Mon, Feb 2, 2026

| فارسی

Volume 30, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2024)

IJPCP 2024, 30(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zargarani N, Azadfallah P, Farahani H. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of Embodied Sense of Self Scale. IJPCP 2024; 30 (1) : 1899.1

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4066-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4066-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. ,azadfa_p@modares.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 7533 kb]

(1266 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2735 Views)

Full-Text: (908 Views)

Introduction

Most of recent studies in psychology, philosophy and neuroscience have focused on assessing brain representations of the sense of self [1، 2]. Despite numerous objective and experimental studies on the relationship between body and sense of self, its development as a phenomenological whole has received less attention [3]. Consequently, recent studies have concentrated on the concept of embodiment. The embodied sense of self (ESS) refers to subjective feelings grounded within our own body and sensorimotor system [4], evaluated based on multimodal sensory integration [5] or the congruence of motor predictions and actual feedbacks [6].

Theories propose two components of the sense of self including minimal and narrative self. The minimal self is the pre-reflective [7] and pre-linguistic [8] self-awareness of other entities through the body [9-12]. However, the minimal self is insufficient for forming complete representations of the self [2]. The narrative self is a concept developed to address this gap. This social narrative construct, as a form of first-person ownership, relies on the minimal self and is shaped and reconfigured through our efforts to make sense of our evolving experiences [13]. Minimal self is recognized based on sense of self-ownership and self-agency while narrative self is defined by continuity and conformity. The development of ESS is always accompanied by errors that lead to outcomes such as the breakdown of self-other boundaries, dissociation and somatization [14]. These errors not only affect the improvement of psychological disorders in individuals with brain injuries, but also influence their return to normal life [15], potentially increasing the risk of dissociative and psychotic spectrum disorders in the general population.

There are very few tools to measure various dimensions of embodiment. The existing tools often concentrate on a specific group or examine the outcomes of embodiment as an indicator of well-being [19]. The embodied sense of self scale (ESSS) with 25 items and three domains (agency, ownership and narrative), is a tool designed to evaluate the relationship between the body and the sense of self, [2]. The ownership refers to the sense of ownership over the body, possessions, and the self. Its impairment is manifested by depersonalization [16]. Impaired sense of agency is manifested by an inability to manipulate the body, use tools, or perform desired actions, which is observed in the general population and those with schizotypal personality traits, in addition to individuals with schizophrenia [2، 17]. Narrative domain evaluates the temporal continuity and unique nature of the self, which can be seen through bodily movements and actions. Although impaired narrative domain is mainly present in individuals with schizophrenia, it is most seen in those with schizotypal personality traits [2]. The validity assessments of the Italian version of the ESSS revealed that the three-factor model does not adequately fit the Italian samples. Exploratory factor analysis results suggested an alternative model with three factors: self-recognition, self- consistence, and self-awareness [18].

The ESSS is the only tool that focuses on the organization of bodily self in the general population, improvement of the consequences of brain injuries, and prevention of psychotic and dissociative disorders. Moreover, since embodied subjectivity is formed interpersonally, response to others and the cultural context encompass factors such as gender, ethnicity, sex and disability, which always influence bodily perspective and our definition of the self [13]. This has caused different cultures to look at ESS from different perspectives. The present study aims to validate and assess the reliability of the Persian version of ESSS for the Iranian samples.

Methods

This is a psychometrics study. Participants were 215 Iranian people aged 20-65 years (160 females and 55 males, mean age: 34.33±10.81 years), who were selected from those members in social networks (Telegram and WhatsApp). The sample size was determined according to Bentley and Chou’s study [17]. Given that the ESSS has 25 items, the required sample size ranges from 125 to 375. To compensate for sample dropouts, sampling continued until reaching the necessary number of participants. The sampling was done online using a convenience sampling method. The people with age ≥19 years and those who declared consent to participate in the study were included. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate, failure to respond to at least one question, or having a specific response pattern.

The Persian version of the ESSS was prepared after translation and back-translation, and verification of conceptual equivalency of the scales [18]. The original scale was translated into Persian by a PhD student in psychology and an English language specialist. After modification, the translated versions were cross-checked with the English version by a member of the faculty of psychology who was expert in both culture and English. Subsequently, the draft was re-translated into English by an English translator, and the primary author compared it with the main version to confirm consistency. Finally, the Persian version of the ESSS as well as the dissociative experiences scale II (DES-II) and prosocial tendencies measure (PTM) were sent to participants online to complete

Construct validity was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), while convergent validity was evaluated using the average variance extracted (AVE). Pearson correlation test was employed to examine concurrent and divergent validity. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficient. Data analysis was conducted in SPSS sofware, version 27 and R version 4.3.2 Lavaan package

Results

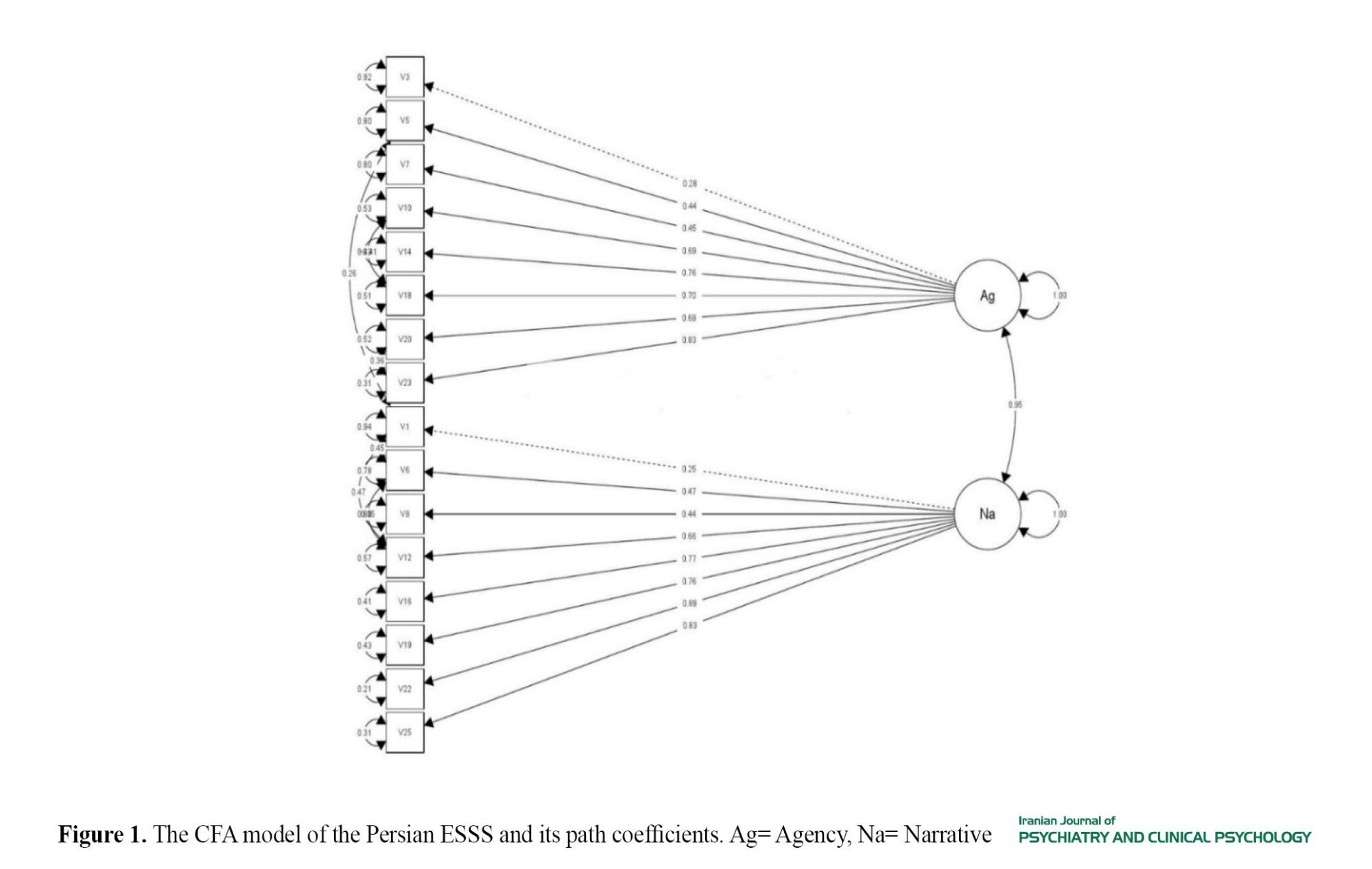

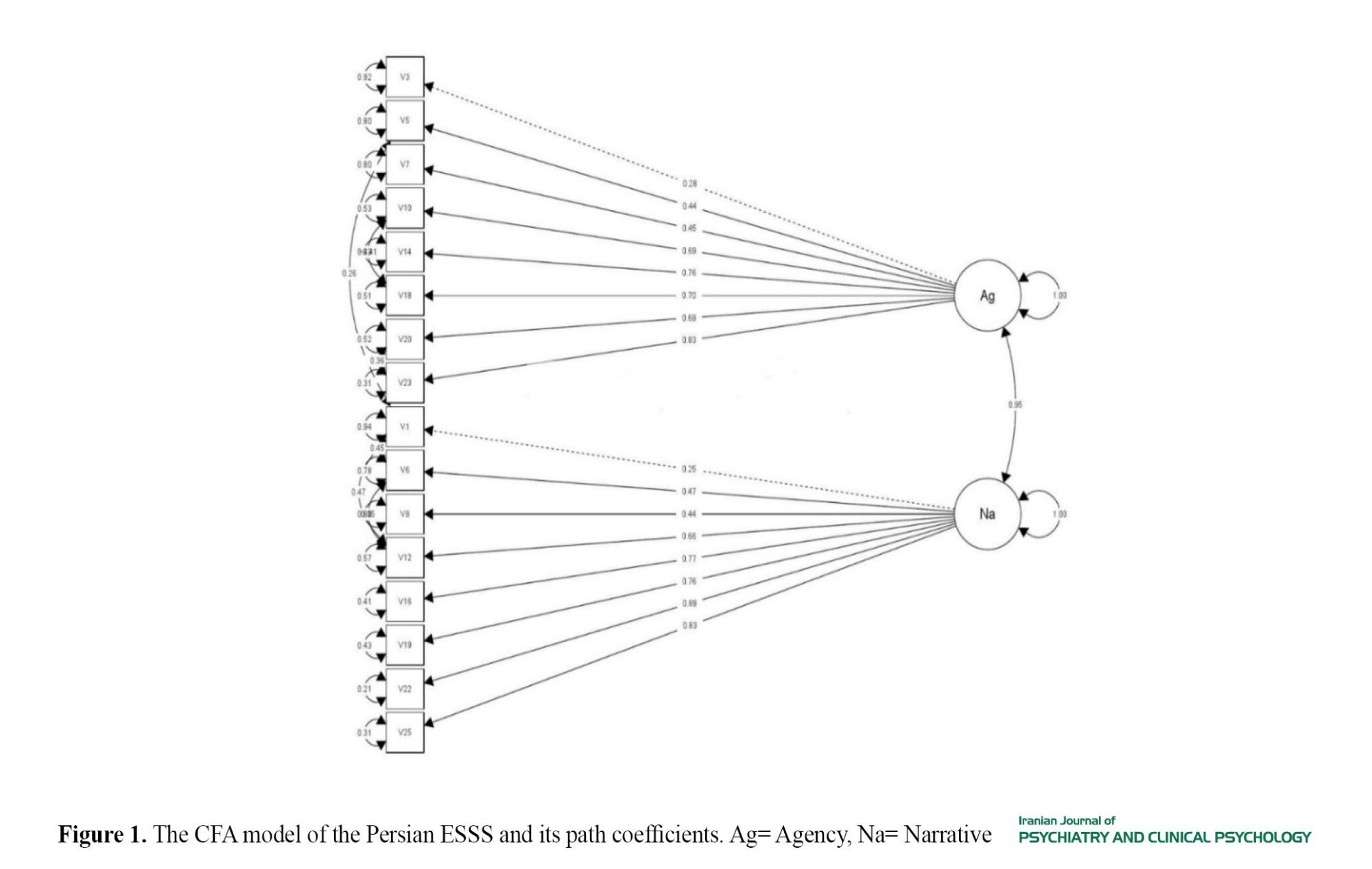

Results of CFA showed that the three-factor solution of the Persian ESSS had an acceptable construct validity but not optimum fit. The items for the ownership subscale were deleted because their factor loads were lower than the acceptable value of 0.4. The final CFA model is shown in Figure 1.

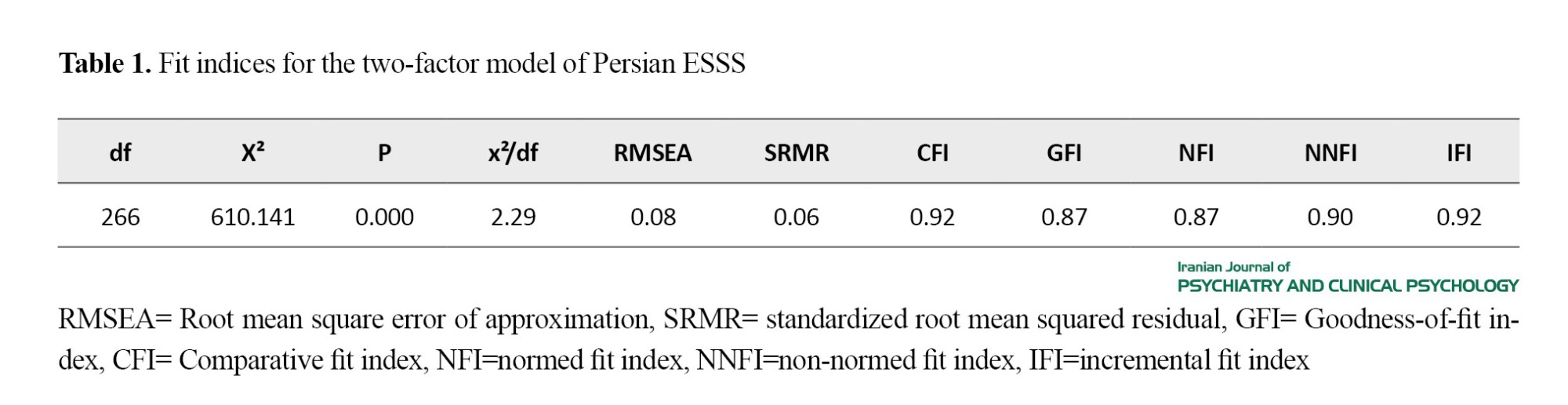

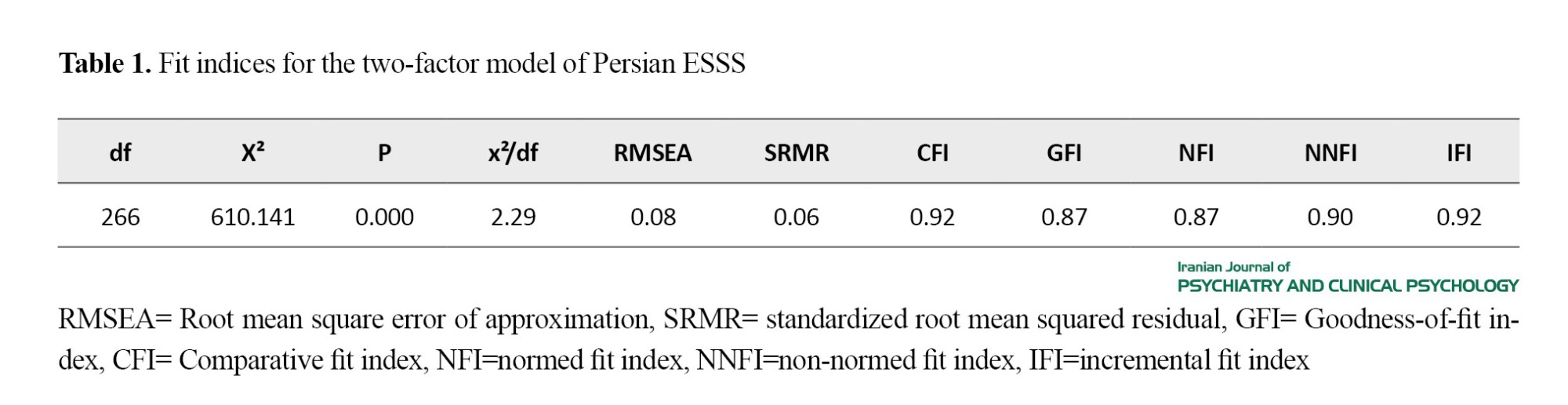

Table 1 presents the values of fit indices for the two-factor structure.

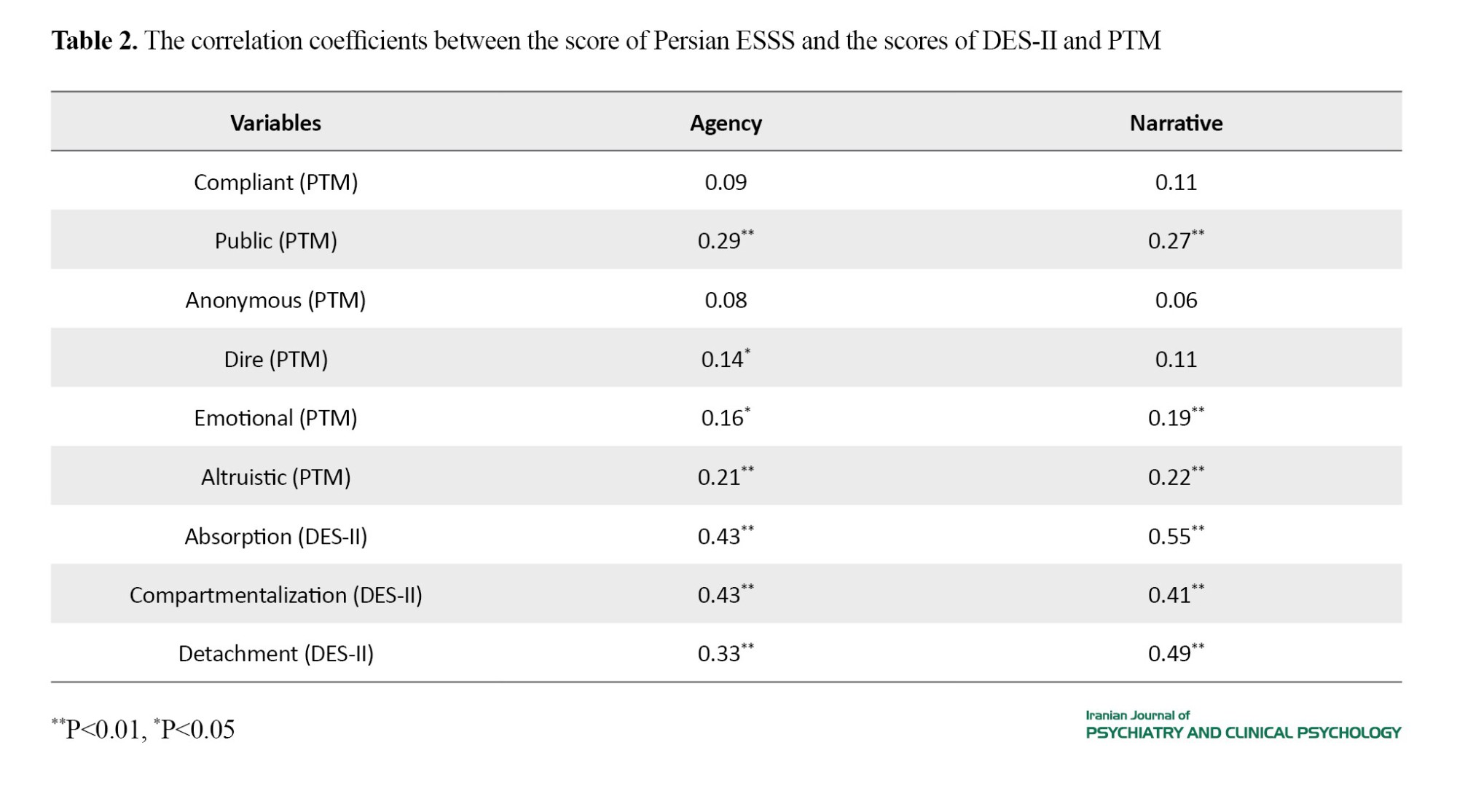

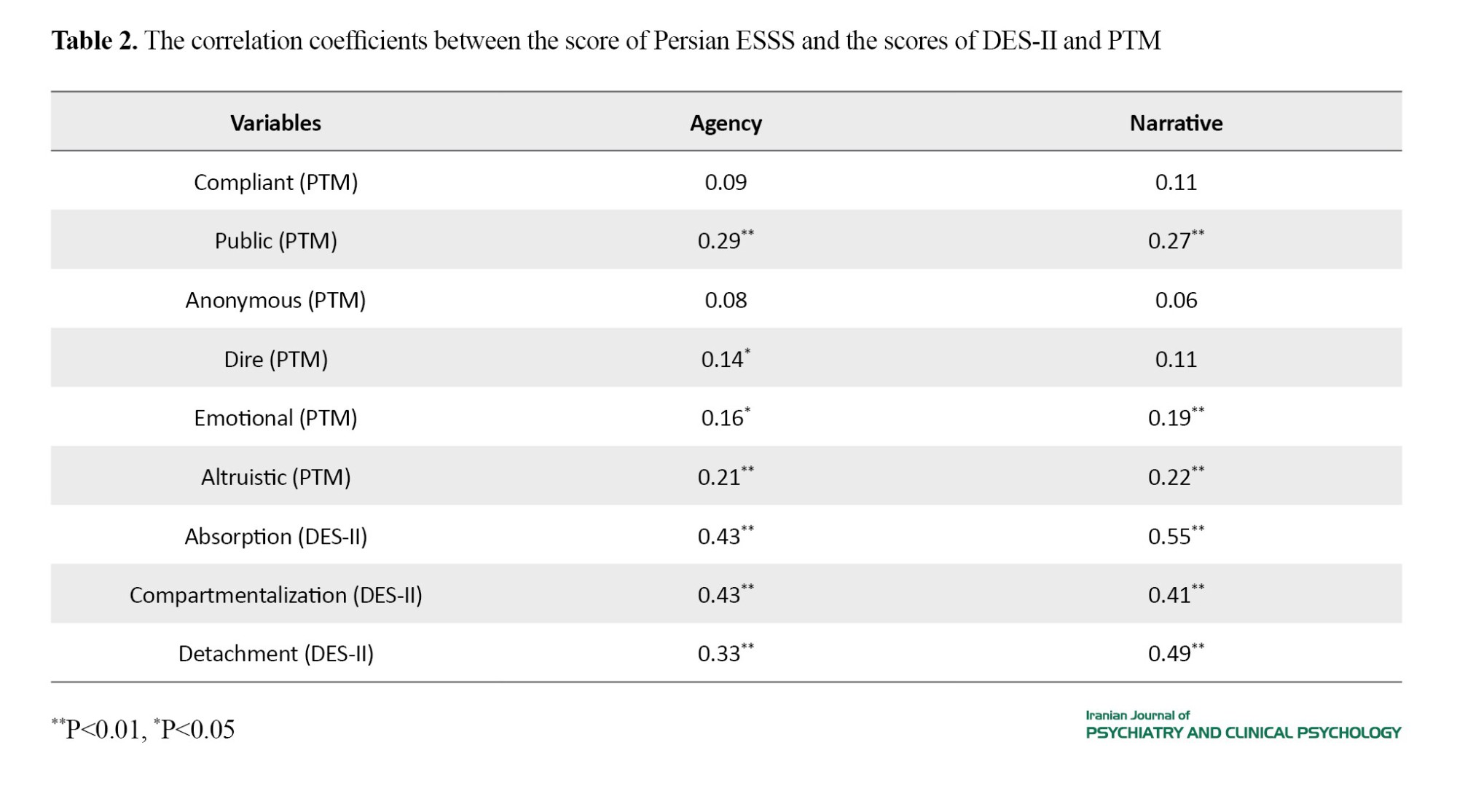

The AVE values for the agency and narrative subscales were 0.45 and 0.52, respectively, indicating a relatively acceptable convergent validity. However, the AVE value for the overall scale was 0.42, indicating low convergent validity. Divergent and concurrent validity were also evaluated by assessing the correlation of the score of ESSS with the scores of DES-II and PTM. Th results are presented in Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha values for narrative and agency subscales were 0.86 and 0.83, respectively and McDonald’s omega values were 0.84 for both subscales, indicating the good internal consistency of the two-factor structure of the Persian ESSS

Conclusion

Based on the results, the two-factor structure of the Persian ESSS demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability. The removal of items related to ownership subscale were due to their lack of consistency with cultural norms of Iran. The results also confirmed the convergent validity of the ESSS. This finding is consistent with the studies identified that dissociation was a key feature of patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorders. In non-clinical samples, this feature also results from a weak sense of agency and the inability to create a meaningful narrative of experiences.

However, divergent validity the Persian ESSS was not fully confirmed. Not all subscales of the PTM had a relationship with the ESSS score. The compliant and anonymous subscales of PTM had no significant relationship with agency and narrative subscales of the Persian ESSS. The lack of correlation between the dire subscale score of the PTM and the narrative domain score of the ESSS suggests that dire behaviors are short-term and not related to stable personality traits. There was a positive correlation between altruistic tendencies and both narrative and agency domains of the ESSS, which is against the previous studies that reported greater impairments in these domains with fewer altruistic behaviors.

Overall, it can be concluded that the Persian ESSS with two domains of narrative and agency has an acceptable validity and reliability for Iranian samples. However, further exploratory factor analysis seems necessary to achieve the optimal validity.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from Tarbiat Modares University (code: IR.MODARES.REC.1401.163). All ethical principles were considered in this study. The participants were informed about the study objectives. They were also assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public commercial or not-forprofit sectors.

Authors contributions

investigation, data collection and writing the initial draft: Nikoo Zargarani; Review and editing: Parviz Azadfallah; Statistical analysis: Hojatullah Farahani.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the people participated in this study for their cooperation.

Most of recent studies in psychology, philosophy and neuroscience have focused on assessing brain representations of the sense of self [1، 2]. Despite numerous objective and experimental studies on the relationship between body and sense of self, its development as a phenomenological whole has received less attention [3]. Consequently, recent studies have concentrated on the concept of embodiment. The embodied sense of self (ESS) refers to subjective feelings grounded within our own body and sensorimotor system [4], evaluated based on multimodal sensory integration [5] or the congruence of motor predictions and actual feedbacks [6].

Theories propose two components of the sense of self including minimal and narrative self. The minimal self is the pre-reflective [7] and pre-linguistic [8] self-awareness of other entities through the body [9-12]. However, the minimal self is insufficient for forming complete representations of the self [2]. The narrative self is a concept developed to address this gap. This social narrative construct, as a form of first-person ownership, relies on the minimal self and is shaped and reconfigured through our efforts to make sense of our evolving experiences [13]. Minimal self is recognized based on sense of self-ownership and self-agency while narrative self is defined by continuity and conformity. The development of ESS is always accompanied by errors that lead to outcomes such as the breakdown of self-other boundaries, dissociation and somatization [14]. These errors not only affect the improvement of psychological disorders in individuals with brain injuries, but also influence their return to normal life [15], potentially increasing the risk of dissociative and psychotic spectrum disorders in the general population.

There are very few tools to measure various dimensions of embodiment. The existing tools often concentrate on a specific group or examine the outcomes of embodiment as an indicator of well-being [19]. The embodied sense of self scale (ESSS) with 25 items and three domains (agency, ownership and narrative), is a tool designed to evaluate the relationship between the body and the sense of self, [2]. The ownership refers to the sense of ownership over the body, possessions, and the self. Its impairment is manifested by depersonalization [16]. Impaired sense of agency is manifested by an inability to manipulate the body, use tools, or perform desired actions, which is observed in the general population and those with schizotypal personality traits, in addition to individuals with schizophrenia [2، 17]. Narrative domain evaluates the temporal continuity and unique nature of the self, which can be seen through bodily movements and actions. Although impaired narrative domain is mainly present in individuals with schizophrenia, it is most seen in those with schizotypal personality traits [2]. The validity assessments of the Italian version of the ESSS revealed that the three-factor model does not adequately fit the Italian samples. Exploratory factor analysis results suggested an alternative model with three factors: self-recognition, self- consistence, and self-awareness [18].

The ESSS is the only tool that focuses on the organization of bodily self in the general population, improvement of the consequences of brain injuries, and prevention of psychotic and dissociative disorders. Moreover, since embodied subjectivity is formed interpersonally, response to others and the cultural context encompass factors such as gender, ethnicity, sex and disability, which always influence bodily perspective and our definition of the self [13]. This has caused different cultures to look at ESS from different perspectives. The present study aims to validate and assess the reliability of the Persian version of ESSS for the Iranian samples.

Methods

This is a psychometrics study. Participants were 215 Iranian people aged 20-65 years (160 females and 55 males, mean age: 34.33±10.81 years), who were selected from those members in social networks (Telegram and WhatsApp). The sample size was determined according to Bentley and Chou’s study [17]. Given that the ESSS has 25 items, the required sample size ranges from 125 to 375. To compensate for sample dropouts, sampling continued until reaching the necessary number of participants. The sampling was done online using a convenience sampling method. The people with age ≥19 years and those who declared consent to participate in the study were included. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate, failure to respond to at least one question, or having a specific response pattern.

The Persian version of the ESSS was prepared after translation and back-translation, and verification of conceptual equivalency of the scales [18]. The original scale was translated into Persian by a PhD student in psychology and an English language specialist. After modification, the translated versions were cross-checked with the English version by a member of the faculty of psychology who was expert in both culture and English. Subsequently, the draft was re-translated into English by an English translator, and the primary author compared it with the main version to confirm consistency. Finally, the Persian version of the ESSS as well as the dissociative experiences scale II (DES-II) and prosocial tendencies measure (PTM) were sent to participants online to complete

Construct validity was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), while convergent validity was evaluated using the average variance extracted (AVE). Pearson correlation test was employed to examine concurrent and divergent validity. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficient. Data analysis was conducted in SPSS sofware, version 27 and R version 4.3.2 Lavaan package

Results

Results of CFA showed that the three-factor solution of the Persian ESSS had an acceptable construct validity but not optimum fit. The items for the ownership subscale were deleted because their factor loads were lower than the acceptable value of 0.4. The final CFA model is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1 presents the values of fit indices for the two-factor structure.

The AVE values for the agency and narrative subscales were 0.45 and 0.52, respectively, indicating a relatively acceptable convergent validity. However, the AVE value for the overall scale was 0.42, indicating low convergent validity. Divergent and concurrent validity were also evaluated by assessing the correlation of the score of ESSS with the scores of DES-II and PTM. Th results are presented in Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha values for narrative and agency subscales were 0.86 and 0.83, respectively and McDonald’s omega values were 0.84 for both subscales, indicating the good internal consistency of the two-factor structure of the Persian ESSS

Conclusion

Based on the results, the two-factor structure of the Persian ESSS demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability. The removal of items related to ownership subscale were due to their lack of consistency with cultural norms of Iran. The results also confirmed the convergent validity of the ESSS. This finding is consistent with the studies identified that dissociation was a key feature of patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorders. In non-clinical samples, this feature also results from a weak sense of agency and the inability to create a meaningful narrative of experiences.

However, divergent validity the Persian ESSS was not fully confirmed. Not all subscales of the PTM had a relationship with the ESSS score. The compliant and anonymous subscales of PTM had no significant relationship with agency and narrative subscales of the Persian ESSS. The lack of correlation between the dire subscale score of the PTM and the narrative domain score of the ESSS suggests that dire behaviors are short-term and not related to stable personality traits. There was a positive correlation between altruistic tendencies and both narrative and agency domains of the ESSS, which is against the previous studies that reported greater impairments in these domains with fewer altruistic behaviors.

Overall, it can be concluded that the Persian ESSS with two domains of narrative and agency has an acceptable validity and reliability for Iranian samples. However, further exploratory factor analysis seems necessary to achieve the optimal validity.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from Tarbiat Modares University (code: IR.MODARES.REC.1401.163). All ethical principles were considered in this study. The participants were informed about the study objectives. They were also assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public commercial or not-forprofit sectors.

Authors contributions

investigation, data collection and writing the initial draft: Nikoo Zargarani; Review and editing: Parviz Azadfallah; Statistical analysis: Hojatullah Farahani.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the people participated in this study for their cooperation.

References

- Zahavi D. We in me or me in we? Collective intentionality and selfhood. Journal of Social Ontology. 2021; 7(1):1-20. [Link]

- Asai T, Kanayama N, Imaizumi S, Koyama S, Kaganoi S. Development of embodied sense of self scale (ESSS): Exploring everyday experiences induced by anomalous self-representation. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016; 7:1005. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01005] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Haggard P, Chambon V. Sense of agency. Current Biology. 2012; 22(10):R390-2. [DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.040] [PMID]

- Weiss C, Tsakiris M, Haggard P, Schütz-Bosbach S. Agency in the sensorimotor system and its relation to explicit action awareness. Neuropsychologia. 2014; 52:82-92. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.09.034] [PMID]

- Kilteni K, Maselli A, Kording KP, Slater M. Over my fake body: Body ownership illusions for studying the multisensory basis of own-body perception. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2015; 9:141. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00141] [PMID] [PMCID]

- David N, Newen A, Vogeley K. The "sense of agency" and its underlying cognitive and neural mechanisms. Consciousness and Cognition. 2008; 17(2):523-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.004] [PMID]

- Gallagher S. A pattern theory of self. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013; 7:443. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00443]

- Gallagher S, Zahavi D. The phenomenological mind. London: Routledge; 2012. [DOI:10.4324/9780203126752]

- Sletvold J. Neuroscience and the embodiment of psychoanalysis—with an appreciation of Damasio’s contribution. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 2019; 39(8):545-56. [DOI:10.1080/07351690.2019.1671067]

- Damasio A. Self comes to mind: Constructing the conscious brain. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group; 2012. [Link]

- Husserl E. Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy. Berlin: Springer; 1989. [Link]

- Merleau-Ponty M. The essential writings of Merleau-Ponty. New York : Harcourt, Brace & World; 1969. [Link]

- Mackenzie C. Embodied agents, narrative selves. Philosophical explorations. 2014; 17(2):154-71. [DOI:10.1080/13869795.2014.886363]

- O’callaghan SM. Precarious bodies. A psychoanalytic and literary perspective on anomalous embodiment. Lacunae. 2015; (10):1-12. [Link]

- Sivertsen M, Normann B. Embodiment and self in reorientation to everyday life following severe traumatic brain injury. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2015; 31(3):153-9. [DOI:10.3109/09593985.2014.986350] [PMID]

- Putnam, F.W., Dissociation in children and adolescents: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford press; 1997. [Link]

- Walker EF. Developmentally moderated expressions of the neuropathology underlying schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1994; 20(3):453-80. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/20.3.453] [PMID]

- Patti A, Santarelli G, Baccaredda Boy O, Fascina I, Altomare AI, Ballerini A, et al. Psychometric properties of the italian version of the embodied sense-of-self scale. Brain Sciences. 2022; 13(1):34. [DOI:10.3390/brainsci13010034] [PMID]

- Piran N, Teall TL, Counsell A. The experience of embodiment scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image. 2020; 34:117-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.05.007] [PMID]

- Bentler PM, Chou CP. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research. 1987; 16(1):78-117. [DOI:10.1177/0049124187016001004]

- Gjersing L, Caplehorn JR, Clausen T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: Language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMc Medical Research Methodology. 2010; 10:13. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2288-10-13] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. Bernstein and Putnam. 1986; 174(12):727-35. [DOI:10.1037/e609912012-081]

- Zingrone NL, Alvarado CS. The Dissociative experiences scale-ii: descriptive statistics, factor analysis, and frequency of experiences. Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 2001; 21(2):145-57. [DOI:10.2190/K48D-XAW3-B2KC-UBB7]

- Ghaffarinejad A, Sattari N, Raaii F, Arjmand S. Validity and reliability of a Persian version of the dissociative experiences scale II (DES-II) on Iranian patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and mood disorders. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2020; 21(3):293-304. [DOI:10.1080/15299732.2019.1678209] [PMID]

- Carlo G, Randall BA. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002; 31:31-44. [DOI:10.1023/A:1014033032440]

- Azimpour A. Neasi A, Shehni-Yailagh M, Arshadi N. Validation of “prosocial tendencies measure” in Iranian university students. Journal of Life Science and Biomedicine. 2012. 2(2):34-42. [Link]

- Matsunaga M. How to factor-analyze your data right: Do’s, don’ts, and how-to’s. International Journal of Psychological Research. 2010; 3(1):97-110. [DOI:10.21500/20112084.854]

- Flora DB, Labrish C, Chalmers RP. Old and new ideas for data screening and assumption testing for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012; 3:55. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00055] [PMID]

- Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research. 2006; 99(6):323-38. [DOI:10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Link]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research. 1992; 21(2):230-58. [DOI:10.1177/0049124192021002005]

- Steiger JH. A note on multiple sample extensions of the RMSEA fit index. Structural Equation Modeling. 1998; 5:411-9. [DOI:10.1080/10705519809540115]

- Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, Paxton P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research. 2008; 36(4):462-94. [DOI:10.1177/0049124108314720] [PMID]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996; 1(2):130-49. [DOI:10.1037//1082-989X.1.2.130]

- Sun J. Assessing goodness of fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2005; 37(4):240-56. [DOI:10.1080/07481756.2005.11909764]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Psychology Press; 2013. [DOI:10.4324/9780203774762]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. Paper presented in: ECRM2008-Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methods. 19 June 2008; London, United Kingdom. [Link]

- Bentler PM. On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007; 42(5):825-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024]

- Kline RB. Promise and pitfalls of structural equation modeling in gifted research. In: Thompson B, Subotnik RF, editors. Methodologies for conducting research on giftedness. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2010. [DOI:10.1037/12079-007]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981; 18(3):382-8. [DOI:10.2307/3150980]

- Henseler J. Partial least squares path modeling. In: Leeflang PSH, Wieringa JE, Bijmolt THA, Pauwels KH, ediotors. Advanced methods for modeling markets. Berlin: Springer; 2017. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-53469-5_12]

- Douglas M. Natural symbols. London: Routledge; 2002. [DOI:10.4324/9780203036051]

- Bendelow GA, Williams SJ. The lived body: Sociological themes, embodied issues. London: Routledge; 2002. [DOI:10.4324/9780203025680]

- Saroglou V, Cohen AB. Psychology of culture and religion: Introduction to the JCCP special issue. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011; 42(8):1309-19. [DOI:10.1177/0022022111412254]

- Chebel M. Le corps en Islam. Puf; 2004.

- Mahmood S. Religious difference in a secular age: A minority report. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2015. [Link]

- Mahmood S. The politics of piety: The Islamic revival and the feminist subject. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2012. [DOI:10.1515/9781400839919]

- Shaner DE. The bodymind experience in Japanese Buddhism: A phenomenological study of Kūkai and Dōgen. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1985. [Link]

- Gold JC, Duckworth DS, Teiser S. Readings of śāntideva›s guide to bodhisattva practice. New York: Columbia University Press; 2019. [DOI:10.7312/gold19266]

- Goodboy AK, Martin MM. Omega over alpha for reliability estimation of unidimensional communication measures. Annals of the International Communication Association. 2020; 44(4):422-39. [DOI:10.1080/23808985.2020.1846135]

- Asai T, Mao Z, Sugimori E, Tanno Y. Rubber hand illusion, empathy, and schizotypal experiences in terms of self-other representations. Consciousness and Cognition. 2011; 20(4):1744-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.concog.2011.02.005] [PMID]

- Asai T. Self is "other", other is "self": Poor self-other discriminability explains schizotypal twisted agency judgment. Psychiatry Research. 2016; 246:593-600. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.082] [PMID]

- Brazil KJ, Volk AA, Dane AV. Is empathy linked to prosocial and antisocial traits and behavior? It depends on the form of empathy. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2023; 55(1):75. [DOI:10.1037/cbs0000330]

- Lockwood PL, Seara-Cardoso A, Viding E. Emotion regulation moderates the association between empathy and prosocial behavior. Plos One. 2014; 9(5):e96555. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0096555] [PMID]

- Knight GP, Carlo G, Mahrer NE, Davis AN. The socialization of culturally related values and prosocial tendencies among Mexican-American adolescents. Child Development. 2016; 87(6):1758-71. [DOI:10.1111/cdev.12634] [PMID]

- Henry JD, Rendell PG, Green MJ, McDonald S, O'Donnell M. Emotion regulation in schizophrenia: Affective, social, and clinical correlates of suppression and reappraisal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008; 117(2):473-8. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.473] [PMID]

- Richaud, M.C., B. Mesurado, and A. Kohan Cortada. Analysis of dimensions of prosocial behavior in Argentine’s children and youngers. Paper presented in: SRCD. Biennial Meeting. 2 April 2011; Montreal, Canada. [Link]

- Calderón-Tena CO, Knight GP, Carlo G. The socialization of prosocial behavioral tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: The role of familism values. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011; 17(1):98-106. [DOI:10.1037/a0021825] [PMID]

- Yan C, Cao Y, Zhang Y, Song LL, Cheung EF, Chan RC. Trait and state positive emotional experience in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Plos One. 2012; 7(7):e40672. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0040672] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N. Meta-analyses of age and sex differences in children’s and adolescents’ prosocial behavior. Handbook of Child Psychology. 1998; 3:1-29. [Link]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2023/12/2 | Accepted: 2024/07/14 | Published: 2024/08/19

Received: 2023/12/2 | Accepted: 2024/07/14 | Published: 2024/08/19

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |