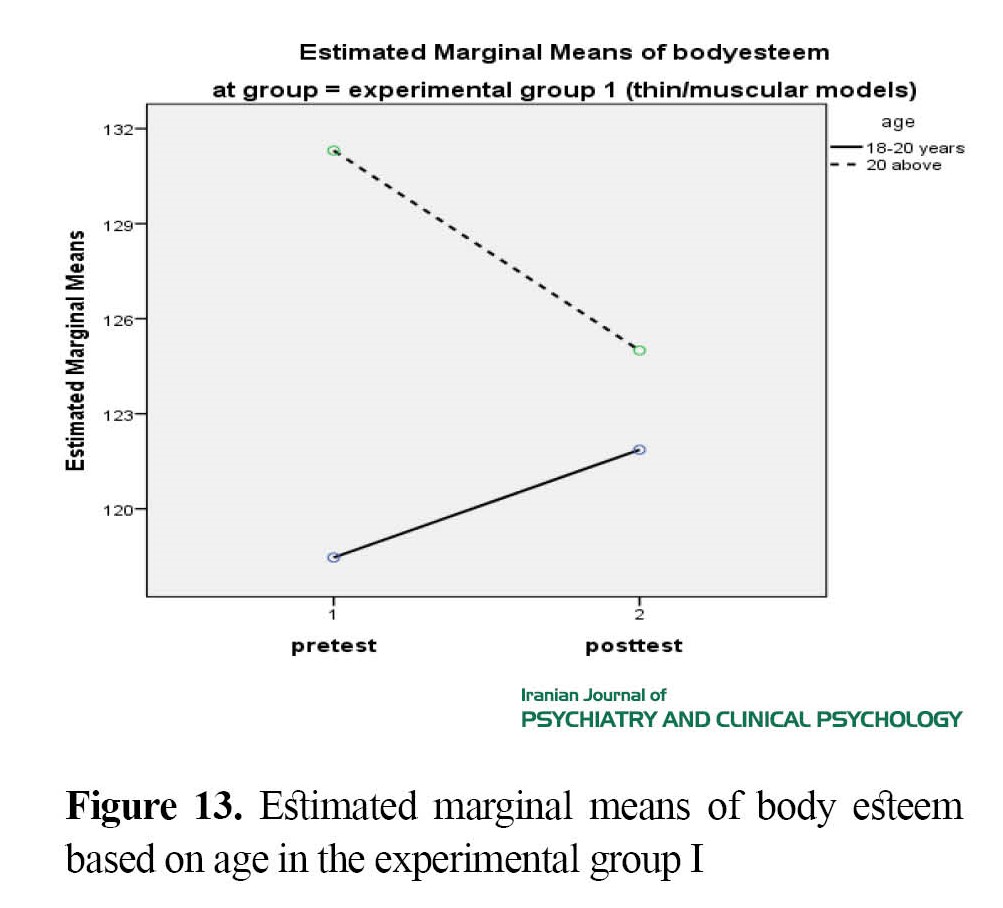

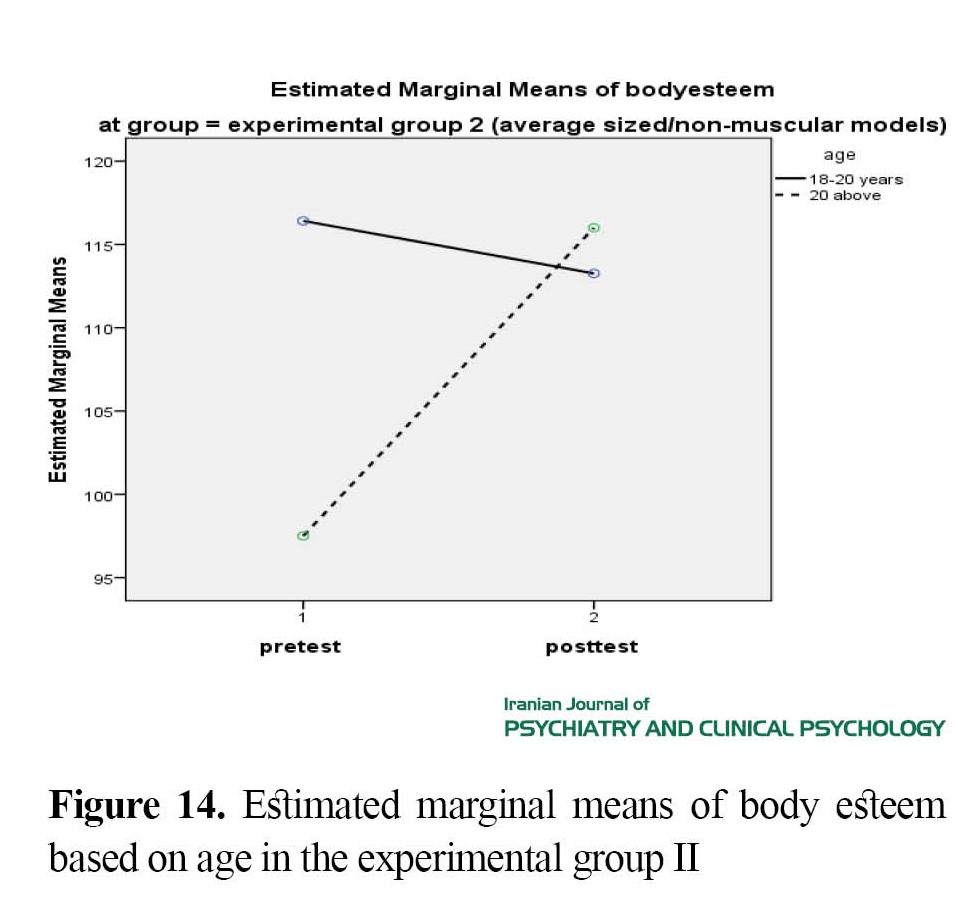

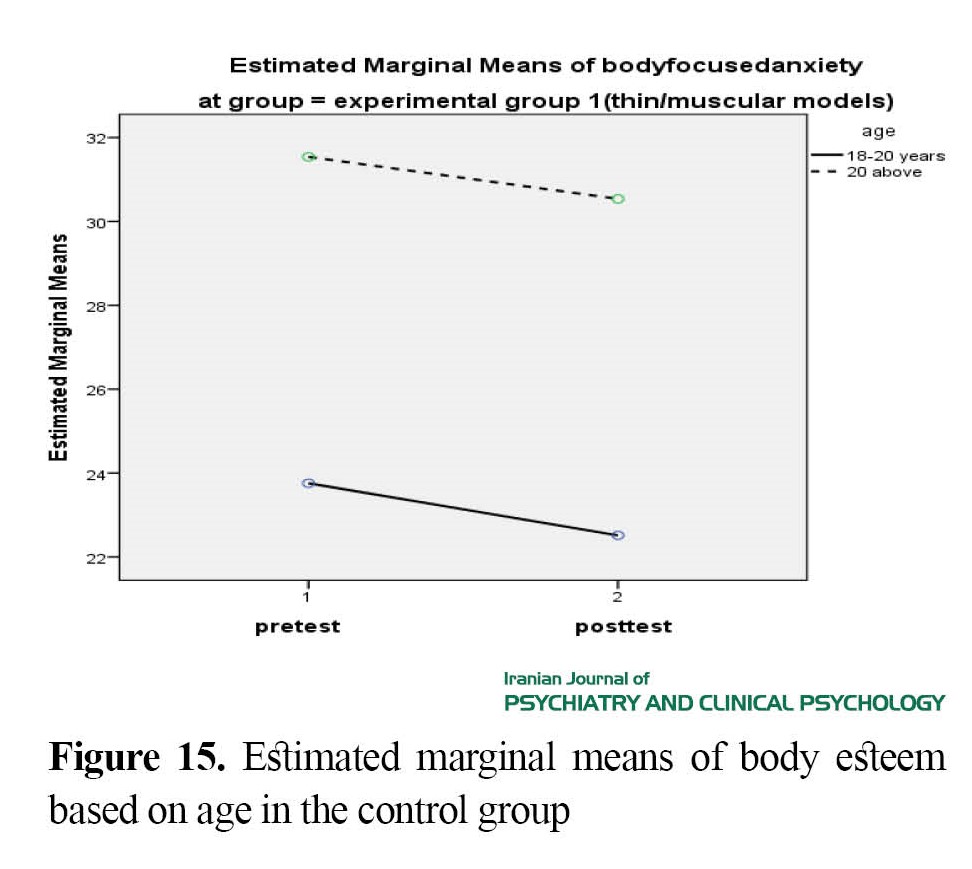

Figure 13 showed that the participants aged ≥20 years in the experimental group I had a decline in the body esteem in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase, while the body esteem of participants aged 18-20 years showed an increase in the posttest phase. According to Figure 14, in the experimental group II, the participants aged ≥20 years showed an increased body esteem in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase. However the body esteem of participants aged 18-20 years remained almost the same compared to the pretest phase.

Figure 15 showed that both age groups (18-20 years and ≥20 years) showed a highly decreased body esteem in the control group. Overall, the participants aged ≥20 years showed a significant decline in body esteem in the posttest phase, while the participants aged 18-20 years did not show any significant difference in body esteem in the pretest and posttest phases.

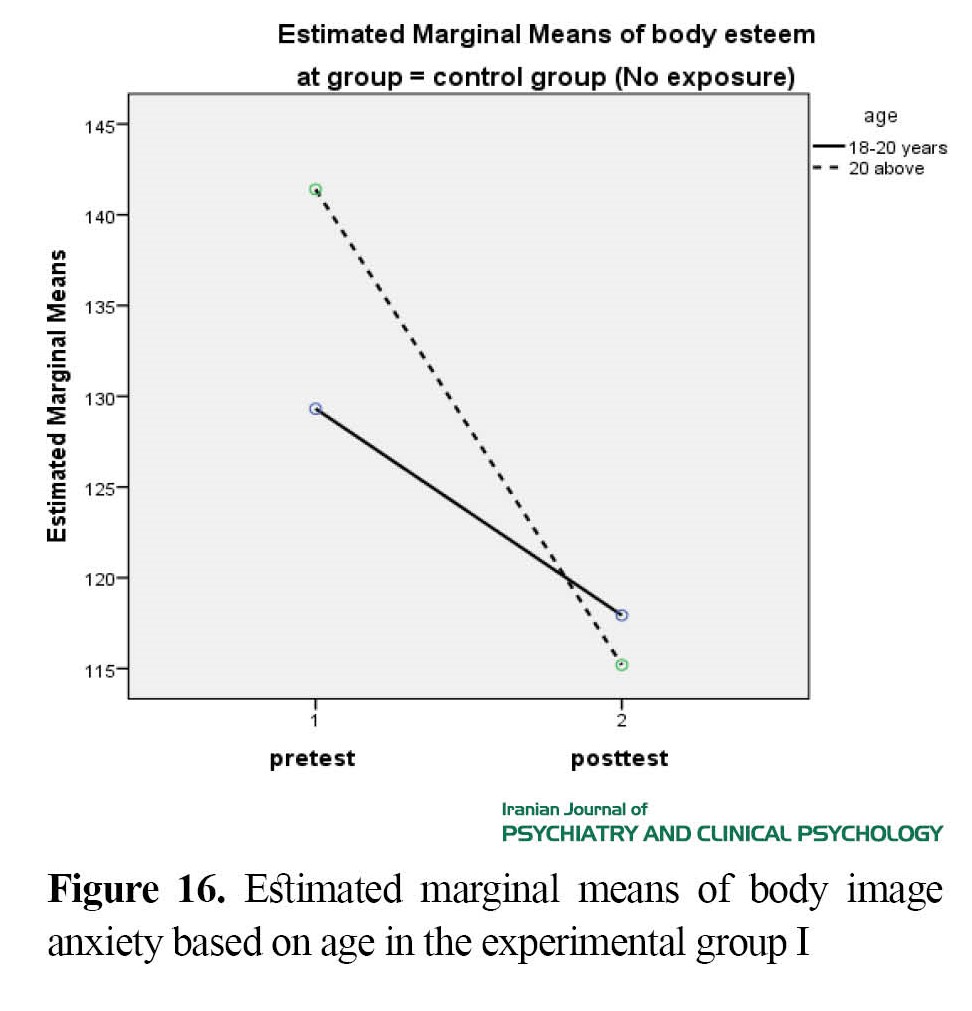

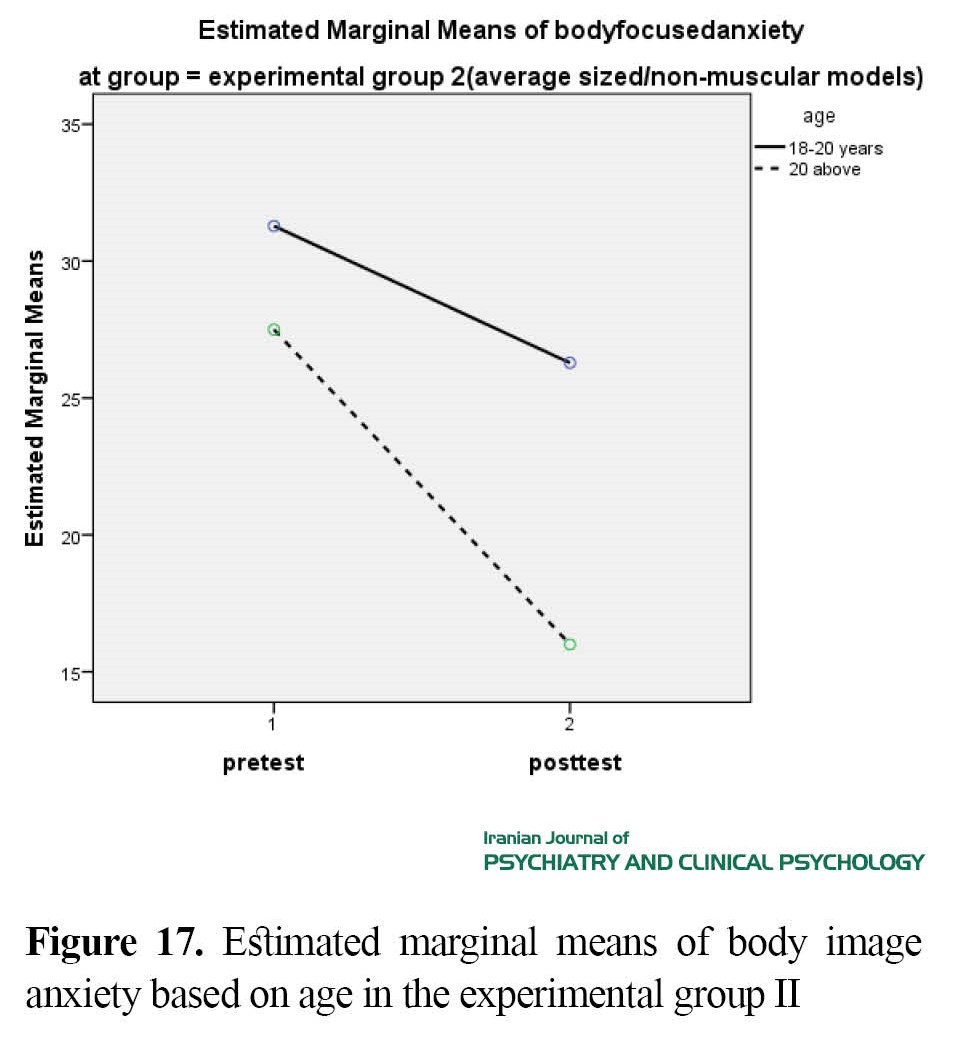

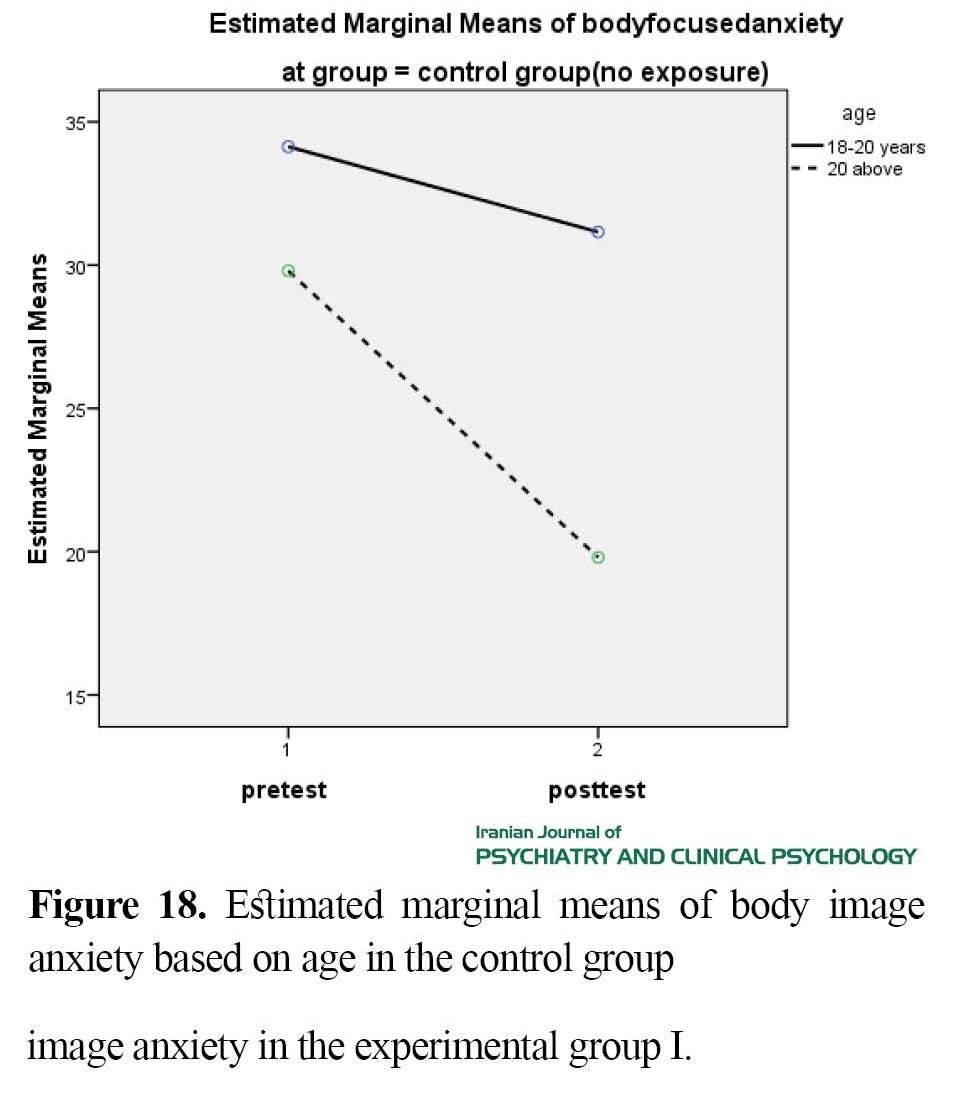

Figure 16 showed that both age groups had non-significant changes in the pretest and posttest scores of body image anxiety in the experimental group I. As illustrated in Figure 17, both age groups showed declined body image anxiety in the experimental group II. Figure 18 showed that, in control group, participants aged ≥20 years showed declined body image anxiety in the posttest phase, while the declined body image anxiety of participants aged 18-20 years remained almost unchanged. In overall, it can be said that age does not affect the body image anxiety of college students, because even after exposure to experimental conditions, they did not show any rise in body image anxiety; instead, their anxiety decreased in all three groups.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of social media images on self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety of college students (male and female) in Pakistan. The results of mixed ANOVA about the interaction effects of group and gender on the self-esteem of students indicated a significant impact. Male students in the experimental group I (exposed to the images of thin/muscular models), experimental group II (exposed to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models), and control group (no exposure) showed a low self-esteem than female students in the posttest phase. This rejects the assumption that females have lower self-esteem. Low self-esteem is mostly seen in women rather than in men [44], but the results of the present study showed the higher negative effects of exposure to ideal media models in men. It can be justified by the fact that the drive for muscularity in men specifically in Pakistan may be higher and they internalize the ideal media images which leads to low self-esteem. There is also evidence that men experience low self-esteem when exposed to the images of ideal male bodies [45, 46]. However, the first hypothesis of this study stating that students in the experimental group I have low self-esteem compared to the students in the experimental group II was confirmed. Literature supports the fact that people who are exposed to ideal bodies have lower self-esteem compared to people who are exposed to moderate body types [47]. The estimated marginal means of body esteem indicated that, in the experimental group I, the body esteem of female students highly declined after exposure, where the scores was higher in males. Previous research supports the result that men are less focused on ideal body [48]. In the experimental group II, body esteem of students remained almost unchanged from pretest to posttest. A study [43] also showed no effect of media images on the body esteem of the group exposed to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models. Female students in all three groups had high body image anxiety, while males had relatively low anxiety, indicating that males suffer less from body image anxiety compared to their female counterparts. This suggests that female students are more sensitive to their appearances which can be the reason for their high body image anxiety. Hence the findings of present study confirmed that male students show low levels of body image anxiety. Literature suggest that body image anxiety is prevalent among women in both western and eastern societies. Females’ concerns about weight and body image has reached a peak level such that it has become a normal part of their experiences [49].

The results of mixed ANOVA about the interaction effects of group and age on the self-esteem showed that students aged 18-20 years in the experimental group I showed a high decrease after exposure to media images; however, the score of students aged ≥20 years showed less change with non-significant difference compared to the pretest scores. In the experimental group II, the students aged ≥20 years scored relatively low after exposure to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models compared to their pretest scores. However, the participants with both age ranges in the control group had non-significant differences in self-esteem. The result of a study suggested that individuals’ perception of ideal body is changed over time; at young age, individuals feel that they are similar to the idealized media images, while in the mid-twenties, they feel less similar to them and experience low self-esteem [6, 38, 50]. Estimated marginal means indicated that students at the age of ≥20 years in the experimental group I had a decline in body esteem, while the body esteem of students aged 18-20 years increased. In the experimental group II, the students aged ≥20 years showed a higher body esteem in the posttest phase than in the pretest phase, while the body esteem of students aged 18-20 years remained almost unchanged. Both age groups (18-20 and ≥20 years) in the control group showed a decreased body esteem. It suggests that college students feel worse about their bodies such that they have low body esteem; the exposure to the images of models with a body shape similar to theirs did not provoke body esteem worries [19, 50, 51]. The students aged ≥20 years had more body image anxiety in all three groups compared to the stduents aged 18-20 years. People in their twenties usually suffer from body image anxiety as they think that they are getting old and they will not be young again [38].

Conclusion

In a developing country like Pakistan, exposure to ideal media images has a signifcant negative effect on self-esteem and body esteem of college students which leads to their body image anxiety.

Low self-esteem after exposure to media images seems to be more prevalent in male students that in females. On the contrary, females have lower body esteem. Further studies are needed in other parts of Pakistan and in other developing countries on the effects of media images on college students.

Limitations of the study

Despite the usefulness of the current study, it had some limitations. The first limitation was that samples were only from the government colleges; if there were also students from private colleges, a comparative study could provide detailed information about the differences in the study variables between the students form the government and private colleges. Second limitation was that we used the images of foreign models for stimulation; the use of images from local models could lead to different outcome. Another limitation was that, samples were mostly from the same ethnic groups; the use of samples from different ethnic groups could information about the differences in the studied variables based on ethnic differences.

Implications

The findings from the study highlight the different effects of exposure to media images between male and female college students. This study can be helpful for increasing the knowledge of media based on intervention programs. These programs can encourage both male and female college students to be more aware of the effcet of media images. The results of the study can also be useful for counselors; new counseling techniques can be used to help young students with low self-esteem and body esteem. The results also have implications for health and nutritional experts; new treatment plans and dietery regimen can be provided for students suffering from image anxiety.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethical Guidelines.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Maria Muzaffar Janjua and Anila Kamal; Investigation and resources: Maria Muzaffar Janjua and Ayesha Khan; Writing – Original Draft: Maria Muzaffar Janjua; Writing – Review & Editing: Ayesha Khan and Anila Kamal; Supervision: Anila Kamal.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all students participated in the study for their coperation.

References

The emergence and growth of social networking sites around the world began in the early 21st century. Since then, these sites have become an integral part of many people’s lives, particularly for young people. Many adults use social media applications, particularly Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram to make friends or connect with others around the world, share or learn new things, develop stronger personalities, and improve appearance and life style [1]. The body positivity media campaigns can increase the acceptance of different body sizes. Thin ideal promoting media campaign increases dislike of heavier individuals. One study claimed that self-esteem of people is enhanced after watching realistic body images in media.

Since social media has a long-lasting impact on people’s lives, it may have long-term consequences for them, but there is scant research on its mechanism. Studies have shown that social media plays a key role in women’s negative thoughts about their bodies. Social media propagates the socio-cultural ideals about ideal body shape and size, resulting in different perception of an ideal body by men and women [2]. The recent coronavirus pandemic and related lockdown has had an impact on social media use, which may be a reason for increased desire for being thin or the risk of eating disorders among adolescent and young women [3]. There has been increasing debates on whether the way social media show ideal body types is a risk factor for negative body image in both men and women, particularly in women. Body image has turned into a significant factor in one’s mental health, self-esteem, and well-being due to the increased use of social media. In western countries as well as eastern countries, the unrealistic body images are shown daily in newspapers, TV commercials, movies, and social media; these images affect the self-esteem and body image of men and women [4].

The users may upload contents in online social media to be seen by others. It is important to assess how users perceive their presence in social media. High social media use (for both posting and viewing contents) is related to lower body image satisfaction and self-esteem [5, 6]. Several studies have found that social media use is related to body esteem concerns among young adults [7, 8]. Social media show idealized images of men and women. Many of these images tend to determine specific ideals as beautiful. Thinness is emphasized for females and muscularity is emphasized for males [9]. Media users compare their bodies with these images [10]. When young adults are exposed to these media images and consider them as social norms, they start to be like them.

Pakistan is a country, where many problems and issues are health related. In spite of poverty and malnutrition, many females are unexpectedly more concerned and obsessed with their looks and physical appearance and at times this too much concentration can lead to body focused anxiety among females [11]. Pakistani fashion industry has grown enormously with modeling careers (and very thin models) becoming more visible in print and electronic media [12]. Present study aims to be the first to look at the effect media has on the self-esteem, body esteem and body focused anxiety of college students in a conservative, developing country like Pakistan.

There are different opinions about whether social media creates new fashions in a society or just reveals the existing fashions. It is suggested that people (men and women) with low body esteem are more likely to compare themselves with physically attractive people than those with high body esteem [13]. A study showed that women exposed to attractive images on social media are more likely to define themselves and their self-worth based on physical appearance [14]. Physical appearance has been as one of the predictors of self-esteem at many ages, indicating that self-esteem is linked to feelings and thoughts about body [15]. Research points out that self-esteem and body esteem are strongly related to each other among almost all young adults [16]. A meta-analysis study [17] reported that women and men of all age groups in different countries are affected by thin- and muscular-ideal internalization. The society in Pakistan, like other countries, pays more attention to the attractiveness of women and, therefore, women have worries about being rejected based on their appearance most of the time [18]. Pakistani fashion industry has had enormous growth with different types of modeling careers, where very thin models are shown in print and online media [12]. A study in Pakistan showed a significant positive relationship between body image and self-esteem in college students but the difference in terms of gender was not reported significant [12]. Results of another study indicated that women in middle age or older age are less concerned about their body image [19]. Men with low body esteem have less satisfaction when they compare their own pictures with the pictures of men with ideal body type [20]. Social media has become popular among young adults; therefore, its excessive use may cause adverse behaviors among them [21].

Body image anxiety or body image dissatisfaction, refers to one’s dissatisfaction with body image and physical appearance [22]. Low body esteem in young adults often leads to experiencing body image anxiety, Research suggests that high exposure to the media may be associated with body image anxiety in young men and women [23]. Mass Media often provide information about idea physical appearance like slim body for women and muscular male body which leads to internalized ideal body standard propagated by media [7, 24].

Media can develop many disorders related to body image, size, and appearance which in turn can lead to low body satisfaction and produce a gap between ideal and actual body image [25, 7, 26]. The more one reads or watches something related to the appearance, the more psychological pressure and negative body image s/he will have, which leads to body image anxiety [27, 28]. Furthermore, those who follow the celebrities on social media are more likely to have depressive symptoms and body image anxiety [15]. Females are more likely to reduce their weight after exposure to social media images of thin models and being criticized by parents, relatives, and friends [29]. The findings of a recent study in Pakistan reported the impact of family pressure, peer pressure and media pressure on body image dissatisfaction among female workers [30]. Parents’ pressure verbally or by active encouragement has been shown to have more impact on their children’s (at any age) body image concerns than the social media models. Both mothers and fathers are key sources of influence on the children’s body image [31], in addition to the media [32]. Results of a study indicated that parents’ educational level and family type (joint or nuclear) affect the body esteem and body image in children [33].

Another influencing socio-cultural factor of body image anxiety is the socioeconomic status. Previously, it is believed that body image anxiety is more prevalent among young adults from upper-class communities, but few studies have claimed that body image anxiety is not limited to people from upper class and people belonging to lower class can also have body image anxiety [34]. Despite poverty and malnutrition, many women are concerned about their physical appearance which can lead to body image anxiety among them. In Pakistan, government-owned institutions are Urdu medium and traditional, and use English as a separate medium, while private institutions are English medium and mostly follow the traditions of Western countries in education and ruling. These two types of institutions reflect differences in the socio-economic level of students in Pakistan, where the former represents the lower-class communities and the latter represents the upper-class communities. Students from the English-medium institutions have greater body image anxiety than the students from Urdu-medium institutions [35].

Although many studies have investigated the effects of social media on body esteem and body image dissatisfaction of women, very few studies have investigated the extent of its effect on the body image of men, especially male college students in Pakistan. Therefore, there is a need to investigate how the body image of male college students in Pakistan is affected by exposure to images represented on social media as ideal. Present study will also investigate the difference among individuals’ perceptions about study variables belonging to different family systems. It is assumed that desired results will be founded from present research as the literature strongly supports the proposed model.

Study objectives and hypotheses

The present study aims to investigate the effects of social media on male and female college students’ self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety and examine the gender differences. The study hypotheses are formulated as follows:

• Students with exposure to the images of thin/muscular models have lower levels of self-esteem than those with exposure to middle-sized/non-muscular model images.

• Students with exposure to the images of thin/muscular models have lower levels of body esteem than those with exposure to middle-sized/non-muscular model images.

• Students with exposure to the images of thin/muscular models have higher levels of body image anxiety than those with exposure to middle-sized/non-muscular model images.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is an experimental study with a pretest/posttest design. A mixed factorial design was used in order to minimize the limitations. Therefore, within -group and between-group designs (randomized, matched and factorial) were used. The overall design was as: 2 (Phases: pretest and posttest) × 3 (Conditions: exposure to the images of thin models, exposure to the images of middle-sized models, and no exposure) × 2 (Gender: male and female). The independent variable was the exposure to images of models.

Sample was selected by a purposive sampling method from college students of governmental model colleges for boys and girls in Islamabad, Pakistan (N=150, 75 females and 75 males, aged 18-25 years) (Figure 1). College students was targeted as the study population because literature suggests that young adults are more concerned about their appearances and suffer more from body image anxiety compared to children and adults [36, 37, 38]. Initially data was collected from 40 individuals per group. After removing the questionnaires with missing data, 25 samples in each group remained. In experimental studies, the researcher needs to control all the variances; hence, a small sample size is better for effective manipulation [39]. Using the G*Power software, version 3, the sample size was obtained 25 for each group. Inclusion criteria were: a moderate body mass index (BMI=20-24.99 Kg/m2) [40, 41], being a student in Government model Colleges, and age 18-25 years. Exclusion criteria were: A BMI below or above average, being a student from private colleges, and age <18 or >25 years.

Samples were randomly assigned to three groups with equal number of individuals: (1) Group I: females exposed to the images of slim/thin female models and males exposed to the images of muscular male models, (2) Group II: females exposed to the images of middle-sized female models and males exposed to the images of non-muscular male models, (3) Control group: not exposed to the images of any models. At the pretest phase, they completed self-report questionnaires to measure their self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety. At the posttest phase, a three-week interval was used to avoid the effect of changes in performance due to practice or fatigue. Then, the two experimental groups exposed to the images on social media and then were asked to fill the self-report questionnaires once again. The control group completed the questionnaires without exposure to any images on social media.

Instruments

Following instruments were used in the present study.

State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES)

It has 20 items and three subscales: Performance Self-Esteem (7 items), Social Self-Esteem (7 items) and Appearance Self-Esteem (6 items). Only Social Self-Esteem and Appearance Self-Esteem subscales (13 items) were used in the present study. Performance Self-Esteem Subscale was excluded as it was not related to the study objectives. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale as 1= Not at all, 2= A little bit, 3= Somewhat, 4=Very Much and 5= Extremely). Some items have reversed scoring (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10 and 13 in the current study). The reliability of the overall scale is α=0.92, and the reliability of performance, social and appearance subscales are 0.64, 0.60 and 0.55, respectively.

The Body Esteem Scale (TBES)

It has 35 items and three subscales for males and three subscales for females. Subscales for males are physical attractiveness (11 items), upper body strength (9 items) and physical condition (13 items). Subscales for female are sexual attractiveness (13 items), weight concern (10 items), and physical condition (9 items). The items are scored on a 5-point scale as 1= Strong negative feelings, 2= Moderate negative feelings, 3= No feeling one way or the other, 4= Moderate positive feelings, and 5= Strong positive feelings. Higher scores indicate more favorable body esteem, while lower scores indicate less favorable body esteems. The reliability of TBES ranged 0.78-0.87.

Physical Appearance State and Traits Anxiety Scale (PASTAS) [42]: It has two versions, the Trait Version and the State Version. In present study, the State version was used which has 16 items scored on a 5-point scale as 1= Not at All, 2= Slightly, 3= Moderately, 4= Very much so, and 5= Exceptionally so. The reliability of PASTAS ranged 0.82-0.92. High scores indicate high level of anxiety and tension about body.

After obtaining informed consent from the participants, they were invited to complete the questionnaires in three different classrooms. In each classroom, there were two researchers as instructors. After completion of the questionnaires, the participants were informed that they need to complete the questionnaires again after 3 weeks.

Stimulation

After three weeks, the participants were exposed to the experimental stimuli in the lab. Participants were exposed to the images using multimedia projectors. Each image was displayed for 45 seconds because the researcher wanted to record the state condition of participants. For female participants,fiveprint images of thin and middle-sized female models were used for the stimulation. Images were edited in Photoshop to make thin models look middle-sized. Female respondents were asked two questions about each five images according to the method proposed in a previous study [43]. The first question was: “Please rate the attractiveness of the model in the image”. Responses were based on a 7-point scale ranged from 1= Very unattractive to 7=very attractive. The second question was: “How do you perceive the size of the model in the image? Responses were recorded based on a 7-point scale ranged from 1=Very thin to 7= Very thick”.

For the stimulation of male participants, five print images of muscular/non-muscular models were used. Images were edited in Photoshop to make non-muscular models to look muscular. They were asked two questions about each five images. The first question was: “Please rate the attractiveness of the model in the image”. Responses were based on a 7-point scale from 1= Very unattractive to 7= Very attractive. Second question was: “How do you perceive the size of the model in the image?” Responses were based on a 7-point scale from 1= Very lean to 7= Very muscular.

It was kept confidential that what type of exposure they were given. Participants in the control group did not receive any kind of experimental manipulation and were not informed about the treatment given to other two groups. After experimental manipulation in the experimental groups, participants of all groups including control group were asked complete the three questionnaires.

Data analysis

For comparing the different groups, the 2×3×2 mixed factorial design was used. Along with descriptive statistics, independent t-test was used to examine the gender differences. Mixed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the differences among experimental conditions. In checking the normality of data distribution, the values of skewness and kurtosis were within normal range and the scores of all questionairs were normally distributed.

Results

There were 50 participants in each group (25 males and 25 females). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of participants using frequency and percentage.

As can be seen, the educational level of the parents of students was at moderate level. Moreover, 85% of participants had an age of 18-20 years, 50% had 1-3 siblings, and 82% were from nuclear families.

Internal consistency of the questionnaires

Internal consistency of the Pakistani version of three questionnaires was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. As can be seen in Table 2, the Cronbach’s alpha values of TBES and PASTAS were very high, indicating that they had high internal consistency.

For the SSES and its subscales, the results indicated the moderate internal consistency in both pretest and posttest phases. The upper body strength subscale for males and sexual attractiveness subscale for females in TBES showed a decline in the posttest phase, indicating that it is affected by the experimental treatment.

Examining gender differences

To examine gender differences in terms of the study variables, independent t-test was conducted. Table 3 represents the mean scores of three variables (Self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety) for male and female samples.

The results indicated a statistically significant difference between males and females in both pretest and posttest phases.

Examining differences based on the family type

For examining the differences based on the family type (joint and nuclear) in the study variables, independent t-test was conducted. A statistically significant difference between the two types of families were found in terms of the study variables in both pretest and posttest phases (Table 4).

It indicates the significant change after exposure to the images.

Examining differences based on age

Independent t-test was used to eaxamine the differences in the study variables based on age (18-20 and ≥20 years) in the pretest and posttest phases. The results in Table 5 showed a significant difference between the two age groups.

It indicates the significant changes in scores after exposure to the images.

Effects of group, gender, and age on the study variables

Mixed ANOVA was used to examine the effects of group, gender, and age on the study variables (self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety). The results in Table 6 indicated the statistically significant interaction effect of gender and group on the self-esteem (F(2,144)=3.676, P<0.028).

Regarding the body esteem, the interaction effect of gender and group was also significant (F(2,144)=7.119, P<0.000). The results in Table 6 indicated that interaction effect of gender and group on body image anxiety was also significant (F (2, 144) = 9.306, P<00).

Figure 2 showed that the self-esteem of male students was highly declined in the posttest phase in the experimental group I where they were exposed to the images of muscular male models. Compared to male students, females showed less difference in the self-esteem from the pretest to posttest phases.

Figure 3 showed that male participants had relatively low self-esteem in the experimental group II where they were exposed to the images of non-muscular male models. However, the self-esteem of female participants remained relatively stable after being exposed to the images of middle-sized models.

Figure 4 showed that, in the control goup, the level of self-esteem increased in female participants and decreased in male participants in the posttest phase. In overall, it can be concluded that the self-esteem of students (both males and females) in the experimental group I were significantly decreased after exposure. However, the change in the scores of male participants was significantly higher compared to female participants.

In Figure 5, the scatter plot showed that the body esteem of female participants in the experimental group I decreased after exposure to the images of middle-sized female models, while the scores of male participants increased after exposure to the images of non-muscular models. Figure 6 showed that body esteem remained almost the much same for both male and female participants in experimental group II (exposed to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models). Figure 7 showed that male participants in the control group showed a decreased body esteem, while female participants’ body esteem remained almost unchanged. In overall, the body esteem of female participants in all groups remained stable, but male participants in the experimental group II (exposure to the images of middle-sized/ non-muscular models) and control group (no exposure) showed a high decrease in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase.

Figures 8 and 9 showed that female participants in all groups had high body image anxiety, but males had relatively low body image anxiety, indicating that male students suffer less from body image anxiety compared to female students. The results in Table 7 showed that the interaction effect of age and group on body esteem (F(2, 144) =1.908, P<0.042) and body image anxiety (F(2, 144)=4.767, P<0.010) was significant, but it was not significant on the self-esteem (F (2, 144)=9.306, P< 0.441). Figure 10 showed that participants from the age group 18-20 years in the experimental group I had high decrease in their self-esteem scores after exposure, while participants aged ≥20 years showed less changes in self-esteem after exposure. The scatter plot of self-esteem scores based on age in the experimental group II (Figure 11) showed that participants aged ≥20 years had lower levels of self-esteem in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase, while the scores of participants aged 18-20 years remained almost the same. Figure 12 showed that the participants aged ≥ 20 years in the control group had a decreased self-esteem, while the participants aged 18-20 years showed no condierable change in the self-esteem in the posttest phase. In overall, the participants aged 18-20 years who were exposed to the images of thin female or muscular male models, showed a declined self-esteem. However, in the experimental group II and control group, the participants aged ≥20 years showed a decreased self-esteem, and those aged 18-20 years did not showed a condierable change from pretest to posttest phases.

Figure 13 showed that the participants aged ≥20 years in the experimental group I had a decline in the body esteem in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase, while the body esteem of participants aged 18-20 years showed an increase in the posttest phase. According to Figure 14, in the experimental group II, the participants aged ≥20 years showed an increased body esteem in the posttest phase compared to the pretest phase. However the body esteem of participants aged 18-20 years remained almost the same compared to the pretest phase.

Figure 15 showed that both age groups (18-20 years and ≥20 years) showed a highly decreased body esteem in the control group. Overall, the participants aged ≥20 years showed a significant decline in body esteem in the posttest phase, while the participants aged 18-20 years did not show any significant difference in body esteem in the pretest and posttest phases.

Figure 16 showed that both age groups had non-significant changes in the pretest and posttest scores of body image anxiety in the experimental group I. As illustrated in Figure 17, both age groups showed declined body image anxiety in the experimental group II. Figure 18 showed that, in control group, participants aged ≥20 years showed declined body image anxiety in the posttest phase, while the declined body image anxiety of participants aged 18-20 years remained almost unchanged. In overall, it can be said that age does not affect the body image anxiety of college students, because even after exposure to experimental conditions, they did not show any rise in body image anxiety; instead, their anxiety decreased in all three groups.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of social media images on self-esteem, body esteem, and body image anxiety of college students (male and female) in Pakistan. The results of mixed ANOVA about the interaction effects of group and gender on the self-esteem of students indicated a significant impact. Male students in the experimental group I (exposed to the images of thin/muscular models), experimental group II (exposed to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models), and control group (no exposure) showed a low self-esteem than female students in the posttest phase. This rejects the assumption that females have lower self-esteem. Low self-esteem is mostly seen in women rather than in men [44], but the results of the present study showed the higher negative effects of exposure to ideal media models in men. It can be justified by the fact that the drive for muscularity in men specifically in Pakistan may be higher and they internalize the ideal media images which leads to low self-esteem. There is also evidence that men experience low self-esteem when exposed to the images of ideal male bodies [45, 46]. However, the first hypothesis of this study stating that students in the experimental group I have low self-esteem compared to the students in the experimental group II was confirmed. Literature supports the fact that people who are exposed to ideal bodies have lower self-esteem compared to people who are exposed to moderate body types [47]. The estimated marginal means of body esteem indicated that, in the experimental group I, the body esteem of female students highly declined after exposure, where the scores was higher in males. Previous research supports the result that men are less focused on ideal body [48]. In the experimental group II, body esteem of students remained almost unchanged from pretest to posttest. A study [43] also showed no effect of media images on the body esteem of the group exposed to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models. Female students in all three groups had high body image anxiety, while males had relatively low anxiety, indicating that males suffer less from body image anxiety compared to their female counterparts. This suggests that female students are more sensitive to their appearances which can be the reason for their high body image anxiety. Hence the findings of present study confirmed that male students show low levels of body image anxiety. Literature suggest that body image anxiety is prevalent among women in both western and eastern societies. Females’ concerns about weight and body image has reached a peak level such that it has become a normal part of their experiences [49].

The results of mixed ANOVA about the interaction effects of group and age on the self-esteem showed that students aged 18-20 years in the experimental group I showed a high decrease after exposure to media images; however, the score of students aged ≥20 years showed less change with non-significant difference compared to the pretest scores. In the experimental group II, the students aged ≥20 years scored relatively low after exposure to the images of middle-sized/non-muscular models compared to their pretest scores. However, the participants with both age ranges in the control group had non-significant differences in self-esteem. The result of a study suggested that individuals’ perception of ideal body is changed over time; at young age, individuals feel that they are similar to the idealized media images, while in the mid-twenties, they feel less similar to them and experience low self-esteem [6, 38, 50]. Estimated marginal means indicated that students at the age of ≥20 years in the experimental group I had a decline in body esteem, while the body esteem of students aged 18-20 years increased. In the experimental group II, the students aged ≥20 years showed a higher body esteem in the posttest phase than in the pretest phase, while the body esteem of students aged 18-20 years remained almost unchanged. Both age groups (18-20 and ≥20 years) in the control group showed a decreased body esteem. It suggests that college students feel worse about their bodies such that they have low body esteem; the exposure to the images of models with a body shape similar to theirs did not provoke body esteem worries [19, 50, 51]. The students aged ≥20 years had more body image anxiety in all three groups compared to the stduents aged 18-20 years. People in their twenties usually suffer from body image anxiety as they think that they are getting old and they will not be young again [38].

Conclusion

In a developing country like Pakistan, exposure to ideal media images has a signifcant negative effect on self-esteem and body esteem of college students which leads to their body image anxiety.

Low self-esteem after exposure to media images seems to be more prevalent in male students that in females. On the contrary, females have lower body esteem. Further studies are needed in other parts of Pakistan and in other developing countries on the effects of media images on college students.

Limitations of the study

Despite the usefulness of the current study, it had some limitations. The first limitation was that samples were only from the government colleges; if there were also students from private colleges, a comparative study could provide detailed information about the differences in the study variables between the students form the government and private colleges. Second limitation was that we used the images of foreign models for stimulation; the use of images from local models could lead to different outcome. Another limitation was that, samples were mostly from the same ethnic groups; the use of samples from different ethnic groups could information about the differences in the studied variables based on ethnic differences.

Implications

The findings from the study highlight the different effects of exposure to media images between male and female college students. This study can be helpful for increasing the knowledge of media based on intervention programs. These programs can encourage both male and female college students to be more aware of the effcet of media images. The results of the study can also be useful for counselors; new counseling techniques can be used to help young students with low self-esteem and body esteem. The results also have implications for health and nutritional experts; new treatment plans and dietery regimen can be provided for students suffering from image anxiety.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethical Guidelines.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Maria Muzaffar Janjua and Anila Kamal; Investigation and resources: Maria Muzaffar Janjua and Ayesha Khan; Writing – Original Draft: Maria Muzaffar Janjua; Writing – Review & Editing: Ayesha Khan and Anila Kamal; Supervision: Anila Kamal.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all students participated in the study for their coperation.

References

- Branden N. The psychology of self-esteem. New York: Bantam; 1989. [Link]

- McCabe M, Ricciardelli L. Parent, peer and media influences on body image and strategies to both increase and decrease body size among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence. 2001; 36(142):225-40. [PMID]

- Williams CJ, Power KG, Millar HR, Freeman CP, Yellowlees A, Dowds T, et al. Comparison of eating disorders and other dietary/weight groups on measures of perceived control, assertiveness, self‐esteem, and self‐directed hostility. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993; 14(1):27-32. [PMID]

- Davies E, Furnham A. The dieting and body shape concerns oe adolescent females. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1986; 27(3):417-28. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb01843.x] [PMID]

- Hawkins N, Richards PS, Granley HM, Stein DM. The impact of exposure to the thin-ideal media image on women. Eating Disorders. 2004; 12(1):35-50. [DOI:10.1080/10640260490267751] [PMID]

- Thomas K, O’Bannon B. Cell phones in the classroom: Preservice teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education. 2013; 30(1):11-20. [DOI:10.1080/21532974.2013.10784721]

- Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta‐analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002; 31(1):1-16. [DOI:10.1002/eat.10005] [PMID]

- Grogan S. Promoting positive body image in males and females: Contemporary issues and future directions. Sex Roles. 2010; 63(9):757-65. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-010-9894-z]

- Loth KA, Watts AW, Van Den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D. Does body satisfaction help or harm overweight teens? A 10-year longitudinal study of the relationship between body satisfaction and body mass index. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015; 57(5):559-61. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Meeus A, Beullens K, Eggermont S. Like me (please?): Connecting online self-presentation to pre-and early adolescents’ self-esteem. New Media & Society. 2019; 21(11-12):2386-403. [DOI:10.1177/1461444819847447]

- Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Thombs BD. A test of the moderating role of importance of appearance in the relationship between perceived scar severity and body-esteem among adult burn survivors. Body Image. 2006; 3(2):101-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.01.003] [PMID]

- Oehlhof ME, Musher-Eizenman DR, Neufeld JM, Hauser JC. Self-objectification and ideal body shape for men and women. Body Image. 2009; 6(4):308-10. [PMID]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J, Schouten AP. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2006; 9(5):584-90. [PMID]

- Cash TF, Henry PE. Women’s body images: The results of a national survey in the USA. Sex Roles. 1995; 33(1):19-28. [Link]

- Ata RN, Ludden AB, Lally MM. The effects of gender and family, friend, and media influences on eating behaviors and body image during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007; 36(8):1024-37. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-006-9159-x]

- Mahmud N, Crittenden N. A comparative study of body image of Australian and Pakistani young females. British Journal of Psychology. 2007; 98(Pt 2):187-97. [PMID]

- Banfield SS, McCabe MP. An evaluation of the construct of body image. Adolescence. 2002; 37(146):373-93. [PMID]

- Lappalainen R, Tuomisto MT, Giachetti I, D'Amicis A, Paquet S. Recent body-weight changes and weight loss practices in the European :union:. Public Health Nutrition. 1999; 2(1A):135-41. [PMID]

- Irving LM. Mirror images: Effects of the standard of beauty on the self-and body-esteem of women exhibiting varying levels of bulimic symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990; 9(2):230. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.230]

- Hawes T, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Campbell SM. Unique associations of social media use and online appearance preoccupation with depression, anxiety, and appearance rejection sensitivity. Body Image. 2020; 33:66-76. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.010] [PMID]

- Vall-Roqué H, Andrés A, Saldaña C. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on social network sites use, body image disturbances and self-esteem among adolescent and young women. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2021; 110:110293. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Halliwell E, Dittmar H. A qualitative investigation of women’s and men’s body image concerns and their attitudes toward aging. Sex Roles. 2003; 49(11):675-84. [DOI:10.1023/B:SERS.0000003137.71080.97]

- Agliata D, Tantleff-Dunn S. The impact of media exposure on males’body image. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005; 23(1):7-22. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.23.1.7.26988]

- Heatherton TF, Polivy J. Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social psychology. 1991; 60(6):895-910. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.895]

- Franzoi SL, Shields SA. The Body Esteem Scale: Multidimensional structure and sex differences in a college population. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1984; 48(2):173-8. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa4802_12] [PMID]

- Smolak L. Body image in children and adolescents: Where do we go from here? Body Image. 2004; 1(1):15-28. [DOI:10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00008-1] [PMID]

- Hausenblas HA, Janelle CM, Gardner RE, Hagan AL. Effects of exposure to physique slides on the emotional responses of men and women. Sex Roles. 2002; 47(11):569-75. [DOI:10.1023/A:1022030006663]

- Schur EA, Sanders M, Steiner H. Body dissatisfaction and dieting in young children. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000; 27(1):74-82. [PMID]

- McCreary DR, Sasse DK. An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health. 2000; 48(6):297-304. [DOI:10.1080/07448480009596271] [PMID]

- Akbar M, Nasir F, Aslam M, Qasim I. Effect of family pressure, peer pressure, and media pressure on body image dissatisfaction among women. Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies. 2022; 8(2):325-30. [DOI:10.26710/jbsee.v8i2.2249]

- Richins ML. Social comparison and the idealized images of advertising. Journal of Consumer Research. 1991; 18(1):71-83. [DOI:10.1086/209242]

- Rühl I, Legenbauer T, Hiller W. The impact of exposure to images of ideally thin models in TV commercials on eating behavior: an experimental study with women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa. Body Image. 2011; 8(4):349-56. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.07.002] [PMID]

- Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP, Banfield S. Body image and body change methods in adolescent boys: Role of parents, friends and the media. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000; 49(3):189-97. [PMID]

- Yamamiya Y, Cash TF, Melnyk SE, Posavac HD, Posavac SS. Women’s exposure to thin-and-beautiful media images: Body image effects of media-ideal internalization and impact-reduction interventions. Body Image. 2005; 2(1):74-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.11.001] [PMID]

- Martin MC, Kennedy PF. Advertising and social comparison: Consequences for female preadolescents and adolescents. Psychology & Marketing. 1993; 10(6):513-30. [DOI:10.1002/mar.4220100605]

- Durkin SJ, Paxton SJ. Predictors of vulnerability to reduced body image satisfaction and psychological wellbeing in response to exposure to idealized female media images in adolescent girls. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002; 53(5):995-1005. [PMID]

- Khan AN, Khalid S, Khan HI, Jabeen M. Impact of today’s media on university student’s body image in Pakistan: A conservative, developing country’s perspective. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:379. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-11-379] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Trampe D, Stapel DA, Siero FW. On models and vases: body dissatisfaction and proneness to social comparison effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007; 92(1):106-18. [PMID]

- Smeets E, Jansen A, Vossen E, Ruf L, Roefs A. Feeling body dissatisfied after viewing thin-ideal pictures is mediated by self-activation. Body Image. 2010; 7(4):335-40. [PMID]

- Abideen ZUI, Latif A, Khan S, Farooq W. Impact of media on development of eating disorders in young females of Pakistan. International Journal of Psychological Studies. 2011; 3(1):122. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v3n1p122]

- Polce-Lynch M, Myers BJ, Kilmartin CT, Forssmann-Falck R, Kliewer W. Gender and age patterns in emotional expression, body image, and self-esteem: A qualitative analysis. Sex Roles. 1998; 38(11):1025-48. [DOI:10.1023/A:1018830727244]

- Rehman AU, Nawal A, Sarwar MM, Mehmood H, Majid B. Modeling media exposure, appearance-related social comaparison, thin-ideal internalization, body image disturbance and academic achievement of female university students. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government. 2021; 27(3):2570-82. [Link]

- Harrison K. The body electric: Thin-ideal media and eating disorders in adolescents. Journal of Communication. 2000; 50(3):119-43. [DOI:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02856.x]

- Galioto R, Crowther JH. The effects of exposure to slender and muscular images on male body dissatisfaction. Body Image. 2013; 10(4):566-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.07.009] [PMID]

- Casale S, Gemelli G, Calosi C, Giangrasso B, Fioravanti G. Multiple exposure to appearance-focused real accounts on Instagram: Effects on body image among both genders. Current Psychology. 2021; 40(6):2877-86. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-019-00229-6]

- Olmsted MP, McFarlane T. Body weight and body image. BMC Women’s Health. 2004; 4(Suppl 1):S5. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fallon A. Culture in the mirror: Sociocultural determinants of body image. Body Images-development, Deviance and Change. 1990; 80-109. [Link]

- McCabe MP, Butler K, Watt C. Media influences on attitudes and perceptions toward the body among adult men and women. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2007; 12(2):101-18. [DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9861.2007.00016.x]

- Cingel DP, Olsen MK. Getting over the hump: Examining curvilinear relationships between adolescent self-esteem and Facebook use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2018; 62(2):215-31. [DOI:10.1080/08838151.2018.1451860]

- Thoma BC, Salk RH, Choukas-Bradley S, Goldstein TR, Levine MD, Marshal MP. Suicidality disparities between transgender and cisgender adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019; 144(5):e20191183. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Najam N, Ashfaq H. Gender differences in physical fitness, body shape satisfaction, and body figure preferences. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 2012 ; 27(2):187-200. [Link]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2022/03/14 | Accepted: 2022/12/3 | Published: 2022/12/22

Received: 2022/03/14 | Accepted: 2022/12/3 | Published: 2022/12/22

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |