Tue, Jan 27, 2026

| فارسی

Volume 31, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

IJPCP 2025, 31(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nazari F, Bakhtiyari M, Golestani Fard M, Kianimoghadam A S, Mohajerin Iravani B, Farahani H. Investigating the Efficacy of a Dialectical Behavioral Therapy-Based Parenting Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. IJPCP 2025; 31 (1)

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4318-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4318-en.html

Fatemeh Nazari1

, Maryam Bakhtiyari2

, Maryam Bakhtiyari2

, Mahdiyeh Golestani Fard3

, Mahdiyeh Golestani Fard3

, Amir Sam Kianimoghadam1

, Amir Sam Kianimoghadam1

, Banafsheh Mohajerin Iravani1

, Banafsheh Mohajerin Iravani1

, Hojjatollah Farahani4

, Hojjatollah Farahani4

, Maryam Bakhtiyari2

, Maryam Bakhtiyari2

, Mahdiyeh Golestani Fard3

, Mahdiyeh Golestani Fard3

, Amir Sam Kianimoghadam1

, Amir Sam Kianimoghadam1

, Banafsheh Mohajerin Iravani1

, Banafsheh Mohajerin Iravani1

, Hojjatollah Farahani4

, Hojjatollah Farahani4

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Taleghani Hospital Research Development Unit, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Taleghani Hospital Research Development Unit, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran. ,maryam_bakhtiyari@sbmu.ac.ir

3- Department of Psychiatry, Clinical Research Development Unit of Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Taleghani Hospital Research Development Unit, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychiatry, Clinical Research Development Unit of Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 6981 kb]

(633 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1004 Views)

Full-Text: (712 Views)

Introduction

Self-harm refers to intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, regardless of suicidal motive or level of suicidal intent [1], which is often used as a coping mechanism to resolve a difficult situation and can have functions such as emotion regulation, pain level regulation, or self-punishment [2]. Self-harm is a broader concept that includes some degrees of intentionality and ranges from suicidal attempts to non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) [3]. Adolescent self-harm is a leading public health problem. The results of a study that was conducted on the high schools of the north of Iran show that the prevalence of self-harm was 54.9% (20.3% in females and 79.7% in males) [5]. Currently, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is the only format of psychotherapy that has been confirmed to decrease self-harm in adolescents [9]. However, in a study conducted in Norway, the mean number of self-harm behaviors during a 19-week treatment and the one-year follow-up period was 9 and 5.5, respectively, indicating that some participants continued to self-harm even when they were receiving treatment [7, 11]. Therefore, it seems that there is a need to increase the effectiveness of DBT for adolescents.

The results of the studies indicate that parenting styles play a major role in the formation and continuation of psychological problems of children and adolescents [12]. Since DBT is a treatment with strong evidence for improving emotion regulation, researchers have begun to examine how it can not only enhance psychopathology in adult patients but also improve parenting skills toward the goal of reducing psychopathology of adolescents [15]. In this regard, Berk et al. designed a parent-only DBT-based parenting intervention using the “walking the middle path skills” module from the DBT Skills Manual for Adolescents. This intervention is used as individual sessions for parents to provide the possibility of in-depth training of skills as well as implementation according to the special needs of each family [6].

Methods

The present study is a randomized clinical trial. The study inclusion criteria were as follows: Being 11-18 years old for adolescents and 30-50 years old for primary caregivers, the adolescent has attempted suicide or NSSI at least once in the past 3 months, having at least a high school diploma for the primary caregiver and not receiving any simultaneous treatment (psychological and pharmaceutical) by caregivers and adolescents. According to the inclusion criteria, 32 pairs (primary caregiver and adolescent) referred by a psychiatrist at Luqman Hospital through convenience sampling were randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups. Adolescents did not receive any treatment as part of the study. The caregivers in the experimental group received an 8-session parenting intervention by a PhD student in clinical psychology under supervision.

The participants who were in the control group were placed on the waiting list and received DBT-based parenting intervention from another therapist after completing the study. Both parents were encouraged to attend the sessions. However, if both parents could not attend, one parent was allowed to participate. The data were collected from both caregivers and adolescents at the baseline and post-test phases using the difficulty in emotion regulation scale (DERS); parenting style and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ); depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21); five-facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ); conflict behavior questionnaire (CBQ); and caregiver strain questionnaire-short form 11 (CGSQ-SF11). Then the obtained data were analyzed at descriptive and inferential levels. In the descriptive section, indicators such as mean and standard deviation were reported. Also, the assumptions of the covariance test (homogeneity of variances) were examined to analyze the main relationships between groups. However, the relevant tests were all significant in the present study, so the quade nonparametric analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze the dependent variables. The significance level in all the above cases is 0.05, and all analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 27.

Results

The results related to the demographic characteristics of the participants showed that the average age in the experimental group was 15.31 in adolescents and 41.43 in primary caregivers. Also, the average age in the adolescent control group was 15.43 and 41.75 in the primary caregivers. About 50% of adolescents in both experimental and control groups had a history of NSSI. Also, 100% of adolescents in the control and experimental groups attempted suicide, but 23.5% of participants in the experimental group and 31.3% of the control group reported previous suicide attempts.

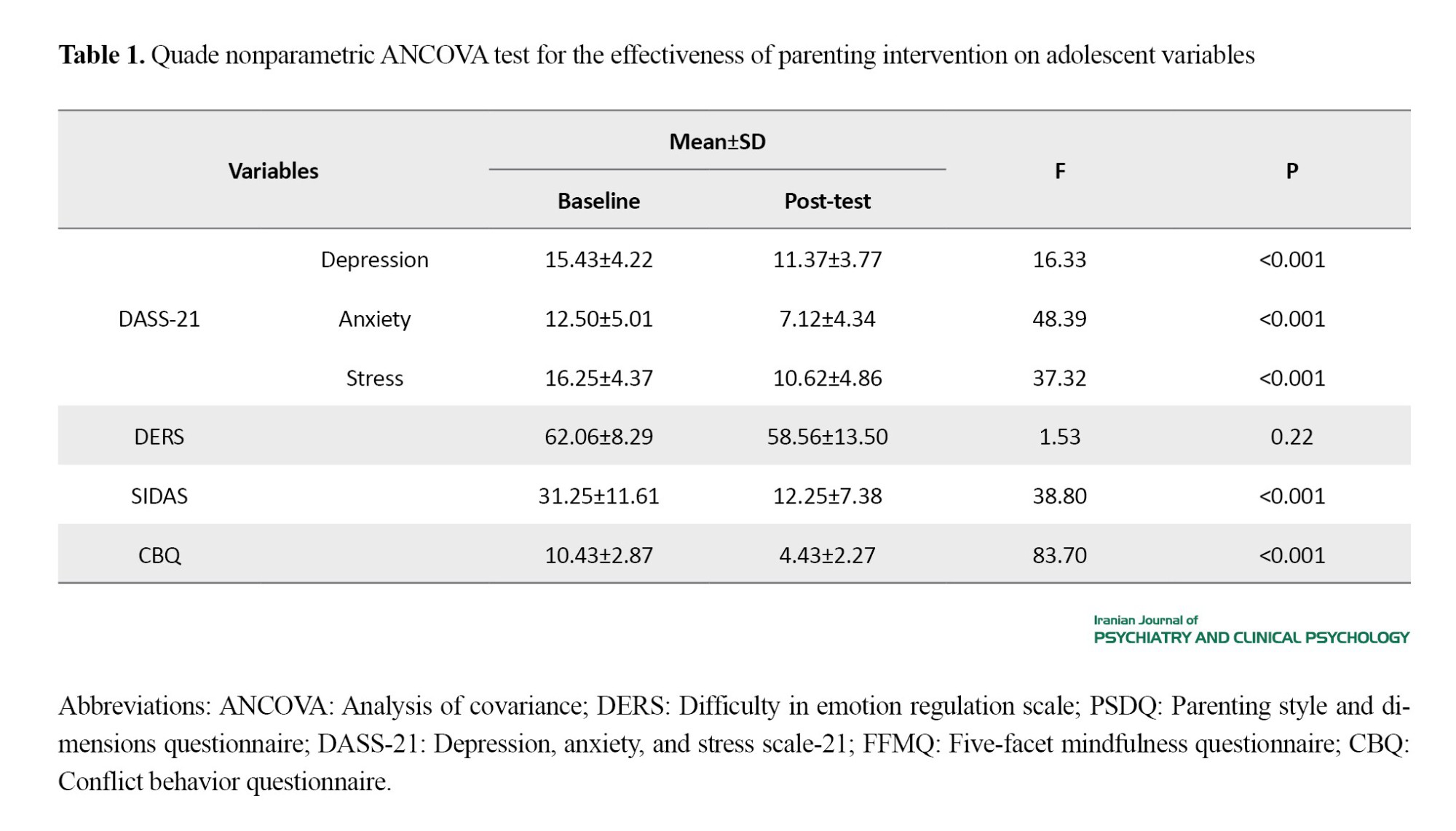

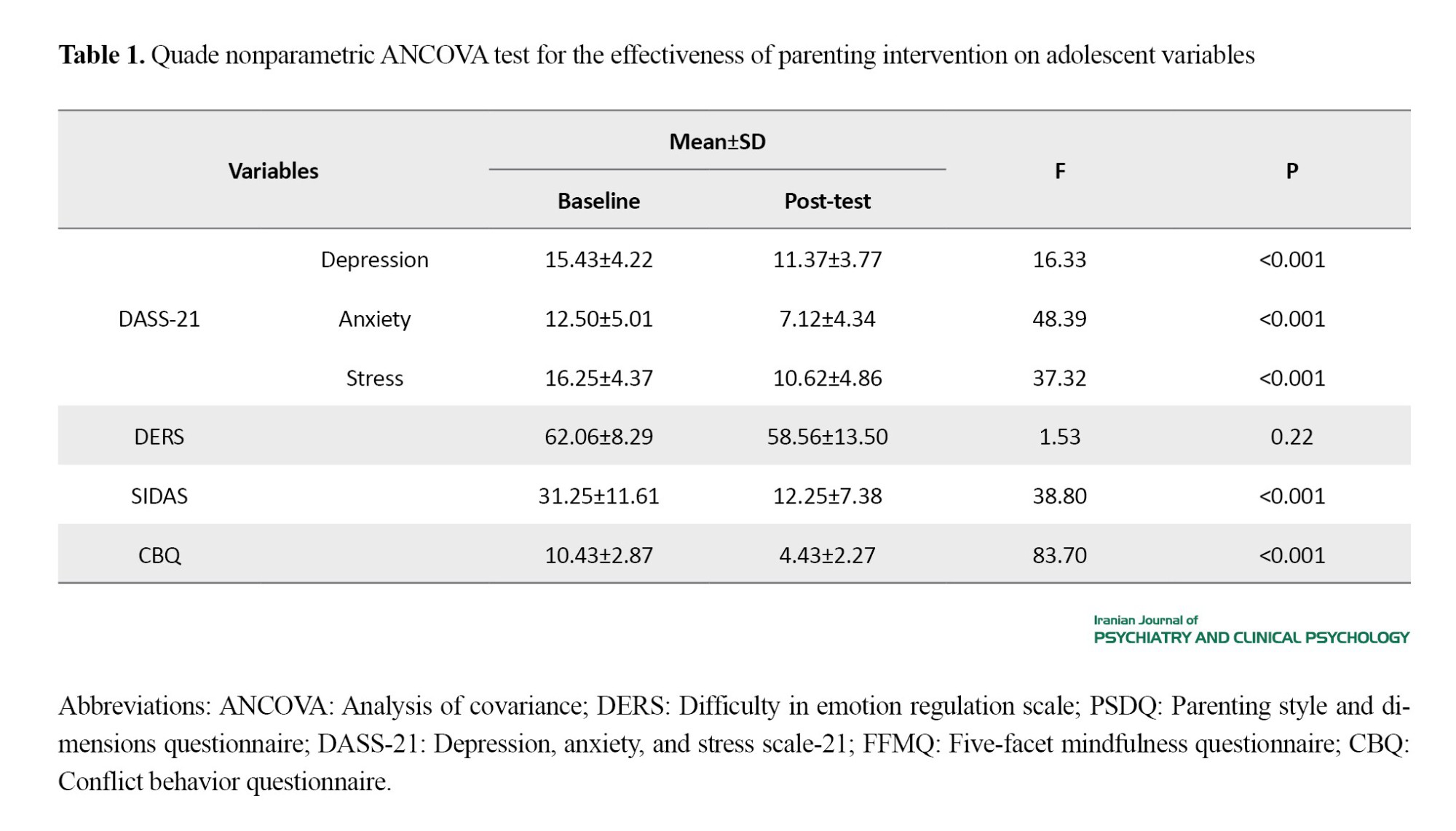

Participants of the experimental group reported no suicide attempt or NSSI, and only one uncompleted attempt and three NNSI cases were reported in the control group of adolescents. The results of quade nonparametric ANCOVA for the parent group showed that the observed differences in the averages of parenting styles (increasing the scores of authoritative parenting style and decreasing the scores of authoritarian parenting style), mindfulness (total score and components of observation, acting with awareness, non-judgment and non-reaction), DASS-21 (depression, stress) and caregiver strain between the two experimental and control groups are statistically significant. Also, the mentioned test was statistically significant for the DASS-21 variables (depression and anxiety, stress), SIDAS (suicide risk), and conflict behavior with the parent for the adolescent group. Still, there were no significant differences in the components of DERS of adolescents and permissive parenting style and anxiety score of primary caregivers compared to control groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Conclusion

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of a DBT-based parenting intervention on primary caregivers of adolescents with self-harm behaviors. The results showed that the current parenting intervention was associated with reducing the stress and depression symptoms of primary caregivers, increasing the score related to authoritative parenting, and reducing the burden of strain on caregivers. Also, even though adolescents did not receive any intervention, their CBQ, SIDAS, and DASS-21 scores decreased significantly from the baseline to the end of the intervention. Reducing the symptoms of depression and stress, as well as increasing the mindfulness of parents in this study, are completely aligned with the skills and rules that are included in this intervention. For example, learning to have a dialectical and non-judgmental position towards themselves and their adolescents and using behavioral management skills to reduce behavioral problems can explain the observed changes. Also, learning how to make decisions using a wise mind versus an emotional mind, practicing mindfulness, and increasing the validation of themselves and their adolescents causes them to have more control over their responses to their adolescents.

The present study is the first to investigate the effectiveness of a DBT-based parenting intervention therapy with a control group. However, the findings of each research study should be considered, along with its limitations. Among the limitations of the current research, we can mention the small size of the sample and the selection of participants from Tehran Province, making it difficult to generalize the findings to larger populations. The other limitation is the participation of one parent in the study. Therefore, it is recommended that future research overcome the limitations of the current study by increasing the size and diversity of the sample and implementing the intervention for both parents. Also, in the field of statistical analysis, future studies are suggested to identify the exact mediating mechanisms and paths through which the DBT-based parenting intervention has led to the mentioned changes in adolescents using the mediation analysis method.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Before the study, a written informed consent was obtained from the parents. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1402.007), and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20201009048974N6).

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD thesis of Fatemeh Nazari at the Department of Clinical Psychology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, writing, validation, and investigation, validation: Fatemeh Nazari; Supervision, review & editing: Maryam Bakhtiyari, Amir Sam Kianimoghadam, Banafshe Mohajerin, and Mahdieh Golestanifard; Methodology: Hojatollah Farahani.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their support, and all participants for their cooperation in the study.

Self-harm refers to intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, regardless of suicidal motive or level of suicidal intent [1], which is often used as a coping mechanism to resolve a difficult situation and can have functions such as emotion regulation, pain level regulation, or self-punishment [2]. Self-harm is a broader concept that includes some degrees of intentionality and ranges from suicidal attempts to non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) [3]. Adolescent self-harm is a leading public health problem. The results of a study that was conducted on the high schools of the north of Iran show that the prevalence of self-harm was 54.9% (20.3% in females and 79.7% in males) [5]. Currently, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is the only format of psychotherapy that has been confirmed to decrease self-harm in adolescents [9]. However, in a study conducted in Norway, the mean number of self-harm behaviors during a 19-week treatment and the one-year follow-up period was 9 and 5.5, respectively, indicating that some participants continued to self-harm even when they were receiving treatment [7, 11]. Therefore, it seems that there is a need to increase the effectiveness of DBT for adolescents.

The results of the studies indicate that parenting styles play a major role in the formation and continuation of psychological problems of children and adolescents [12]. Since DBT is a treatment with strong evidence for improving emotion regulation, researchers have begun to examine how it can not only enhance psychopathology in adult patients but also improve parenting skills toward the goal of reducing psychopathology of adolescents [15]. In this regard, Berk et al. designed a parent-only DBT-based parenting intervention using the “walking the middle path skills” module from the DBT Skills Manual for Adolescents. This intervention is used as individual sessions for parents to provide the possibility of in-depth training of skills as well as implementation according to the special needs of each family [6].

Methods

The present study is a randomized clinical trial. The study inclusion criteria were as follows: Being 11-18 years old for adolescents and 30-50 years old for primary caregivers, the adolescent has attempted suicide or NSSI at least once in the past 3 months, having at least a high school diploma for the primary caregiver and not receiving any simultaneous treatment (psychological and pharmaceutical) by caregivers and adolescents. According to the inclusion criteria, 32 pairs (primary caregiver and adolescent) referred by a psychiatrist at Luqman Hospital through convenience sampling were randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups. Adolescents did not receive any treatment as part of the study. The caregivers in the experimental group received an 8-session parenting intervention by a PhD student in clinical psychology under supervision.

The participants who were in the control group were placed on the waiting list and received DBT-based parenting intervention from another therapist after completing the study. Both parents were encouraged to attend the sessions. However, if both parents could not attend, one parent was allowed to participate. The data were collected from both caregivers and adolescents at the baseline and post-test phases using the difficulty in emotion regulation scale (DERS); parenting style and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ); depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21); five-facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ); conflict behavior questionnaire (CBQ); and caregiver strain questionnaire-short form 11 (CGSQ-SF11). Then the obtained data were analyzed at descriptive and inferential levels. In the descriptive section, indicators such as mean and standard deviation were reported. Also, the assumptions of the covariance test (homogeneity of variances) were examined to analyze the main relationships between groups. However, the relevant tests were all significant in the present study, so the quade nonparametric analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze the dependent variables. The significance level in all the above cases is 0.05, and all analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 27.

Results

The results related to the demographic characteristics of the participants showed that the average age in the experimental group was 15.31 in adolescents and 41.43 in primary caregivers. Also, the average age in the adolescent control group was 15.43 and 41.75 in the primary caregivers. About 50% of adolescents in both experimental and control groups had a history of NSSI. Also, 100% of adolescents in the control and experimental groups attempted suicide, but 23.5% of participants in the experimental group and 31.3% of the control group reported previous suicide attempts.

Participants of the experimental group reported no suicide attempt or NSSI, and only one uncompleted attempt and three NNSI cases were reported in the control group of adolescents. The results of quade nonparametric ANCOVA for the parent group showed that the observed differences in the averages of parenting styles (increasing the scores of authoritative parenting style and decreasing the scores of authoritarian parenting style), mindfulness (total score and components of observation, acting with awareness, non-judgment and non-reaction), DASS-21 (depression, stress) and caregiver strain between the two experimental and control groups are statistically significant. Also, the mentioned test was statistically significant for the DASS-21 variables (depression and anxiety, stress), SIDAS (suicide risk), and conflict behavior with the parent for the adolescent group. Still, there were no significant differences in the components of DERS of adolescents and permissive parenting style and anxiety score of primary caregivers compared to control groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Conclusion

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of a DBT-based parenting intervention on primary caregivers of adolescents with self-harm behaviors. The results showed that the current parenting intervention was associated with reducing the stress and depression symptoms of primary caregivers, increasing the score related to authoritative parenting, and reducing the burden of strain on caregivers. Also, even though adolescents did not receive any intervention, their CBQ, SIDAS, and DASS-21 scores decreased significantly from the baseline to the end of the intervention. Reducing the symptoms of depression and stress, as well as increasing the mindfulness of parents in this study, are completely aligned with the skills and rules that are included in this intervention. For example, learning to have a dialectical and non-judgmental position towards themselves and their adolescents and using behavioral management skills to reduce behavioral problems can explain the observed changes. Also, learning how to make decisions using a wise mind versus an emotional mind, practicing mindfulness, and increasing the validation of themselves and their adolescents causes them to have more control over their responses to their adolescents.

The present study is the first to investigate the effectiveness of a DBT-based parenting intervention therapy with a control group. However, the findings of each research study should be considered, along with its limitations. Among the limitations of the current research, we can mention the small size of the sample and the selection of participants from Tehran Province, making it difficult to generalize the findings to larger populations. The other limitation is the participation of one parent in the study. Therefore, it is recommended that future research overcome the limitations of the current study by increasing the size and diversity of the sample and implementing the intervention for both parents. Also, in the field of statistical analysis, future studies are suggested to identify the exact mediating mechanisms and paths through which the DBT-based parenting intervention has led to the mentioned changes in adolescents using the mediation analysis method.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Before the study, a written informed consent was obtained from the parents. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1402.007), and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20201009048974N6).

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD thesis of Fatemeh Nazari at the Department of Clinical Psychology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, writing, validation, and investigation, validation: Fatemeh Nazari; Supervision, review & editing: Maryam Bakhtiyari, Amir Sam Kianimoghadam, Banafshe Mohajerin, and Mahdieh Golestanifard; Methodology: Hojatollah Farahani.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their support, and all participants for their cooperation in the study.

References

- Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet. 2012; 379(9834):2373-82. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5] [PMID]

- Morken IS, Dahlgren A, Lunde I, Toven S. The effects of interventions preventing self-harm and suicide in children and adolescents: An overview of systematic reviews. F1000Research. 2019; 8:890. [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.19506.1] [PMID]

- Rogers J, Chesney E, Oliver D, Begum N, Saini A, Wang S, et al. Suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm in infectious disease epidemics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2021; 30:e32. [DOI:10.1017/S2045796021000354]

- Collaboration G. Global and national burden of diseases and injuries among children and adolescents between 1990 and 2013: findings from the global burden of disease 2013 study. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016; 170(3):267. [DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4276] [PMID]

- Abdollahi E, Kousha M, Bozorgchenani A, Bahmani M, Rafiei E, Eslamdoust-Siahestalkhi F. Prevalence of self-harm behaviors and deliberate self-cutting in high school students in Northern Iran and its relationship with anxiety, depression, and stress. Journal of Holistic Nursing And Midwifery. 2022; 32(3):169-77. [DOI:10.32598/jhnm.32.3.2193]

- Berk MS, Rathus J, Kessler M, Clarke S, Chick C, Shen H, et al. Pilot test of a DBT-based parenting intervention for parents of youth with recent self-harm. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2022; 29(2):348-66. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.10.001]

- McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, Adrian M, Cohen J, Korslund K, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018; 75(8):777-85. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109] [PMID]

- Rathus JH, Miller AL. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2002; 32(2):146-57. [DOI:10.1521/suli.32.2.146.24399] [PMID]

- Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, Haga E, Diep LM, Laberg S, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014; 53(10):1082-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003] [PMID]

- Zalewski M, Lewis JK, Martin CG. Identifying novel applications of dialectical behavior therapy: Considering emotion regulation and parenting. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2018; 21:122-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.013] [PMID]

- Tebbett-Mock AA, Saito E, McGee M, Woloszyn P, Venuti M. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy versus treatment as usual for acute-care inpatient adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020; 59(1):149-56. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.01.020] [PMID]

- Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, Haga E, Diep LM, Stanley BH, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: Outcomes over a one-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016; 55(4):295-300. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.005] [PMID]

- Cole DA, Sinclair-McBride KR, Zelkowitz R, Bilsk SA, Roeder K, Spinelli TJJoCC, et al. Peer victimization and harsh parenting predict cognitive diatheses for depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2016; 45(5):668-80. [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2015.1004679] [PMID]

- Wedig MM, Nock MK. Parental expressed emotion and adolescent self-injury. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007; 46(9):1171-8. [DOI:10.1097/chi.0b013e3180ca9aaf] [PMID]

- Polk E, Liss M. Psychological characteristics of self-injurious behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007; 43(3):567-77. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2007.01.003]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Link]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Link]

- Fruzzetti AE, Iverson KM. Intervening with couples and families to treat emotion dysregulation and psychopathology. In: Snyder DK, Simpson J, Hughes JN, editors. Emotion regulation in couples and families: Pathways to dysfunction and health. New York: American Psychological Association; 2006. [DOI:10.1037/11468-012]

- Crandall A, Deater-Deckard K, Riley AW. Maternal emotion and cognitive control capacities and parenting: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review. 2015; 36:105-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.dr.2015.01.004] [PMID]

- Zalewski M, Goodman SH, Cole PM, McLaughlin KA. Clinical considerations when treating adults who are parents. Clinical Psychology. 2017; 24(4):370. [DOI:10.1037/h0101745] [PMID]

- Berk M. Evidence-based treatment approaches for suicidal adolescents: Translating science into practice. Washington: American Psychiatric Pub; 2019. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9781615379125]

- Eyden J, Winsper C, Wolke D, Broome MR, MacCallum F. A systematic review of the parenting and outcomes experienced by offspring of mothers with borderline personality pathology: Potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016; 47:85-105. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.002] [PMID]

- Fergus TA, Bardeen JR. Emotion regulation and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A further examination of associations. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2014; 3(3):243-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.06.001]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004; 26(1):41-54. [DOI:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94]

- Khanzadeh M, Saeediyan M, Hosseinchari M, Edrissi F. Factor structure and psychometric properties of difficulties in emotional regulation scale. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 6(1):87-96. [Link]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ). Psycholo gical Repo rts. 1995; 77:819-30. [Link]

- Aghajanzadeh Goodarzi M, Dehestani M. Parenting methods (PSDQ) in parents of children 7-11 years old in Mazandaran province. Paper presented at: Second International Conference on Psychology, Counseling and Educational Sciences 2019. 2019 October 31; Tehran, Iran. [Link]

- Thapa DK, Visentin D, Kornhaber R, Cleary M. Psychometric properties of the Nepali language version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS‐21). Nursing Open. 2022; 9(6):2608-17. [DOI:10.1002/nop2.959] [PMID]

- Khademian F, Delavari S, Koohjani Z, Khademian Z. An investigation of depression, anxiety, and stress and its relating factors during COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):1-7. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10329-3] [PMID]

- Carpenter JK, Conroy K, Gomez AF, Curren LC, Hofmann SG. The relationship between trait mindfulness and affective symptoms: A meta-analysis of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Clinical psychology review. 2019; 74:101785. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101785] [PMID]

- Heydarinasab L. An investigation of the validity and reliability of psychometric characteristics of five facet mindfulness questionnaire in Iranian non-clinical samples. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 7(3):229-37. [Link]

- Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, Bickman L. The caregiver strain questionnaire: Measuring the impact on the family of living with a child with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of emotional and behavioral disorders. 1997; 5(4):212-22. [DOI:10.1177/106342669700500404]

- Brennan GM, Babinski DE, Waschbusch DA. Caregiver Strain Questionnaire-Short Form 11 (CGSQ-SF11): A validation study. Assessment. 2022; 29(7):1351-70. [DOI:10.1177/10731911211015360] [PMID]

- Harris K, Haddock G, Peters S, Gooding P. Psychometric properties of the Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale (SIDAS) in a longitudinal sample of people experiencing non-affective psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2021; 21(1):628. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-021-03639-8] [PMID]

- Flynn D, Gillespie C, Joyce M, Spillane A. An evaluation of the skills group component of DBT-A for parent/guardians: A mixed methods study. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2023; 40(2):143-51. [DOI:10.1017/ipm.2019.62] [PMID]

- Burešová I, Bartošová K, Čerňák MJP-s, sciences b. Connection between parenting styles and self-harm in adolescence. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015; 171:1106-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.272]

- Cartwright‐Hatton S, Ewing D, Dash S, Hughes Z, Thompson EJ, Hazell CM, et al. Preventing family transmission of anxiety: Feasibility RCT of a brief intervention for parents. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2018; 57(3):351-66. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12177] [PMID]

- Sim WH, Fernando LMN, Jorm AF, Rapee RM, Lawrence KA, Mackinnon AJ, et al. A tailored online intervention to improve parenting risk and protective factors for child anxiety and depression: Medium-term findings from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020; 277:814-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.019] [PMID]

- Burešová I, Bartošová K, Čerňák M. Connection between parenting styles and self-harm in adolescence. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015; 171:1106-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.272]

- Michelson D, Davenport C, Dretzke J, Barlow J, Day C. Do evidence-based interventions work when tested in the “real world?” A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent management training for the treatment of child disruptive behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2013; 16(1):18-34. [DOI:10.1007/s10567-013-0128-0] [PMID]

- Reading R. The clinical effectiveness of different parenting programmes for children with conduct problems: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Child; 2009; 35(4):589-90. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00987_6.x]

- Lundahl B, Risser HJ, Lovejoy MC. A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006; 26(1):86-104. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004] [PMID]

- Vasilevska Petrovska I, Trajkovski V. Effects of a computer-based intervention on emotion understanding in children with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019; 49(10):4244-55. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-019-04135-5] [PMID]

- You S, Lim SA. Development pathways from abusive parenting to delinquency: The mediating role of depression and aggression. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015; 46:152-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.009] [PMID]

- Kingsbury M, Sucha E, Manion I, Gilman SE, Colman I. Adolescent mental health following exposure to positive and harsh parenting in childhood. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020; 65(6):392-400. [DOI:10.1177/0706743719889551] [PMID]

- Latina D, Stattin H. Adolescents who self‐harm: The patterns in their interpersonal and psychosocial difficulties. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2018; 28(4):824-38. [DOI:10.1111/jora.12368] [PMID]

- Swearer SM, Hymel S. Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. American Psychologist. 2015; 70(4):344. [DOI:10.1037/a0038929] [PMID]

- Adrian M, Zeman J, Erdley C, Lisa L, Sim L. Emotional dysregulation and interpersonal difficulties as risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011; 39:389-400. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-010-9465-3] [PMID]

- Baetens I, Claes L, Hasking P, Smits D, Grietens H, Onghena P, et al. The relationship between parental expressed emotions and non-suicidal self-injury: The mediating roles of self-criticism and depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015; 24:491-8. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-013-9861-8]

- Parent J, Garai E, Forehand R, Roland E, Potts J, Haker K, et al. Parent mindfulness and child outcome: The roles of parent depressive symptoms and parenting. Mindfulness. 2010; 1(4):254-64. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-010-0034-1] [PMID]

- Bögels SM, Hellemans J, van Deursen S, Romer M, van der Meulen R. Mindful parenting in mental health care: effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, coparenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness. 2014; 5(5):536-51. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-013-0209-7]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Gayles JG, Bamberger KT, et al. Integrating mindfulness with parent training: effects of the Mindfulness-Enhanced Strengthening Families Program. Developmental Psychology. 2015; 51(1):26. [DOI:10.1037/a0038212] [PMID]

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Laboratory stressors in clinically anxious and non-anxious individuals: The moderating role of mindfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010; 48(6):495-505. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2010.02.005] [PMID]

- Erisman SM, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the effects of experimentally induced mindfulness on emotional responding to film clips. Emotion. 2010; 10(1):72. [DOI:10.1037/a0017162] [PMID]

- Hill CL, Updegraff JA. Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion. 2012; 12(1):81. [DOI:10.1037/a0026355] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2024/09/15 | Accepted: 2025/04/16 | Published: 2025/08/1

Received: 2024/09/15 | Accepted: 2025/04/16 | Published: 2025/08/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |