Tue, Dec 9, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 30, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2024)

IJPCP 2024, 30(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zolghadri S, Hadavi M, Bahrami Ehsan H. Prevalence of Depression and the Related Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors in the Post-COVID Era: A Population-Based Study in Iran. IJPCP 2024; 30 (1) : 4949.1

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4157-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4157-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Transportation Planning, Faculty of civil engineering, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran. ,hbahrami@ut.ac.ir

2- Department of Transportation Planning, Faculty of civil engineering, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 8009 kb]

(790 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2149 Views)

Full-Text: (1868 Views)

Introduction

Psychological disorders are among one of the main global health concerns. Despite advancements in treatment programs in the past two decades, the prevalence of these disorders is showing an alarming increase [1]. Nearly 970 million people, constituting 12% of the world’s population, suffer from psychological disorders, mostly residing in low- and middle-income countries [2, 3]. Psychological disorders, including depression, contribute substantially to disability-adjusted life years [4]. The COVID-19 pandemic increased the prevalence of depression in people, emphasizing the urgency needed for preventive and intervention measures [5]. A systematic review study revealed a noteworthy surge in the global prevalence of depression, particularly in certain Asian countries, following the COVID-19 outbreak [8]. In Iran, various studies have shown varying depression prevalence rates, with higher rates in women and residents of rural areas and small towns [13]. The studies conducted after the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran have reported a surge in depression prevalence, especially among specific demographic groups [14-20]. There is a lack of information regarding the current state of mental health in the Iranian community. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the prevalence of depression and the associated demographic and socio-economic factors among people aged ≥15 years in Iran.

Methods

This is a descriptive-analytical population-based study that was conducted from February to April 2023. Based on the 2015 national population and housing census [23], the study population consists of all Iranian citizens aged 15 and older (n=60,733,605). The sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula, which was 3,018, considering a 10% sample dropout. A multistage stratified sampling approach was adopted for recruiting samples from different provinces based on the inclusion criteria (residency in Iran, verbal communication ability to respond to the questions, age ≥15, and voluntary informed consent). Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to continue the interview and giving incomplete answers.

The information was collected through telephone interviews using the Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) system. Questionnaires were used for data collection, including demographic and socioeconomic factors and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation were computed in SPSS software, version 21. Hypotheses were tested using Welch’s t-test and logistic regression analysis. The significant impact of independent variables on the dependent variable was examined using the Wald test and likelihood ratio test in the “lmtest” package in R software. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 3,018 individuals who participated in the interviews, 126 were excluded due to incomplete responses. Therefore, the analysis was done on 2,892 respondents. Their mean age was 43.6±16.9 years (42.6 for women and 44.7 for men). Utilizing the PHQ-2 tool and based on a cut-off point of 3, the study revealed that 1,218 people (42.1%) had clinical depression symptoms, while 1,674 people (57.9%) did not manifest depression symptoms. The depression prevalence rate was 44.6% for women and 39.6% for men, with mean depression scores of 2.52±1.71 and 2.25±1.83, respectively.

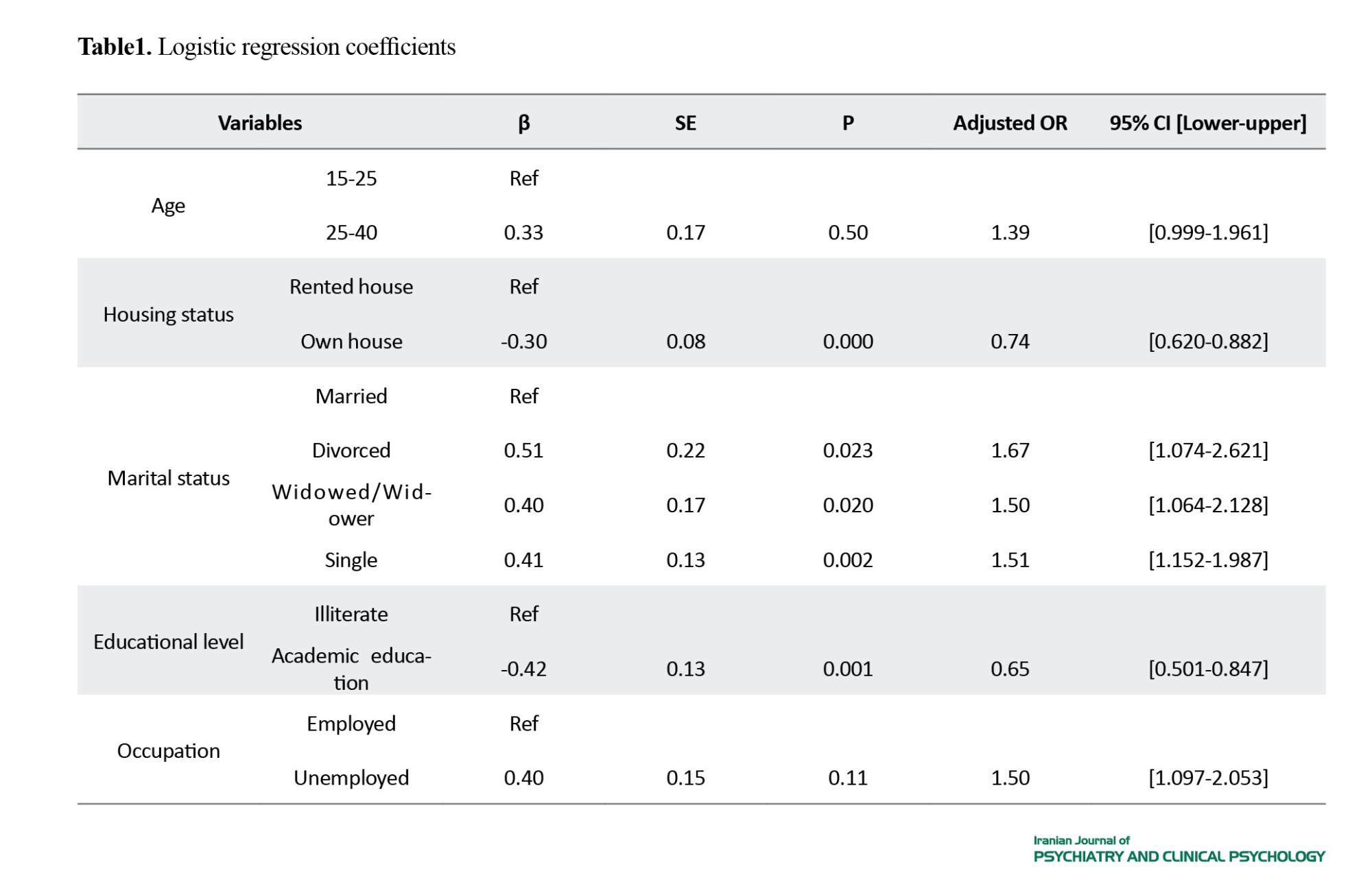

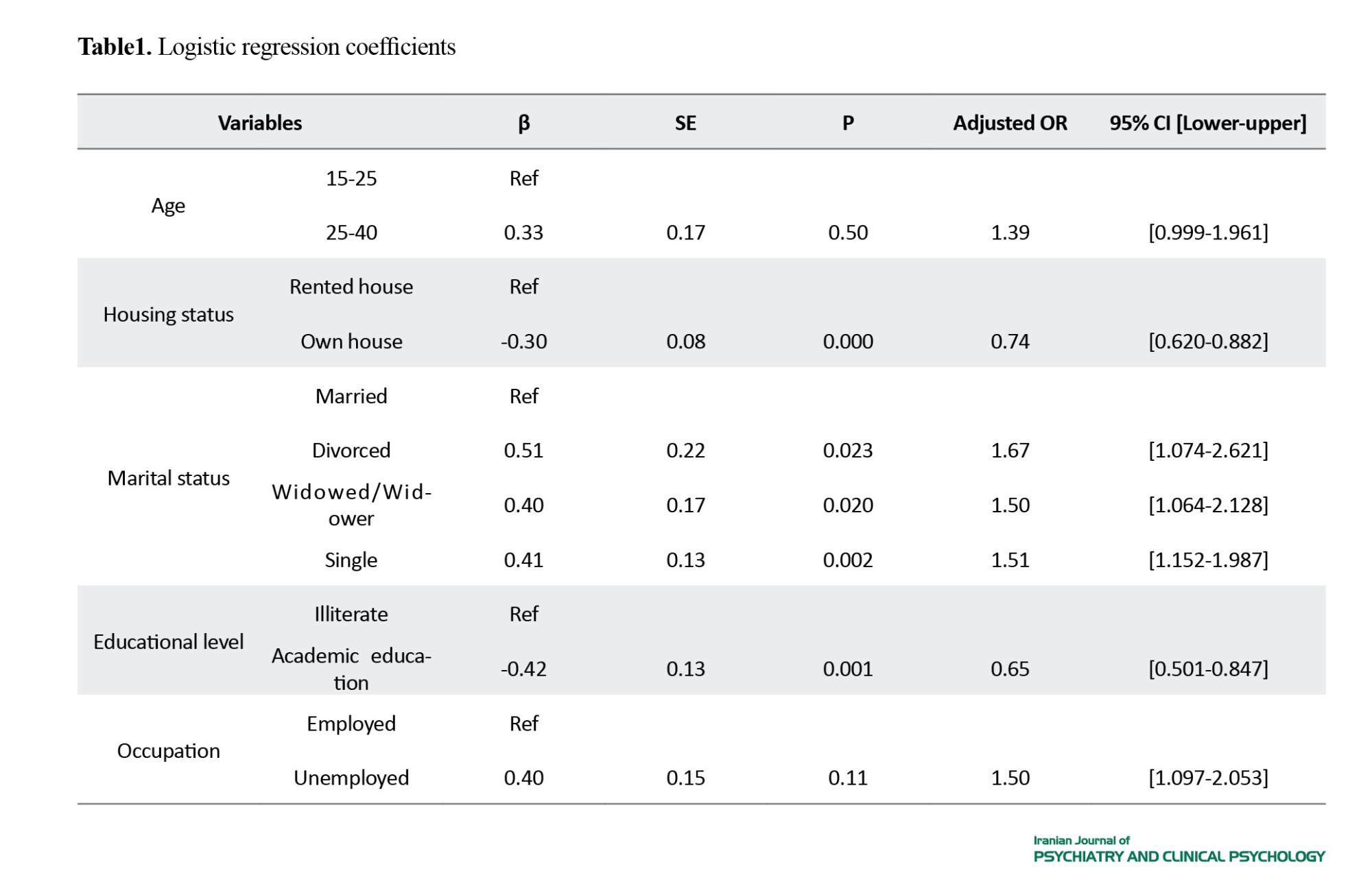

We analyzed the predictors of depression using the multiple logistic regression model, including gender, education, age, place of residence, marital status, income, and housing status. The findings revealed that housing status (β=-0.30, OR=0.74, P=0.000), being single (β=0.41, OR=1.51, P=0.002), being widowed/widower (β=0.40, OR=1.50, P=0.020), being divorced (β=0.51, OR=1.67, P=0.023), having an academic degree (β=-0.42, OR=0.65, P=0.001), unemployment (β=0.40, OR=1.50, P=0.011), age 25-40 (β=0.33, OR=1.39, P=0.050), and being a homeowner (β=-0.30, OR=0.74, P=0.001) had significant associations with depression (Table 1).

Conclusion

In this study, it was found that 42% of Iranian people had major depressive disorder. This prevalence indicates a high number of individuals experiencing depression, but due to the relatively low predictive value of 3 as the cut-off point of the PHQ-2 [32], there may be a potential for overestimation. Although women showed higher depression rates, the gender factor was omitted from the multivariate regression model, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive approach beyond gender. The 25-40 age group exhibited marginally higher depression rates than the age group 15-25. No significant association between place of residence (rural/urban) and depression prevalence was observed. Education emerged as a protective factor, where people with a university education shower lower depression rates. Unemployment was associated with higher depression prevalence, underscoring the psychosocial impact of economic instability. Marital status played a significant role, where single, divorced, and widowed/widower individuals experienced higher depression rates than married people. The people with an income level of 8-10 million Tomans showed significantly lower depression rates. However, the income level was omitted from the multivariate regression model. This study provides valuable insights into post-COVID depression prevalence in Iran. The nuanced relationships between depression and some demographic and socio-economic factors underscore the importance of comprehensive, multivariate analyses in understanding mental health dynamics.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical considerations were considered in this study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education, University of Tehran (Code: IR.UT.PSYEDU.REC.1403.003).

Funding

This study was funded by the Strategic Center for Culture and Media in Tehran, Iran.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and original draft preparation: Soroush Zolghadri; Methodology, data collection, and Formal Analysis: Majid Hadavi; Editing and supervision: Hadi Bahrami Ehsan.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Strategic Center for Culture and Media and the University of Tehran for their support and all the individuals who participated in this study for their cooperation.

Psychological disorders are among one of the main global health concerns. Despite advancements in treatment programs in the past two decades, the prevalence of these disorders is showing an alarming increase [1]. Nearly 970 million people, constituting 12% of the world’s population, suffer from psychological disorders, mostly residing in low- and middle-income countries [2, 3]. Psychological disorders, including depression, contribute substantially to disability-adjusted life years [4]. The COVID-19 pandemic increased the prevalence of depression in people, emphasizing the urgency needed for preventive and intervention measures [5]. A systematic review study revealed a noteworthy surge in the global prevalence of depression, particularly in certain Asian countries, following the COVID-19 outbreak [8]. In Iran, various studies have shown varying depression prevalence rates, with higher rates in women and residents of rural areas and small towns [13]. The studies conducted after the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran have reported a surge in depression prevalence, especially among specific demographic groups [14-20]. There is a lack of information regarding the current state of mental health in the Iranian community. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the prevalence of depression and the associated demographic and socio-economic factors among people aged ≥15 years in Iran.

Methods

This is a descriptive-analytical population-based study that was conducted from February to April 2023. Based on the 2015 national population and housing census [23], the study population consists of all Iranian citizens aged 15 and older (n=60,733,605). The sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula, which was 3,018, considering a 10% sample dropout. A multistage stratified sampling approach was adopted for recruiting samples from different provinces based on the inclusion criteria (residency in Iran, verbal communication ability to respond to the questions, age ≥15, and voluntary informed consent). Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to continue the interview and giving incomplete answers.

The information was collected through telephone interviews using the Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) system. Questionnaires were used for data collection, including demographic and socioeconomic factors and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation were computed in SPSS software, version 21. Hypotheses were tested using Welch’s t-test and logistic regression analysis. The significant impact of independent variables on the dependent variable was examined using the Wald test and likelihood ratio test in the “lmtest” package in R software. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 3,018 individuals who participated in the interviews, 126 were excluded due to incomplete responses. Therefore, the analysis was done on 2,892 respondents. Their mean age was 43.6±16.9 years (42.6 for women and 44.7 for men). Utilizing the PHQ-2 tool and based on a cut-off point of 3, the study revealed that 1,218 people (42.1%) had clinical depression symptoms, while 1,674 people (57.9%) did not manifest depression symptoms. The depression prevalence rate was 44.6% for women and 39.6% for men, with mean depression scores of 2.52±1.71 and 2.25±1.83, respectively.

We analyzed the predictors of depression using the multiple logistic regression model, including gender, education, age, place of residence, marital status, income, and housing status. The findings revealed that housing status (β=-0.30, OR=0.74, P=0.000), being single (β=0.41, OR=1.51, P=0.002), being widowed/widower (β=0.40, OR=1.50, P=0.020), being divorced (β=0.51, OR=1.67, P=0.023), having an academic degree (β=-0.42, OR=0.65, P=0.001), unemployment (β=0.40, OR=1.50, P=0.011), age 25-40 (β=0.33, OR=1.39, P=0.050), and being a homeowner (β=-0.30, OR=0.74, P=0.001) had significant associations with depression (Table 1).

Conclusion

In this study, it was found that 42% of Iranian people had major depressive disorder. This prevalence indicates a high number of individuals experiencing depression, but due to the relatively low predictive value of 3 as the cut-off point of the PHQ-2 [32], there may be a potential for overestimation. Although women showed higher depression rates, the gender factor was omitted from the multivariate regression model, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive approach beyond gender. The 25-40 age group exhibited marginally higher depression rates than the age group 15-25. No significant association between place of residence (rural/urban) and depression prevalence was observed. Education emerged as a protective factor, where people with a university education shower lower depression rates. Unemployment was associated with higher depression prevalence, underscoring the psychosocial impact of economic instability. Marital status played a significant role, where single, divorced, and widowed/widower individuals experienced higher depression rates than married people. The people with an income level of 8-10 million Tomans showed significantly lower depression rates. However, the income level was omitted from the multivariate regression model. This study provides valuable insights into post-COVID depression prevalence in Iran. The nuanced relationships between depression and some demographic and socio-economic factors underscore the importance of comprehensive, multivariate analyses in understanding mental health dynamics.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical considerations were considered in this study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education, University of Tehran (Code: IR.UT.PSYEDU.REC.1403.003).

Funding

This study was funded by the Strategic Center for Culture and Media in Tehran, Iran.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and original draft preparation: Soroush Zolghadri; Methodology, data collection, and Formal Analysis: Majid Hadavi; Editing and supervision: Hadi Bahrami Ehsan.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Strategic Center for Culture and Media and the University of Tehran for their support and all the individuals who participated in this study for their cooperation.

References

- World Health Organization. Mental health Atlas 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). Washington: Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2021. [Link]

- World Health Organization. Global health estimates: Leading causes of DALYs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Link]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2022; 9(2):137-50. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3] [PMID]

- Shahriarirad R, Erfani A, Ranjbar K, Bazrafshan A, Mirahmadizadeh A. The mental health impact of COVID-19 outbreak: A Nationwide Survey in Iran. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2021; 15(1):19. [DOI:10.1186/s13033-021-00445-3] [PMID]

- Wang L, Nabi G, Zuo L, Wu Y, Li D. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and potential solutions in different members in an Ordinary Family Unit. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022; 12:735653. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.735653] [PMID]

- Buczak-Stec EW, Löbner M, Stein J, Stark A, Kaduszkiewicz H, Werle J, et al. Depressive symptoms and healthcare utilization in late life. Longitudinal evidence from the AgeMooDe Study. Frontiers in Medicine. 2022; 9:924309. [DOI:10.3389/fmed.2022.924309] [PMID]

- Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, Lasheras I, López-Antón R, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2021; 21(1):100196. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.07.007] [PMID]

- Tahan M, Saleem T, Zygoulis P, Pires LVL, Pakdaman M, Taheri H, et al. A systematic review of prevalence of depression in Iranian patients. Neuropsychopharmacologia Hungarica. 2020; 22(1):16-22. [PMID]

- Rafiei S, Pashazadeh Kan F, Raoofi S, Masoumi M, Elahifar O, Doustmehraban M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression and anxiety in the Middle East during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Journal of Health Sciences & Surveillance System. 2023; 11(1 (Supplement)):116-25. [DOI:10.30476/jhsss.2022.93838.1482]

- Noorbala AA, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Yasamy MT, Mohammad K. Mental health survey of the adult population in Iran. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004; 184:70-3. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.184.1.70] [PMID]

- Noorbala AA, Faghihzadeh S, Kamali K, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Hajebi A, Mousavi MT, et al. Mental health survey of the Iranian adult population in 2015. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2017; 20(3):128-34. [PMID]

- Noorbala AA, Maleki A, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Faghihzadeh E, Hoseinzadeh Z, Hajibabaei M, et al. Survey on mental health status in Iranian population aged 15 and above one year after the outbreak of COVID-19 disease: A population-based study. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2022; 25(4):201-8. [PMID]

- Pasha H, Omidvar S, Faramarzi M, Bakhtiari A. Depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD symptoms during the first and second COVID-19 waves: A comparison of elderly, middle-aged, and young people in Iran. BMC Psychiatry. 2023; 23(1):190. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-023-04677-0] [PMID]

- Hassannia L, Taghizadeh F, Moosazadeh M, Zarghami M, Taghizadeh H, Dooki AF, et al. Anxiety and depression in health workers and general population during COVID-19 epidemic in Iran: A web-based cross-sectional study. MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI:10.1101/2020.05.05.20089292]

- Maroufizadeh S, Pourshaikhian M, Pourramzani A, Sheikholeslami F, Moghadamnia MT, Alavi SA. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in the Iranian General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A web-based cross-sectional study. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2022; 17(2):230-9. [PMID]

- Khademian F, Delavari S, Koohjani Z, Khademian Z. An investigation of depression, anxiety, and stress and its relating factors during COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):275. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10329-3] [PMID]

- Vahedian-Azimi A, Moayed MS, Rahimibashar F, Shojaei S, Ashtari S, Pourhoseingholi MA. Comparison of the severity of psychological distress among four groups of an Iranian population regarding COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2020; 20(1):402. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-020-02804-9] [PMID]

- Akbarpour S, Nakhostin-Ansari A, Sadeghniiat Haghighi K, Etesam F, Alemohammad ZB, Aghajani F, et al. COVID-19 fear association with depression, anxiety, and insomnia: A national web-based survey on the general population. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2022; 17(1):24-34. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v17i1.8046] [PMID]

- Salehian R, Jolfaei AG, Naserbakht M, Abdi M. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and General Mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 15(3):e114432. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.114432]

- Bagheri Sheykhangafshe F, Fathi-Ashtiani A. [Psychosocial consequences of the post-coronavirus 2019 (covid-19): Systematic review study (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Psychological Research. 2022; 13(3):53-72. [DOI:10.22059/japr.2022.328657.643939]

- Remes O, Mendes JF, Templeton P. Biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression: A review of recent literature. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(12):1633. [DOI:10.3390/brainsci11121633] [PMID]

- Statistical Center of Iran. [Bureau of Population, Labor and Census, statistical yearbook of the country 2018 (Persian)]. Tehran: Statistical Center of Iran; 2023. [Link]

- Delavar A. [Theoretical and practical foundations of research in humanities and social sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Roshd Publication; 2015. [Link]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care. 2003; 41(11):1284-92. [DOI:10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C] [PMID]

- Manea L, Gilbody S, Hewitt C, North A, Plummer F, Richardson R, et al. Identifying depression with the PHQ-2: A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016; 203:382-95. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.003] [PMID]

- Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, Fiscella K. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007; 55(4):596-602. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01103.x] [PMID]

- Dadfar M, Lester D. Psychometric characteristics of Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) in Iranian psychiatric outpatients. Austin Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2017; 4(1):1059. [Link]

- Ghazisaeedi M, Mahmoodi H, Arpaci I, Mehrdar S, Barzegari S. Validity, reliability, and optimal cut-off scores of the WHO-5, PHQ-9, and PHQ-2 to screen depression among university students in Iran. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2022; 20(3):1824-33. [DOI:10.1007/s11469-021-00483-5] [PMID]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2010; 32(4):345-59. [DOI:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006] [PMID]

- de Lima Osório F, Vilela Mendes A, Crippa JA, Loureiro SR. Study of the discriminative validity of the PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 in a sample of Brazilian women in the context of primary health care. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2009; 45(3):216-27. [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2009.00224.x] [PMID]

- Mitchell AJ, Yadegarfar M, Gill J, Stubbs B. Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: A diagnostic meta-analysis of 40 studies. BJPsych Open. 2016; 2(2):127-38. [DOI:10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.001685] [PMID]

- McGee S. Simplifying likelihood ratios. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002; 17(8):646-9. [DOI:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10750.x] [PMID]

- Choi YK, Johnson WO, Thurmond MC. Diagnosis using predictive probabilities without cut-offs. Statistics in Medicine. 2006; 25(4):699-717. [DOI:10.1002/sim.2365] [PMID]

- Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, Gunn J, Kerse N, Fishman T, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2010; 8(4):348-53. [DOI:10.1370/afm.1139] [PMID]

- Newman TB, Kohn MA. Multilevel and continuous tests. In: Evidence-based diagnosis: An introduction to clinical epidemiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2020.[DOI:10.1017/9781108500111.004]

- Birnbaum MH. Base rates in bayesian inference: Signal detection analysis of the cab problem. The American Journal of Psychology. 1983; 96(1):85-94. [DOI:10.2307/1422211]

- Peng CY, Lee KL, Ingersoll GM. An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. The Journal of Educational Research. 2002; 96(1):3-14. [DOI:10.1080/00220670209598786]

- Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Scientific Reports. 2018; 8(1):2861. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x] [PMID]

- Shuster A, O'Brien M, Luo Y, Berner LA, Perl O, Heflin M, et al. Emotional adaptation during a crisis: Decline in anxiety and depression after the initial weeks of COVID-19 in the United States. Translational Psychiatry. 2021; 11(1):435. [DOI:10.1038/s41398-021-01552-y] [PMID]

- Fancourt D, Steptoe A, Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021; 8(2):141-9. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X] [PMID]

- Bourmistrova NW, Solomon T, Braude P, Strawbridge R, Carter B. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022; 299:118-25. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.031] [PMID]

- Jeong H, Yim HW, Song YJ, Ki M, Min JA, Cho J, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiology and Health. 2016; 38:e2016048. [DOI:10.4178/epih.e2016048] [PMID]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020; 395(10227):912-20. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8] [PMID]

- Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT, Egele-Godswill E, Mbaegbu P. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Science Progress. 2021; 104(2):00368504211019854. [DOI:10.1177/00368504211019854] [PMID]

- Richter D, Wall A, Bruen A, Whittington R. Is the global prevalence rate of adult mental illness increasing? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2019; 140(5):393-407. [DOI:10.1111/acps.13083] [PMID]

- Kim SW, Park IH, Kim M, Park AL, Jhon M, Kim JW, et al. Risk and protective factors of depression in the general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in Korea. BMC Psychiatry. 2021; 21(1):445. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-021-03449-y] [PMID]

- Pawar N, Kumar N, Vikram A, Sembiah S, Rajawat G. Depression and its socio-demographic correlates among urban slum dwellers of North India: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2022; 11(6):2369-76. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_616_21] [PMID]

- Sojasi Qeidari H, Sadeqlou T, Shahdadi A. [The effects of globalization on lifestyle changes in rural areas (Persian)]. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities. 2016; 7(4):153-88. [DOI:10.7508/isih.2015.28.006]

- Purtle J, Nelson KL, Yang Y, Langellier B, Stankov I, Roux AV. Urban-rural differences in older adult depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2019; 56(4):603-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.008] [PMID]

- Xu C, Miao L, Turner D, DeRubeis R. Urbanicity and depression: A global meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2023; 340:299-311. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.030] [PMID]

- Falahat K, Baradaran Eftekhari M, Mirabzadeh A. [Social determinants of health for positive mental health of Iranian adults (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2024; 29(4):494-513. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.29.4.2669.4]

- Hayati M, Soleymani Sh. [The consequences of divorce for the divorced person: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi. 2019; 7(11):273-88. [Link]

- Szabo A, Allen J, Alpass F, Stephens C. Longitudinal trajectories of quality of life and depression by housing tenure status. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2018; 73(8):e165-74. [DOI:10.1093/geronb/gbx028] [PMID]

- Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2005; 58(2):163-71. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2024/04/15 | Accepted: 2024/10/27 | Published: 2024/07/31

Received: 2024/04/15 | Accepted: 2024/10/27 | Published: 2024/07/31

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |