Tue, Dec 2, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 31, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

IJPCP 2025, 31(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Pirzade M, Fazelirad H, Peyvastegar M. Mediating Role of Anxiety Sensitivity and Repetitive Negative Thinking in the Relationship of Self-compassion and Cognitive Fusion With Cyberchondria. IJPCP 2025; 31 (1)

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4394-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4394-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran. , Mimpirzade01@gmail.com

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Science, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Science, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Cyberchondria, Cognitive fusion, Self-Compassion Anxiety sensitivity, Repetitive negative thinking

Full-Text [PDF 1969 kb]

(410 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (538 Views)

Full-Text: (492 Views)

Introduction

Today, the Internet is used for many purposes, such as searching for health information. Cyberchondria refers to an excessive pattern of using the Internet for health research that often leads to increased levels of anxiety or distress. One contributing factor that has been positively linked to both anxiety and problematic smartphone use and plays a significant role in maintaining obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is the concept of cognitive fusion. However, it has not yet been studied in the field of cyberchondria. Cognitive fusion is defined as the tendency for both overt and covert behaviors to be overly influenced by cognition. According to Hayes, having a thought can sometimes lead to discomfort and suffering even when no painful external stimulus is present. This implies that individuals with higher levels of cognitive fusion may be at greater risk of experiencing distress across various health aspects. Another concept that is linked to anxiety and depression, OCD symptoms, and Internet addiction, but has not been explored in the field of cyberchondria, is self-compassion. Self-compassion involves treating oneself with kindness and support in tough times.

It is important to understand how psychological mechanisms, such as self-compassion and cognitive fusion, interact with cyberchondria. One important factor that can influence the explanation of this relationship is the concept of anxiety sensitivity (AS), which is defined as the fear of emotions and physical symptoms related to anxiety. This fear stems from an individual’s belief that such anxiety-related experiences can lead to harmful physical, psychological, or social consequences. Research has shown a distinct positive association between AS and cyberchondria, indicating that AS may play a significant role in the development of cyberchondria. Repetitive negative thinking (RNT) is another significant factor that has been shown to be related to self-compassion, anxiety, depression, cognitive fusion, and OCD symptoms. It has been conceptualized as a transdiagnostic risk factor that contributes to the onset and maintenance of various depressive and anxiety disorders.

The relationship between cyberchondria and key concepts such as cognitive fusion and self-compassion has not been thoroughly explored. Additionally, the mediating role of AS in this relationship remains unclear. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine whether AS and RNT mediate the relationship of self-compassion and cognitive fusion with cyberchondria.

Methods

This is a descriptive-correlational study, utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM). The study population includes all university students in Tehran and Mazandaran provinces in 2024. Using Soper’s statistics calculator, and considering an effect size of 0.3, a test power of 0.8, and an alpha value of 0.5, the minimum sample size was calculated to be 137. The inclusion criteria were age 18-45 years, studying in one of the university courses, and consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were a lack of cooperation or return of incomplete questionnaires. The data collection tools included:

Cyberchondria severity scale-12 (CSS-12)

Developed by McElroy in 2019, CSS-12 has 12 items measuring four dimensions: Excessiveness, compulsion, distress, and reassurance seeking. Responses are rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s α for the overall scale is 0.94; for the subscales, it ranges from 0.75 (distress) to 0.95 (compulsion). In a study conducted in Iran by Foroughi et al. [68] the reported Cronbach’s α for the overall scale and the dimensions of excessiveness, distress, reassurance seeking, and compulsion were 0.91, 0.81, 0.73, 0.77, and 0.82, respectively. In our current study, the overall Cronbach’s α value was obtained as 0.85. For the subscales, it ranged from 0.73 to 0.84.

Cognitive fusion questionnaire (CFQ)

Developed by Gillanders et al. [26] it has a one-factor structure with seven items. The Cronbach’s α of CFQ for various samples ranges from 0.88 to 0.93, and its test-retest reliability is 0.80. For its Persian version, Soltani et al. [58] demonstrated a single-factor model that explained 89.54% of the total variance. In our study, the Cronbach’s α was obtained as 0.91, confirming the instrument’s internal consistency.

Self-compassion scale (CSC)

It is a 12-item tool developed by Neff in 2003 that measures six components of self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification, rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Therefore, the total score is between 12 and 60, with higher scores indicating greater self-compassion. Neff reported an overall Cronbach’s α value of 0.92 for CSC. Each subscale also demonstrated good internal consistency, with alpha values ranging from 0.75 to 0.81. Additionally, the test-retest reliability at a two-week interval was reported as 0.93. For its Persian version, Shahbazi et al. [70] found that both concurrent validity and convergent validity of the CSC were satisfactory, and the overall Cronbach’s α value was 0.91, and for the subscales of self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification were 0.83, 0.87, 0.91, 0.88, 0.92, and 0.77, respectively. In our study, we obtained an alpha value of 0.84 for the overall scale and 0.52-0.63 for the subscales.

AS inventory (ASI)

Developed by Floyd et al. [71] it is a self-report tool with 16 items, rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (very little) to 5 (very much). The Cronbach’s α value for ASI is between 0.80 and 0.90. Foroughi et al. [72] reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.90 for the Persian version. In our study, the Cronbach’s α value for the entire scale was 0.87.

Repetitive thinking questionnaire-10 (RTQ-10)

Developed in 2010 by McEvoy et al. [60] it is a 10-item tool to assess RNT, rated on a 5-point scale from one (not true at all) to five (very true). This instrument has high internal consistency (α=0.81) and a strong correlation with the 27-item RTQ score. Its test-retest reliability at a two-week interval ranges from 0.72 to 0.93. In Iran, Akbari reported a test-retest reliability of 0.76 at a two-week interval and a Cronbach’s α of over 0.91. In our study, the Cronbach’s α value for the entire scale was 0.90.

Before analyzing the data, we examined the assumptions of normality for the research variables by assessing the skewness and kurtosis values. The data were analyzed using SEM and path analysis in Amos software, version 29.

Results

Finally, 630 students participated in this study. The skewness and kurtosis values indicated the normality of data distribution. The structural model’s fit indices also fell within the desired range: χ2=384.36; χ2/df = 3.026, CFI=0.95, RMSEA=0.05, GFI=0.93, IFI=0.95, and SRMR=0.04. The two subscales, self-kindness and over-identification, were excluded from the research model due to Cronbach’s alpha values below the acceptable threshold.

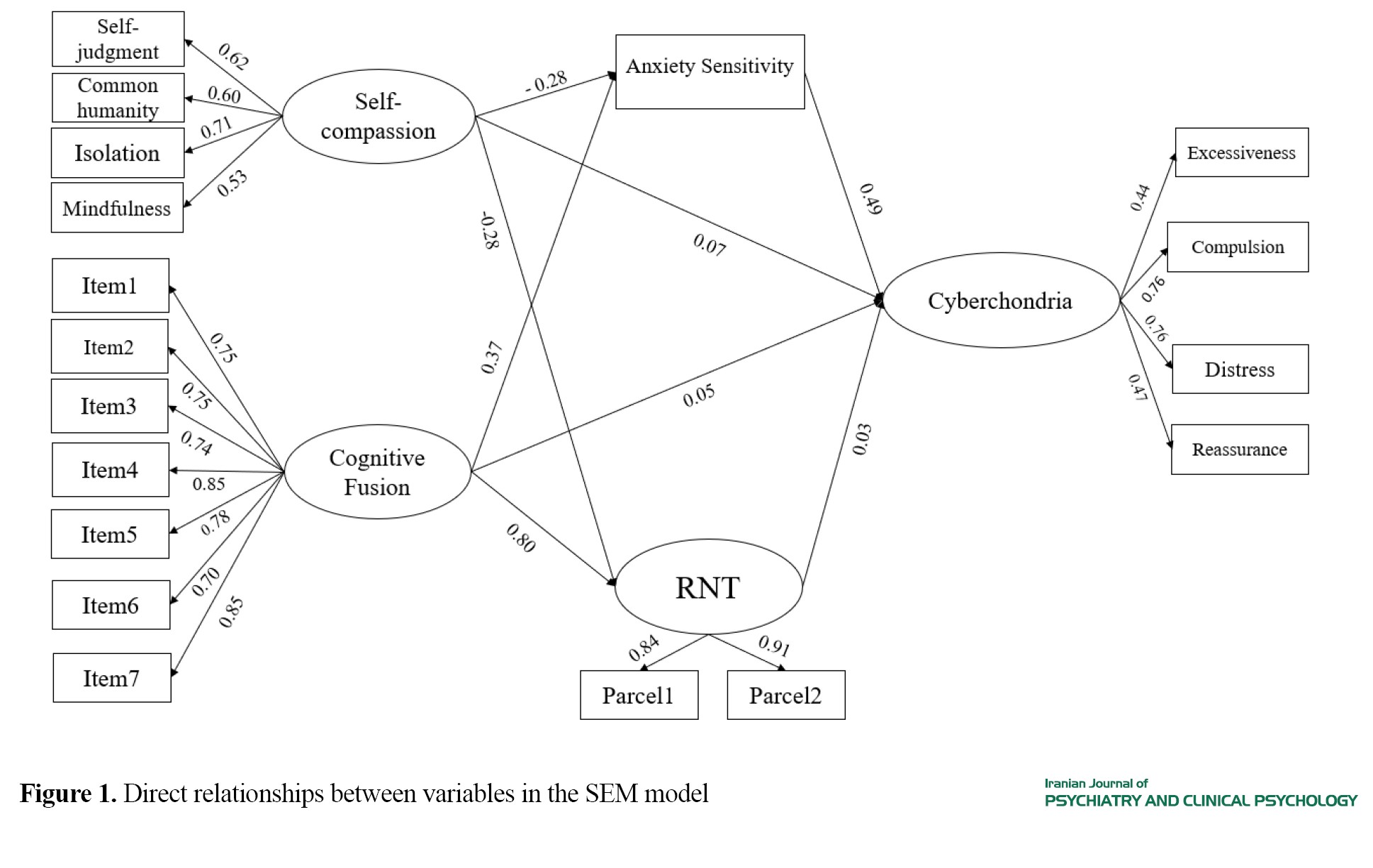

The direct path from self-compassion to cyberchondria (t=1.253, β=0.079), from cognitive fusion to cyberchondria (t=0.540, β=0.054), and from RNT to cyberchondria (t=0.322, β=0.034) was not significant. However, the direct path from AS to cyberchondria was significant (t= 7.658, β=0.496). The direct path from self-compassion to AS (t=-6.130, β=-0.286) and from cognitive fusion to AS (t=9.811, β=0.375) was significant. Furthermore, the direct path from self-compassion to RNT (t=-7.324, β=-0.281) and from cognitive fusion to RNT (t=22.503, β=0.801) was significant. Figure 1 illustrates the direct relationships between variables in the SEM model.

Today, the Internet is used for many purposes, such as searching for health information. Cyberchondria refers to an excessive pattern of using the Internet for health research that often leads to increased levels of anxiety or distress. One contributing factor that has been positively linked to both anxiety and problematic smartphone use and plays a significant role in maintaining obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is the concept of cognitive fusion. However, it has not yet been studied in the field of cyberchondria. Cognitive fusion is defined as the tendency for both overt and covert behaviors to be overly influenced by cognition. According to Hayes, having a thought can sometimes lead to discomfort and suffering even when no painful external stimulus is present. This implies that individuals with higher levels of cognitive fusion may be at greater risk of experiencing distress across various health aspects. Another concept that is linked to anxiety and depression, OCD symptoms, and Internet addiction, but has not been explored in the field of cyberchondria, is self-compassion. Self-compassion involves treating oneself with kindness and support in tough times.

It is important to understand how psychological mechanisms, such as self-compassion and cognitive fusion, interact with cyberchondria. One important factor that can influence the explanation of this relationship is the concept of anxiety sensitivity (AS), which is defined as the fear of emotions and physical symptoms related to anxiety. This fear stems from an individual’s belief that such anxiety-related experiences can lead to harmful physical, psychological, or social consequences. Research has shown a distinct positive association between AS and cyberchondria, indicating that AS may play a significant role in the development of cyberchondria. Repetitive negative thinking (RNT) is another significant factor that has been shown to be related to self-compassion, anxiety, depression, cognitive fusion, and OCD symptoms. It has been conceptualized as a transdiagnostic risk factor that contributes to the onset and maintenance of various depressive and anxiety disorders.

The relationship between cyberchondria and key concepts such as cognitive fusion and self-compassion has not been thoroughly explored. Additionally, the mediating role of AS in this relationship remains unclear. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine whether AS and RNT mediate the relationship of self-compassion and cognitive fusion with cyberchondria.

Methods

This is a descriptive-correlational study, utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM). The study population includes all university students in Tehran and Mazandaran provinces in 2024. Using Soper’s statistics calculator, and considering an effect size of 0.3, a test power of 0.8, and an alpha value of 0.5, the minimum sample size was calculated to be 137. The inclusion criteria were age 18-45 years, studying in one of the university courses, and consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were a lack of cooperation or return of incomplete questionnaires. The data collection tools included:

Cyberchondria severity scale-12 (CSS-12)

Developed by McElroy in 2019, CSS-12 has 12 items measuring four dimensions: Excessiveness, compulsion, distress, and reassurance seeking. Responses are rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s α for the overall scale is 0.94; for the subscales, it ranges from 0.75 (distress) to 0.95 (compulsion). In a study conducted in Iran by Foroughi et al. [68] the reported Cronbach’s α for the overall scale and the dimensions of excessiveness, distress, reassurance seeking, and compulsion were 0.91, 0.81, 0.73, 0.77, and 0.82, respectively. In our current study, the overall Cronbach’s α value was obtained as 0.85. For the subscales, it ranged from 0.73 to 0.84.

Cognitive fusion questionnaire (CFQ)

Developed by Gillanders et al. [26] it has a one-factor structure with seven items. The Cronbach’s α of CFQ for various samples ranges from 0.88 to 0.93, and its test-retest reliability is 0.80. For its Persian version, Soltani et al. [58] demonstrated a single-factor model that explained 89.54% of the total variance. In our study, the Cronbach’s α was obtained as 0.91, confirming the instrument’s internal consistency.

Self-compassion scale (CSC)

It is a 12-item tool developed by Neff in 2003 that measures six components of self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification, rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Therefore, the total score is between 12 and 60, with higher scores indicating greater self-compassion. Neff reported an overall Cronbach’s α value of 0.92 for CSC. Each subscale also demonstrated good internal consistency, with alpha values ranging from 0.75 to 0.81. Additionally, the test-retest reliability at a two-week interval was reported as 0.93. For its Persian version, Shahbazi et al. [70] found that both concurrent validity and convergent validity of the CSC were satisfactory, and the overall Cronbach’s α value was 0.91, and for the subscales of self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification were 0.83, 0.87, 0.91, 0.88, 0.92, and 0.77, respectively. In our study, we obtained an alpha value of 0.84 for the overall scale and 0.52-0.63 for the subscales.

AS inventory (ASI)

Developed by Floyd et al. [71] it is a self-report tool with 16 items, rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (very little) to 5 (very much). The Cronbach’s α value for ASI is between 0.80 and 0.90. Foroughi et al. [72] reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.90 for the Persian version. In our study, the Cronbach’s α value for the entire scale was 0.87.

Repetitive thinking questionnaire-10 (RTQ-10)

Developed in 2010 by McEvoy et al. [60] it is a 10-item tool to assess RNT, rated on a 5-point scale from one (not true at all) to five (very true). This instrument has high internal consistency (α=0.81) and a strong correlation with the 27-item RTQ score. Its test-retest reliability at a two-week interval ranges from 0.72 to 0.93. In Iran, Akbari reported a test-retest reliability of 0.76 at a two-week interval and a Cronbach’s α of over 0.91. In our study, the Cronbach’s α value for the entire scale was 0.90.

Before analyzing the data, we examined the assumptions of normality for the research variables by assessing the skewness and kurtosis values. The data were analyzed using SEM and path analysis in Amos software, version 29.

Results

Finally, 630 students participated in this study. The skewness and kurtosis values indicated the normality of data distribution. The structural model’s fit indices also fell within the desired range: χ2=384.36; χ2/df = 3.026, CFI=0.95, RMSEA=0.05, GFI=0.93, IFI=0.95, and SRMR=0.04. The two subscales, self-kindness and over-identification, were excluded from the research model due to Cronbach’s alpha values below the acceptable threshold.

The direct path from self-compassion to cyberchondria (t=1.253, β=0.079), from cognitive fusion to cyberchondria (t=0.540, β=0.054), and from RNT to cyberchondria (t=0.322, β=0.034) was not significant. However, the direct path from AS to cyberchondria was significant (t= 7.658, β=0.496). The direct path from self-compassion to AS (t=-6.130, β=-0.286) and from cognitive fusion to AS (t=9.811, β=0.375) was significant. Furthermore, the direct path from self-compassion to RNT (t=-7.324, β=-0.281) and from cognitive fusion to RNT (t=22.503, β=0.801) was significant. Figure 1 illustrates the direct relationships between variables in the SEM model.

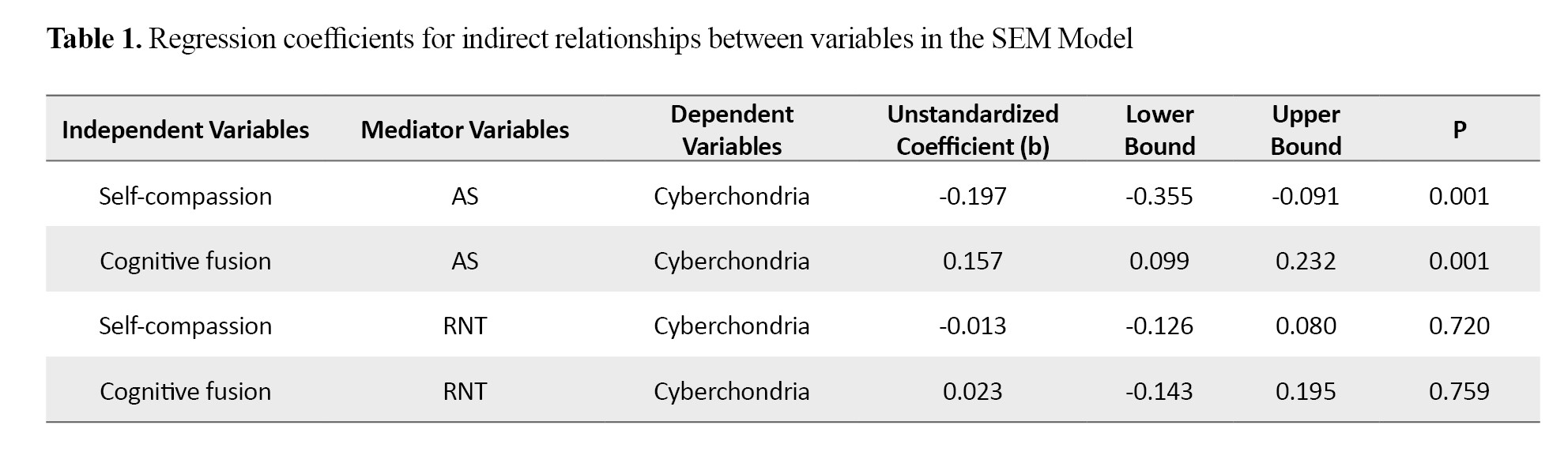

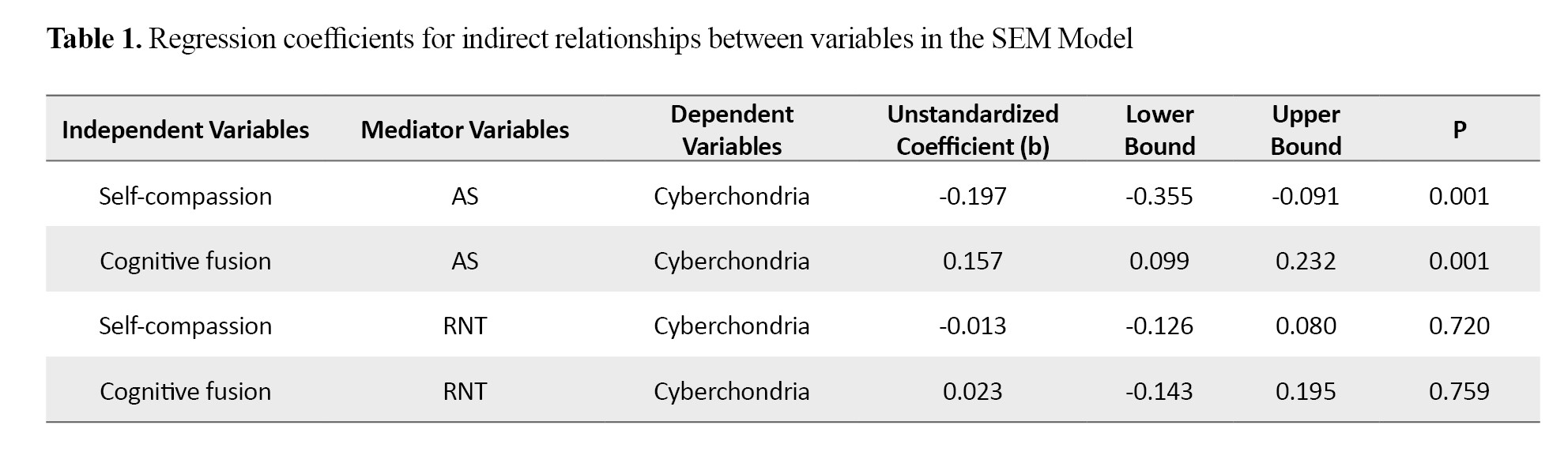

The bootstrap method was employed with 5,000 sampling processes to assess the indirect effects. The results indicated that self-compassion had a significant indirect effect on cyberchondria through AS (b=-0.197, P<0.05). Similarly, cognitive fusion showed a significant indirect effect on cyberchondria through AS (b=0.157, P<0.05). However, the indirect effect of self-compassion on cyberchondria through RNT (b=-0.013, P>0.05) and the indirect effect of cognitive fusion on cyberchondria through RNT (b=0.023, P>0.05) were not significant. Table 1 presents the coefficients for indirect relationships.

Conclusion

The relationship between self-compassion and cyberchondria was significantly mediated by AS. When a person has low self-compassion, they may experience self-blame in response to unfamiliar or unexpected bodily sensations. They might worry that they have contracted a serious illness due to their carelessness or inaction, which in turn can heighten their anxiety levels. Consequently, excessive and repetitive searching for health information online can become a maladaptive coping strategy for these individuals.

The relationship between cognitive fusion and cyberchondria was significantly mediated by AS. This finding suggests that cognitive fusion causes people to perceive their thoughts as if they are happening in the present moment. When a person’s behavior is heavily influenced by their thoughts—especially when they experience high cognitive fusion and have a strong sensitivity to anxiety—they may misinterpret bodily sensations and the implications of feeling anxious. As a result, they can become intensely anxious over even slight physical changes. This anxiety often leads them to engage in excessive and repetitive online health searches in an attempt to alleviate their concerns.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Alzahra University (Code: IR.ALZAHRA.REC.1403.046).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and investigation: Mehrane Pirzade; initial draft preparation: Mehrane Pirzade and Hadi Fazelirad; statistical analysis: Hadi Fazelirad; validation, editing & review: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

Conclusion

The relationship between self-compassion and cyberchondria was significantly mediated by AS. When a person has low self-compassion, they may experience self-blame in response to unfamiliar or unexpected bodily sensations. They might worry that they have contracted a serious illness due to their carelessness or inaction, which in turn can heighten their anxiety levels. Consequently, excessive and repetitive searching for health information online can become a maladaptive coping strategy for these individuals.

The relationship between cognitive fusion and cyberchondria was significantly mediated by AS. This finding suggests that cognitive fusion causes people to perceive their thoughts as if they are happening in the present moment. When a person’s behavior is heavily influenced by their thoughts—especially when they experience high cognitive fusion and have a strong sensitivity to anxiety—they may misinterpret bodily sensations and the implications of feeling anxious. As a result, they can become intensely anxious over even slight physical changes. This anxiety often leads them to engage in excessive and repetitive online health searches in an attempt to alleviate their concerns.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Alzahra University (Code: IR.ALZAHRA.REC.1403.046).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and investigation: Mehrane Pirzade; initial draft preparation: Mehrane Pirzade and Hadi Fazelirad; statistical analysis: Hadi Fazelirad; validation, editing & review: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Mestre-Bach G, Potenza MN. Cyberchondria: A growing concern during the covid-19 pandemic and a possible addictive disorder? Current Addiction Reports. 2023; 10(1):77-96. [DOI:10.1007/s40429-022-00462-3] [PMID]

- Andersson G, Titov N. Advantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2014; 13(1):4-11. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20083] [PMID]

- White RW, Horvitz E. Cyberchondria: Studies of the escalation of medical concerns in web search. ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS). 2009; 27(4):1 37. [DOI:10.1145/1629096.162910]

- Starcevic V, Aboujaoude E. Cyberchondria, cyberbullying, cybersuicide, cybersex: “New” psychopathologies for the 21st century? World Psychiatry. 2015; 14(1):97-100. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20195] [PMID]

- Starcevic V, Berle D, Arnáez S. Recent insights into cyberchondria. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2020; 22(11):56. [DOI:10.1007/s11920-020-01179-8] [PMID]

- Zheng H, Tandoc EC. Calling Dr. Internet: Analyzing news coverage of cyberchondria. Journalism Practice. 2022; 16(5):1001-17. [DOI:10.1080/17512786.2020.1824586]

- Starcevic V. Cyberchondria: Challenges of problematic online searches for health-related information. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2017; 86(3):129-33. [DOI:10.1159/000465525] [PMID]

- McElroy E, Shevlin M. The development and initial validation of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014; 28(2):259-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.007] [PMID]

- Starcevic V, Berle D. Cyberchondria: Towards a better understanding of excessive health-related Internet use. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2013; 13(2):205-13. [DOI:110.1586/ern.12.162] [PMID]

- Brown RJ, Skelly N, Chew-Graham CA. Online health research and health anxiety: A systematic review and conceptual integration. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2020; 27(2):e12299. [DOI:10.1111/cpsp.12299]

- Kefeli Col B, Gumusler Basaran A, Genc Kose B. The relationship between e-health literacy, health anxiety, cyberchondria, and death anxiety in university students that study in health related department. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2025; 18:1581-95. [DOI:10.2147/JMDH.S513017] [PMID]

- Yalçın İ, Boysan M, Eşkisu M, Çam Z. Health anxiety model of cyberchondria, fears, obsessions, sleep quality, and negative affect during COVID-19. Current Psychology 2022 ; 1-18. [PMID]

- Bajcar B, Babiak J, Olchowska-Kotala A. Cyberchondria and its measurement. The Polish adaptation and psychometric properties of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale CSS-PL. Psychiatria Polska. 2019; 53(1):49-60. [DOI:10.12740/PP/81799] [PMID]

- Ali SS, Hendawi NE, El-Ashry AM, Mohammed MS. The relationship between cyberchondria and health literacy among first-year nursing students: the mediating effect of health anxiety. BMC Nursing. 2024; 23(1):776. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-02396-9] [PMID]

- Vujić A, Volarov M, Latas M, Demetrovics Z, Kiraly O, Szabo A. Are cyberchondria and intolerance of uncertainty related to smartphone addiction? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2023 ; 1-19. [PMID]

- Fergus TA, Spada MM. Cyberchondria: Examining relations with problematic Internet use and metacognitive beliefs. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2017; 24(6):1322-30. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2102] [PMID]

- Fergus TA. The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS): An examination of structure and relations with health anxiety in a community sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014; 28(6):504-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.05.006] [PMID]

- Zangoulechi Z, Yousefi Z, Keshavarz N. The role of anxiety sensitivity, intolerance of uncertainty, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the prediction of cyberchondria. Advances in Bioscience and Clinical Medicine (ABCmed). 2018; 6(4):1-6. [DOI:10.7575/aiac.abcmed.v.6n.4p.1]

- Fergus TA. Cyberchondria and intolerance of uncertainty: Examining when individuals experience health anxiety in response to Internet searches for medical information. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2013; 16(10):735-9. [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2012.0671] [PMID]

- Fergus TA. I really believe I suffer from a health problem: Examining an association between cognitive fusion and healthy anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2015; 71(9):920-34. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22194] [PMID]

- Norr AM, Albanese BJ, Oglesby ME, Allan NP, Schmidt NB. Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as potential risk factors for cyberchondria. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015; 174:64-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.023] [PMID]

- Lee J, Won S, Chang SM, Kim BS, Lee SJ. Exploring the role of cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance in predicting smartphone use among medical university students. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2023; 28:18-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2023.03.004]

- Akbari M, Mohamadkhani S, Zarghami F. [The mediating role of cognitive fusion in explaining the relationship between emotional dysregulation with anxiety and depression: A transdiagnostic factor (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2016; 22(1):17-29. [Link]

- Xiong A, Lai X, Wu S, Yuan X, Tang J, Chen J, et al. Relationship between cognitive fusion, experiential avoidance, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; 12:655154. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655154] [PMID]

- Reuman L, Buchholz J, Abramowitz JS. Obsessive beliefs, experiential avoidance, and cognitive fusion as predictors of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptom dimensions. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2018; 9:15-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.06.001]

- Gillanders DT, Bolderston H, Bond FW, Dempster M, Flaxman PE, Campbell L, et al. The development and initial validation of the cognitive fusion questionnaire. Behavior Therapy. 2014; 45(1):83-101. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.001] [PMID]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Link]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Bunting K, Twohig M, Wilson KG. What is acceptance and commitment therapy? In: Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, editors. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. Boston: Springer; 2004. [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-23369-7_1]

- Solé E, Tomé-Pires C, de la Vega R, Racine M, Castarlenas E, Jensen MP, et al. Cognitive fusion and pain experience in young people. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2016; 32(7):602-8. [DOI:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000227] [PMID]

- Özkan S, Zale EL, Ring D, Vranceanu AM. Associations between pain catastrophizing and cognitive fusion in relation to pain and upper extremity function among hand and upper extremity surgery patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2017; 51(4):547-54. [DOI:10.1007/s12160-017-9877-1] [PMID]

- Bodenlos JS, Hawes ES, Burstein SM, Arroyo KM. Association of cognitive fusion with domains of health. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020; 18:9-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.001]

- Hughes M, Brown SL, Campbell S, Dandy S, Cherry MG. Self-compassion and anxiety and depression in chronic physical illness populations: A systematic review. Mindfulness. 2021; 12(7):1597-610. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-021-01602-y]

- Eichholz A, Schwartz C, Meule A, Heese J, Neumüller J, Voderholzer U. Self-compassion and emotion regulation difficulties in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2020; 27(5):630-9. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2451] [PMID]

- Leeuwerik T, Cavanagh K, Strauss C. The association of trait mindfulness and self-compassion with obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms: Results from a large survey with treatment-seeking adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2020; 44:120-35. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-019-10049-4]

- Moniri R, Pahlevani Nezhad K, Lavasani FF. Investigating Anxiety and Fear of COVID-19 as Predictors of Internet Addiction With the Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Cognitive Emotion Regulation. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022; 13:841870. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.841870] [PMID]

- Neff K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003; 2(2):85-101. [DOI:10.1080%2F15298860309032]

- Neff KD, Knox MC, Long P, Gregory K. Caring for others without losing yourself: An adaptation of the Mindful Self-Compassion Program for Healthcare Communities. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2020; 76(9):1543-62. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.23007] [PMID]

- Neff KD. Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology. 2023; 74:193-218. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047] [PMID]

- Mousavipour SP, Bavi S. Effects of self-compassion therapy on perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity in women with multiple sclerosis. Women’s Health Bulletin. 2024; 11(3):180-7. [DOI:10.30476/whb.2024.102366.1287]

- Rahmani S, Rahmati A, Rezaei SA, Pishgahi B. [The effectiveness of self-compassion therapy on cognitive emotion regulation strategies and anxiety sensitivity in female nurses (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing ( IJPN ). 2020 ; 8(4):99-110. [Link]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986; 24(1):1-8. [DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9] [PMID]

- Reiss S. Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clinical Psychology Review. 1991; 11(2):141-53. [DOI:10.1016/0272-7358(91)90092-9]

- Stein MB, Jang KL, Livesley WJ. Heritability of Anxiety Sensitivity: A Twin Study. American Journal of Psychiatry; 1999; 156(2):246-51. [DOI:10.1176/ajp.156.2.246] [PMID]

- Stewart SH, Buffett-Jerrott SE, Kokaram R. Heartbeat awareness and heart rate reactivity in anxiety sensitivity: A further investigation.Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2001; 15(6):535-53. [DOI:10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00080-9] [PMID]

- Abu Khait A, Mrayyan MT, Al-Rjoub S, Rababa M, Al-Rawashdeh S. Cyberchondria, anxiety sensitivity, hypochondria, and internet addiction: Implications for mental health professionals. Curr Psychol 2022; 2022:1-12. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-022-03815-3] [PMID]

- Hashemi SGS, Hosseinnezhad S, Dini S, Griffiths MD, Lin C-Y, Pakpour AH. The mediating effect of the cyberchondria and anxiety sensitivity in the association between problematic internet use, metacognition beliefs, and fear of COVID-19 among Iranian online population. Heliyon. 2020; 6(10):e05135. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05135] [PMID]

- Anderberg JL, Baker D, Kalantar EA, Berghoff CR. Cognitive fusion accounts for the relation of anxiety sensitivity cognitive concerns and rumination. Current Psychology. 2023; 43:4475-81. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-023-04674-2]

- Anderberg L. Breaking the cognitive spell: Cognitive fusion mediates the relation of cognitive anxiety sensitivity and rumination in undergraduate college students [Honors Thesis]. Vermillion: University of South Dakota ; 2021. [Link]

- Bardeen JR, Fergus TA, Orcutt HK. The moderating role of experiential avoidance in the prospective relationship between anxiety sensitivity and anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2014; 38(4):465-71. [Link]

- Egan SJ, Rees CS, Delalande J, Greene D, Fitzallen G, Brown S, et al. A review of self-compassion as an active ingredient in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression in young people. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2022; 49(3):385-403. [DOI:10.1007/s10488-021-01170-2] [PMID]

- Wadsworth LP, Forgeard M, Hsu KJ, Kertz S, Treadway M, Björgvinsson T. Examining the role of repetitive negative thinking in relations between positive and negative aspects of self-compassion and symptom improvement during intensive treatment. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2018; 42(3):236-49. [Link]

- Casali N, Ghisi M, Jansen P, Feraco T, Meneghetti C. What can affect competition anxiety in athletes? The role of self-compassion and repetitive negative thinking. Psychological Reports. 2022; 125(4):2009-28. [DOI:10.1177/00332941211017258] [PMID]

- Cabaços C, Macedo A, Carneiro M, Brito MJ, Amaral AP, Araújo A, et al. The mediating role of self-compassion and repetitive negative thinking in the relationship between perfectionism and burnout in health-field students: A prospective study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2023; 213:112314. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2023.112314]

- Vargas-Nieto JC, Montorio I, Gantiva C, Froufe M. Dispositional mindfulness is associated with less cognitive fusion and better effortful control in young people: The mediating role of repetitive negative thinking. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología. 2022; 54:205-13. [Link]

- Oliveira J, Pedras S, Inman RA, Ramalho SM. Latent profiles of emotion regulation among university students: Links to repetitive negative thinking, internet addiction, and subjective wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology. 2024; 15:1272643. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1272643] [PMID]

- Brailovskaia J, Stirnberg J, Rozgonjuk D, Margraf J, Elhai JD. From low sense of control to problematic smartphone use severity during Covid-19 outbreak: The mediating role of fear of missing out and the moderating role of repetitive negative thinking. PLoS One. 2021; 16(12):e0261023. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0261023] [PMID]

- Zhao X, Shen L, Pei Y, Wu X, Zhou N. The relationship between sleep disturbance and obsessive- compulsive symptoms: The mediation of repetitive negative thinking and the moderation of experiential avoidance. Frontiers in Psychology. 2023; 14:1151399.[DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1151399] [PMID]

- Ehring T, Watkins ER. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008; 1(3):192-205. [DOI:10.1521/ijct.2008.1.3.192]

- Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin. 2008; 134(2):163-76. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163] [PMID]

- McEvoy PM, Watson H, Watkins ER, Nathan P. The relationship between worry, rumination, and comorbidity: Evidence for repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic construct. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013; 151(1):313-20. [PMID]

- Harvey AG, Watkins E, Mansell W, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford: : Oxford University Press; 2004. [DOI:10.1093/med:psych/9780198528883.001.0001]

- Statista. Number of smartphone users worldwide [Internet]. 2024 [Updated 30 July 2024]. Available from: [Link]

- Mrayyan MT, Abu Khait A, Al-Mrayat Y, Alkhawaldeh J, Alfayoumi I, Kutah OS, et al. Anxiety sensitivity moderates the relationship between internet addiction and cyberchondria among nurses. Journal of Health Psychology. 2024; 0(0). [DOI:10.1177/13591053241249634] [PMID]

- Gillanders D, Sinclair AK, MacLean M, Remington B. The impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on cognitive fusion in chronic pain: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Pain. 2024; 25(2):235-47.

- Neff KD, Germer C. The role of self-compassion in third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapies: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2022; 92:102110.

- Soper DS. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software] [Internet]. 2025 [2 September 2025]. Available from: [Link]

- McElroy E, Kearney M, Touhey J, Evans J, Cooke Y, Shevlin M. The CSS-12: Development and validation of a short-form version of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2019; 22(5):330-5. [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2018.0624] [PMID]

- Foroughi A, Taheri AA, Khanjani S, Mohammadpour M, Amiri S, Parvizifard A, et al. Psychometric Properties of Iranian Version of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale (Short-Form of CSS). Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet. 2022; 26(2):131-45. [DOI:10.1080/15398285.2022.2045668]

- Soltani E, Momenzadeh S, Hoseini SZ, Bahrainian SA. [Psychometric properties of the cognitive fusion questionnaire (Persian)]. Pejouhandeh. 2016; 21(5):290-7. [Link]

- Shahbazi M, Rajabi G, MaghamiA, Jelodari A. [Confirmation structure of the Persian version of the revised grading scale of self-compassion in a group of prisoners (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Models and Methods. 2015; 6(19)31-46. [Link]

- Floyd M, Garfield A, LaSota MT. Anxiety sensitivity and worry. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005; 38(5):1223-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2004.08.005]

- Foroughi AA, Mohammadpour M, Khanjani S, Pouyanfard S, Dorouie N, Parvizi Fard AA. Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3). Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2019; 41(3):254-61. [PMID]

- McEvoy PM, Mahoney AEJ, Moulds ML. Are worry, rumination, and post-event processing one and the same? Development of the Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010; 24(5):509-19. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.008] [PMID]

- Akbari M. [Validation and reliability of the 10-item Obsessive Thoughts Questionnaire in a non-clinical sample: A transdiagnostic tool (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017; 9(2):59-72. [DOI: 10.22075/jcp.2017.10345.]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999, 6(1):1-55. [DOI:10.1080/10705519909540118]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Link]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010; 37(2):197-206. [DOI:10.1086/651257]

- Hayes A. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the New Millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009; 76(4)):408-20. [DOI:10.1080/03637750903310360]

- Ingram RE, Luxton DD. Vulnerability-stress models. In: Hankin BL, Abela JRZ, editors. Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Link]

- Inwood E, Ferrari M. Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being. 2018; 10(2):215-35. [DOI:10.1111/aphw.12127] [PMID]

- Kirschner H, Kuyken W, Wright K, Roberts H, Brejcha C, Karl A. Soothing Your heart and feeling connected: A new experimental paradigm to study the benefits of self-compassion. Clinical Psychological Science. 2019; 7(3):545-65. [DOI:10.1177/2167702618812438] [PMID]

- Gilbert P. A brief outline of the evolutionary approach for compassion focused therapy. EC Psychology and Psychiatry. 2017; 218-27. [Link]

- Wheaton MG, Berman NC, Franklin JC, Abramowitz JS. Health Anxiety: Latent structure and associations with anxiety-related psychological processes in a student sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010; 32:565-74. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-010-9179-4]

- Elhai JD, Yang H, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. COVID-19 anxiety symptoms associated with problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese adults. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020; 274:576-82. [DOI:10.1016%2Fj.jad.2020.05.080] [PMID]

- Monteregge S, Tsagkalidou A, Cuijpers P, Spinhoven P. The effects of different types of treatment for anxiety on repetitive negative thinking: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2020; 27(2):e12316. [DOI:10.1037/h0101777]

- Kocakaya S, Kocakaya F. A structural equation modeling on factors of how experienced teachers affect the students’ science and mathematics achievements. Education Research International. 2014; 2014(1):490371. [Link]

- Gilbert P. An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behavior therapy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010; 3(2):97-112. [DOI:10.1521%2Fijct.2010.3.2.97]

- Germer C, Neff K. Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC). In: Itvzan I, editor. Handbook of mindfulness-based programs: Mindfulness Interventions from Education to Health and Therapy. London: Routledge; 2019. [DOI:10.4324%2F9781315265438-28]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2024/12/24 | Accepted: 2025/07/9 | Published: 2025/08/1

Received: 2024/12/24 | Accepted: 2025/07/9 | Published: 2025/08/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |