Thu, Aug 28, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 29, Issue 2 (Summer 2023)

IJPCP 2023, 29(2): 188-201 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kamalfar S, Mousavi R, Alinaghimaddah S M. Effect of Midazolam on the Incidence of Agitation in Patients Undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. IJPCP 2023; 29 (2) :188-201

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3878-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3878-en.html

1- Development and Clinical Research Unit 5 Azar (DCRU), Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran.

2- Development and Clinical Research Unit 5 Azar (DCRU), Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran. ,mitramaddah2000@yahoo.com

2- Development and Clinical Research Unit 5 Azar (DCRU), Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 3951 kb]

(504 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2246 Views)

Full-Text: (481 Views)

Introduction

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) involves inducing general seizures by electrical stimulation of the brain. It has become one of the main methods to treat severe psychiatric disorders [1-4]. Restlessness or agitation is a common adverse effect of ECT. Restlessness in patients treated with ECT increases the risk of harm to patients and health providers. Therefore, the management and prevention of this symptom is of great importance [5, 6]. For this reason, several anesthesia drugs have been introduced to control these complications [2, 7, 8, 9, 10]. The used drug should have low side effects and cause less hemodynamic changes [4, 9, 10]. The prescription of anesthetic drugs and cardiovascular effects that occur during treatment with ECT have caused challenges for the anesthesiologist. Successful and safe ECT depends on the correct selection of anesthetics for each patient according to concomitant medications and previous illnesses [4]. This study aims to investigate the effect of midazolam on agitation in patients undergoing ECT.

Methods

This double-blinded clinical trial was conducted on 80 patients (aged 18-75 years) diagnosed with psychotic disorders indicating the need for ECT according to the opinion of a psychiatrist. Based on the study by Shah et al. [21], the sample size was determined 43 people for each group. Patients were selected by a convenience sampling method from the psychiatric ward of 5 Azar Hospital affiliated to Golestan University of Medical Sciences and were randomly allocated by using envelopes to two groups of A (midazolam group) and B (placebo). Inclusion criteria were fasting, no history of pseudocholinesterase deficiency, and being a candidate for receiving ECT. Exclusion criteria were: Allergy to the anesthesia drugs, seizure symptoms, frequent and severe vomiting, prolonged seizure for more than 125 seconds, need for more anesthetic drugs for induction, and failure to receive or need for the repeat of ECT.

In both groups, only one anesthesiologist monitored and preoxygenated the patients before the induction of anesthesia. In the control group, 2-cc distilled water was injected, while in the intervention group, patients received 0.02-0.01 mg/kg midazolam injection in 4 sessions. After 3-4 minutes, 0.5-mg atropine was intravenously injected in both groups to prevent parasympathetic complications, 2 mg/kg nesdonal for induction of anesthesia, and 0.5 mg/kg succinylcholine for muscle relaxation. Then, the ECT was performed by a neuropsychologist. After the end of electrical seizures, the patient received oral suctioning and oxygen therapy to return to breathing state. After the end of ECT, vital signs and oxygen levels of the patient were checked. Then, the patient was transferred to the recovery ward, and after full consciousness, they were discharged from the recovery ward. Data were collected using a demographic/clinical form and the Richmond agitation sedation scale (RASS).

The clinical information included the diagnosis of disease, hospitalization appointment, history of treatment with ECT, history of drug addiction, history of smoking, and vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen level). The RASS was used to evaluate agitation immediately and one hour after ECT. It measures 5 levels of agitation-sedation, and its scores range from -5 to +4. The zero score shows the state of calmness and alertness. The reliability and validity of the Persian version of this tool have been confirmed by Tadrisi et al. [22]. The RASS was completed by one nurse who was always present in the treatment environment. Data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 18 software with independent t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and chi-square test. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

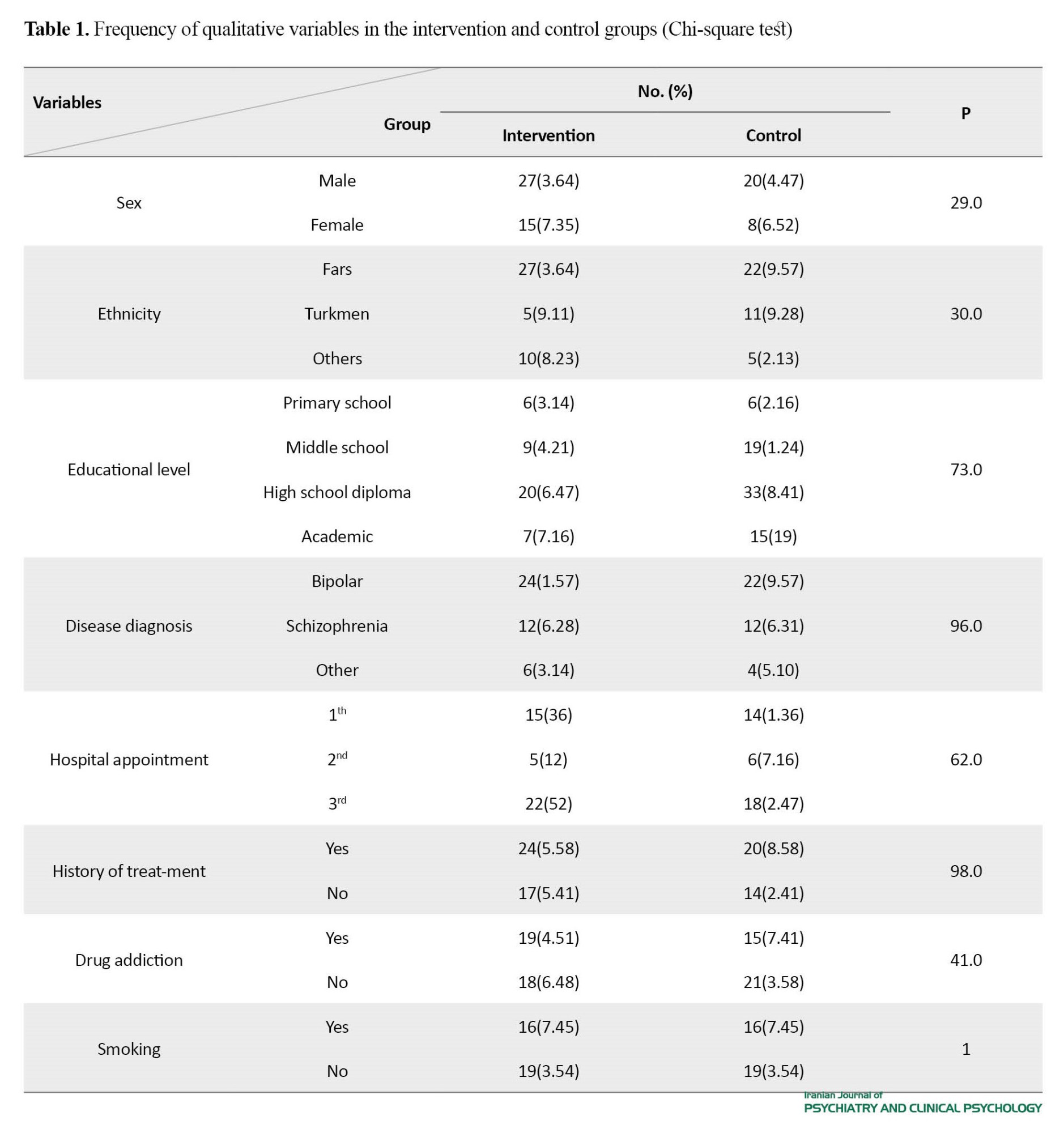

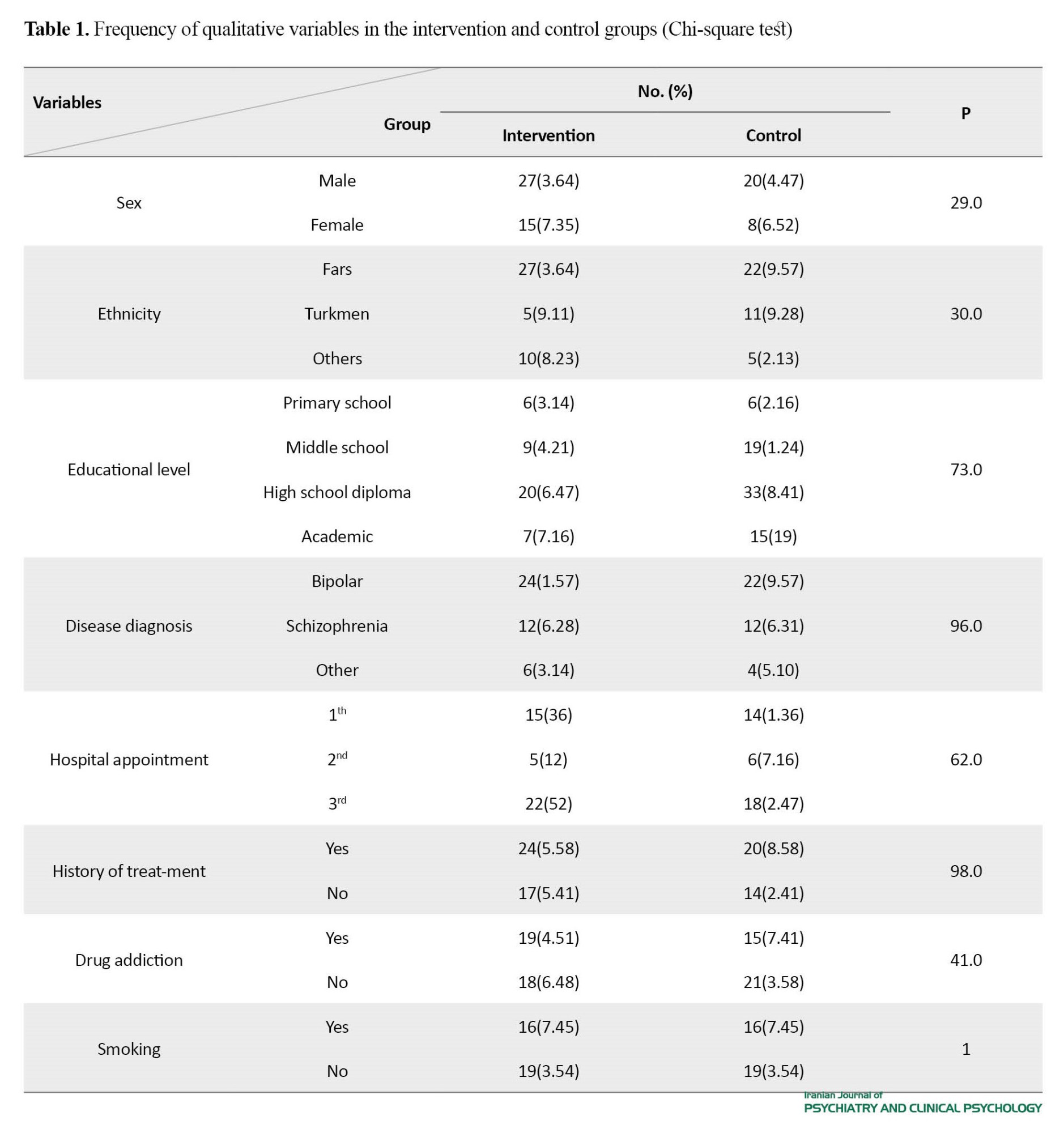

In this study, the data of 42 patients in the midazolam group (mean age: 39.45±10.81 years) and 38 in the placebo group (mean age: 37.92±10.34 years) were analyzed. The mean weight of patients was 70.48±19.56 kg in the intervention group and 71.31±15.17 kg in the control group. The two groups were homogeneous in terms of age, weight, gender, ethnicity, educational level, disease diagnosis, history of treatment with ECT, history of drug addiction, and history of smoking (Table 1).

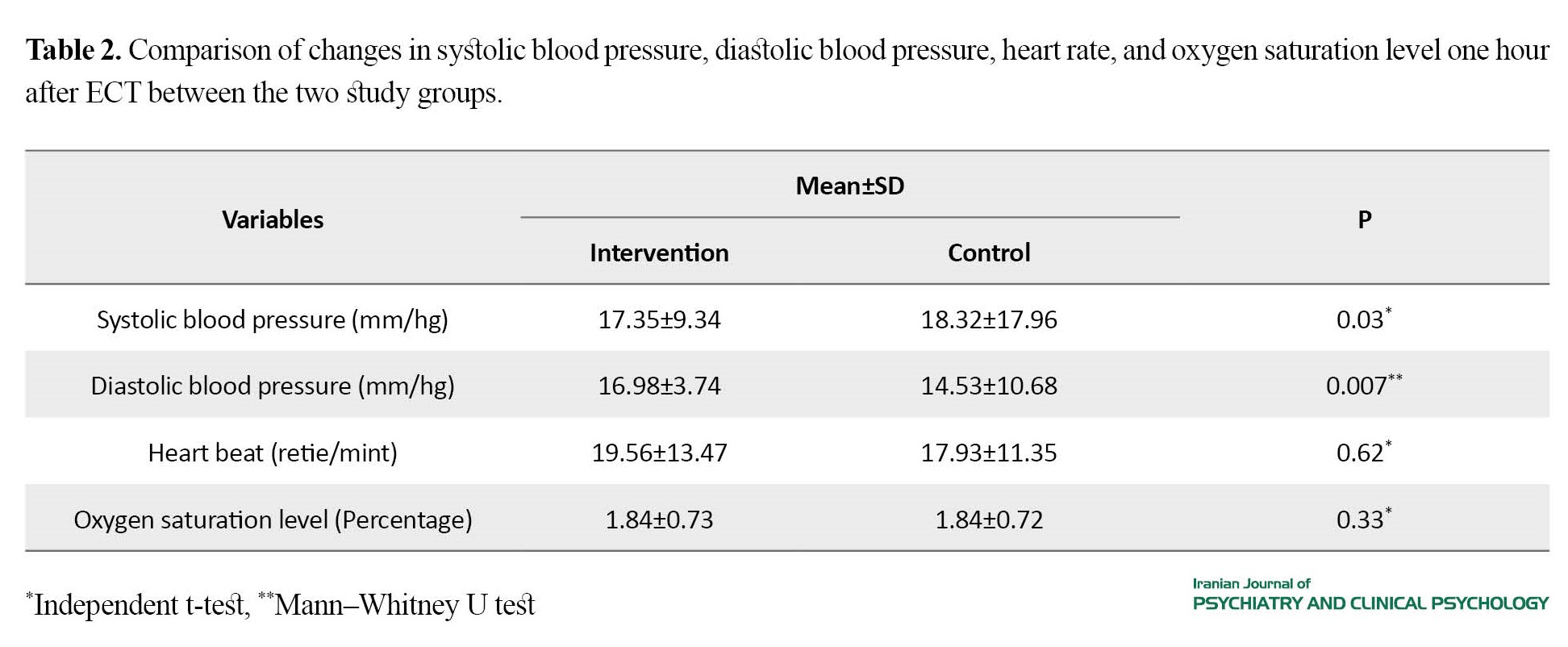

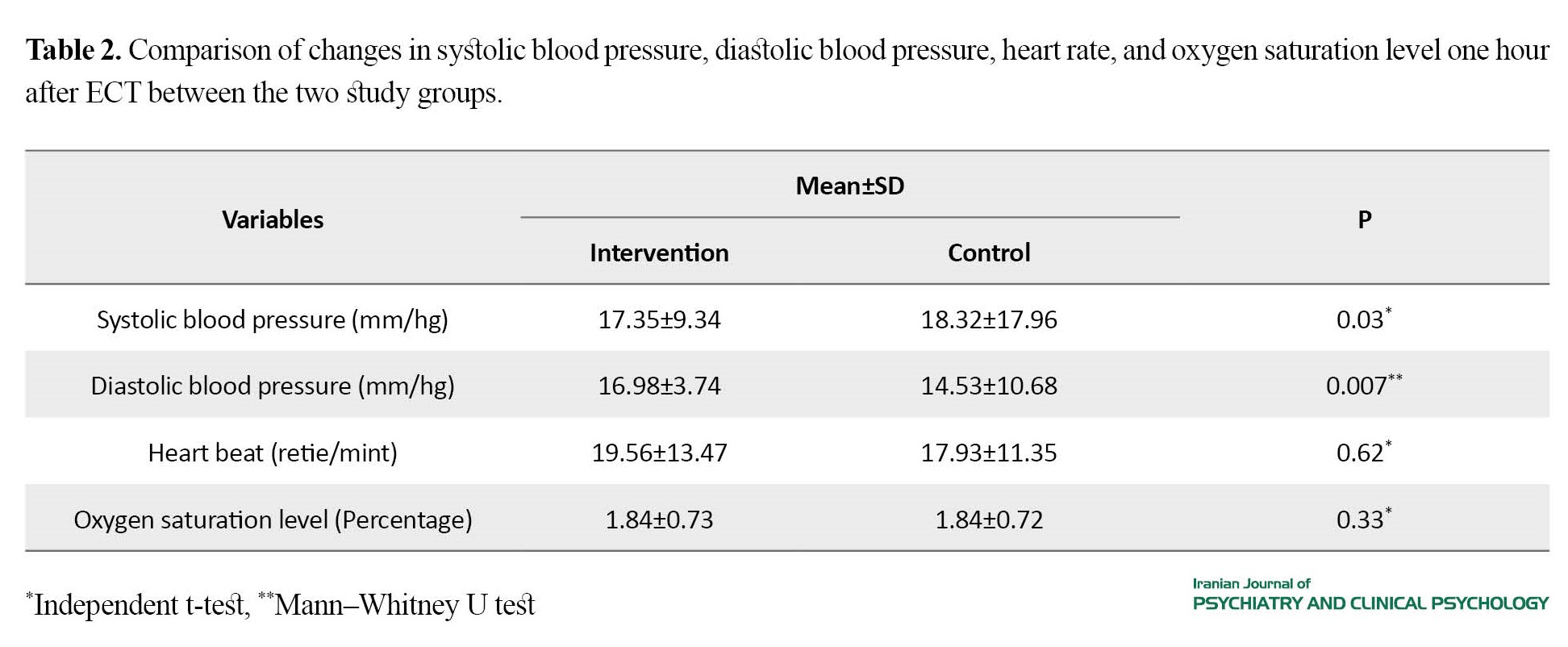

The average changes in systolic (P=0.03) and diastolic (P=0.007) blood pressures one hour after the intervention in the midazolam group were lower than in the control group. The average changes in heart rate and arterial oxygen saturation did not show statistically significant differences between the two groups (Table 2).

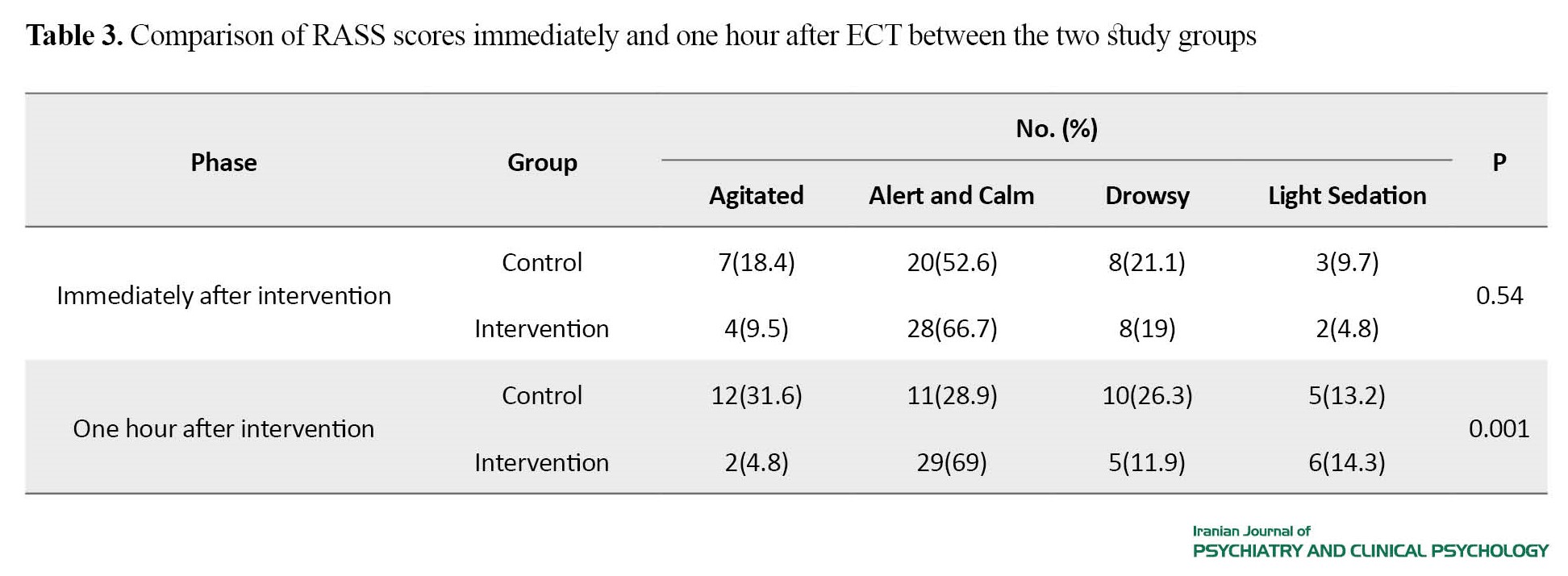

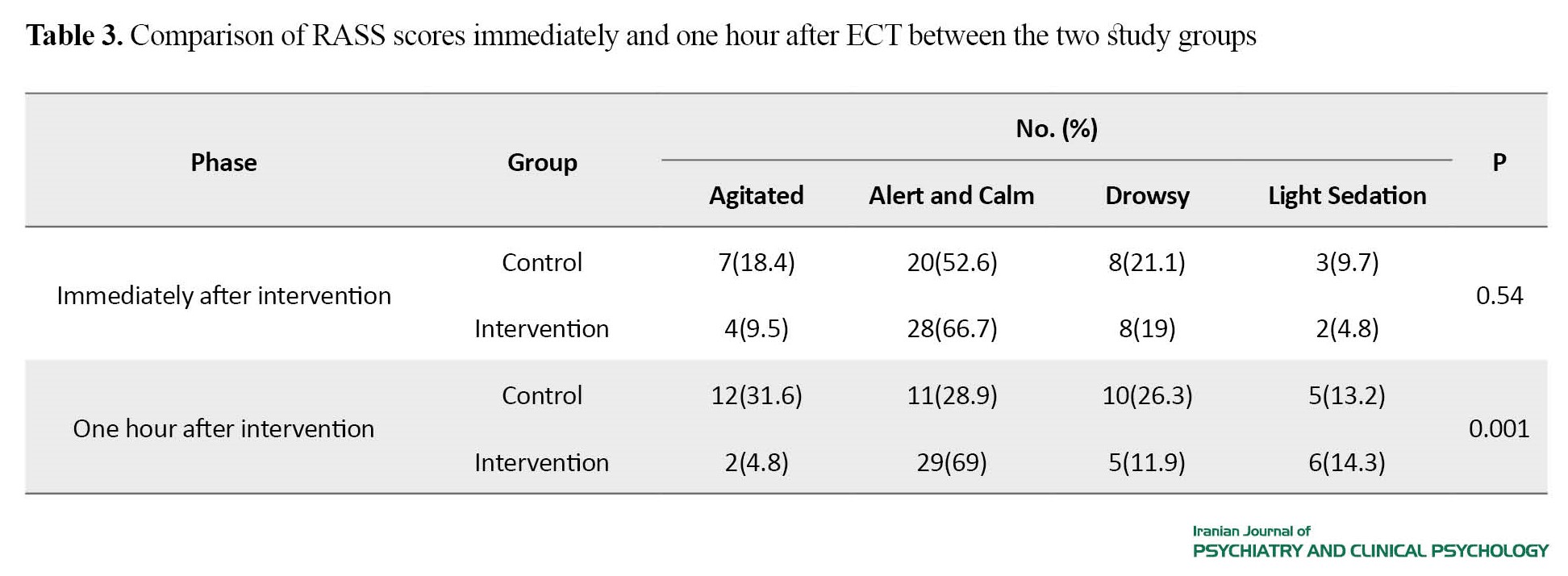

The mean seizure duration was 25.22±10.55 seconds in the intervention group and 37.44±12.10 seconds in the control group. The mean seizure duration immediately after ECT was significantly different in the two groups (P=0.001). Immediately after the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of agitation between the two groups. However, one hour after the intervention, a significant difference was reported (Table 3).

Discussion

In our study, the mean seizure duration after ECT in the intervention group was significantly reduced compared to the control group, but this reduction was within the therapeutic range. Also, 69% of patients in the intervention group were alert and calm based on the RASS score, while this rate in the control group was 28.9%. Therefore, patients in the intervention group had a calmer state than those in the control group in terms of the RASS score. These results are consistent with the results of the studies by Mizrak et al. [23], Nazem alRaaya et al. [24], Masoudifar et al. [19], but are against the results of Jacob et al. [26]. In our study, there was no significant difference in the mean heart rate between the two study groups, but the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels in the midazolam group was significantly lower than in the control group. This is consistent with the results of Alijanpour et al. [27], but is against the results of Nazem alRaaya et al. [28]. The discrepancies can be due to differences in the study population, dosage of used drugs, assessment tools, and time.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.454) and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20170108031818N3).

Funding

This study was extracted from the thesis of Shayan Kamalfar in Anesthesiology, funded by Golestan University of Medical Sciences

Authors contributions

The authors contributed equally to preparing this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

TThe authors would like to thank Golestan University of Medical Sciences , Clinical Research Development Unit and the Psychiatric ward of 5 Azar Hospital, Exir Pharmaceutical Company, and the participants for their support and cooperation.

Refrences

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) involves inducing general seizures by electrical stimulation of the brain. It has become one of the main methods to treat severe psychiatric disorders [1-4]. Restlessness or agitation is a common adverse effect of ECT. Restlessness in patients treated with ECT increases the risk of harm to patients and health providers. Therefore, the management and prevention of this symptom is of great importance [5, 6]. For this reason, several anesthesia drugs have been introduced to control these complications [2, 7, 8, 9, 10]. The used drug should have low side effects and cause less hemodynamic changes [4, 9, 10]. The prescription of anesthetic drugs and cardiovascular effects that occur during treatment with ECT have caused challenges for the anesthesiologist. Successful and safe ECT depends on the correct selection of anesthetics for each patient according to concomitant medications and previous illnesses [4]. This study aims to investigate the effect of midazolam on agitation in patients undergoing ECT.

Methods

This double-blinded clinical trial was conducted on 80 patients (aged 18-75 years) diagnosed with psychotic disorders indicating the need for ECT according to the opinion of a psychiatrist. Based on the study by Shah et al. [21], the sample size was determined 43 people for each group. Patients were selected by a convenience sampling method from the psychiatric ward of 5 Azar Hospital affiliated to Golestan University of Medical Sciences and were randomly allocated by using envelopes to two groups of A (midazolam group) and B (placebo). Inclusion criteria were fasting, no history of pseudocholinesterase deficiency, and being a candidate for receiving ECT. Exclusion criteria were: Allergy to the anesthesia drugs, seizure symptoms, frequent and severe vomiting, prolonged seizure for more than 125 seconds, need for more anesthetic drugs for induction, and failure to receive or need for the repeat of ECT.

In both groups, only one anesthesiologist monitored and preoxygenated the patients before the induction of anesthesia. In the control group, 2-cc distilled water was injected, while in the intervention group, patients received 0.02-0.01 mg/kg midazolam injection in 4 sessions. After 3-4 minutes, 0.5-mg atropine was intravenously injected in both groups to prevent parasympathetic complications, 2 mg/kg nesdonal for induction of anesthesia, and 0.5 mg/kg succinylcholine for muscle relaxation. Then, the ECT was performed by a neuropsychologist. After the end of electrical seizures, the patient received oral suctioning and oxygen therapy to return to breathing state. After the end of ECT, vital signs and oxygen levels of the patient were checked. Then, the patient was transferred to the recovery ward, and after full consciousness, they were discharged from the recovery ward. Data were collected using a demographic/clinical form and the Richmond agitation sedation scale (RASS).

The clinical information included the diagnosis of disease, hospitalization appointment, history of treatment with ECT, history of drug addiction, history of smoking, and vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen level). The RASS was used to evaluate agitation immediately and one hour after ECT. It measures 5 levels of agitation-sedation, and its scores range from -5 to +4. The zero score shows the state of calmness and alertness. The reliability and validity of the Persian version of this tool have been confirmed by Tadrisi et al. [22]. The RASS was completed by one nurse who was always present in the treatment environment. Data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 18 software with independent t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and chi-square test. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

In this study, the data of 42 patients in the midazolam group (mean age: 39.45±10.81 years) and 38 in the placebo group (mean age: 37.92±10.34 years) were analyzed. The mean weight of patients was 70.48±19.56 kg in the intervention group and 71.31±15.17 kg in the control group. The two groups were homogeneous in terms of age, weight, gender, ethnicity, educational level, disease diagnosis, history of treatment with ECT, history of drug addiction, and history of smoking (Table 1).

The average changes in systolic (P=0.03) and diastolic (P=0.007) blood pressures one hour after the intervention in the midazolam group were lower than in the control group. The average changes in heart rate and arterial oxygen saturation did not show statistically significant differences between the two groups (Table 2).

The mean seizure duration was 25.22±10.55 seconds in the intervention group and 37.44±12.10 seconds in the control group. The mean seizure duration immediately after ECT was significantly different in the two groups (P=0.001). Immediately after the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of agitation between the two groups. However, one hour after the intervention, a significant difference was reported (Table 3).

Discussion

In our study, the mean seizure duration after ECT in the intervention group was significantly reduced compared to the control group, but this reduction was within the therapeutic range. Also, 69% of patients in the intervention group were alert and calm based on the RASS score, while this rate in the control group was 28.9%. Therefore, patients in the intervention group had a calmer state than those in the control group in terms of the RASS score. These results are consistent with the results of the studies by Mizrak et al. [23], Nazem alRaaya et al. [24], Masoudifar et al. [19], but are against the results of Jacob et al. [26]. In our study, there was no significant difference in the mean heart rate between the two study groups, but the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels in the midazolam group was significantly lower than in the control group. This is consistent with the results of Alijanpour et al. [27], but is against the results of Nazem alRaaya et al. [28]. The discrepancies can be due to differences in the study population, dosage of used drugs, assessment tools, and time.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.454) and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20170108031818N3).

Funding

This study was extracted from the thesis of Shayan Kamalfar in Anesthesiology, funded by Golestan University of Medical Sciences

Authors contributions

The authors contributed equally to preparing this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

TThe authors would like to thank Golestan University of Medical Sciences , Clinical Research Development Unit and the Psychiatric ward of 5 Azar Hospital, Exir Pharmaceutical Company, and the participants for their support and cooperation.

Refrences

- Ding Z, White PF. Anesthesia for electroconvulsive therapy. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2002; 94(5):1351-64. [DOI:10.1097/00000539-200205000-00057] [PMID]

- Jarineshin H, Kashani S, Fekrat F, Vatankhah M, Golmirzaei J, Alimolaee E, et al. Seizure duration and hemodynamic state during electroconvulsive therapy: Sodium thiopental versus propofol. Global Journal of Health Science. 2015; 8(2):126-31. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n2p126] [PMID]

- Padhi PP, Bhardwaj N, Yaddanapudi S. Effect of premedication with oral midazolam on preoperative anxiety in children with history of previous surgery - A prospective study. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018; 62(12):958-62. [DOI:10.4103/ija.IJA_529_18] [PMID]

- Wagner KJ, Möllenberg O, Rentrop M, Werner C, Kochs EF. Guide to anaesthetic selection for electroconvulsive therapy. CNS Drugs. 2005; 19(9):745-58. [DOI:10.2165/00023210-200519090-00002] [PMID]

- Sterina E, Gregory N, Hermida AP. Acute and prophylactic management of postictal agitation in electroconvulsive therapy. The Journal of ECT. 2023; 39(3):136-40. [DOI:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000886] [PMID]

- Allen ND, Allison CL, Golebiowski R, Janowski JPB, LeMahieu AM, Geske JR, et al. Factors associated with postictal agitation after electroconvulsive therapy. The Journal of ECT. 2022; 38(1):60-1. [DOI:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000807] [PMID]

- Moshiri E, Modir H, Bagheri N, Mohammadbeigi A, Jamilian H, Eshrati B. Premedication effect of dexmedetomidine and alfentanil on seizure time, recovery duration, and hemodynamic responses in electroconvulsive therapy. Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia. 2016; 19(2):263-8. [DOI:10.4103/0971-9784.179618] [PMID]

- Boere E, Birkenhäger TK, Groenland TH, van den Broek WW. Beta-blocking agents during electroconvulsive therapy: A review. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2014; 113(1):43-51. [DOI:10.1093/bja/aeu153] [PMID]

- Soehle M, Bochem J. Anesthesia for electroconvulsive therapy. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2018; 31(5):501-5. [DOI:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000624] [PMID]

- Blanch J, Martínez-Pallí G, Navinés R, Arcega JM, Imaz ML, Santos P, et al. Comparative hemodynamic effects of urapidil and labetalol after electroconvulsive therapy.The Journal of ECT. 2001; 17(4):275-9. [DOI:10.1097/00124509-200112000-00007] [PMID]

- Zahavi GS, Dannon P. Comparison of anesthetics in electroconvulsive therapy: An effective treatment with the use of propofol, etomidate, and thiopental. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2014; 10:383-9. [DOI:10.2147/NDT.S58330] [PMID]

- Malekshoar M, Jarineshin H, kashani S, Fekrat F, Raz R, Vatankhah M. [Assessment of propofol and etomidate effect on the duration of convulsion and hemodynamic responses to electroconvulsive therapy (Persian)]. Journal of Anesthesiology and Pain. 2017; 8(2):53-60. [Link]

- Tadler SC, Mickey BJ. Emerging evidence for antidepressant actions of anesthetic agents. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2018; 31(4):439-45. [DOI:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000617] [PMID]

- Mason KP, Seth N. The pearls of pediatric sedation: Polish the old and embrace the new. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2019; 85(10):1105-17. [DOI:10.23736/S0375-9393.19.13547-X] [PMID]

- Gencer M, Sezen O. A study comparing the effect of premedication with intravenous midazolam or dexmedetomidine on ketamine-fentanyl sedoanalgesia in burn patients: A randomized clinical trial. Burns. 2021; 47(1):101-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.burns.2020.05.027] [PMID]

- Lang B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Lin Y, Fu Y, Chen S. A comparative evaluation of dexmedetomidine and midazolam in pediatric sedation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with trial sequential analysis. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2020; 26(8):862-75. [DOI:10.1111/cns.13377] [PMID]

- Park JW, Min BH, Park SJ, Kim BY, Bae SI, Han SH, et al. Midazolam premedication facilitates mask ventilation during induction of general anesthesia: A randomized clinical trial. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2019; 129(2):500-6. [DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000003707] [PMID]

- Loimer N, Hofmann P, Chaudhry HR. Midazolam shortens seizure duration following electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1992; 26(2):97-101. [DOI:10.1016/0022-3956(92)90001-5] [PMID]

- Masoudifar M, Nazemroaya B, Raisi M. Comparative study of the effect of midazolam administration before and after seizures on the prevention of complications in children undergoing electroconvulsive therapy compared with a control group. Archives of Anesthesia and Critical Care. 2022; 8(1):53-9. [DOI:10.18502/aacc.v8i1.8245]

- Shah PJ, Dubey KP, Sahare KK, Agrawal A. Intravenous dexmedetomidine versus propofol for intraoperative moderate sedation during spinal anesthesia: A comparative study. Journal of Anaesthesiology, Clinical Pharmacology. 2016; 32(2):245-9. [DOI:10.4103/0970-9185.168172] [PMID]

- Shah PJ, Dubey KP, Watti C, Lalwani J. Effectiveness of thiopentone, propofol and midazolam as an ideal intravenous anaesthetic agent for modified electroconvulsive therapy: A comparative study. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2010; 54(4):296-301. [DOI:10.4103/0019-5049.68371] [PMID]

- Tadrisi SD, Madani SJ, Farmand F, Ebadi A, Karimi Zarchi AA, Saghafinia M, et al. [Richmond agitation-sedation scale validity and reliability in intensive care unit adult patients Persian version (Persian)]. Critical Care Nursing. 2009; 2(1):15-21. [Link]

- Mizrak A, Koruk S, Ganidagli S, Bulut M, Oner U. Premedication with dexmedetomidine and midazolam attenuates agitation after electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of Anesthesia. 2009; 23(1):6-10. [DOI:10.1007/s00540-008-0695-2] [PMID]

- Nazemroaya B, Mohammadi A, Najafian J, Moradi-Farsani D. [Effect of preemptive midazolam on post-electroconvulsive-therapy (ECT) headache, myalgia, and nausea and vomiting (Persian)]. Journal of Isfahan Medical School, 2017. 35(417): p. 26-31. [Link]

- Liston EH, Sones DE. Postictal hyperactive delirium in ECT: Management with midazolam. Convulsive Therapy. 1990; 6(1):19-25. [PMID]

- Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Grounds RM, Sarapohja T, Garratt C, Pocock SJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam or propofol for sedation during prolonged mechanical ventilation: Two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2012; 307(11):1151-60. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2012.304] [PMID]

- Alijan Poor E,Rabiei S , Mir Shekari S. [A comparison of hemodynamic effects of Midazolam and Thiopental in induction of anesthesia (Persian)]. Journal of Babol University of Medical Sciences. 2000; 2(2):27-32. [Link]

- Nazemroaya B, Mousavi SM. Comparison of premedication with low-dose midazolam versus etomidate for reduction of etomidate-induced myoclonus during general anesthesia for electroconvulsive therapy: A randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. 2019; 9(6):e94388. [DOI:10.5812/aapm.94388] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2023/04/5 | Accepted: 2023/06/27 | Published: 2023/07/1

Received: 2023/04/5 | Accepted: 2023/06/27 | Published: 2023/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |