Mon, Sep 1, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 23, Issue 4 (Winter 2018)

IJPCP 2018, 23(4): 466-479 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mahmood Alilou M, Bakhshipour Roudsari A, Nasiri M. Structural Relationships Between Behavioral Brain Systems, Disgust Sensitivity, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. IJPCP 2018; 23 (4) :466-479

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2592-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2592-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran ,E-mail: mohammad.nasiritb@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran ,

Keywords: Behavioral brain systems, Disgust sensitivity, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Structural equation modeling

Full-Text [PDF 2995 kb]

(3763 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (9255 Views)

References

[1]Mataix-Cols D, Do Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF. A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005; 162(2):228-38. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.228

[2]Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry [N. Poorafkari Persian trans]. Tehran: Shahr Ab; 2009.

[3]American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

[4]Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system (Oxford psychology series). New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

[5]Matthews G, Gilliland K. The personality theories of HJ. Eysenck and JA. Gray: A comparative review. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999; 26(4):583–626. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00158-5

[6]Gray JA. Framework for taxonomy of psychiatric disorders. In: van Goozen SHM, Van de Poll NE, Sergeant JA, Van Goozen SHM, editors. Emotions: Essays on Emotion Theory. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 1994.

[7]Meyer B, Johnson SL, Winters R. Responsiveness to threat and incentive in bipolar disorder: Relations of the BIS/BAS scales with symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001; 23(3):133-43. doi: 10.1023/a:1010929402770

[8]Gray JA. Neural systems, emotion and personality. In: Madden J, editor. Neurobiology of Learning, Emotion and Affect. New York: Raven Press; 1991.

[9]Muris P, Meesters C, Spinder M. Relationships between child-and parent-reported behavioural inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression in normal adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003; 34(5):759-71. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00069-7

[10]Saxena S, Rauch SL. Functional neuroimaging and the neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000; 23(3):563-86. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70181-7

[11]Baxter LR, Schwartz JM, Bergman KS, Szuba MP, Guze BH, Mazziotta JC, et al. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992; 49(9):681-9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090009002

[12]Gray JA. Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cognition & Emotion. 1990; 4(3):269-88. doi: 10.1080/02699939008410799

[13]Bijttebier P, Beck I, Claes L, Vandereycken W. Gray's Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory as a framework for research on personality–psychopathology associations. Clinical psychology review. 2009; 29(5):421-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.002

[14]Berger U, Anaki D. The behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) mediates major aspects of the relationship between disgust and OCD symptomology. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2014; 3(3):249-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.06.004

[15]Olatunji BO, Haidt J, McKay D, David B. Core, animal reminder, and contamination disgust: Three kinds of disgust with distinct personality, behavioral, physiological, and clinical correlates. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008; 42(5):1243–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.009

[16]Oaten M, Stevenson RJ, Case TI. Disgust as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Psychological Bulletin. 2009; 135(2):303–21. doi: 10.1037/a0014823

[17]Cisler JM, Olatunji BO, Sawchuk CN, Lohr JM. Specificity of emotional maintenance processes among contamination fears and blood–injection–injury fears. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008; 22(5):915–23. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.006

[18]Berle D, Starcevic V, Brakoulias V, Sammut P, Milicevic D, Hannan A, et al. Disgust propensity in obsessive–compulsive disorder: Cross-sectional and prospective relationships. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2012; 43(1):656–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.002

[19]Olatunji BO, Ebesutani C, David B, Fan Q, McGrath PB. Disgust proneness and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in a clinical sample: Structural differentiation from negative affect. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011; 25(7):932–8. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.006

[20]Coles ME, Schofield CA, Pietrefesa AS. Behavioral inhibition and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006; 20(8):1118–32. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.003

[21]Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2010.

[22]Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994; 67(2):319–33. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319

[23]Poythress NG, Skeem JL, Weir J, Lilienfeld SO, Douglas KS, Edens JF, et al. Psychometric properties of Carver and White’s (1994) BIS/BAS scales in a large sample of offenders. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008; 45(8):732–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.021

[24]Mohammadi N. [The psychometric properties of the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and Behavioral Activation System (BAS) scales among students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology & Personality. 2008; 1(28):61-68

[25]Haidt J, McCauley C, Rozin P. Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994; 16(5):701–13. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7

[26]Karsazi H, Nasiri M, Hashemi-nosratabad T. [Factor analysis and evaluation of internal structure of disgust sensitivity scale (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017; 8(4):49-60.

[27]Mohammadi A, Zamani R, Ladan F. [Validation of the Persian version of the obsessive-compulsive inventory-revised in a student sample (Persian)]. Psychological Research. 2008; 11(1-2):66-78.

[28]Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8.80 for Windows [Computer software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2006.

[29]Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988; 103(3):411–23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

[30]Chou CP, Bentler PM. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, California; 1995.

[31]Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999; 6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

[32]Bentler PM. EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, California: Multivariate Software; 1995.

[33]Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008; 40(3):879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879

[34]Fullana MA, Mataix-Cols D, Caseras X, Alonso P, Manuel Menchón J, Vallejo J, et al. High sensitivity to punishment and low impulsivity in obsessive-compulsive patients with hoarding symptoms. Psychiatry Research. 2004; 129(1):21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.02.017

[35]Kort S. Autistic traits in hoarding disorder: a comparative study between patients with hoarding disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder [MSc. thesis]. Utrecht: Utrecht University; 2012.

[36]Corr PJ. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity theory: Tests of the joint subsystems hypothesis of anxiety and impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002; 33(4):511–32. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(01)00170-2

[37]Sellbom M, Ben-Porath YS, Bagby RM. On the hierarchical structure of mood and anxiety disorders: Confirmatory evidence and elaboration of a model of temperament markers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008; 117(3):576–90. doi: 10.1037/a0012536

Full-Text: (9218 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is characterized by the world health organization as a major cause of mental disturbance. Biological approach is one of the viewpoints in the field of etiology of psychological disorders, especially the OCD. In this regard, Gray and McNaughton’s reinforcement sensitivity theory is one of the most important theories investigating the biological basis of psychological disorders and personality. Based on this theory, Gray [6] raised the notion that psychiatric disorders are the result of a dysfunction, either in brain-Behavioral Activation System (BAS) or in brain-Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS). Losing the interaction between the two systems can also result in a similar outcome.

Although there are definite direct relationships between BAS sensitivity, BIS sensitivity, and mental disorders, evidence suggests that these direct relationships can only be a partial explanation for these relationships. Hence, intermediary mechanisms such as disgust sensitivity have been proposed for a better understanding of the relationship between brain-behavioral systems and OCD. Disgust as a negative and inclusive emotion involves a feeling of intense hatred and reluctance, which encompasses different physiological, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. Given the fact that previous research directly investigated the relationships between these variables, the more important issue is to rearrange these variables in a more structured model that can accurately explain the relationships between these variables. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to test the structural relationships between brain-behavioral systems, disgust sensitivity, and OCD.

2. Method

The present study is a fundamental type and of a descriptive-correlational type in terms of data collection. Considering the minimum sample size required when the variables of the model (in the hypothesized model of the present study, 15 variables) ranges from 10 to 15, the sample size should be between 200 and 400 [21]. Therefore, the sample size of this study was equal to 340 subjects. To choose the subjects, firstly, using a cluster sampling method, four colleges (including human sciences, technical, basic sciences and agriculture) were randomly selected. Then from each college, a number of students were randomly selected to include them in the research. To test the research hypotheses, the collected data were analyzed using SPSS 22 and LISREL 8.85 software. [28]. The fitness of the hypothesized model was assessed using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) method. The data analysis was performed using the two-step approach of Anderson & Gerbing [29] as follows: in the first step, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to assess the fitness of the measurement model, and in the second step, SEM was employed to assess the hypothesized structural model.

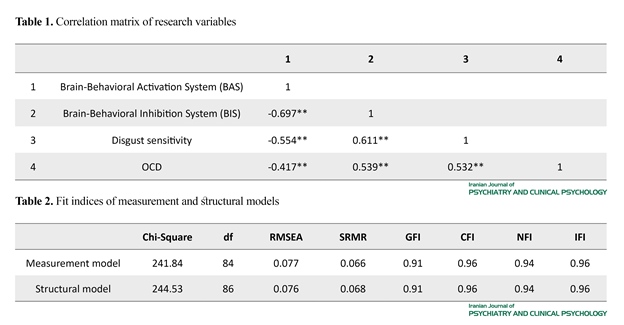

3. Results

The matrix of correlation coefficients between the variables of the research is shown in Table 1. As the content of the table shows, the correlations are significant (-0.697≥r≥0.611). The measurement model specifies the relationship between the observed and latent variables. The evaluation of the model was done using CFA method. The fit indices of the measurement model (Table 2) show a satisfactory fitness for this model. Therefore, the observed variables are capable of operating the latent variables.

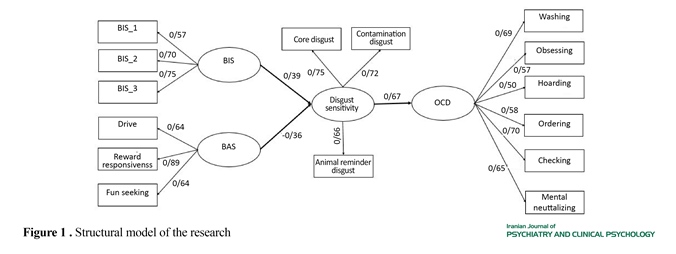

In addition, assessing the structural model via the SEM method revealed that all the fit indices of the hypothesized model were within the appropriate fitness range. The fit indices for this model are shown in Table 2. Figure 1 depicts the hypothetical structural model with its standard coefficients. As can be seen from Figure 1, the brain-Behavioral Activation System (BAS) and the brain-Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) as exogenous variables have an effect on the disgust sensitivity with a standard coefficient of -0.36 and -0.39, respectively. In addition, disgust sensitivity affects OCD with a standard coefficient of 0.67.

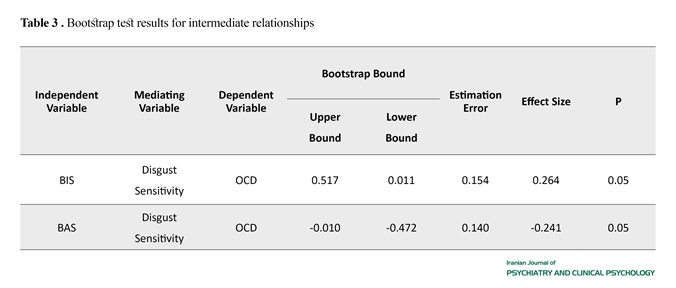

In the current study, the Bootstrap test was employed to evaluate the intermediate relationships. In this method,

1. Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is characterized by the world health organization as a major cause of mental disturbance. Biological approach is one of the viewpoints in the field of etiology of psychological disorders, especially the OCD. In this regard, Gray and McNaughton’s reinforcement sensitivity theory is one of the most important theories investigating the biological basis of psychological disorders and personality. Based on this theory, Gray [6] raised the notion that psychiatric disorders are the result of a dysfunction, either in brain-Behavioral Activation System (BAS) or in brain-Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS). Losing the interaction between the two systems can also result in a similar outcome.

Although there are definite direct relationships between BAS sensitivity, BIS sensitivity, and mental disorders, evidence suggests that these direct relationships can only be a partial explanation for these relationships. Hence, intermediary mechanisms such as disgust sensitivity have been proposed for a better understanding of the relationship between brain-behavioral systems and OCD. Disgust as a negative and inclusive emotion involves a feeling of intense hatred and reluctance, which encompasses different physiological, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. Given the fact that previous research directly investigated the relationships between these variables, the more important issue is to rearrange these variables in a more structured model that can accurately explain the relationships between these variables. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to test the structural relationships between brain-behavioral systems, disgust sensitivity, and OCD.

2. Method

The present study is a fundamental type and of a descriptive-correlational type in terms of data collection. Considering the minimum sample size required when the variables of the model (in the hypothesized model of the present study, 15 variables) ranges from 10 to 15, the sample size should be between 200 and 400 [21]. Therefore, the sample size of this study was equal to 340 subjects. To choose the subjects, firstly, using a cluster sampling method, four colleges (including human sciences, technical, basic sciences and agriculture) were randomly selected. Then from each college, a number of students were randomly selected to include them in the research. To test the research hypotheses, the collected data were analyzed using SPSS 22 and LISREL 8.85 software. [28]. The fitness of the hypothesized model was assessed using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) method. The data analysis was performed using the two-step approach of Anderson & Gerbing [29] as follows: in the first step, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to assess the fitness of the measurement model, and in the second step, SEM was employed to assess the hypothesized structural model.

3. Results

The matrix of correlation coefficients between the variables of the research is shown in Table 1. As the content of the table shows, the correlations are significant (-0.697≥r≥0.611). The measurement model specifies the relationship between the observed and latent variables. The evaluation of the model was done using CFA method. The fit indices of the measurement model (Table 2) show a satisfactory fitness for this model. Therefore, the observed variables are capable of operating the latent variables.

In addition, assessing the structural model via the SEM method revealed that all the fit indices of the hypothesized model were within the appropriate fitness range. The fit indices for this model are shown in Table 2. Figure 1 depicts the hypothetical structural model with its standard coefficients. As can be seen from Figure 1, the brain-Behavioral Activation System (BAS) and the brain-Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) as exogenous variables have an effect on the disgust sensitivity with a standard coefficient of -0.36 and -0.39, respectively. In addition, disgust sensitivity affects OCD with a standard coefficient of 0.67.

In the current study, the Bootstrap test was employed to evaluate the intermediate relationships. In this method,

if the upper and lower limits of this test are either positive or negative, and zero is not between these two limits, then the indirect causal path will be significant. Table 3 presents the results of this test.

4. Discussion

The present study, using a hypothetical structural model, tested the relationships between OCD, BIS and BAS, while the mediating role of disgust sensitivity was taken into account. As assumed, the findings supported a model in which the high BIS sensitivity and the low BAS sensitivity, due to the mediating role of disgust sensitivity, led to an escalation in the symptoms of OCD. The findings of this study signified that BIS and BAS as two biological traits of personality, with a mediating role of disgust sensitivity, have positive and negative effects, respectively on symptoms of OCD. In accordance with the findings of this study, research evidence suggests that BIS and BAS which show themselves as emotional styles are a major risk factor for emotional disturbances. Moreover, the unusual sensitivity of these systems provides readiness and vulnerability against the various kinds of psychiatric pathology [7] so that BAS and BIS can explain a wide range of disorders.

Olatunji et al. (2015) [15], who investigated the relationships between several personality factors and disgust, showed that the BIS is strongly correlated with disgust. Researchers believe that the relationship between BIS and disgust indicates that disgust usually serves as a regulator for aversive motivations. In particular, as disgust is usually associated with a negative stimulus, and since the BIS acts as an independent functional system that regulates behavior and motivation in response to annoying situations, the BIS’s sense of disgust may serve as a warning against the occurring upcoming punishment. In other words, disgust is considered a negative and annoying event, which is subsequently used by the BIS to respond to and regulate future behaviors and motivations.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

4. Discussion

The present study, using a hypothetical structural model, tested the relationships between OCD, BIS and BAS, while the mediating role of disgust sensitivity was taken into account. As assumed, the findings supported a model in which the high BIS sensitivity and the low BAS sensitivity, due to the mediating role of disgust sensitivity, led to an escalation in the symptoms of OCD. The findings of this study signified that BIS and BAS as two biological traits of personality, with a mediating role of disgust sensitivity, have positive and negative effects, respectively on symptoms of OCD. In accordance with the findings of this study, research evidence suggests that BIS and BAS which show themselves as emotional styles are a major risk factor for emotional disturbances. Moreover, the unusual sensitivity of these systems provides readiness and vulnerability against the various kinds of psychiatric pathology [7] so that BAS and BIS can explain a wide range of disorders.

Olatunji et al. (2015) [15], who investigated the relationships between several personality factors and disgust, showed that the BIS is strongly correlated with disgust. Researchers believe that the relationship between BIS and disgust indicates that disgust usually serves as a regulator for aversive motivations. In particular, as disgust is usually associated with a negative stimulus, and since the BIS acts as an independent functional system that regulates behavior and motivation in response to annoying situations, the BIS’s sense of disgust may serve as a warning against the occurring upcoming punishment. In other words, disgust is considered a negative and annoying event, which is subsequently used by the BIS to respond to and regulate future behaviors and motivations.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]Mataix-Cols D, Do Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF. A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005; 162(2):228-38. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.228

[2]Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry [N. Poorafkari Persian trans]. Tehran: Shahr Ab; 2009.

[3]American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

[4]Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system (Oxford psychology series). New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

[5]Matthews G, Gilliland K. The personality theories of HJ. Eysenck and JA. Gray: A comparative review. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999; 26(4):583–626. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00158-5

[6]Gray JA. Framework for taxonomy of psychiatric disorders. In: van Goozen SHM, Van de Poll NE, Sergeant JA, Van Goozen SHM, editors. Emotions: Essays on Emotion Theory. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 1994.

[7]Meyer B, Johnson SL, Winters R. Responsiveness to threat and incentive in bipolar disorder: Relations of the BIS/BAS scales with symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001; 23(3):133-43. doi: 10.1023/a:1010929402770

[8]Gray JA. Neural systems, emotion and personality. In: Madden J, editor. Neurobiology of Learning, Emotion and Affect. New York: Raven Press; 1991.

[9]Muris P, Meesters C, Spinder M. Relationships between child-and parent-reported behavioural inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression in normal adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003; 34(5):759-71. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00069-7

[10]Saxena S, Rauch SL. Functional neuroimaging and the neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000; 23(3):563-86. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70181-7

[11]Baxter LR, Schwartz JM, Bergman KS, Szuba MP, Guze BH, Mazziotta JC, et al. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992; 49(9):681-9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090009002

[12]Gray JA. Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cognition & Emotion. 1990; 4(3):269-88. doi: 10.1080/02699939008410799

[13]Bijttebier P, Beck I, Claes L, Vandereycken W. Gray's Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory as a framework for research on personality–psychopathology associations. Clinical psychology review. 2009; 29(5):421-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.002

[14]Berger U, Anaki D. The behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) mediates major aspects of the relationship between disgust and OCD symptomology. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2014; 3(3):249-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.06.004

[15]Olatunji BO, Haidt J, McKay D, David B. Core, animal reminder, and contamination disgust: Three kinds of disgust with distinct personality, behavioral, physiological, and clinical correlates. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008; 42(5):1243–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.009

[16]Oaten M, Stevenson RJ, Case TI. Disgust as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Psychological Bulletin. 2009; 135(2):303–21. doi: 10.1037/a0014823

[17]Cisler JM, Olatunji BO, Sawchuk CN, Lohr JM. Specificity of emotional maintenance processes among contamination fears and blood–injection–injury fears. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008; 22(5):915–23. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.006

[18]Berle D, Starcevic V, Brakoulias V, Sammut P, Milicevic D, Hannan A, et al. Disgust propensity in obsessive–compulsive disorder: Cross-sectional and prospective relationships. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2012; 43(1):656–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.002

[19]Olatunji BO, Ebesutani C, David B, Fan Q, McGrath PB. Disgust proneness and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in a clinical sample: Structural differentiation from negative affect. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011; 25(7):932–8. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.006

[20]Coles ME, Schofield CA, Pietrefesa AS. Behavioral inhibition and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006; 20(8):1118–32. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.003

[21]Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2010.

[22]Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994; 67(2):319–33. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319

[23]Poythress NG, Skeem JL, Weir J, Lilienfeld SO, Douglas KS, Edens JF, et al. Psychometric properties of Carver and White’s (1994) BIS/BAS scales in a large sample of offenders. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008; 45(8):732–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.021

[24]Mohammadi N. [The psychometric properties of the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and Behavioral Activation System (BAS) scales among students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology & Personality. 2008; 1(28):61-68

[25]Haidt J, McCauley C, Rozin P. Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994; 16(5):701–13. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7

[26]Karsazi H, Nasiri M, Hashemi-nosratabad T. [Factor analysis and evaluation of internal structure of disgust sensitivity scale (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017; 8(4):49-60.

[27]Mohammadi A, Zamani R, Ladan F. [Validation of the Persian version of the obsessive-compulsive inventory-revised in a student sample (Persian)]. Psychological Research. 2008; 11(1-2):66-78.

[28]Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8.80 for Windows [Computer software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2006.

[29]Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988; 103(3):411–23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

[30]Chou CP, Bentler PM. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, California; 1995.

[31]Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999; 6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

[32]Bentler PM. EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, California: Multivariate Software; 1995.

[33]Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008; 40(3):879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879

[34]Fullana MA, Mataix-Cols D, Caseras X, Alonso P, Manuel Menchón J, Vallejo J, et al. High sensitivity to punishment and low impulsivity in obsessive-compulsive patients with hoarding symptoms. Psychiatry Research. 2004; 129(1):21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.02.017

[35]Kort S. Autistic traits in hoarding disorder: a comparative study between patients with hoarding disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder [MSc. thesis]. Utrecht: Utrecht University; 2012.

[36]Corr PJ. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity theory: Tests of the joint subsystems hypothesis of anxiety and impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002; 33(4):511–32. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(01)00170-2

[37]Sellbom M, Ben-Porath YS, Bagby RM. On the hierarchical structure of mood and anxiety disorders: Confirmatory evidence and elaboration of a model of temperament markers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008; 117(3):576–90. doi: 10.1037/a0012536

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2016/11/5 | Accepted: 2017/05/8 | Published: 2018/01/1

Received: 2016/11/5 | Accepted: 2017/05/8 | Published: 2018/01/1

References

1. Mataix-Cols D, Do Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF. A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005; 162(2):228-38. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.228 [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.228]

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry [N. Poorafkari Persian trans]. Tehran: Shahr Ab; 2009.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system (Oxford psychology series). New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

5. Matthews G, Gilliland K. The personality theories of HJ. Eysenck and JA. Gray: A comparative review. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999; 26(4):583–626. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00158-5 [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00158-5]

6. Gray JA. Framework for taxonomy of psychiatric disorders. In: van Goozen SHM, Van de Poll NE, Sergeant JA, Van Goozen SHM, editors. Emotions: Es-says on Emotion Theory. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 1994.

7. Meyer B, Johnson SL, Winters R. Responsiveness to threat and incentive in bipolar disorder: Relations of the BIS/BAS scales with symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001; 23(3):133-43. doi: 10.1023/a:1010929402770 [DOI:10.1023/A:1010929402770]

8. Gray JA. Neural systems, emotion and personality. In: Madden J, editor. Neurobiology of Learning, Emotion and Affect. New York: Raven Press; 1991.

9. Muris P, Meesters C, Spinder M. Relationships between child-and parent-reported behavioural inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression in nor-mal adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003; 34(5):759-71. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00069-7 [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00069-7]

10. Saxena S, Rauch SL. Functional neuroimaging and the neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000; 23(3):563-86. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70181-7 [DOI:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70181-7]

11. Baxter LR, Schwartz JM, Bergman KS, Szuba MP, Guze BH, Mazziotta JC, et al. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992; 49(9):681-9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090009002 [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090009002]

12. Gray JA. Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cognition & Emotion. 1990; 4(3):269-88. doi: 10.1080/02699939008410799 [DOI:10.1080/02699939008410799]

13. Bijttebier P, Beck I, Claes L, Vandereycken W. Gray's Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory as a framework for research on personality–psychopathology associa-tions. Clinical psychology review. 2009; 29(5):421-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.002 [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.002]

14. Berger U, Anaki D. The behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) mediates major aspects of the relationship between disgust and OCD symptomology. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2014; 3(3):249-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.06.004 [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.06.004]

15. Olatunji BO, Haidt J, McKay D, David B. Core, animal reminder, and contamination disgust: Three kinds of disgust with distinct personality, behavior-al, physiological, and clinical correlates. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008; 42(5):1243–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.009 [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.009]

16. Oaten M, Stevenson RJ, Case TI. Disgust as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Psychological Bulletin. 2009; 135(2):303–21. doi: 10.1037/a0014823 [DOI:10.1037/a0014823]

17. Cisler JM, Olatunji BO, Sawchuk CN, Lohr JM. Specificity of emotional maintenance processes among contamination fears and blood–injection–injury fears. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008; 22(5):915–23. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.006 [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.006]

18. Berle D, Starcevic V, Brakoulias V, Sammut P, Milicevic D, Hannan A, et al. Disgust propensity in obsessive–compulsive disorder: Cross-sectional and prospective relationships. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2012; 43(1):656–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.002 [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.002]

19. Olatunji BO, Ebesutani C, David B, Fan Q, McGrath PB. Disgust proneness and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in a clinical sample: Structural differen-tiation from negative affect. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011; 25(7):932–8. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.006 [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.006]

20. Coles ME, Schofield CA, Pietrefesa AS. Behavioral inhibition and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006; 20(8):1118–32. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.003 [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.003]

21. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2010.

22. Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994; 67(2):319–33. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319 [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319]

23. Poythress NG, Skeem JL, Weir J, Lilienfeld SO, Douglas KS, Edens JF, et al. Psychometric properties of Carver and White's (1994) BIS/BAS scales in a large sample of offenders. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008; 45(8):732–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.021 [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.021]

24. Mohammadi N. [The psychometric properties of the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and Behavioral Activation System (BAS) scales among students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology & Personality. 2008; 1(28):61-68

25. Haidt J, McCauley C, Rozin P. Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Personality and Indi-vidual Differences. 1994; 16(5):701–13. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7 [DOI:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7]

26. Karsazi H, Nasiri M, Hashemi-nosratabad T. [Factor analysis and evaluation of internal structure of disgust sensitivity scale (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017; 8(4):49-60.

27. Mohammadi A, Zamani R, Ladan F. [Validation of the Persian version of the obsessive-compulsive inventory-revised in a student sample (Persian)]. Psy-chological Research. 2008; 11(1-2):66-78.

28. Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8.80 for Windows [Computer software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2006.

29. Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988; 103(3):411–23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411]

30. Chou CP, Bentler PM. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, California; 1995.

31. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Model-ing: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999; 6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI:10.1080/10705519909540118]

32. Bentler PM. EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, California: Multivariate Software; 1995.

33. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008; 40(3):879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879 [DOI:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879]

34. Fullana MA, Mataix-Cols D, Caseras X, Alonso P, Manuel Menchón J, Vallejo J, et al. High sensitivity to punishment and low impulsivity in obsessive-compulsive patients with hoarding symptoms. Psychiatry Research. 2004; 129(1):21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.02.017 [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2004.02.017]

35. Kort S. Autistic traits in hoarding disorder: a comparative study between patients with hoarding disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder [MSc. thesis]. Utrecht: Utrecht University; 2012.

36. Corr PJ. Gray's reinforcement sensitivity theory: Tests of the joint subsystems hypothesis of anxiety and impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002; 33(4):511–32. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(01)00170-2 [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00170-2]

37. Sellbom M, Ben-Porath YS, Bagby RM. On the hierarchical structure of mood and anxiety disorders: Confirmatory evidence and elaboration of a model of temperament markers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008; 117(3):576–90. doi: 10.1037/a0012536 [DOI:10.1037/a0012536]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |