Tue, Jul 1, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 29, Issue 1 (Spring 2023)

IJPCP 2023, 29(1): 94-117 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khan A, Nasreen R. Investigating the Relationship Between Perceived Impact of Terrorist Attacks, Resilience, and Religious Beliefs on Death Anxiety in Students in Islamabad. IJPCP 2023; 29 (1) :94-117

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3581-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3581-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, University of Wah, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. , ayeshainam946@gmail.com

2- Islamabad model college for girls, i-8/3, Islamabad, Pakistan.

2- Islamabad model college for girls, i-8/3, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Full-Text [PDF 6019 kb]

(591 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4091 Views)

Full-Text: (546 Views)

1. Introduction

Terrorism is one of the world’s biggest challenges nowadays and its causes and consequences are difficult to specify. It induces terror and fear in the public and causes people to be victimized both directly (physically) and indirectly (psychologically). Pakistan is included in countries where such cruel acts (suicide bombing, target killings, and serial bombing) occur almost regularly in the past few years. Researchers believe that in such situations, people may have a higher level of death anxiety. A terrorist attack is defined as the threatening or actual use of illegal force and violence by a nonstate actor to achieve a political, economic, religious, or social purpose through fear, compulsion, or intimidation. According to the global terrorism database (GTD), terrorism reached a new level after the attack on the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. This attack had Middle Eastern and European roots, and it has religious and secular dimensions.

Terrorism is defined as the deliberate acts of violence against civilians to fulfill some ideological, religious, or political goals [1]. Since September 11, 2011, the world has spent hundreds of billions of dollars on counterterrorism measures against 4 hijackings [2]. Terrorism is a very complex subject, and many researchers have shed light on it, maintaining that there are numerous reasons and causes involved in such acts. Terrorist attacks in Pakistan have taken 36 495 lives and injured 27 985 persons in recent years as a result of 3482 bombings and 281 suicide attacks [3].

Ethnicity, illiteracy, population growth, income inequality, high unemployment rate, inflation, poverty, high political instability, and injustice are the factors that contribute to terrorism in Pakistan [4, 5, 6]. Pakistan is playing its role as a front line against terrorism after 9/11. As a result, such measures are increasing day by day in the country. The psychological well-being of individuals is harmed because of these terrorist actions. According to some research conducted in Pakistan, terrorist activities have affected the mental health of people [5, 6, 7]. Terrorist attacks have an impact on people’s mental health as they get anxious, worried, and depressed as a result of such attacks. The majority of the time, people are emotionally upset and ill. And, given the recent wave of terrorism that has left people fearful for their safety as well as for their families, they do not consider themselves or their families safe and secure in this environment. They are also fearful about death and such uncertain fearful situations induce death anxiety among them. To address this problem, a collaborative and non-judgmental approach is important [8]. Terrorist attacks in Pakistan produce a huge and ongoing kind of insecurity among the public as this dread disturbs their routine life along with their financial setup [9].

Research on the public perceptions and the psychological impacts of terrorist attacks has increased in recent years in Western countries because of the occurrence of several high-profile incidences, such as the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the Madrid and London bombings of 2004 and 2005, respectively [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. According to the previous literature, the perceived impact of terrorist attacks includes 1) harming people physically during direct attacks, 2) illness and injury because of toxic substances released in the surrounding (e.g., bomb explosions), 3) disturbed daily life activities by causing secondary stressors (e.g., access to services, such as health care and transportation), 4) psychological distress to those who are directly and indirectly exposed to terrorism, and 5) damage to mental and physical health as a result of intensified fear response [15]. However, these studies have explored the effects of terrorism on mental health. No study has been conducted to investigate the impact of terrorist attacks on death anxiety among directly and indirectly perceived individuals. The present study aims to fill this gap using information from individuals who perceived terrorism from news content or other sources along with those who are the direct victim of terrorist attacks.

Anxiety is an emotion characterized by concerned thoughts, strained feelings, and bodily changes, such as increased blood pressure [16]. Anxiety has many types; one type is death anxiety. Death Anxiety is a psychological phenomenon defined as the dread of destruction, fear of life hereafter, and worries of becoming nothing at all [17]. Fear of death is not a single variable, rather it includes several aspects, such as the loss of individuality, loneliness, or isolation [18]. Studies indicated that constant and prolonged exposure to dreadful and threatening situations, such as terrorist activities, enhances the vulnerability of getting anxious about death [19]. A study was conducted on university students’ level of terrorism catastrophizing, perceived stress, and death anxiety [9]. The finding of this study indicated that terrorism catastrophizing and perceived stress were the considerable and significant predictors of death anxiety. Terrorism is an inevitable reality in the present situation, and the whole world is trapped in its brutal jaws of it. It has been found that constant and prolonged exposure to threatening and combat situations, such as terrorist activities, enhances the vulnerability to obliteration anxiety and fear of death [19].

Resilience is the ability to recover from illness or misfortune. The psychological meaning of resilience is the ability to cope with stressors of daily life activities. The term, resilience, is defined as the ability to recover or spring back [20]. Resilience is considered a set of attributes that help people overcome and successfully cope with adversity and danger [21]. Some researchers have found that repeated exposure to traumatic events can desensitize individuals, creating invulnerability to reduce psychological and physiological distress following future adversities by enhancing their coping ability [25]. Several factors increase resilience to traumatic situations, including the capacity to deal with trauma, mental and physical preparation for the trauma, and past experiences of successful and spontaneous recovery from trauma. Every individual has some degree of resilience while few may be more resilient to one kind of stress than others. In situations where terrorism has become prevalent, collective training, such as methods to cope with these threatening situations is common among people [22]. A study on male traffic police wardens (as the easy targets of terror attacks among security forces) in Lahore City, Pakistan, found a significant negative relationship between resilience and catastrophizing impact of terror attacks [23]. Exposure to a terrorist threat causes physical harm and shatters an individual’s belief and faith about a safe world; however, it simultaneously increases the coping ability of those who face such attacks [24]. Some researchers have found that death anxiety is a perceived inability to achieve major life ambitions and goals and a sense of regret. Death anxiety decreases the coping ability of an individual [25, 26, 15]. We need to educate people to cope with dreadful situations through resilience. This study explores the moderating role of resilience in dreadful situations, such as terrorist attacks. In the samples of Chinese patients, resilience was found to be a protective factor related to anxiety and depression and a protective factor during the pandemic situation [27].

Religion provides a basic framework for addressing and answering death and dying-related questions [18]. Religion indicates that individual differences in death anxiety are mostly caused by their religious belief, rituals, and attitudes. Religious beliefs are the mental representation of an attitude, positively oriented toward the likelihood of something being true [28], while religious behaviors are the rituals that are motivated by religious beliefs [29]. People who believe in the existence of God experience low death anxiety [30]. It is also considered one of the factors that enhances the individual’s coping ability by changing their perspective about life and hereafter and leads them toward a positive path by giving them knowledge about various topics, such as the purpose of life, the meaning of life, and reasons for their creation [31]. People who believe in the existence of God experience low death anxiety [30]. Several studies have reported a moderate relationship between religiosity and death anxiety among Muslim samples from outside the United States [32]. People who believe in the existence of God experience low death anxiety compared to non-believers [30]. A study was conducted to investigate the relationship between religious beliefs and resilience in academic students who had experienced any traumatic event [16]. The results indicated that the practice of religious beliefs improved resilience in students who were injured or witnessed these traumatic events [16]. Religious beliefs boost optimism, resilience, and hope, which reduce death anxiety [33]. Religious coping was revealed to be one of the most important predictors of death anxiety in the elderly [34].

A study was conducted to investigate the relationship between religious beliefs and resilience in students who experienced any traumatic event. The results of the study indicated that the practice of religious beliefs improved resilience in those students who were injured or witnessed these traumatic events [8]. Religious beliefs can provide support through the following ways: enhancing acceptance, endurance, and resilience as they generate peace, providing self-confidence and a sense of purpose, forgiveness toward the individual’s failures, self-giving, positive self-image, and preventing depression, fear, and anxiety [35].

Terrorism is an inevitable reality in the current world as numerous studies have been conducted concerning this subject in Western countries. Pakistan is also facing such terrible situations, however, people are continuing their normal routine life. Literature is scarce on related variables in Eastern countries. The present study will add to this topic’s literature for future researchers. Accordingly, religious beliefs are protective factors in reducing death anxiety resulting from terrorist attacks both directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

Study Objectives

This study aims to explore the following objectives:

To explore the perceived impact of terrorist attacks in terms of dread, lack of control, and extent of exposure to terrorist attacks on the experience of death anxiety among directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

To explore the moderating effect of resilience attributes and religious beliefs in the relationship between the perceived impact of terrorist attacks and the experience of death anxiety.

Methods

Study Samples

The samples were selected via convenience and purposive sampling techniques. We used the quantitative research method in the study. The samples consisted of 359 students, studying in schools, colleges, and universities of Islamabad City and Peshawar City, Pakistan. A total of 70 students were selected from the Army Public College and 89 students were selected from the Bacha Khan University as they were directly exposed to terrorist attacks. The participants for the indirectly exposed category were selected from educational institutions. A total of 50 students were selected from the Federal Medical and Dental College, 120 students from I.M.C.G (Postgraduate) F-7/2 Islamabad, and 30 students from L.M.C.B, G-10/4 Islamabad. Accordingly, the samples helped to compare the direct and perceived impact of terrorist attacks among students of different ages and different educational levels. The distribution of the sample in terms of age was 15-17 years (n=106) and 18-21 years (n=253). The mean age of the samples was 18.70 and the standard deviation (SD) was 2.59. The distribution of the participants in terms of the level of education is given as follows: F.A./F. Sc (n = 132), BA/B. Sc/BS/ BBA (n=152), and M.A/M. Sc/MS/ M. Phil/ M.B.B.S (n=76). Thus, the samples consisted of more participants currently studying their BA/B. Sc/BS.

Inclusion Criteria

The directly perceived individuals were those who were the victim of terrorist activities while those who perceived it through exposure to different social media sites, such as news content, YouTube, and so on were under the category of indirectly perceived individuals.

Exclusion Criteria

The samples in the intensive care unit or rehabilitation centers were not included in this study.

Study Instruments

Following are the four instruments that were used in the present study along with the demographic sheet.

Perceived Impact of Terrorist Attack Scale

This scale was developed by the author of the thesis by Ayesha Khan under the supervision of Dr. Nasreen Rafiq (2016). This questionnaire is based on the risk perception theory of Combs, Fischhoff, Slovic, Lichtenstein, and Read (1978). This questionnaire is in line with the aim of this study, which is to measure the perceived impact of terrorist attacks. The present scale is based on 4 factors of the author’s theory of risk perception: dread, lack of control, knowledge of risk, and the extent of exposure. A self-constructed scale of 27 items was developed from which 18 items were selected, based on the above factors. Then, they were divided into 3 dimensions: extent of exposure, lack of control, and dread. The participants responded to each dimension-related item on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (to a greater extent). Item 23 was inversely scored. At first, this scale was administered to a sample of 95 individuals to establish its psychometric properties and reported the reliability coefficient of α = 0.75 for the full scale.

Death Anxiety Scale

The death anxiety scale (DAS) is a self-report measure that is used in populations facing life-threatening illnesses [33]. DAS includes 15 items that are intended to be rated on a dichotomous scale (true/false) [21]. Higher scores represent a greater amount of fear and anxiety of death in the respondent. Good internal consistency of 0.76 was obtained with 31 participants through the Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 [7] which indicated that the scale is consistent and stable.

The Resilience Scale for Adults

The revised version of the resilience scale for adults (RSA) [37] is used in the present study. This version includes 33 items and 6 subscales, including 1) perception of self, 2) planned future, 3) social competence, 4) structured style, 5) family cohesion, and 6) social resources in which each item was positively stated. This scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of resilience and coping. The α coefficient of RSA is reported in previous studies to be 0.87 [37], indicating that the scale is valid and reliable.

Religiosity Questionnaire

The religiosity questionnaire [13] includes 34 items and 2 subscales, including religious behaviors and religious beliefs. The participants respond to each belief-related item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate strong religious behaviors and beliefs. The internal consistency for the scale was obtained at α = 0.81. Five items (8, 9, 13, 15, and 21) in the present questionnaire were kept negative to control the response bias [13].

Study Procedure

This study was conducted in different phases. At first, a self-constructed demographic sheet was developed. Then, different scales were selected to achieve the objectives of the study. The permission for using the instruments was obtained from the respective authors. Before completing the questionnaire, the educational authorities were contacted and permission for data collection was taken. Next, each participant provided their consent form. The students were briefly informed about the nature and purposes of the research, their anonymity, and the confidentiality of their information, along with their right to withdraw from the study at any point. The questionnaires were administered to the samples after obtaining their informed consent letters. The samples were selected via convenience and purposive sampling techniques. Almost 15 participants withdrew from the study because of privacy issues. A total of 411 questionnaires were collected from the participants. The students returned the completed questionnaires and the survey completion lasted approximately 30 min. The participants were also briefed about how they could inquire about the results of the present research by contacting the department. A total of 12 questionnaires were discarded because of the missing data.

Data Analysis and Results

After the data collection, the data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 23, and process macro. The data were subjected to statistical analyses according to the stated objectives. Mean, SD, and correlation coefficients were carried out on the variables to explore the perceived impacts of terrorist attacks on death anxiety in terms of dread, lack of control, and extent of exposure . The role of resilience attributes and religious beliefs as moderators were also observed.

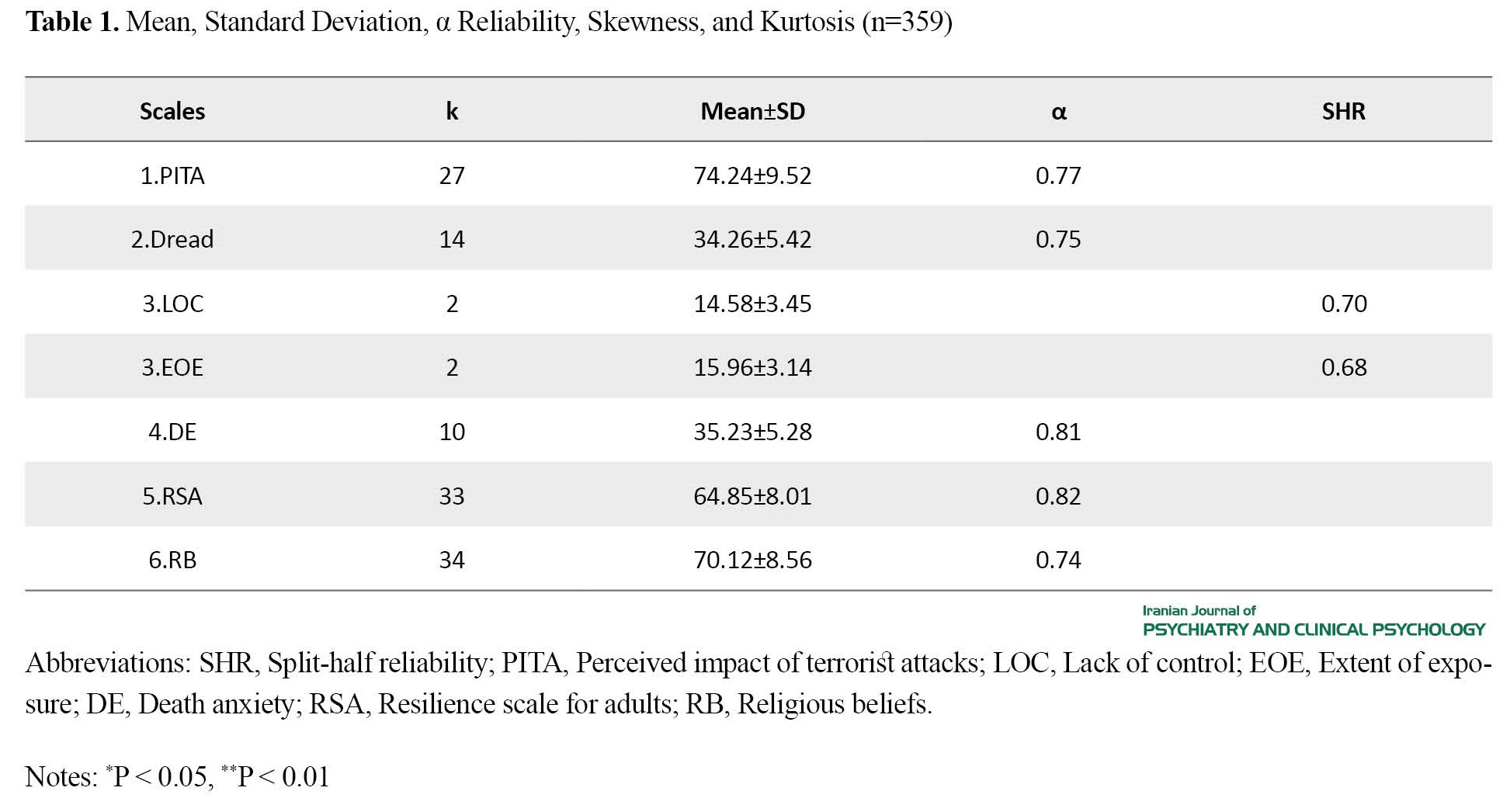

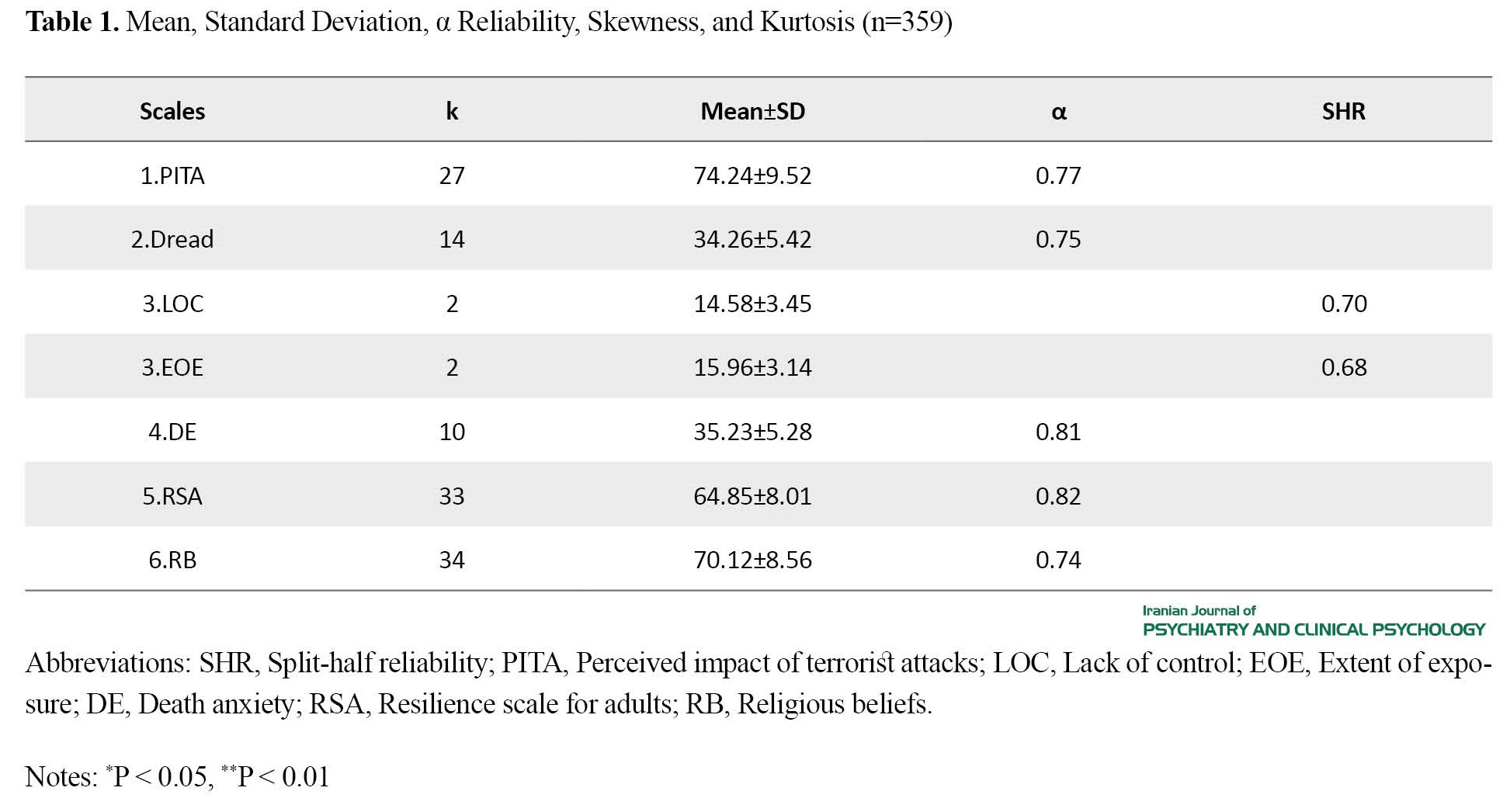

Table 1 shows the mean, SD, α reliability, skewness, and kurtosis for each scale.

The results demonstrate that the α reliability coefficient of all scales is in the accepted range.

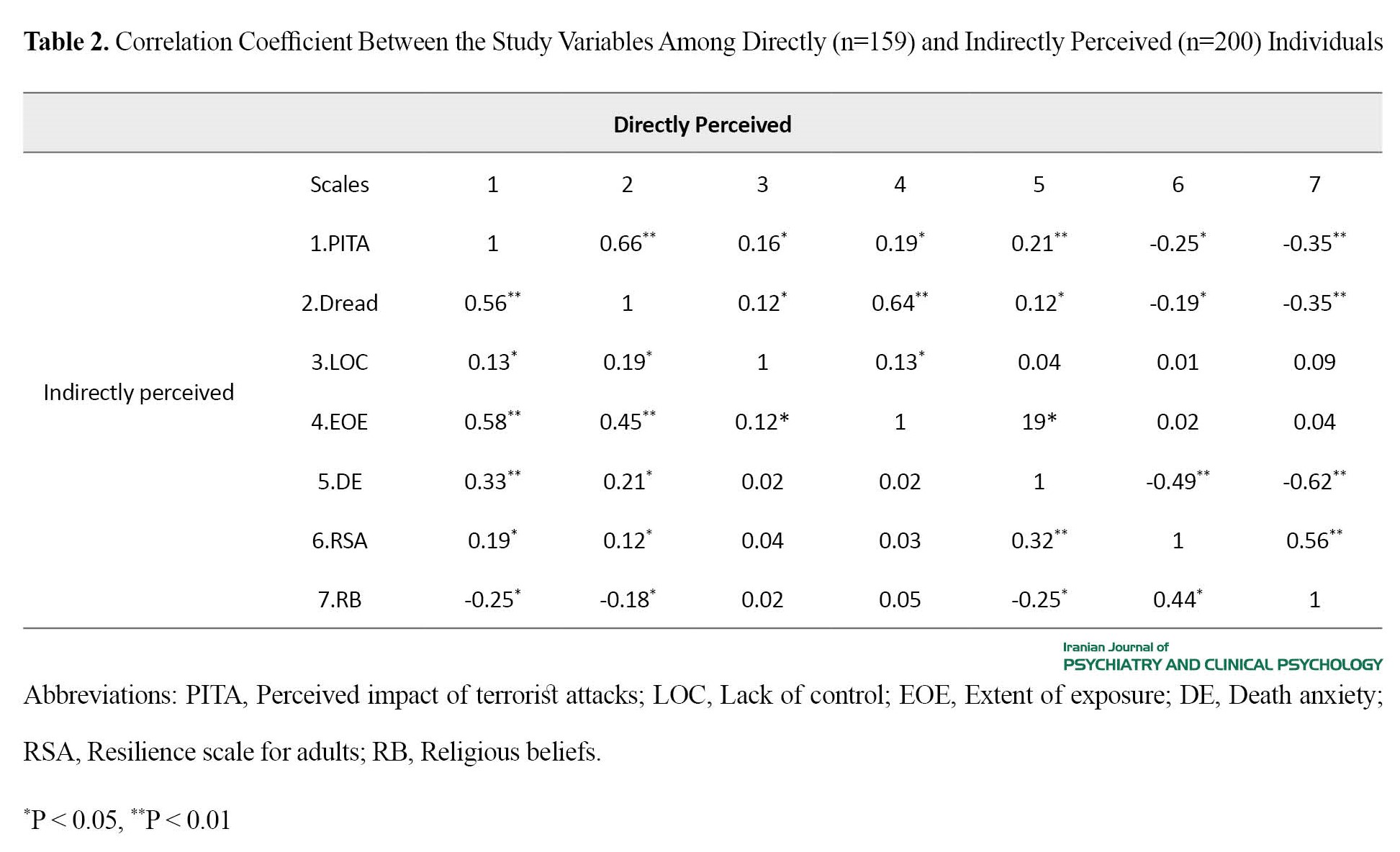

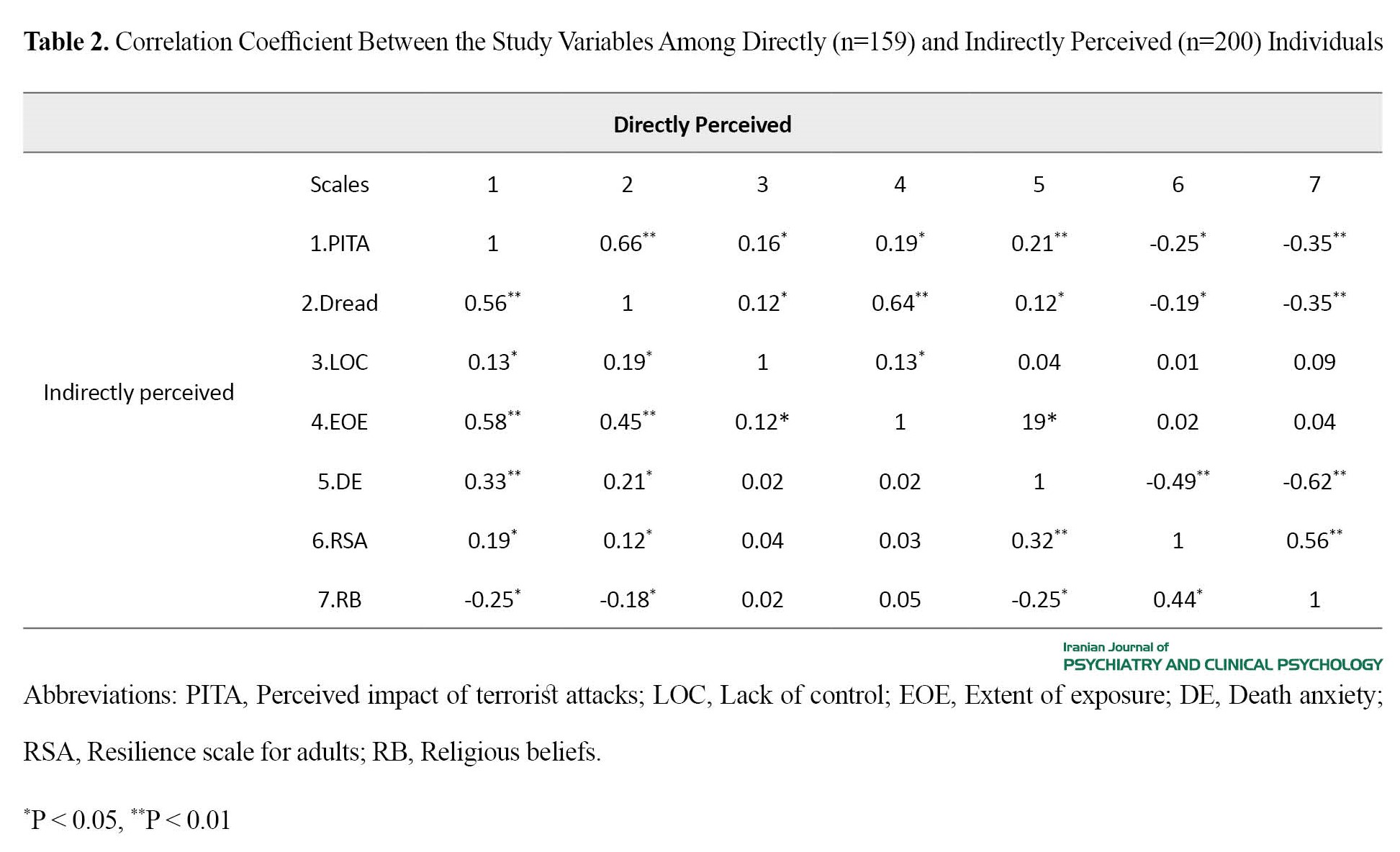

Table 2 shows the positive relationship between the perceived impacts of terrorism and its dimensions (dread, lack of control, exposure) on death anxiety among directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

The table also demonstrates that dread and death anxiety is significantly negatively related to resilient attributes and religious belief, whereas resilience attributes are positively related to religious belief in both directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

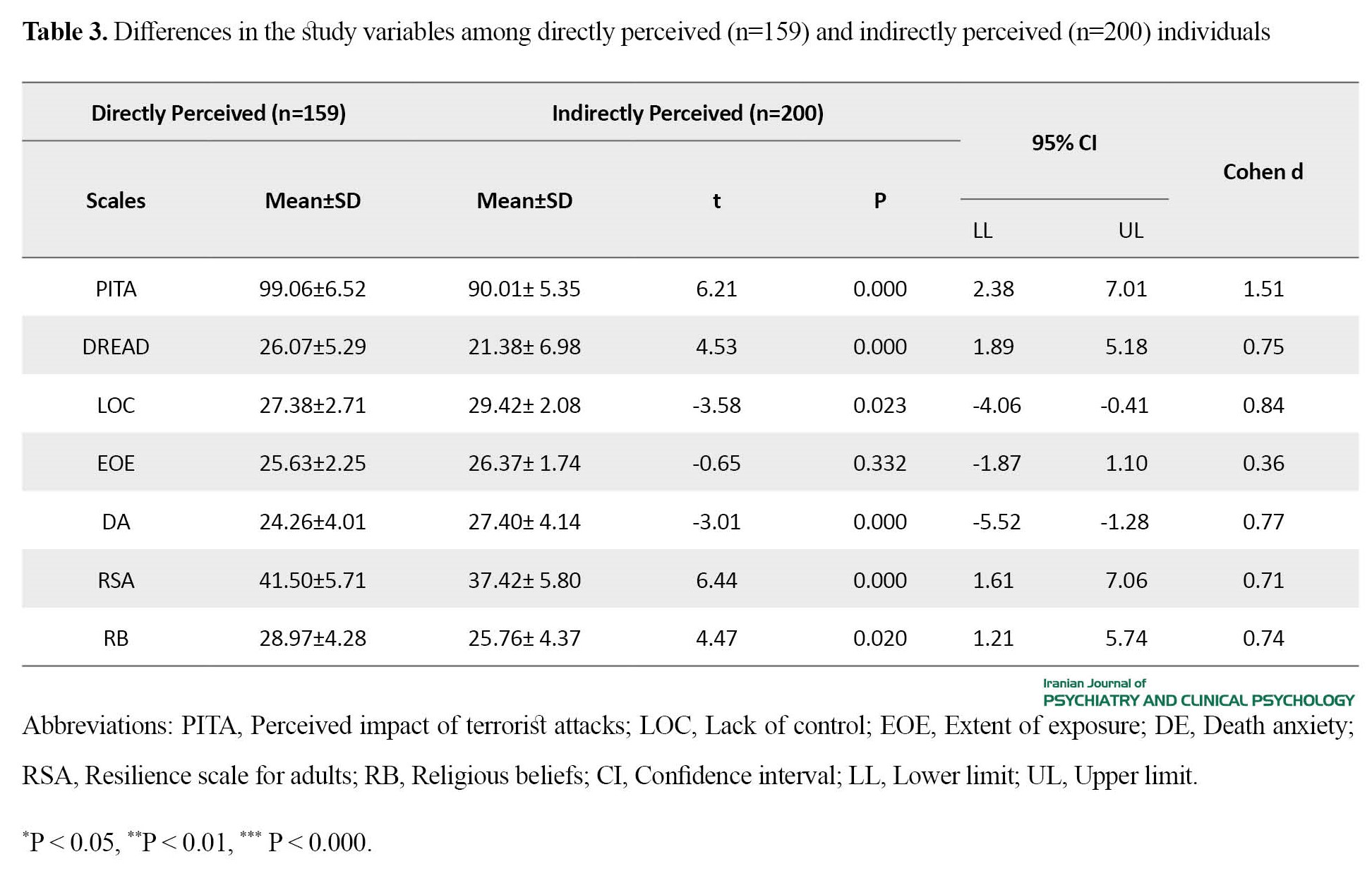

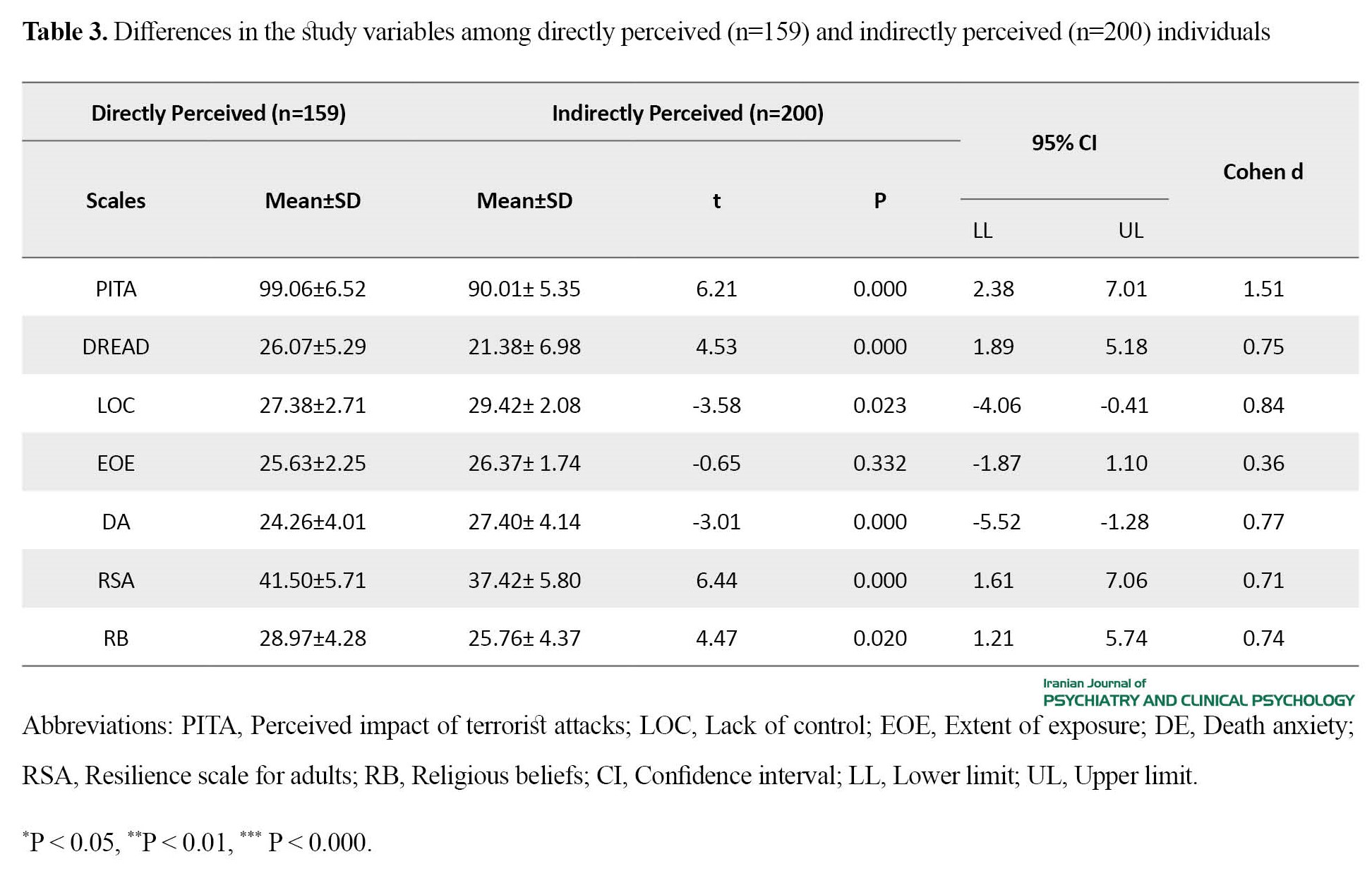

Table 3 shows the difference in the study variables among directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

The table indicates that individuals who were directly exposed to terrorist attacks scored higher on dread, resilience attributes, and religious beliefs but low on death anxiety compared to those who indirectly perceived terrorist attacks.

Moderating Effect of Resilience Attributes and Religious Beliefs for the Relationship Between Perceived Terrorist Attacks and Death Anxiety

The moderating effect of resilient attributes and religious beliefs was also determined for terrorist attacks in predicting death anxiety. The results obtained from the analysis are provided below.

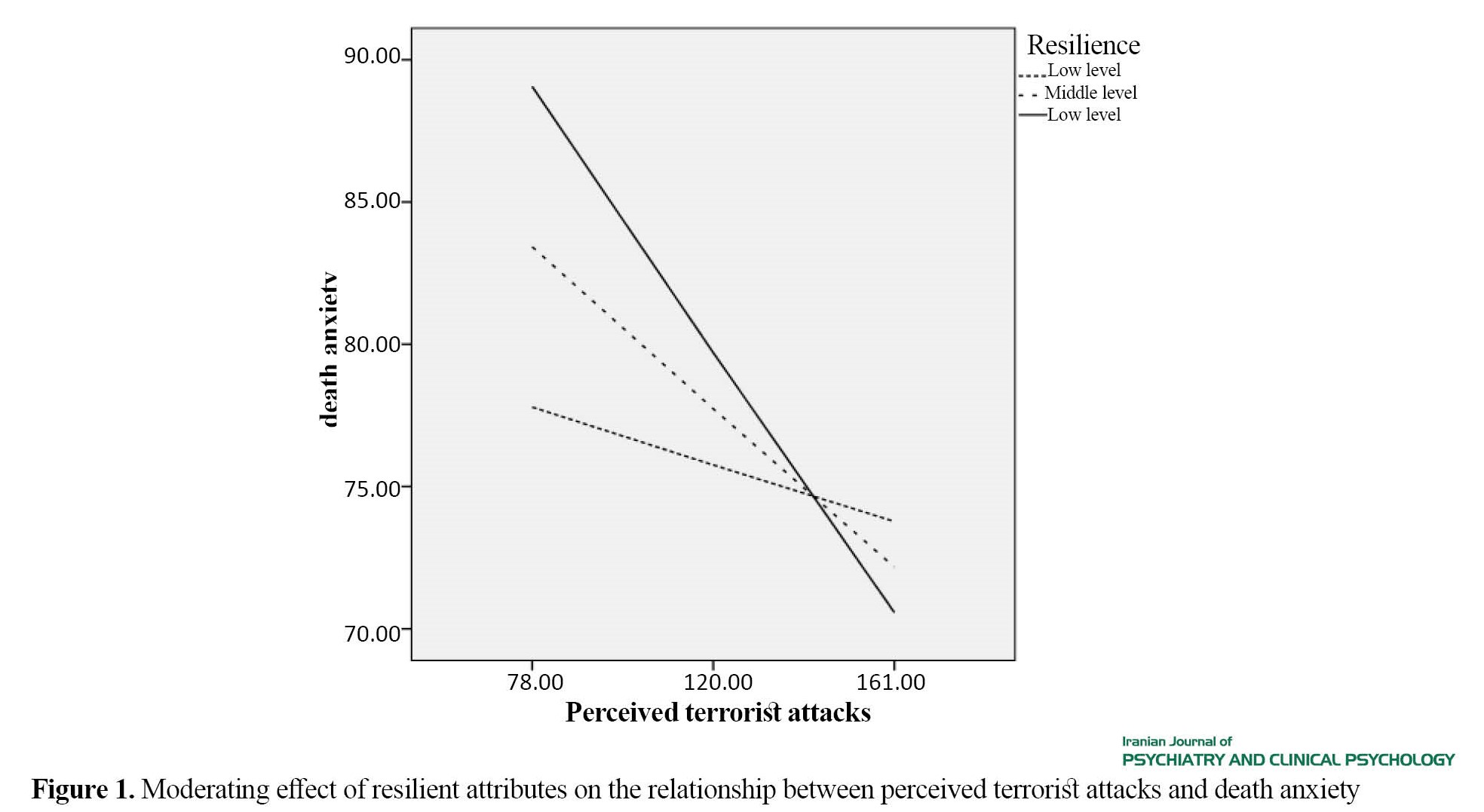

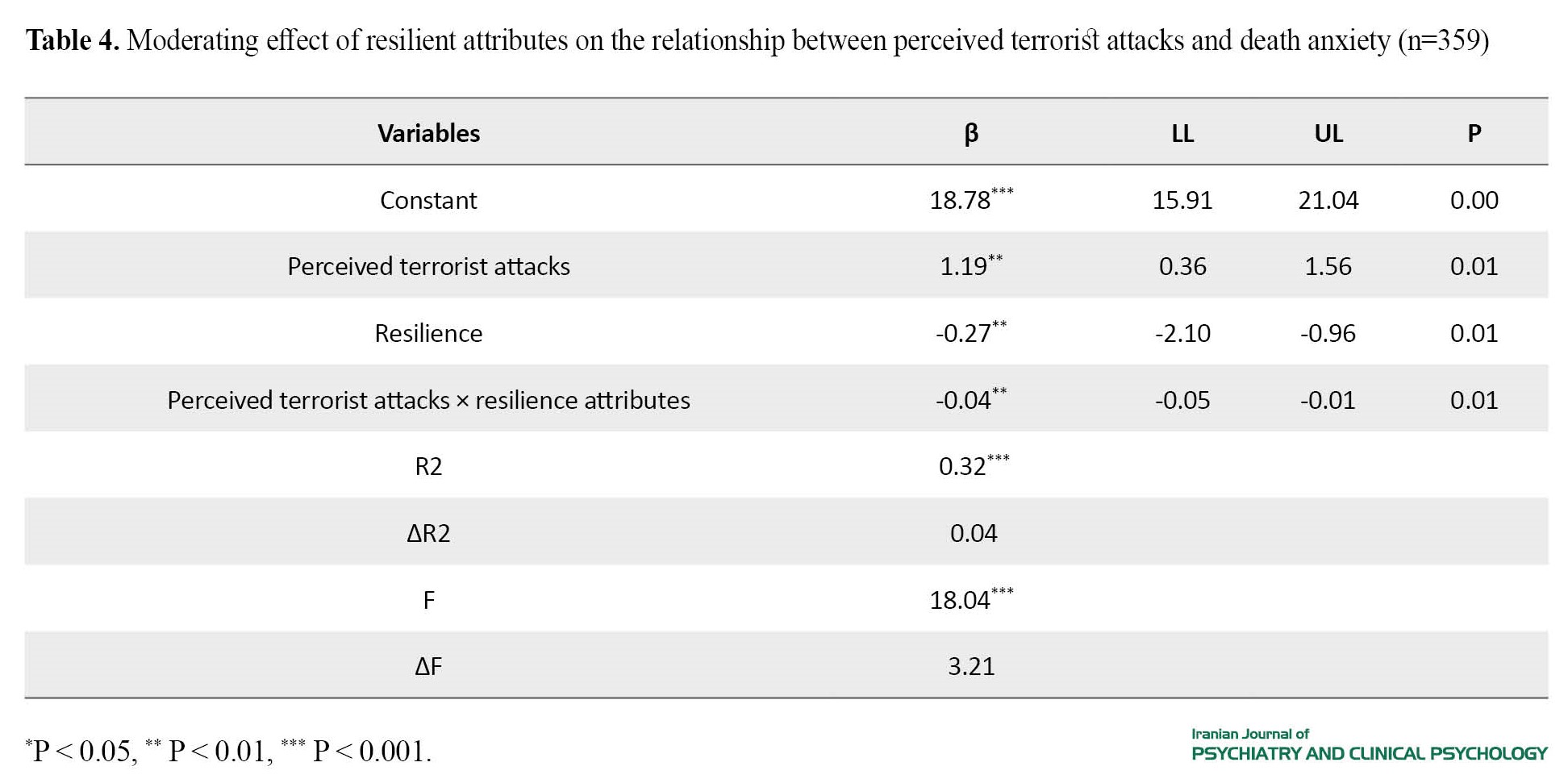

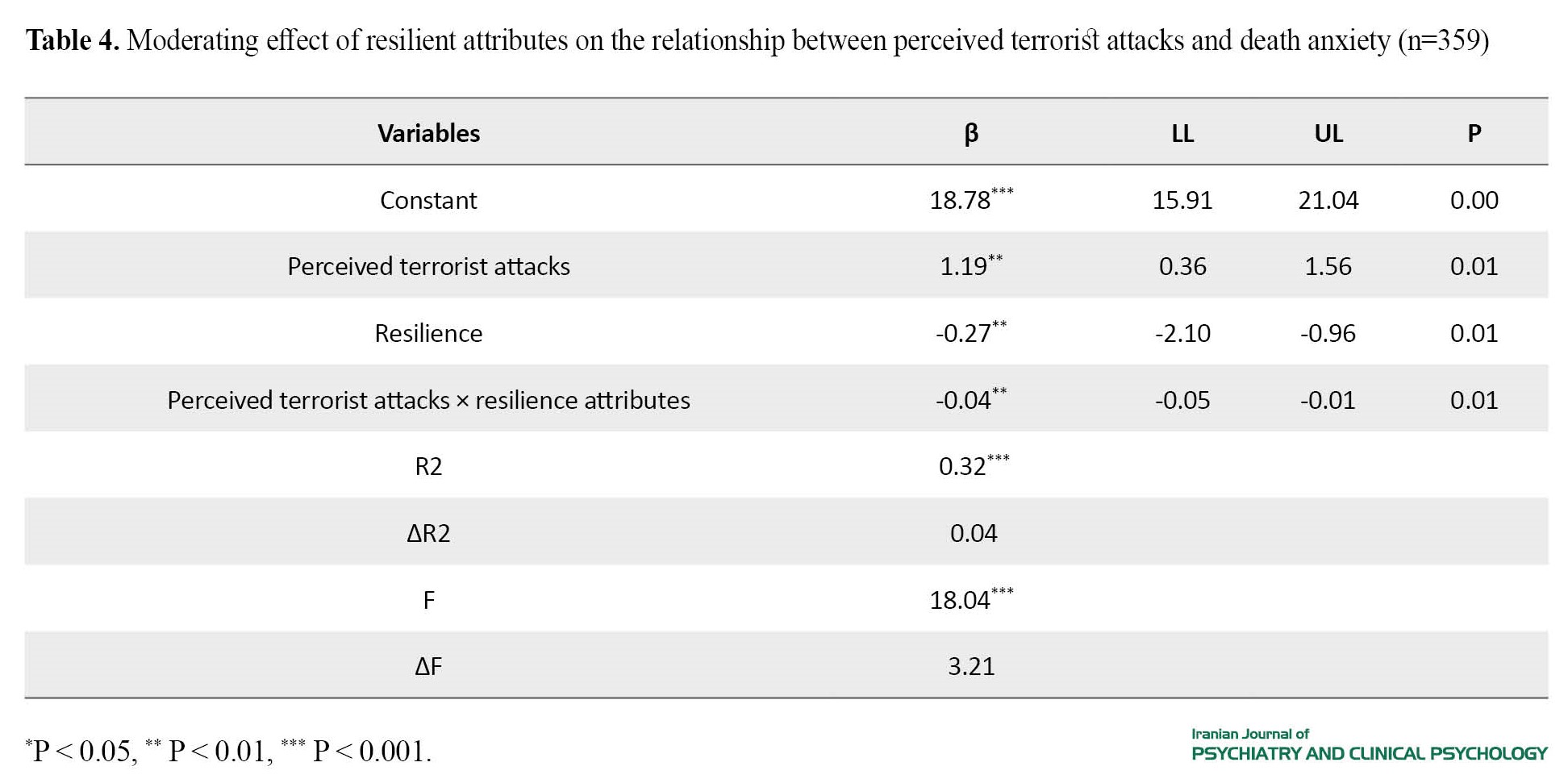

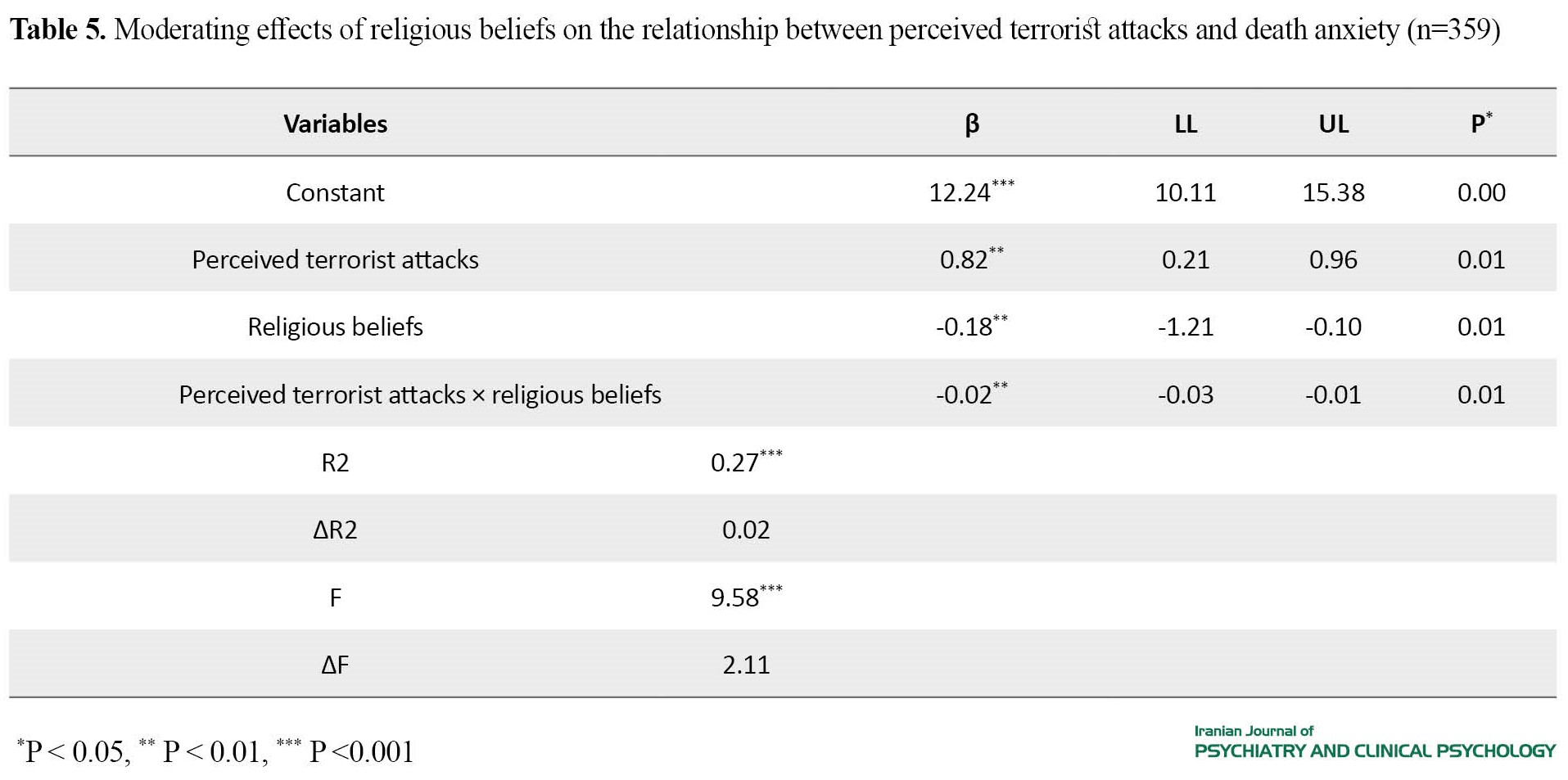

Table 4 demonstrates that the main effect of perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety is significantly positive (P<0.05).

The findings also show the significance (P<0.05) of the interaction effects of the moderator and the predictor (that is, resilience attributes and perceived terrorist attacks on the outcome variable which is the death anxiety in individuals).

The model graph reveals these results which are given as follows.

Figure 1 shows the interaction of resilience attributes and perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety. The graph demonstrates that the effect of resilience attributes is negative on perceived terrorist attacks in predicting death anxiety.

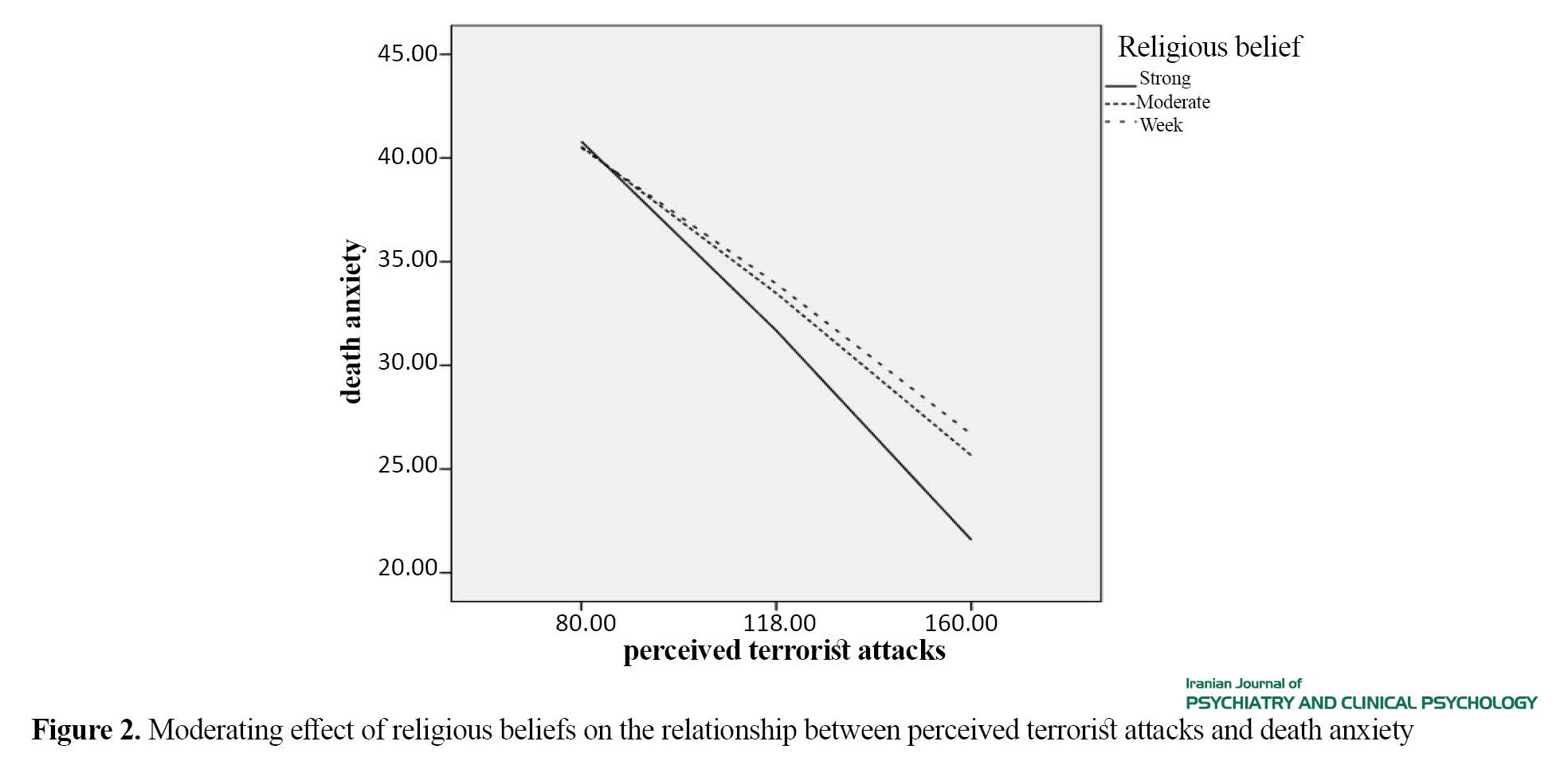

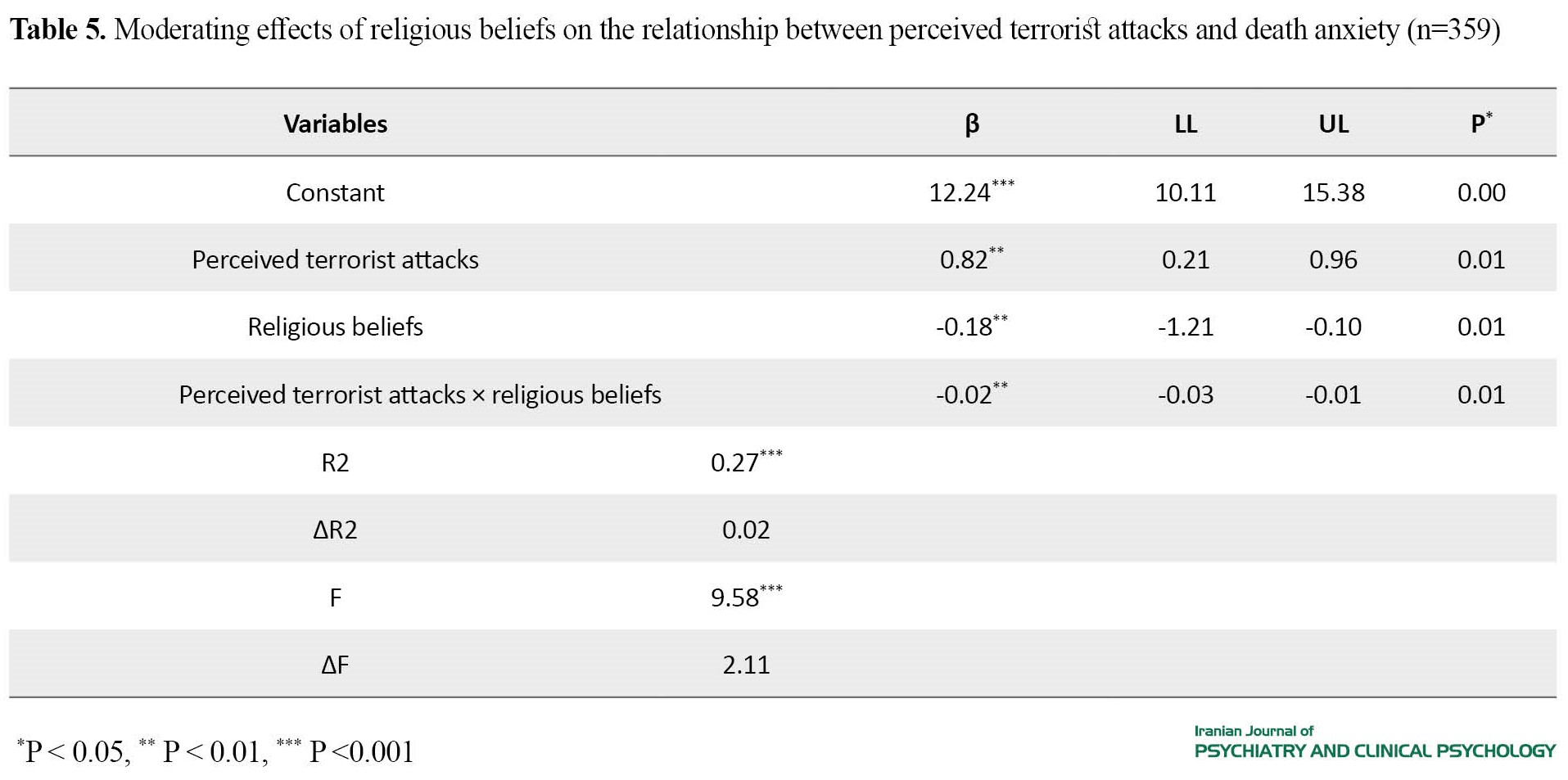

Table 4 demonstrates that the main effect of perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety is significantly positive (P<0.05). The findings also show the significance (P<0.05) of the interaction effects of the moderator and the predictor (that is, religious beliefs and perceived terrorist attacks on the outcome variable which is death anxiety in individuals).

In Figure 2, the graph reveals the interaction of religious beliefs and perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety. The graph demonstrates that the presence of strong religious beliefs decreases the impact of perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the association between the impact of perceived terrorist attacks, resilient attributes, and religious beliefs on death anxiety. Descriptive statistics were calculated and provided in Table 1. The results show that SD, kurtosis, and skewness of all scales and subscales are equal to or less than 1.00, suggesting consistencies of all the responses. The α coefficients of the scale indicate that all the instruments are reliable and valid. The results are consistent with previous studies [38, 39].

Table 2 shows the inter-scale correlation between directly and indirectly perceived terrorist attacks by individuals. Table 2 shows that perceived terrorist attacks and its dimension (dread, lack of control, and extent of exposure) are significantly positively related to death anxiety, but negatively related to resilience attributes, and religious beliefs in both directly and indirectly perceived individuals. On other hand, resilience attributes and religious beliefs are significantly positively related to each other but significantly negatively related to death anxiety. The results indicated that terrorist attacks, such as bomb blasts, suicidal attacks, use of violence, and so on increase the level of death anxiety in individuals whether they are directly exposed to these terrorist attacks or they perceive it from other sources, such as news bullets and so on. On the other hand, resilience attributes and religious beliefs weaken the impact of terrorist attacks by lowering the death anxiety among such individuals. The results are consistent with previous studies [9, 10, 12, 14]. The reason might be that individuals who are the victims of terrorist attacks may develop more resilience with time. because of living in a muslin society, they have strong beliefs in the hereafter and the Day of Judgment. These religious beliefs might reduce their anxiety related to death and destruction.

Table 3 shows the difference in studied variables among individuals who were directly exposed to terrorist attacks and also those who just perceived it through other sources. The results demonstrate that those who were the victims of perceived terrorist attacks scored lower on death anxiety but higher on resilience attributes and religious beliefs. These results are consistent with the previous studies, stating that the catastrophizing impact of terrorist attacks increases death anxiety [39, 40]. It was also found that resilience and religious beliefs are protective factors in reducing death anxiety resulting from terrorist attacks in directly exposed individuals [27]. Exposure to a terrorist threat causes physical harm and shatters one’s beliefs and faith about a safe world but at the same time increases the coping ability of people who face such terrorist attacks [26, 34]. People who believe in the existence of God experience lower death anxiety [30]. This indicated that coping, willpower, and belief in the existence of God and hereafter may reduce their fear of death.

For this reason, the moderation analysis was carried out on resilience attributes (Table 4) and religious beliefs (Table 5) for the relationship between perceived terrorist attacks and death anxiety.

The results showed that both resilience attributes and religious beliefs weaken the relationship between perceived terrorist attacks and death anxiety. The reason might be that resilience works as a factor of successful psychosocial adjustment and adaptation is associated with mental health and decreases the level of death anxiety and depression [3, 32, 41]. People who are catastrophized are more likely to experience death anxiety, but an increase in faith in religious beliefs and the life after belief may reduce their level of anxiety related to death and destruction [10, 17, 41]. Living in a stressful setting for a long period can reduce death anxiety by increasing the coping abilities of individuals [18].

Living with the heightened risk of a sudden, violent injury or death has greatly disrupted the established routines. At the individual level, the feeling of fear, anger, anxiety, and distress are generated. These reactions motivate residents to reorganize their daily activities in a way that may decrease their exposure to further attacks by strengthening their resilience attributes and religious belief about death and living hereafter [4]. However, resilient people with strong religious beliefs also confront difficult situations and instead of becoming overwhelmed by the threat of terrorism, they discover effective ways to cope with the situations, such as through friendship, volunteer work, and spending more time with their families. Therefore, they are less anxious and fearful about death [14, 42].

Study Limitations

The students and the management of Army Public School and the Bacha Khan University showed reluctance in data collection because of security reasons after the terrorist attacks. Accordingly, the samples of directly exposed individuals were limited in number.

The study had various limitations, for instance, the findings of this study are based on self-reported information provided by the participants that may offer biased responses.

Only two institutions where directly exposed individuals could be found were contacted. The cities of Baluchistan, Lahore, and Karachi are equally vulnerable and have remained the targets of terrorist attacks. Future studies may involve samples from other cities of Pakistan to compare directly exposed individuals in different cities of Pakistan.

Study Implications

This study is beneficial for society as it can establish interventions or counseling rehabilitation centers for the victims of terrorist attacks to reduce their fear and anxiety related to death. Participation in various activities will give them a sense of purpose, which will lead to optimism and self-efficacy. After analyzing the findings of this study, it will be helpful to run programs for building resilience in these stressful situations and offer preventive programs to the victims of developing posttraumatic stress disorder because of the stress resulting from terrorist activities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All the participants were informed in order to follow the ethical principles in all stages of research. They were assured that their information will be kept confidential.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I am thankful to Allah Almighty, who is the most merciful and beneficial Lord of all the creations, and the Holy Prophet (PBUH), whose blessings enabled me to perceive and pursue higher ideas of life and have given me the courage, insight, and knowledge to accomplish this research. I am highly grateful and indebted to my supervisor Dr. Nasreen Rafiq (Head of Department Applied Psychology Islamabad Model College for Girls Post Graduate F-7/2, Islamabad) who has become a life inspiration for me, and without her support, encouragement, and assistance, I was not able to complete this task.

References

Terrorism is one of the world’s biggest challenges nowadays and its causes and consequences are difficult to specify. It induces terror and fear in the public and causes people to be victimized both directly (physically) and indirectly (psychologically). Pakistan is included in countries where such cruel acts (suicide bombing, target killings, and serial bombing) occur almost regularly in the past few years. Researchers believe that in such situations, people may have a higher level of death anxiety. A terrorist attack is defined as the threatening or actual use of illegal force and violence by a nonstate actor to achieve a political, economic, religious, or social purpose through fear, compulsion, or intimidation. According to the global terrorism database (GTD), terrorism reached a new level after the attack on the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. This attack had Middle Eastern and European roots, and it has religious and secular dimensions.

Terrorism is defined as the deliberate acts of violence against civilians to fulfill some ideological, religious, or political goals [1]. Since September 11, 2011, the world has spent hundreds of billions of dollars on counterterrorism measures against 4 hijackings [2]. Terrorism is a very complex subject, and many researchers have shed light on it, maintaining that there are numerous reasons and causes involved in such acts. Terrorist attacks in Pakistan have taken 36 495 lives and injured 27 985 persons in recent years as a result of 3482 bombings and 281 suicide attacks [3].

Ethnicity, illiteracy, population growth, income inequality, high unemployment rate, inflation, poverty, high political instability, and injustice are the factors that contribute to terrorism in Pakistan [4, 5, 6]. Pakistan is playing its role as a front line against terrorism after 9/11. As a result, such measures are increasing day by day in the country. The psychological well-being of individuals is harmed because of these terrorist actions. According to some research conducted in Pakistan, terrorist activities have affected the mental health of people [5, 6, 7]. Terrorist attacks have an impact on people’s mental health as they get anxious, worried, and depressed as a result of such attacks. The majority of the time, people are emotionally upset and ill. And, given the recent wave of terrorism that has left people fearful for their safety as well as for their families, they do not consider themselves or their families safe and secure in this environment. They are also fearful about death and such uncertain fearful situations induce death anxiety among them. To address this problem, a collaborative and non-judgmental approach is important [8]. Terrorist attacks in Pakistan produce a huge and ongoing kind of insecurity among the public as this dread disturbs their routine life along with their financial setup [9].

Research on the public perceptions and the psychological impacts of terrorist attacks has increased in recent years in Western countries because of the occurrence of several high-profile incidences, such as the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the Madrid and London bombings of 2004 and 2005, respectively [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. According to the previous literature, the perceived impact of terrorist attacks includes 1) harming people physically during direct attacks, 2) illness and injury because of toxic substances released in the surrounding (e.g., bomb explosions), 3) disturbed daily life activities by causing secondary stressors (e.g., access to services, such as health care and transportation), 4) psychological distress to those who are directly and indirectly exposed to terrorism, and 5) damage to mental and physical health as a result of intensified fear response [15]. However, these studies have explored the effects of terrorism on mental health. No study has been conducted to investigate the impact of terrorist attacks on death anxiety among directly and indirectly perceived individuals. The present study aims to fill this gap using information from individuals who perceived terrorism from news content or other sources along with those who are the direct victim of terrorist attacks.

Anxiety is an emotion characterized by concerned thoughts, strained feelings, and bodily changes, such as increased blood pressure [16]. Anxiety has many types; one type is death anxiety. Death Anxiety is a psychological phenomenon defined as the dread of destruction, fear of life hereafter, and worries of becoming nothing at all [17]. Fear of death is not a single variable, rather it includes several aspects, such as the loss of individuality, loneliness, or isolation [18]. Studies indicated that constant and prolonged exposure to dreadful and threatening situations, such as terrorist activities, enhances the vulnerability of getting anxious about death [19]. A study was conducted on university students’ level of terrorism catastrophizing, perceived stress, and death anxiety [9]. The finding of this study indicated that terrorism catastrophizing and perceived stress were the considerable and significant predictors of death anxiety. Terrorism is an inevitable reality in the present situation, and the whole world is trapped in its brutal jaws of it. It has been found that constant and prolonged exposure to threatening and combat situations, such as terrorist activities, enhances the vulnerability to obliteration anxiety and fear of death [19].

Resilience is the ability to recover from illness or misfortune. The psychological meaning of resilience is the ability to cope with stressors of daily life activities. The term, resilience, is defined as the ability to recover or spring back [20]. Resilience is considered a set of attributes that help people overcome and successfully cope with adversity and danger [21]. Some researchers have found that repeated exposure to traumatic events can desensitize individuals, creating invulnerability to reduce psychological and physiological distress following future adversities by enhancing their coping ability [25]. Several factors increase resilience to traumatic situations, including the capacity to deal with trauma, mental and physical preparation for the trauma, and past experiences of successful and spontaneous recovery from trauma. Every individual has some degree of resilience while few may be more resilient to one kind of stress than others. In situations where terrorism has become prevalent, collective training, such as methods to cope with these threatening situations is common among people [22]. A study on male traffic police wardens (as the easy targets of terror attacks among security forces) in Lahore City, Pakistan, found a significant negative relationship between resilience and catastrophizing impact of terror attacks [23]. Exposure to a terrorist threat causes physical harm and shatters an individual’s belief and faith about a safe world; however, it simultaneously increases the coping ability of those who face such attacks [24]. Some researchers have found that death anxiety is a perceived inability to achieve major life ambitions and goals and a sense of regret. Death anxiety decreases the coping ability of an individual [25, 26, 15]. We need to educate people to cope with dreadful situations through resilience. This study explores the moderating role of resilience in dreadful situations, such as terrorist attacks. In the samples of Chinese patients, resilience was found to be a protective factor related to anxiety and depression and a protective factor during the pandemic situation [27].

Religion provides a basic framework for addressing and answering death and dying-related questions [18]. Religion indicates that individual differences in death anxiety are mostly caused by their religious belief, rituals, and attitudes. Religious beliefs are the mental representation of an attitude, positively oriented toward the likelihood of something being true [28], while religious behaviors are the rituals that are motivated by religious beliefs [29]. People who believe in the existence of God experience low death anxiety [30]. It is also considered one of the factors that enhances the individual’s coping ability by changing their perspective about life and hereafter and leads them toward a positive path by giving them knowledge about various topics, such as the purpose of life, the meaning of life, and reasons for their creation [31]. People who believe in the existence of God experience low death anxiety [30]. Several studies have reported a moderate relationship between religiosity and death anxiety among Muslim samples from outside the United States [32]. People who believe in the existence of God experience low death anxiety compared to non-believers [30]. A study was conducted to investigate the relationship between religious beliefs and resilience in academic students who had experienced any traumatic event [16]. The results indicated that the practice of religious beliefs improved resilience in students who were injured or witnessed these traumatic events [16]. Religious beliefs boost optimism, resilience, and hope, which reduce death anxiety [33]. Religious coping was revealed to be one of the most important predictors of death anxiety in the elderly [34].

A study was conducted to investigate the relationship between religious beliefs and resilience in students who experienced any traumatic event. The results of the study indicated that the practice of religious beliefs improved resilience in those students who were injured or witnessed these traumatic events [8]. Religious beliefs can provide support through the following ways: enhancing acceptance, endurance, and resilience as they generate peace, providing self-confidence and a sense of purpose, forgiveness toward the individual’s failures, self-giving, positive self-image, and preventing depression, fear, and anxiety [35].

Terrorism is an inevitable reality in the current world as numerous studies have been conducted concerning this subject in Western countries. Pakistan is also facing such terrible situations, however, people are continuing their normal routine life. Literature is scarce on related variables in Eastern countries. The present study will add to this topic’s literature for future researchers. Accordingly, religious beliefs are protective factors in reducing death anxiety resulting from terrorist attacks both directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

Study Objectives

This study aims to explore the following objectives:

To explore the perceived impact of terrorist attacks in terms of dread, lack of control, and extent of exposure to terrorist attacks on the experience of death anxiety among directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

To explore the moderating effect of resilience attributes and religious beliefs in the relationship between the perceived impact of terrorist attacks and the experience of death anxiety.

Methods

Study Samples

The samples were selected via convenience and purposive sampling techniques. We used the quantitative research method in the study. The samples consisted of 359 students, studying in schools, colleges, and universities of Islamabad City and Peshawar City, Pakistan. A total of 70 students were selected from the Army Public College and 89 students were selected from the Bacha Khan University as they were directly exposed to terrorist attacks. The participants for the indirectly exposed category were selected from educational institutions. A total of 50 students were selected from the Federal Medical and Dental College, 120 students from I.M.C.G (Postgraduate) F-7/2 Islamabad, and 30 students from L.M.C.B, G-10/4 Islamabad. Accordingly, the samples helped to compare the direct and perceived impact of terrorist attacks among students of different ages and different educational levels. The distribution of the sample in terms of age was 15-17 years (n=106) and 18-21 years (n=253). The mean age of the samples was 18.70 and the standard deviation (SD) was 2.59. The distribution of the participants in terms of the level of education is given as follows: F.A./F. Sc (n = 132), BA/B. Sc/BS/ BBA (n=152), and M.A/M. Sc/MS/ M. Phil/ M.B.B.S (n=76). Thus, the samples consisted of more participants currently studying their BA/B. Sc/BS.

Inclusion Criteria

The directly perceived individuals were those who were the victim of terrorist activities while those who perceived it through exposure to different social media sites, such as news content, YouTube, and so on were under the category of indirectly perceived individuals.

Exclusion Criteria

The samples in the intensive care unit or rehabilitation centers were not included in this study.

Study Instruments

Following are the four instruments that were used in the present study along with the demographic sheet.

Perceived Impact of Terrorist Attack Scale

This scale was developed by the author of the thesis by Ayesha Khan under the supervision of Dr. Nasreen Rafiq (2016). This questionnaire is based on the risk perception theory of Combs, Fischhoff, Slovic, Lichtenstein, and Read (1978). This questionnaire is in line with the aim of this study, which is to measure the perceived impact of terrorist attacks. The present scale is based on 4 factors of the author’s theory of risk perception: dread, lack of control, knowledge of risk, and the extent of exposure. A self-constructed scale of 27 items was developed from which 18 items were selected, based on the above factors. Then, they were divided into 3 dimensions: extent of exposure, lack of control, and dread. The participants responded to each dimension-related item on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (to a greater extent). Item 23 was inversely scored. At first, this scale was administered to a sample of 95 individuals to establish its psychometric properties and reported the reliability coefficient of α = 0.75 for the full scale.

Death Anxiety Scale

The death anxiety scale (DAS) is a self-report measure that is used in populations facing life-threatening illnesses [33]. DAS includes 15 items that are intended to be rated on a dichotomous scale (true/false) [21]. Higher scores represent a greater amount of fear and anxiety of death in the respondent. Good internal consistency of 0.76 was obtained with 31 participants through the Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 [7] which indicated that the scale is consistent and stable.

The Resilience Scale for Adults

The revised version of the resilience scale for adults (RSA) [37] is used in the present study. This version includes 33 items and 6 subscales, including 1) perception of self, 2) planned future, 3) social competence, 4) structured style, 5) family cohesion, and 6) social resources in which each item was positively stated. This scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of resilience and coping. The α coefficient of RSA is reported in previous studies to be 0.87 [37], indicating that the scale is valid and reliable.

Religiosity Questionnaire

The religiosity questionnaire [13] includes 34 items and 2 subscales, including religious behaviors and religious beliefs. The participants respond to each belief-related item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate strong religious behaviors and beliefs. The internal consistency for the scale was obtained at α = 0.81. Five items (8, 9, 13, 15, and 21) in the present questionnaire were kept negative to control the response bias [13].

Study Procedure

This study was conducted in different phases. At first, a self-constructed demographic sheet was developed. Then, different scales were selected to achieve the objectives of the study. The permission for using the instruments was obtained from the respective authors. Before completing the questionnaire, the educational authorities were contacted and permission for data collection was taken. Next, each participant provided their consent form. The students were briefly informed about the nature and purposes of the research, their anonymity, and the confidentiality of their information, along with their right to withdraw from the study at any point. The questionnaires were administered to the samples after obtaining their informed consent letters. The samples were selected via convenience and purposive sampling techniques. Almost 15 participants withdrew from the study because of privacy issues. A total of 411 questionnaires were collected from the participants. The students returned the completed questionnaires and the survey completion lasted approximately 30 min. The participants were also briefed about how they could inquire about the results of the present research by contacting the department. A total of 12 questionnaires were discarded because of the missing data.

Data Analysis and Results

After the data collection, the data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 23, and process macro. The data were subjected to statistical analyses according to the stated objectives. Mean, SD, and correlation coefficients were carried out on the variables to explore the perceived impacts of terrorist attacks on death anxiety in terms of dread, lack of control, and extent of exposure . The role of resilience attributes and religious beliefs as moderators were also observed.

Table 1 shows the mean, SD, α reliability, skewness, and kurtosis for each scale.

The results demonstrate that the α reliability coefficient of all scales is in the accepted range.

Table 2 shows the positive relationship between the perceived impacts of terrorism and its dimensions (dread, lack of control, exposure) on death anxiety among directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

The table also demonstrates that dread and death anxiety is significantly negatively related to resilient attributes and religious belief, whereas resilience attributes are positively related to religious belief in both directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

Table 3 shows the difference in the study variables among directly and indirectly perceived individuals.

The table indicates that individuals who were directly exposed to terrorist attacks scored higher on dread, resilience attributes, and religious beliefs but low on death anxiety compared to those who indirectly perceived terrorist attacks.

Moderating Effect of Resilience Attributes and Religious Beliefs for the Relationship Between Perceived Terrorist Attacks and Death Anxiety

The moderating effect of resilient attributes and religious beliefs was also determined for terrorist attacks in predicting death anxiety. The results obtained from the analysis are provided below.

Table 4 demonstrates that the main effect of perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety is significantly positive (P<0.05).

The findings also show the significance (P<0.05) of the interaction effects of the moderator and the predictor (that is, resilience attributes and perceived terrorist attacks on the outcome variable which is the death anxiety in individuals).

The model graph reveals these results which are given as follows.

Figure 1 shows the interaction of resilience attributes and perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety. The graph demonstrates that the effect of resilience attributes is negative on perceived terrorist attacks in predicting death anxiety.

Table 4 demonstrates that the main effect of perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety is significantly positive (P<0.05). The findings also show the significance (P<0.05) of the interaction effects of the moderator and the predictor (that is, religious beliefs and perceived terrorist attacks on the outcome variable which is death anxiety in individuals).

In Figure 2, the graph reveals the interaction of religious beliefs and perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety. The graph demonstrates that the presence of strong religious beliefs decreases the impact of perceived terrorist attacks on death anxiety.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the association between the impact of perceived terrorist attacks, resilient attributes, and religious beliefs on death anxiety. Descriptive statistics were calculated and provided in Table 1. The results show that SD, kurtosis, and skewness of all scales and subscales are equal to or less than 1.00, suggesting consistencies of all the responses. The α coefficients of the scale indicate that all the instruments are reliable and valid. The results are consistent with previous studies [38, 39].

Table 2 shows the inter-scale correlation between directly and indirectly perceived terrorist attacks by individuals. Table 2 shows that perceived terrorist attacks and its dimension (dread, lack of control, and extent of exposure) are significantly positively related to death anxiety, but negatively related to resilience attributes, and religious beliefs in both directly and indirectly perceived individuals. On other hand, resilience attributes and religious beliefs are significantly positively related to each other but significantly negatively related to death anxiety. The results indicated that terrorist attacks, such as bomb blasts, suicidal attacks, use of violence, and so on increase the level of death anxiety in individuals whether they are directly exposed to these terrorist attacks or they perceive it from other sources, such as news bullets and so on. On the other hand, resilience attributes and religious beliefs weaken the impact of terrorist attacks by lowering the death anxiety among such individuals. The results are consistent with previous studies [9, 10, 12, 14]. The reason might be that individuals who are the victims of terrorist attacks may develop more resilience with time. because of living in a muslin society, they have strong beliefs in the hereafter and the Day of Judgment. These religious beliefs might reduce their anxiety related to death and destruction.

Table 3 shows the difference in studied variables among individuals who were directly exposed to terrorist attacks and also those who just perceived it through other sources. The results demonstrate that those who were the victims of perceived terrorist attacks scored lower on death anxiety but higher on resilience attributes and religious beliefs. These results are consistent with the previous studies, stating that the catastrophizing impact of terrorist attacks increases death anxiety [39, 40]. It was also found that resilience and religious beliefs are protective factors in reducing death anxiety resulting from terrorist attacks in directly exposed individuals [27]. Exposure to a terrorist threat causes physical harm and shatters one’s beliefs and faith about a safe world but at the same time increases the coping ability of people who face such terrorist attacks [26, 34]. People who believe in the existence of God experience lower death anxiety [30]. This indicated that coping, willpower, and belief in the existence of God and hereafter may reduce their fear of death.

For this reason, the moderation analysis was carried out on resilience attributes (Table 4) and religious beliefs (Table 5) for the relationship between perceived terrorist attacks and death anxiety.

The results showed that both resilience attributes and religious beliefs weaken the relationship between perceived terrorist attacks and death anxiety. The reason might be that resilience works as a factor of successful psychosocial adjustment and adaptation is associated with mental health and decreases the level of death anxiety and depression [3, 32, 41]. People who are catastrophized are more likely to experience death anxiety, but an increase in faith in religious beliefs and the life after belief may reduce their level of anxiety related to death and destruction [10, 17, 41]. Living in a stressful setting for a long period can reduce death anxiety by increasing the coping abilities of individuals [18].

Living with the heightened risk of a sudden, violent injury or death has greatly disrupted the established routines. At the individual level, the feeling of fear, anger, anxiety, and distress are generated. These reactions motivate residents to reorganize their daily activities in a way that may decrease their exposure to further attacks by strengthening their resilience attributes and religious belief about death and living hereafter [4]. However, resilient people with strong religious beliefs also confront difficult situations and instead of becoming overwhelmed by the threat of terrorism, they discover effective ways to cope with the situations, such as through friendship, volunteer work, and spending more time with their families. Therefore, they are less anxious and fearful about death [14, 42].

Study Limitations

The students and the management of Army Public School and the Bacha Khan University showed reluctance in data collection because of security reasons after the terrorist attacks. Accordingly, the samples of directly exposed individuals were limited in number.

The study had various limitations, for instance, the findings of this study are based on self-reported information provided by the participants that may offer biased responses.

Only two institutions where directly exposed individuals could be found were contacted. The cities of Baluchistan, Lahore, and Karachi are equally vulnerable and have remained the targets of terrorist attacks. Future studies may involve samples from other cities of Pakistan to compare directly exposed individuals in different cities of Pakistan.

Study Implications

This study is beneficial for society as it can establish interventions or counseling rehabilitation centers for the victims of terrorist attacks to reduce their fear and anxiety related to death. Participation in various activities will give them a sense of purpose, which will lead to optimism and self-efficacy. After analyzing the findings of this study, it will be helpful to run programs for building resilience in these stressful situations and offer preventive programs to the victims of developing posttraumatic stress disorder because of the stress resulting from terrorist activities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All the participants were informed in order to follow the ethical principles in all stages of research. They were assured that their information will be kept confidential.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I am thankful to Allah Almighty, who is the most merciful and beneficial Lord of all the creations, and the Holy Prophet (PBUH), whose blessings enabled me to perceive and pursue higher ideas of life and have given me the courage, insight, and knowledge to accomplish this research. I am highly grateful and indebted to my supervisor Dr. Nasreen Rafiq (Head of Department Applied Psychology Islamabad Model College for Girls Post Graduate F-7/2, Islamabad) who has become a life inspiration for me, and without her support, encouragement, and assistance, I was not able to complete this task.

References

- Borum R. Understanding terrorist psychology. In:Silke A, editor. The psychology of counter-terrorism. London: Routledge; 2010. [Link]

- Depaola SJ, Griffin M, Young JR, Neimeyer RA. Death anxiety and attitudes toward the elderly among older adults: The role of gender and ethnicity. Death Studies. 2003; 27(4):335-54. [DOI:10.1080/07481180302904] [PMID]

- Khan A, Estrada MAR, Yusof Z. How terrorism affects the economic performance? The case of Pakistan. Quality & Quantity. 2016; 50(2):867-83. [DOI:10.1007/s11135-015-0179-z]

- Khan AM, Sarhandi I, Hussain J, Iqbal S, Taj R, . Impact of terrorism on mental health. Annals of Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences. 2012; 8(1):46-9. [Link]

- Jones DM, Smith ML. The changing security agenda in Southeast Asia: globalization, new terror, and the delusions of regionalism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 2001; 24(4):271-88. [DOI:10.1080/10576100117412]

- Slovic P. The perception of risk. In: Sternberg R, Fiske S, Foss D, editors. Scientists making a difference: One hundred eminent behavioral and brain scientists talk about their most important contributions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9781316422250.040]

- Malik OF, Schat AC, Raziq MM, Shahzad A, Khan M. Relationships between perceived risk of terrorism, fear, and avoidance behaviors among Pakistani university students: A multigroup study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2018; 124:39-44. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.044]

- Howie L. There is nothing to fear but fear itself (and terrorists): Public perception, terrorism and the workplace. Paper presented at: the Social Change in the 21st Century Conference. 28 October 2005; Queensland, Australia. [Link]

- Mosavel M, Ahmed R, Ports KA, Simon C. South African, urban youth narratives: Resilience within community. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2015; 20(2):245-55. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fischhoff B, Slovic P, Lichtenstein S, Read S, Combs B. How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sciences. 1978; 9:127-52. [DOI:10.1007/BF00143739]

- Haq IU, Mahmud N, Zainab B, Azeem MU, Anwar F. Combine effects of fear of terrorism and psychological capital on job outcomes. Academy of Management Proceedings. 2016; 1:16026. [DOI:10.5465/ambpp.2016.16026abstract]

- Miller RL, Mulligan RD. Terror management: The effects of mortality salience and locus of control on risk-taking behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002; 33(7):1203-14. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00009-0]

- Rafiq N, Shehzadi I. Religiosity [MA thesis]. Islamabad: Islamabad Model College for Girls; 2013.

- Vishkin A, Tamir M. Fear not: Religion and emotion regulation in coping with existential concerns. In: Vail KE, Routledge C, editors. The science of religion, spirituality, and existentialism. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2020. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-817204-9.00023-8]

- Shahbaz M, Shabbir MS, Malik MN, Wolters ME. An analysis of a causal relationship between economic growth and terrorism in Pakistan. Economic Modeling. 2013; 35:21-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.06.031]

- Ismail A, Amjad S. Determinants of terrorism in Pakistan: An empirical investigation. Economic Modeling. 2014; 37:320-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.11.012]

- Javanmard GH. Religious beliefs and resilience in academic students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 84:744-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.638]

- Davydov DM, Stewart R, Ritchie K, Chaudieu I. Resilience and mental health. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010; 30(1):479-95. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003] [PMID]

- Mehmood S. Terrorism and the macroeconomy: Evidence from Pakistan. Defence and Peace Economics. 2014; 25(5):509-34. [DOI:10.1080/10242694.2013.793529]

- Connor KM. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC. Depression and Anxiety. 2003; 18(2):76-82. [DOI:10.1002/da.10113] [PMID]

- Cyrulnik B. Resilience: How your inner strength can set you free from the past. London: Penguin; 2009. [Link]

- US Department of Defense. The Dictionary of Military Terms. Skyhorse Publishing Inc.; 2009.

- Goleman D. Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Learning. London: Bloomsbury; 1996. [Link]

- Vázquez C, Pérez-Sales P, Hervás G. Positive effects of terrorism and posttraumatic growth: An individual and community perspective. In: Joseph S, Linley A, editors. Trauma, recovery, and growth: positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress. New York: Wiley; 2008. [DOI:10.1002/9781118269718.ch4]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006; 256(3):174-86. [DOI:10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lau RW, Cheng ST. Gratitude lessens death anxiety. European Journal of Ageing. 2011; 8(3):169. [DOI:10.1007/s10433-011-0195-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lehto RH, Stein KF. Death anxiety: An analysis of an evolving concept. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2009; 23(1):23-41. [DOI:10.1891/1541-6577.23.1.23] [PMID]

- Sargent R, Brooks DJ. Terrorism in Australia: A psychometric study into the Western Australian public perception of terrorism. Paper presented at: 3rd Australian Security and Intelligence Conference. 30th November 2010; Perth, Australia. [Link]

- Fair CC, Malhotra N, Shapiro JN. Faith or doctrine? Religion and support for political violence in Pakistan. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2012; 76(4):688-720. [DOI:10.1093/poq/nfs053]

- Clore GL, Gasper K, Garvin E. Affect as information. In: Forgas JP, editor. Handbook of affect and social cognition. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis; 2012. [Link]

- Enders W, Sandler T. Distribution of transnational terrorism among countries by income class and geography after 9/11. International Studies Quarterly. 2006; 50(2):367-93. [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00406.x]

- Nayab R, Kamal A. Terrorism catastrophizing, perceived stress and death anxiety among university students. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010; 8(2):132-44. [Link]

- Crawford E, Wright MO, Masten AS. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. 2006.

- Bakan AB, Arli SK, Yıldız M. Relationship between religious orientation and death anxiety in elderly individuals. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019; 58(6):2241-50. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-019-00917-4] [PMID]

- Millstein SG, Halpern-Felsher BL. Perceptions of risk and vulnerability. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002; 31(1 Suppl):10-27. [DOI:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00412-3] [PMID]

- Templer DI. The construction and validation of a death anxiety scale. The Journal of General Psychology. 1970; 82(2d Half):165-77. [DOI:10.1080/00221309.1970.9920634] [PMID]

- Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2003; 12(2):65-76. [DOI:10.1002/mpr.143] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Peterson M, Hasker W, Reichenbach B, Basinger D. Reason and religious belief: An introduction to the philosophy of religion. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Link]

- Syed SH, Saeed L, Martin RP. Causes and incentives for terrorism in Pakistan. Journal of Applied Security Research. 2015; 10(2):181-206. [DOI:10.1080/19361610.2015.1004606]

- Cheung-Blunden V, Blunden B. Paving the road to war with group membership, appraisal antecedents, and anger. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression. 2008; 34(2):175-89. [DOI:10.1002/ab.20234] [PMID]

- Azeem F, Naz MA. Resilience, death anxiety, and depression among institutionalized and non-institutionalized elderly. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 2015; 30(1) 111-30. [Link]

- Vernberg EM, Varela RE. Posttraumatic stress disorder: A developmental perspective. In Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [DOI:10.1093/med:psych/9780195123630.003.0017]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2021/09/22 | Accepted: 2022/08/6 | Published: 2023/04/1

Received: 2021/09/22 | Accepted: 2022/08/6 | Published: 2023/04/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |