Tue, Jul 1, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 29, Issue 4 (Winter 2024)

IJPCP 2024, 29(4): 514-531 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abbes W, Kerkeni A, Emna E. Prevalence of Childhood Sexual Abuse Among Tunisian Psychiatric Outpatients and its Associated Factors. IJPCP 2024; 29 (4) :514-531

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3972-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3972-en.html

1- Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital of Gabes, Gabes, Tunisia.

2- Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital of Gabes, Gabes, Tunisia. ,ali.karknii@gmail.com

3- Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Gabes, Gabes, Tunisia.

2- Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital of Gabes, Gabes, Tunisia. ,

3- Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Gabes, Gabes, Tunisia.

Full-Text [PDF 4578 kb]

(513 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1691 Views)

Full-Text: (419 Views)

Introduction

childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has been frequently reported by patients who visit psychiatric centers and seems to affect the development of psychiatric disorders [1]. The study of CSA in psychiatric patients is particularly interesting because it can improve the quality of care provided to them [2]. The CSA in psychiatric patients is significantly associated with the prevalence of anxiety, depression, addiction, and suicidal thoughts [3–6]. The prevalence of CSA in psychiatric patients varies in different countries; it is 12.5% in China [7], 23% in South Korea [8], and 24.8% in Ireland [9]. Their association is evident with an earlier onset of psychiatric symptoms, gradual deterioration of psychiatric disorders, increased suicide risk, and reduced quality of life [10]. Studies in Tunisia on the CSA in psychiatric patients are limited. In a comparative study on a group of Tunisian patients with bipolar disorder and controls, CSA was significantly higher in patients with bipolar disorder [11]. The CSA is also associated with the presence of psychotic features during decompensation. In another Tunisian study, 12.9% of child victims of sexual abuse had developed chronic mental illnesses (psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, conduct disorders) [12].

One of the difficulties in investigating the CSA rate is the diversity of the used terms. The difference in the criteria for CSA creates a potential for overestimating or underestimating the prevalence of CSA in psychiatric patients as well as the associated factors. The 2006 World Health Organization report called for developing a standard definition for child maltreatment and standard operational definitions for its identification [13]. In this study, we adopt the definition provided by Mathews and Collin-Vézina [14]: “Unwanted sexual contact (genital touching and fondling to penetration) while the victim is a child by legal definition and the perpetrator is in a position of relative power vis a vis the victim (e.g. parent, adult, babysitter, guardian, older child, etc.).” Barth et al. [15] have emphasized the importance of standardizing a CSA assessment method using validated psychometric tools.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Tunisia to estimate the prevalence of CSA in psychiatric outpatients and to find the associated sociodemographic and clinical factors. We hypothesized that psychiatric outpatients with CSA have a higher functional impairment, comorbidities, admissions rate to psychiatric centers, and suicidal thoughts than those without a history of CSA.

Methods

Study area and sample size

This study was conducted from January 1 to July 30, 2021. Participants were recruited from patients referred to the consultant clinic of the Department of Psychiatry, Hospital of University of Gabes. The clinic provides outpatient services to adults with psychiatric disorders. The sample size was calculated using the following formula: N=(P×Q×4)/0.02², where P is the prevalence of CSA among the Tunisian general population set at 0.1 % according to El Mhamdi et al.’s study in 2016 [16], and Q=1- P. The minimum number of samples was estimated at 111, considering a precision of 2%, a confidence interval of 95%, and a sample dropout rate of 10%.

Participants

We included the patients who met the following criteria: Age ≥18 years, a diagnosed psychiatric disorder according to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders – fifth edition (DSM-5) [17], a history of psychiatric disorders that were clinically stable for at least three months, and declaring a written consent. We excluded patients with intellectual disabilities or major cognitive impairments that hindered the completion of the questionnaires. In the end, 133 eligible psychiatric outpatients participated in our study. One author interviewed the participants immediately after the regular psychiatric consultation to confirm the results. The average duration of the interview was 30 minutes.

Measures

Socio-demographic and clinical forms

We used a pre-defined form to collect socio-demographic characteristics. Clinical data were extracted either from the participants’ medical records or from their psychiatrists.

Childhood trauma questionnaire short form (CTQ-SF)

The CTQ-SF is a self-administered questionnaire with 28 items rated on a five-point Likert scale. It is used to measure the severity of trauma during childhood. It has five sub-scales measuring different dimensions of child abuse: Physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect [18]. Participants with a score ≥8 were considered to have a history of CSA [19]. This questionnaire was translated from English into Arabic and back translated into English for linguistic adaptation. The final version was considered after comparing the two versions. In the current study, the Arabic version of the CTQ-SF had solid convergent validity and acceptable reliability for the sexual abuse subscale (Cronbach’s α=0.755).

The suicide behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R)

The SBQ-R is a self-administered questionnaire developed by Osman et al. [20] inadequate attention has been given to the development or validation of measures of past suicidal behavior. The present study examined the reliability and validity of a brief self-report measure of past suicidal behavior, the suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R to study suicide behaviors. This scale has been used for general adult populations in different countries due to acceptable reliability, brevity, ease of use, and stability [21, 22]. This instrument has four items. The first item taps into lifetime suicide ideation and suicide attempts. The second item assesses the frequency of suicide ideation over the past 12 months. The third item assesses the threat of suicide attempts. The final item assesses the risk of committing suicide in the future. The SBQ-R was translated into Arabic according to the recommendation of Wild et al. [23]. For its internal consistency, Cronbach’s α was 0.84, which was acceptable. In the present study, option 2 for item 1 was used to indicate the risk of suicide ideation, and options 4a and 4b for item 1 were used to indicate previous suicide attempts [24].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was done in the statistical package for social sciences software (SPSS) version 20. Quantitative variables were described using means and Mean±SD. For these variables, we checked the normality of data distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test. The qualitative variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies (percentages). Data were analyzed using the chi-square test, Fischer’s exact test, and independent t-test. A logistic regression analysis was applied to determine the best linear combination of factors associated with CSA. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

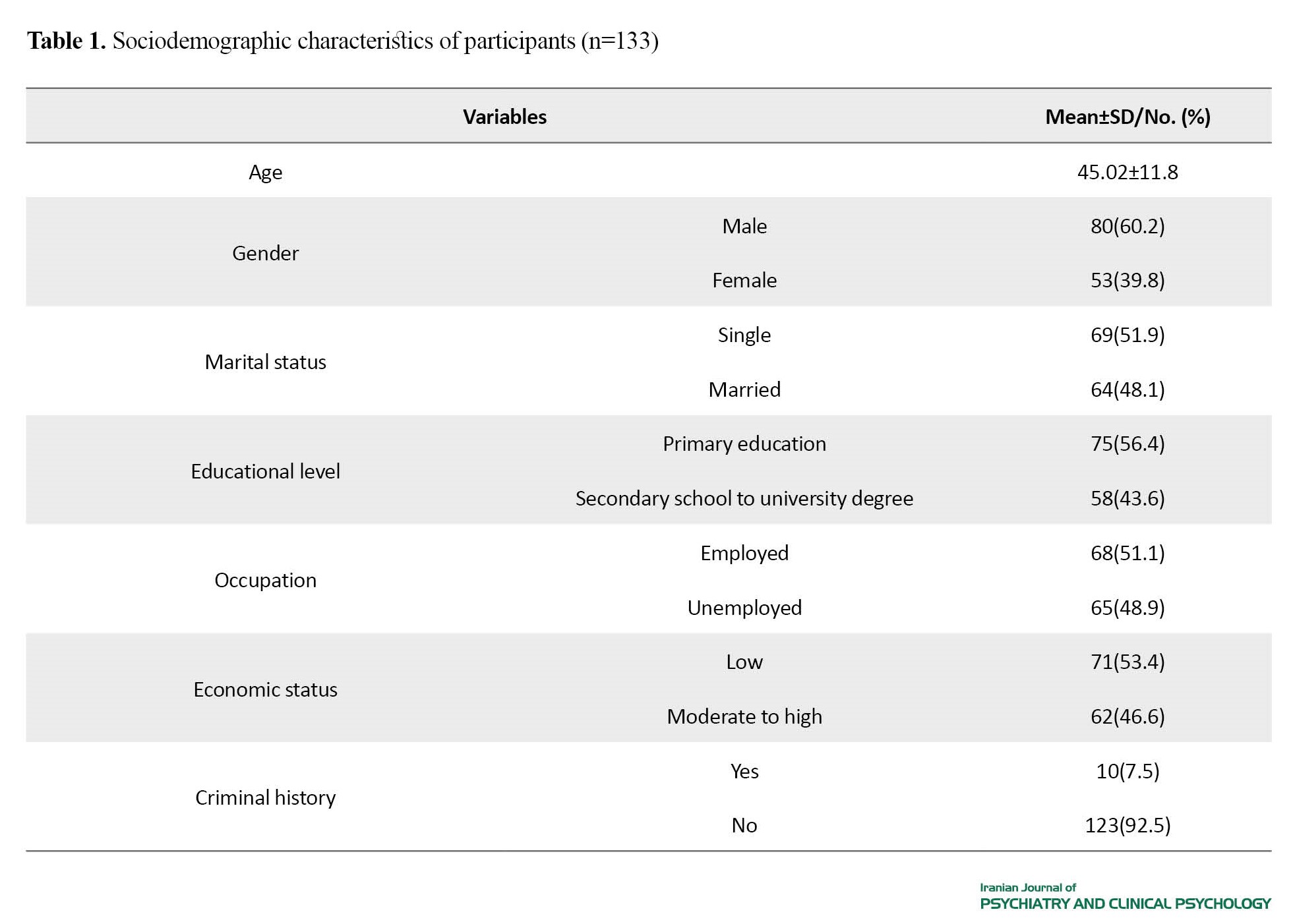

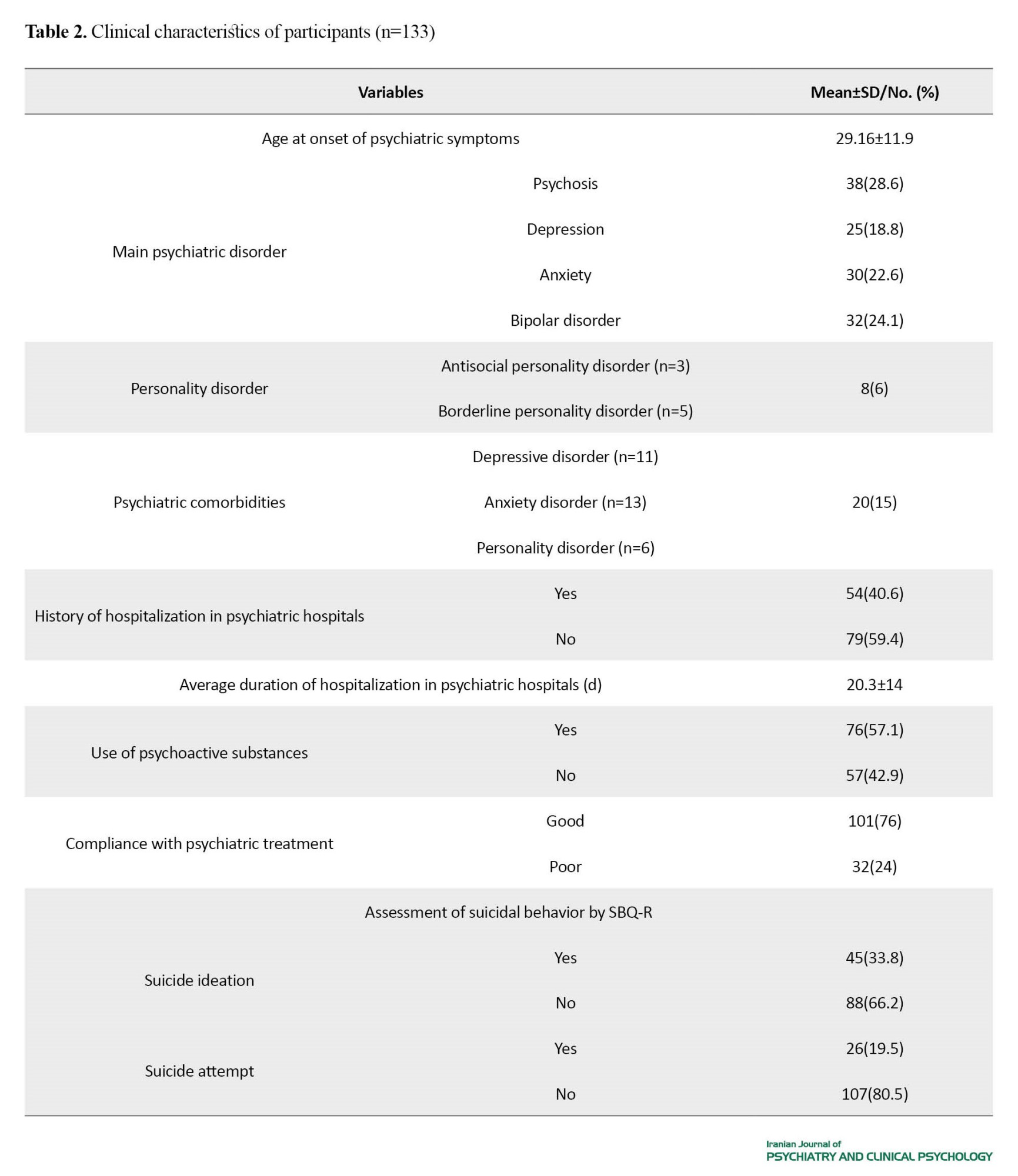

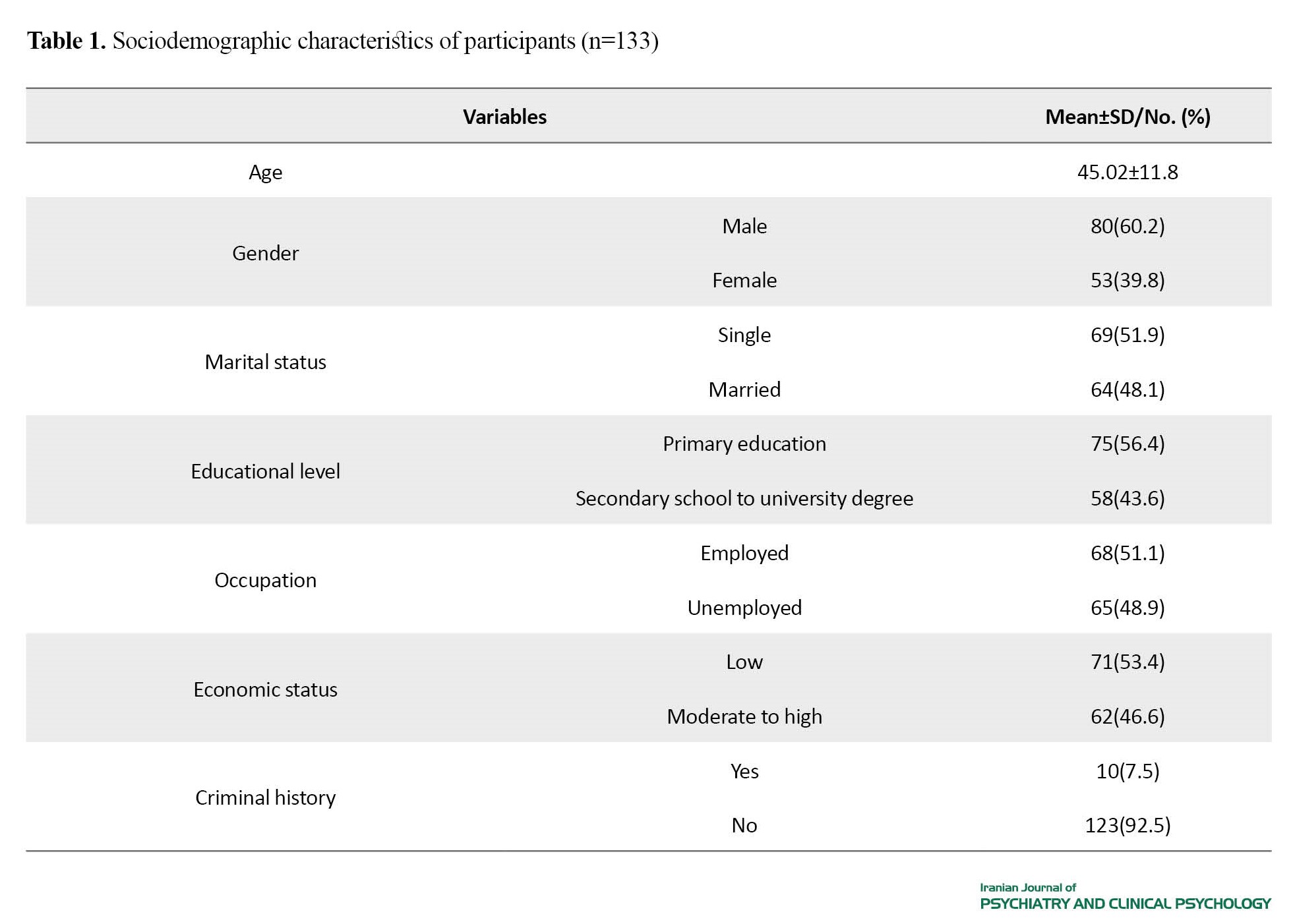

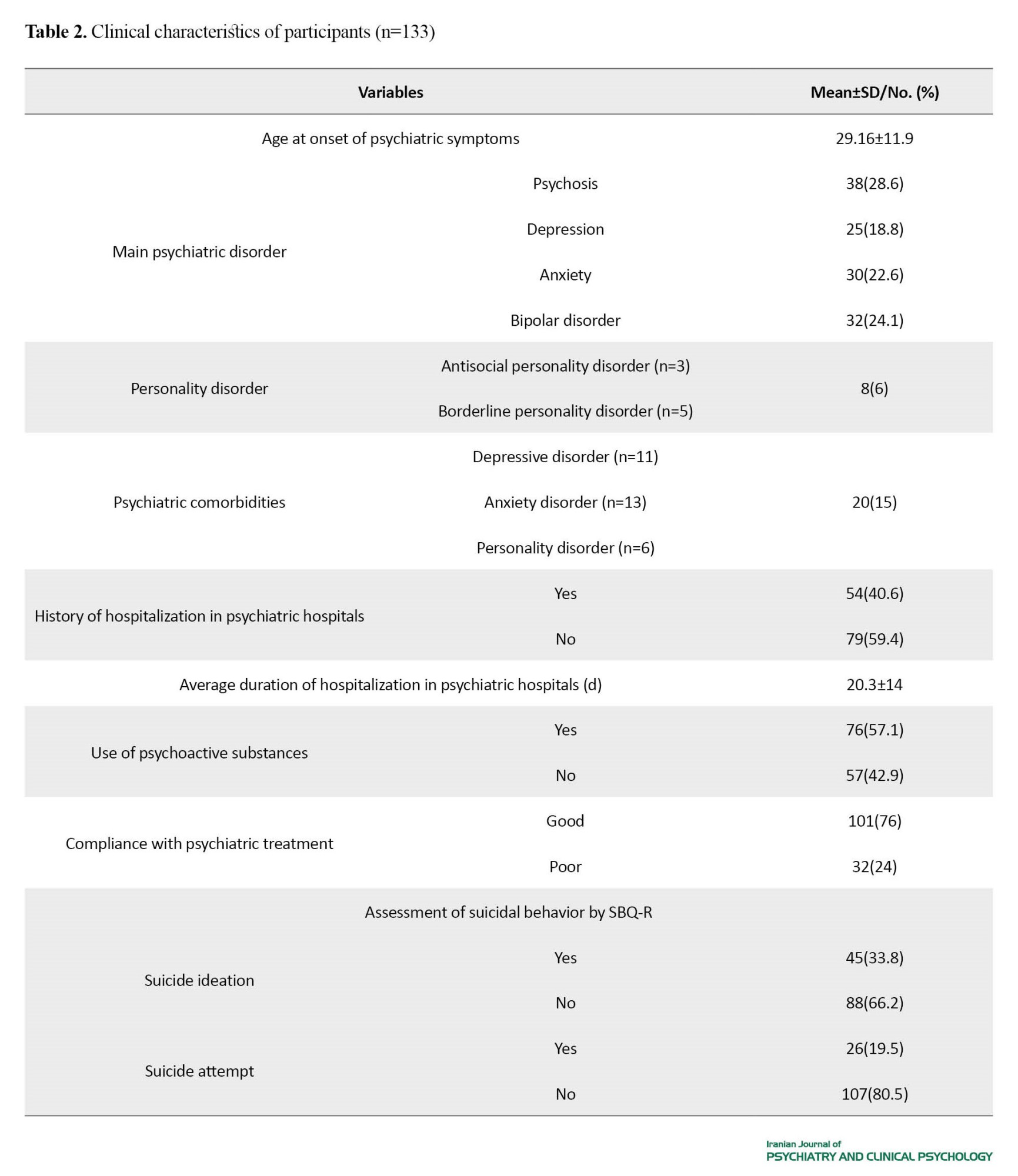

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 1 and 2.

The mean age of the participants was 45.02±11.8 years, with a sex ratio (M: F) of 1:5. The primary diagnosis was psychosis (28.6%). The SBQ-R score showed that 33.8% of participants had a history of suicide ideation, and 19.5% had a history of suicide attempt. The mean score of the sexual abuse subscale in the CTQ-SF was 5.93±2.3, ranging from 5 to 25. We found that 9.8% of participants had scores ≥8 in this subscale (n=13), corresponding to the prevalence of CSA.

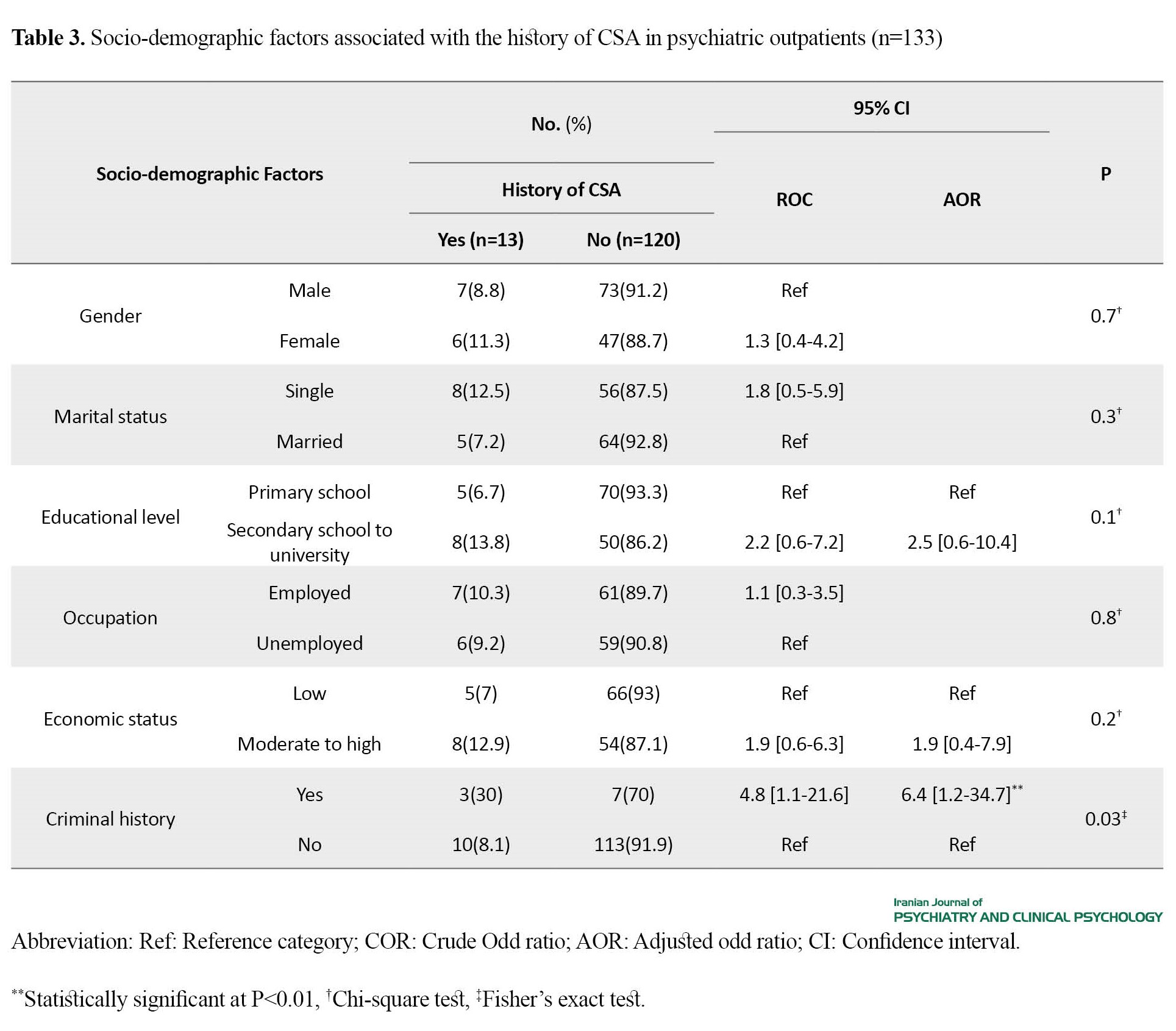

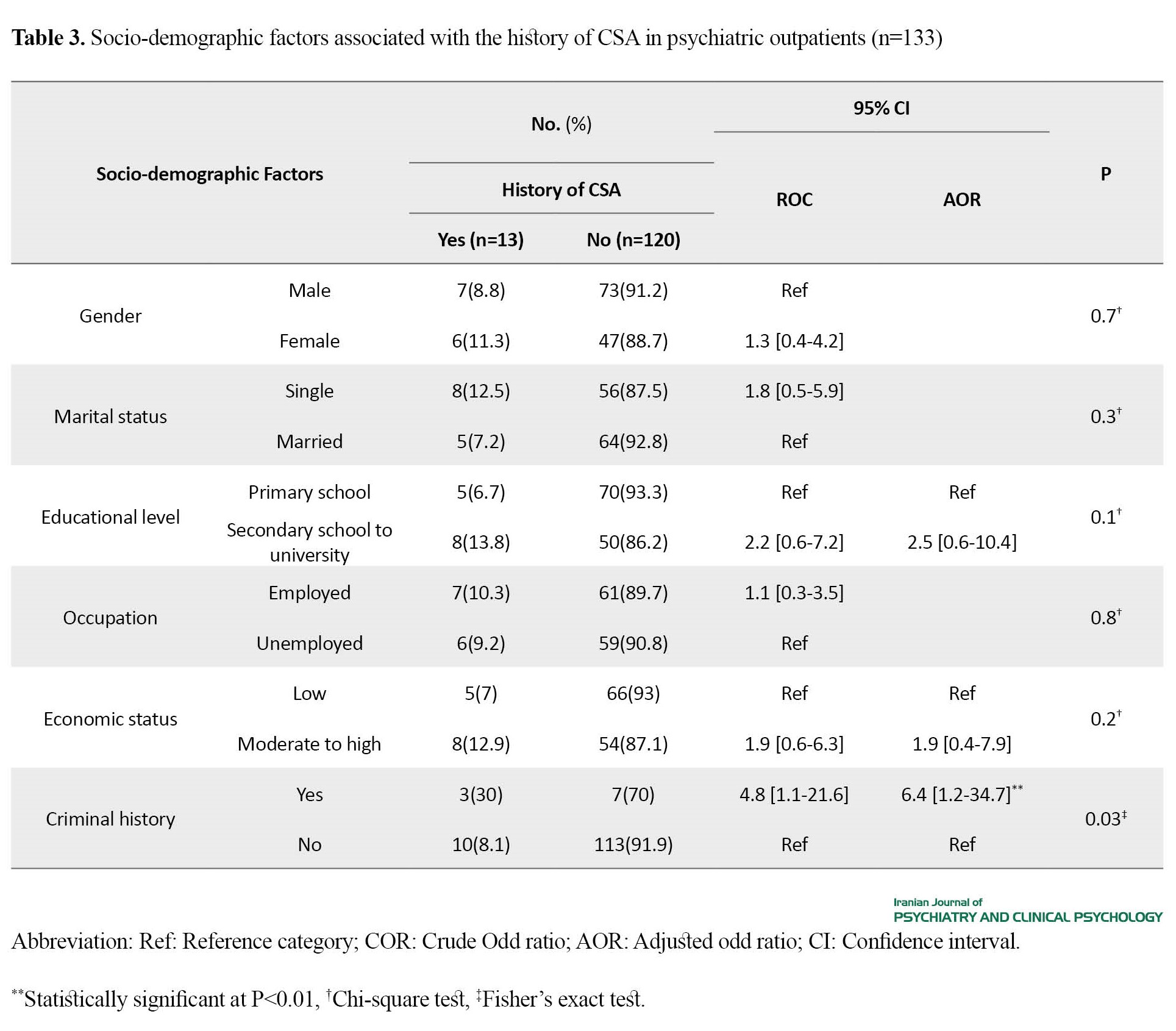

The socio-demographic factors associated with the history of CSA are presented in Table 3.

We did not find a significant association between the history of CSA and the factors of age, gender, marital status, educational level, occupation, and economic status. The multivariate analysis showed that the history of CSA in psychiatric outpatients increased the risk of having a criminal record by 6.4 (AOR=6.4; 95% CI, 1.2%, 34.7%).

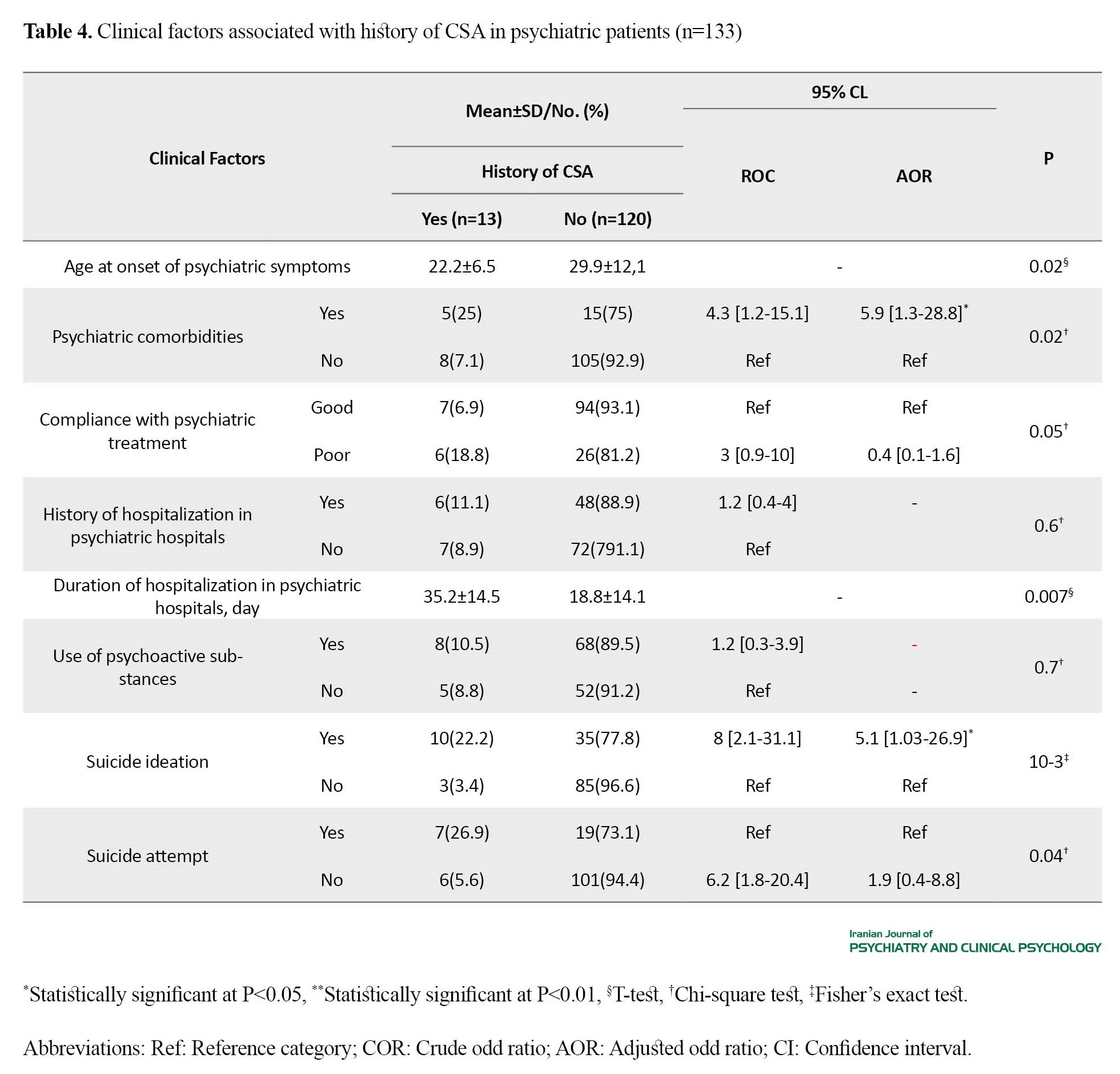

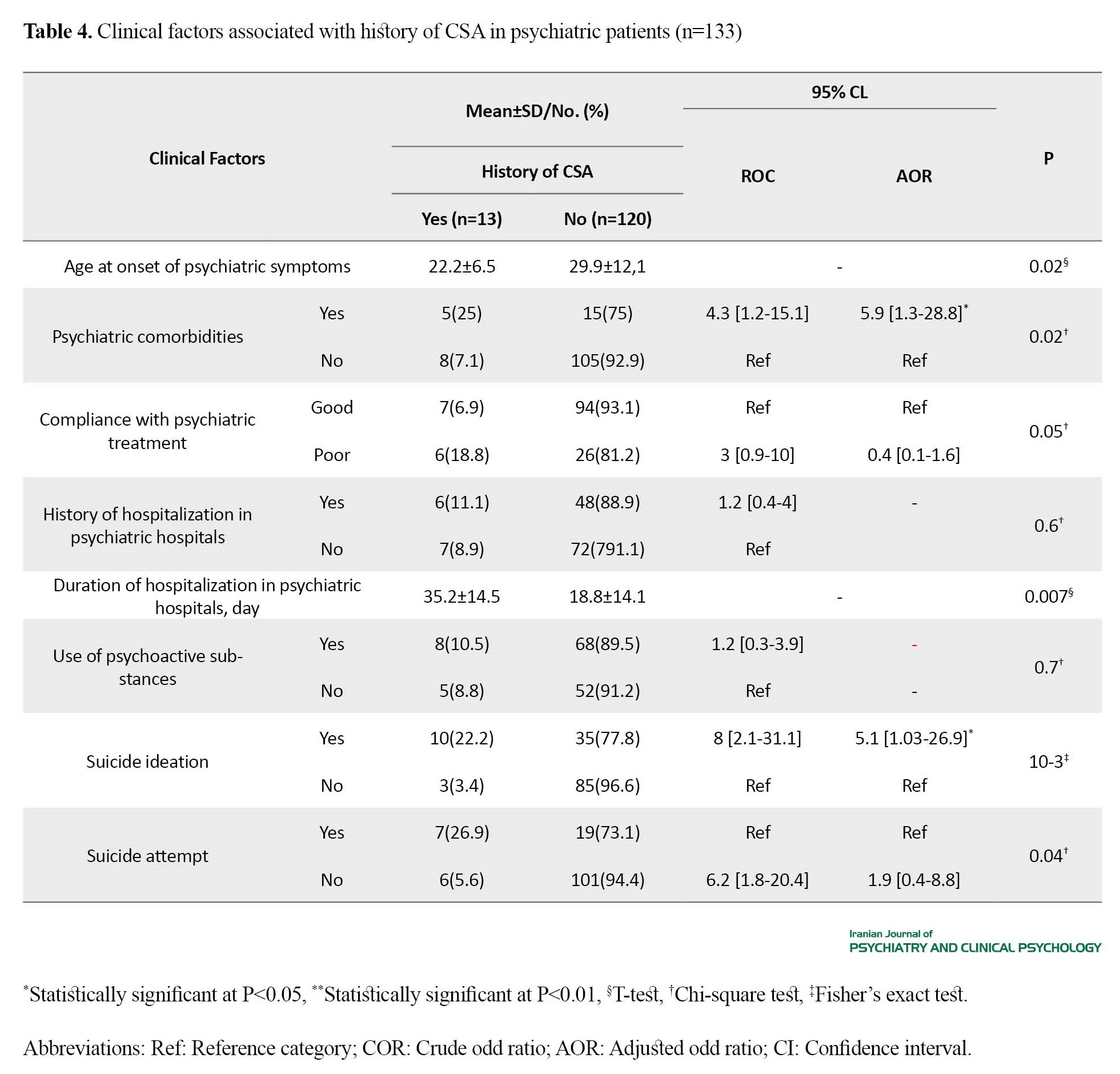

The clinical factors associated with the history of CSA are summarised in Table 4.

The CSA was significantly associated with a younger age at onset of psychiatric symptoms, psychiatric comorbidities, and a longer duration of psychiatric hospital stay. The history of suicide ideation and psychiatric comorbidities increased the likelihood of a history of CSA by 5.1 (AOR=5.1; 95% CI, 1.03%, 26.9%) and 5.9 (AOR=5.9; 95% CI, 1.3%, 28.8%), respectively.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that only 9.8% of outpatients had a history of CSA, which was significantly lower than the rates reported in many similar studies. This rate was 23% in a study conducted among psychiatric patients in South Korea [8], 20.7% in the U.S.[25], and 35.3% in Canada [26]. A possible explanation for this result is that, in Tunisia, due to socio-cultural factors, it is not expected to talk about sexual abuse in childhood, even to parents. Thus, the majority might not feel comfortable reporting their CSA. Therefore, the anonymous self-administered CTQ-SF can be more appropriate to estimate the prevalence of CSA in Tunisian patients. Another possible explanation is the validity of the used instrument. We examined the presence of CSA in our patients using the Arabic version of CTQ-SF. This questionnaire is the most widely used scale for measuring childhood trauma due to the ease of use and the stability of its psychometric characteristics in different cultures [27]. Studies have indicated the importance of cross-cultural adaptation for the CTQ-SF in terms of factor structure during its translation and the importance of defining positive thresholds for its sub-scales, adapted to the study population [7, 28].

We did not find a significant association between CSA history and gender, which is against the results of a similar study conducted in the UK [29]. This discrepancy can be due to the low ratio of women to men in our study (1:5) or the reluctance of men to disclose the CSA [30]. We did not find a significant association of CSA with educational level, marital status, economic status, or occupation, either. Our results showed that the patients with CSA had a higher criminal history. This result is consistent with the results of a study that reported that CSA is an independent risk factor for later antisocial behaviors [31]. This result can be explained by the fact that individuals who are victims of physical abuse during childhood tend to have aggressive behaviors towards others in adulthood. They grew up with the belief that violence can help them get what they want. The experience of sexual abuse during childhood seems to increase the risk of being a criminal in adulthood by 30%, which evokes the concept of intergenerational transmission of violence [32]. Having antisocial behaviors can be a way of self-protection for the victims of sexual abuse, a way to be independent of others and avoid intimate relationships, which are perceived as a sign of emotional weakness [33].

In the present study, the CSA was significantly associated with a younger age at onset of psychiatric symptoms and the presence of psychiatric comorbidities. This finding is consistent with findings of previous studies, which reported that the experience of childhood maltreatment was associated with subsequent onset of psychiatric disorders, psychiatric disorders’ increased risk of recurrence, resistance to treatment, and a longer treatment period [34]. We found that the CSA in psychiatric outpatients was also significantly associated with a longer duration of hospitalization in psychiatric centers. Similar results have been reported in the literature. Previous studies have reported that patients with a history of CSA were more likely to be hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals; they were 30% more likely to be hospitalized for more than ten days per year than patients without a history of CSA and were 2.5 times more likely to receive high doses of antipsychotics [35–37]. This result can be explained by the increased severity of psychiatric disorders in these patients and the frequency of psychotic episodes during decompensation.

Moreover, our results showed that CSA was significantly associated with suicide ideation, which is in agreement with other studies. This result was explained by the frequency of anxiodepressive disorders (3) due to emotional dysregulation in these patients (5), the mediating role of hopelessness (6), and the increased neurobiological vulnerability, causing the dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex, corpus callosum, and the dysregulation of cortisol secretion [38–40].

The CSA could significantly predict suicidal ideation in psychiatric patients but not their suicide attempts. Evidence from the literature concerning the role of CSA in suicide attempts is varying. Overall, suicide attempts are complicated behaviors affected by several individual, clinical, and environmental factors and should be interpreted based on the results of an overall assessment. In the U.S., results of a study showed that, although depression significantly predicted suicidal ideation, it could not significantly predict suicide attempts, which were associated with anxiety, poor impulse control, and substance abuse [41].

Given the evidence for the high prevalence of CSA among psychiatric outpatients, we recommend clinicians to inquire about CSA in psychiatric patients frequently. Strong evidence suggests that disclosure of CSA during psychotherapy may reduce PTSD symptoms [42]. Cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, and group therapy seem to be effective options for treatment [43–45].

There were some limitations in the present study. There was a lack of detailed information regarding the perpetrators of the CSA in patients, as well as information on their intensity. Also, it was not possible to study the causal links between CSA and various psychiatric diagnoses. Comparative studies using a larger sample size for each psychiatric diagnosis, including a control group, may be more suitable for studying these possible links. The lack of a validated instrument for the Tunisian culture was another limitation. The study's cross-sectional design limited the exploration of the evolutionary aspects of the associations. Longitudinal studies are recommended to better evaluate them.

Conclusion

Our study highlighted the importance of assessing the history of CSA in psychiatric patients. The multiple admissions and longer hospitalizations, the presence of suicidal thoughts, and psychiatric comorbidities can predict CSA. We emphasize the need to systematically evaluate the history of CSA in psychiatric patients to develop appropriate plans for mitigating the adverse effects of CSA on their psychiatric disorders and to ensure early and effective psychosocial care.

Our study highlighted the importance of assessing the history of CSA in psychiatric patients. The multiple admissions and longer hospitalizations, the presence of suicidal thoughts, and psychiatric comorbidities can predict CSA. We emphasize the need to systematically evaluate the history of CSA in psychiatric patients to develop appropriate plans for mitigating the adverse effects of CSA on their psychiatric disorders and to ensure early and effective psychosocial care.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Participants were informed about their right to leave the study at any time and signed a written informed consent form. Ethical approval (Code: 0459/2020) was obtained from the regional Ethics Committee CPP SUD (Committee of Person Protection), and the procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

The authors contributed equally to preparing this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has been frequently reported by patients who visit psychiatric centers and seems to affect the development of psychiatric disorders [1]. The study of CSA in psychiatric patients is particularly interesting because it can improve the quality of care provided to them [2]. The CSA in psychiatric patients is significantly associated with the prevalence of anxiety, depression, addiction, and suicidal thoughts [3–6]. The prevalence of CSA in psychiatric patients varies in different countries; it is 12.5% in China [7], 23% in South Korea [8], and 24.8% in Ireland [9]. Their association is evident with an earlier onset of psychiatric symptoms, gradual deterioration of psychiatric disorders, increased suicide risk, and reduced quality of life [10]. Studies in Tunisia on the CSA in psychiatric patients are limited. In a comparative study on a group of Tunisian patients with bipolar disorder and controls, CSA was significantly higher in patients with bipolar disorder [11]. The CSA is also associated with the presence of psychotic features during decompensation. In another Tunisian study, 12.9% of child victims of sexual abuse had developed chronic mental illnesses (psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, conduct disorders) [12].

One of the difficulties in investigating the CSA rate is the diversity of the used terms. The difference in the criteria for CSA creates a potential for overestimating or underestimating the prevalence of CSA in psychiatric patients as well as the associated factors. The 2006 World Health Organization report called for developing a standard definition for child maltreatment and standard operational definitions for its identification [13]. In this study, we adopt the definition provided by Mathews and Collin-Vézina [14]: “Unwanted sexual contact (genital touching and fondling to penetration) while the victim is a child by legal definition and the perpetrator is in a position of relative power vis a vis the victim (e.g. parent, adult, babysitter, guardian, older child, etc.).” Barth et al. [15] have emphasized the importance of standardizing a CSA assessment method using validated psychometric tools.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Tunisia to estimate the prevalence of CSA in psychiatric outpatients and to find the associated sociodemographic and clinical factors. We hypothesized that psychiatric outpatients with CSA have a higher functional impairment, comorbidities, admissions rate to psychiatric centers, and suicidal thoughts than those without a history of CSA.

Methods

Study area and sample size

This study was conducted from January 1 to July 30, 2021. Participants were recruited from patients referred to the consultant clinic of the Department of Psychiatry, Hospital of University of Gabes. The clinic provides outpatient services to adults with psychiatric disorders. The sample size was calculated using the following formula: N=(P×Q×4)/0.02², where P is the prevalence of CSA among the Tunisian general population set at 0.1 % according to El Mhamdi et al.’s study in 2016 [16], and Q=1- P. The minimum number of samples was estimated at 111, considering a precision of 2%, a confidence interval of 95%, and a sample dropout rate of 10%.

Participants

We included the patients who met the following criteria: Age ≥18 years, a diagnosed psychiatric disorder according to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders – fifth edition (DSM-5) [17], a history of psychiatric disorders that were clinically stable for at least three months, and declaring a written consent. We excluded patients with intellectual disabilities or major cognitive impairments that hindered the completion of the questionnaires. In the end, 133 eligible psychiatric outpatients participated in our study. One author interviewed the participants immediately after the regular psychiatric consultation to confirm the results. The average duration of the interview was 30 minutes.

Measures

Socio-demographic and clinical forms

We used a pre-defined form to collect socio-demographic characteristics. Clinical data were extracted either from the participants’ medical records or from their psychiatrists.

Childhood trauma questionnaire short form (CTQ-SF)

The CTQ-SF is a self-administered questionnaire with 28 items rated on a five-point Likert scale. It is used to measure the severity of trauma during childhood. It has five sub-scales measuring different dimensions of child abuse: Physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect [18]. Participants with a score ≥8 were considered to have a history of CSA [19]. This questionnaire was translated from English into Arabic and back translated into English for linguistic adaptation. The final version was considered after comparing the two versions. In the current study, the Arabic version of the CTQ-SF had solid convergent validity and acceptable reliability for the sexual abuse subscale (Cronbach’s α=0.755).

The suicide behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R)

The SBQ-R is a self-administered questionnaire developed by Osman et al. [20] inadequate attention has been given to the development or validation of measures of past suicidal behavior. The present study examined the reliability and validity of a brief self-report measure of past suicidal behavior, the suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R to study suicide behaviors. This scale has been used for general adult populations in different countries due to acceptable reliability, brevity, ease of use, and stability [21, 22]. This instrument has four items. The first item taps into lifetime suicide ideation and suicide attempts. The second item assesses the frequency of suicide ideation over the past 12 months. The third item assesses the threat of suicide attempts. The final item assesses the risk of committing suicide in the future. The SBQ-R was translated into Arabic according to the recommendation of Wild et al. [23]. For its internal consistency, Cronbach’s α was 0.84, which was acceptable. In the present study, option 2 for item 1 was used to indicate the risk of suicide ideation, and options 4a and 4b for item 1 were used to indicate previous suicide attempts [24].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was done in the statistical package for social sciences software (SPSS) version 20. Quantitative variables were described using means and Mean±SD. For these variables, we checked the normality of data distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test. The qualitative variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies (percentages). Data were analyzed using the chi-square test, Fischer’s exact test, and independent t-test. A logistic regression analysis was applied to determine the best linear combination of factors associated with CSA. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 1 and 2.

The mean age of the participants was 45.02±11.8 years, with a sex ratio (M: F) of 1:5. The primary diagnosis was psychosis (28.6%). The SBQ-R score showed that 33.8% of participants had a history of suicide ideation, and 19.5% had a history of suicide attempt. The mean score of the sexual abuse subscale in the CTQ-SF was 5.93±2.3, ranging from 5 to 25. We found that 9.8% of participants had scores ≥8 in this subscale (n=13), corresponding to the prevalence of CSA.

The socio-demographic factors associated with the history of CSA are presented in Table 3.

We did not find a significant association between the history of CSA and the factors of age, gender, marital status, educational level, occupation, and economic status. The multivariate analysis showed that the history of CSA in psychiatric outpatients increased the risk of having a criminal record by 6.4 (AOR=6.4; 95% CI, 1.2%, 34.7%).

The clinical factors associated with the history of CSA are summarised in Table 4.

The CSA was significantly associated with a younger age at onset of psychiatric symptoms, psychiatric comorbidities, and a longer duration of psychiatric hospital stay. The history of suicide ideation and psychiatric comorbidities increased the likelihood of a history of CSA by 5.1 (AOR=5.1; 95% CI, 1.03%, 26.9%) and 5.9 (AOR=5.9; 95% CI, 1.3%, 28.8%), respectively.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that only 9.8% of outpatients had a history of CSA, which was significantly lower than the rates reported in many similar studies. This rate was 23% in a study conducted among psychiatric patients in South Korea [8], 20.7% in the U.S.[25], and 35.3% in Canada [26]. A possible explanation for this result is that, in Tunisia, due to socio-cultural factors, it is not expected to talk about sexual abuse in childhood, even to parents. Thus, the majority might not feel comfortable reporting their CSA. Therefore, the anonymous self-administered CTQ-SF can be more appropriate to estimate the prevalence of CSA in Tunisian patients. Another possible explanation is the validity of the used instrument. We examined the presence of CSA in our patients using the Arabic version of CTQ-SF. This questionnaire is the most widely used scale for measuring childhood trauma due to the ease of use and the stability of its psychometric characteristics in different cultures [27]. Studies have indicated the importance of cross-cultural adaptation for the CTQ-SF in terms of factor structure during its translation and the importance of defining positive thresholds for its sub-scales, adapted to the study population [7, 28].

We did not find a significant association between CSA history and gender, which is against the results of a similar study conducted in the UK [29]. This discrepancy can be due to the low ratio of women to men in our study (1:5) or the reluctance of men to disclose the CSA [30]. We did not find a significant association of CSA with educational level, marital status, economic status, or occupation, either. Our results showed that the patients with CSA had a higher criminal history. This result is consistent with the results of a study that reported that CSA is an independent risk factor for later antisocial behaviors [31]. This result can be explained by the fact that individuals who are victims of physical abuse during childhood tend to have aggressive behaviors towards others in adulthood. They grew up with the belief that violence can help them get what they want. The experience of sexual abuse during childhood seems to increase the risk of being a criminal in adulthood by 30%, which evokes the concept of intergenerational transmission of violence [32]. Having antisocial behaviors can be a way of self-protection for the victims of sexual abuse, a way to be independent of others and avoid intimate relationships, which are perceived as a sign of emotional weakness [33].

In the present study, the CSA was significantly associated with a younger age at onset of psychiatric symptoms and the presence of psychiatric comorbidities. This finding is consistent with findings of previous studies, which reported that the experience of childhood maltreatment was associated with subsequent onset of psychiatric disorders, psychiatric disorders’ increased risk of recurrence, resistance to treatment, and a longer treatment period [34]. We found that the CSA in psychiatric outpatients was also significantly associated with a longer duration of hospitalization in psychiatric centers. Similar results have been reported in the literature. Previous studies have reported that patients with a history of CSA were more likely to be hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals; they were 30% more likely to be hospitalized for more than ten days per year than patients without a history of CSA and were 2.5 times more likely to receive high doses of antipsychotics [35–37]. This result can be explained by the increased severity of psychiatric disorders in these patients and the frequency of psychotic episodes during decompensation.

Moreover, our results showed that CSA was significantly associated with suicide ideation, which is in agreement with other studies. This result was explained by the frequency of anxiodepressive disorders (3) due to emotional dysregulation in these patients (5), the mediating role of hopelessness (6), and the increased neurobiological vulnerability, causing the dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex, corpus callosum, and the dysregulation of cortisol secretion [38–40].

The CSA could significantly predict suicidal ideation in psychiatric patients but not their suicide attempts. Evidence from the literature concerning the role of CSA in suicide attempts is varying. Overall, suicide attempts are complicated behaviors affected by several individual, clinical, and environmental factors and should be interpreted based on the results of an overall assessment. In the U.S., results of a study showed that, although depression significantly predicted suicidal ideation, it could not significantly predict suicide attempts, which were associated with anxiety, poor impulse control, and substance abuse [41].

Given the evidence for the high prevalence of CSA among psychiatric outpatients, we recommend clinicians to inquire about CSA in psychiatric patients frequently. Strong evidence suggests that disclosure of CSA during psychotherapy may reduce PTSD symptoms [42]. Cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, and group therapy seem to be effective options for treatment [43–45].

There were some limitations in the present study. There was a lack of detailed information regarding the perpetrators of the CSA in patients, as well as information on their intensity. Also, it was not possible to study the causal links between CSA and various psychiatric diagnoses. Comparative studies using a larger sample size for each psychiatric diagnosis, including a control group, may be more suitable for studying these possible links. The lack of a validated instrument for the Tunisian culture was another limitation. The study's cross-sectional design limited the exploration of the evolutionary aspects of the associations. Longitudinal studies are recommended to better evaluate them.

Conclusion

Our study highlighted the importance of assessing the history of CSA in psychiatric patients. The multiple admissions and longer hospitalizations, the presence of suicidal thoughts, and psychiatric comorbidities can predict CSA. We emphasize the need to systematically evaluate the history of CSA in psychiatric patients to develop appropriate plans for mitigating the adverse effects of CSA on their psychiatric disorders and to ensure early and effective psychosocial care.

Our study highlighted the importance of assessing the history of CSA in psychiatric patients. The multiple admissions and longer hospitalizations, the presence of suicidal thoughts, and psychiatric comorbidities can predict CSA. We emphasize the need to systematically evaluate the history of CSA in psychiatric patients to develop appropriate plans for mitigating the adverse effects of CSA on their psychiatric disorders and to ensure early and effective psychosocial care.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Participants were informed about their right to leave the study at any time and signed a written informed consent form. Ethical approval (Code: 0459/2020) was obtained from the regional Ethics Committee CPP SUD (Committee of Person Protection), and the procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

The authors contributed equally to preparing this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Agyapong VI, Juhás M, Ritchie A, Ogunsina O, Ambrosano L, Corbett S. Prevalence rate and demographic and clinical correlates of child sexual abuse among new psychiatric outpatients in a City in Northern Alberta. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2017; 26(4):442-52. [DOI:10.1080/10538712.2017.1282573]

- Baboolal NS, Lalla S, Chai M, Curtis R, Nandwani C, Olivier L, et al. Childhood sexual abuse among outpatients attending adult psychiatric outpatient clinics: A case-control study. The West Indian Medical Journal. 2007; 56(2):152–8. [DOI:10.1590/S0043-31442007000200009] [PMID]

- Bedi S, Nelson EC, Lynskey MT, McCutcheon VV, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Risk for suicidal thoughts and behavior after childhood sexual abuse in women and men: Childhood sexual abuse. Suicide & life-Threatening Behavior. 2011; 41(4):406-15. [DOI:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00040.x] [PMID]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2014; 186(9):E324-32. [DOI:10.1503/cmaj.131792] [PMID]

- Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychological Medicine. 2004; 34(8):1475-82. [DOI:10.1017/S003329170400265X] [PMID]

- Spokas M, Wenzel A, Stirman SW, Brown GK, Beck AT. Suicide risk factors and mediators between childhood sexual abuse and suicide ideation among male and female suicide attempters. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009; 22(5):467-70. [DOI:10.1002/jts.20438] [PMID]

- Zhang TH, Chow A, Wang LL, Yu JH, Dai YF, Lu X, et al. Childhood maltreatment profile in a clinical population in China: A further analysis with existing data of an epidemiologic survey. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013; 54(7):856-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.03.014] [PMID]

- Kim D, Park SC, Yang H, Oh DH. Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form for Psychiatric Outpatients. Psychiatry Investigation. 2011; 8(4):305-11. [DOI:10.4306/pi.2011.8.4.305] [PMID]

- Rossiter A, Byrne F, Wota AP, Nisar Z, Ofuafor T, Murray I, et al. Childhood trauma levels in individuals attending adult mental health services: An evaluation of clinical records and structured measurement of childhood trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015; 44:36-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.001] [PMID]

- Teicher MH, Gordon JB, Nemeroff CB. Recognizing the importance of childhood maltreatment as a critical factor in psychiatric diagnoses, treatment, research, prevention, and education. Molecular Psychiatry. 2022; 27(3):1331-8. [DOI:10.1038/s41380-021-01367-9] [PMID]

- Hajri A, Romdhane IB, Mrabet A, Labbane R. Childhood trauma in bipolar disorder: A North-African Study. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2022; 27(5):483-5. [Link]

- Soussia RB, Omezzine RG, Bouali W, Zemzem M, Bouslah S, Zarrouk L, et al. [Epidemioclinical and legal aspects of sexual abuse among minors in Monastir, Tunisia (French])]. 2021; 38:105. [DOI:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.105.21766] [PMID]

- World Health Organization. Preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Link]

- Mathews B, Collin-Vézina D. Child Sexual Abuse: Toward a conceptual model and definition. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2019; 20(2):131-48. [DOI:10.1177/1524838017738726] [PMID]

- Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T. The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health. 2013; 58(3):469-83. [DOI:10.1007/s00038-012-0426-1] [PMID]

- E1 Mhamdi S, Lemieux A, Abroug H, Ben Salah A, Bouanene I, Ben Salem K, et al. Childhood exposure to violence is associated with risk for mental disorders and adult’s weight status: A community-based study in Tunisia. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England).2019; 41(3):502-10. [DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdy149] [PMID]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Virginia: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Link]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Link]

- López-Mongay D, Ahuir M, Crosas JM, Navarro JB, Monreal JA, Obiols JE, et al. The effect of child sexual abuse on social functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Journal of Interpersonal Violenc. 2021; 36(7-8):NP3480-NP3494. [Link]

- Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R):Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001; 8(4):443-54. [DOI:10.1177/107319110100800]

- Amini-Tehrani M, Nasiri M, Jalali T, Sadeghi R, Ghotbi A, Zamanian H. Validation and psychometric properties of Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) in Iran. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020; 47:101856. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101856]

- Batterham PJ, Ftanou M, Pirkis J, Brewer JL, Mackinnon AJ, Beautrais A, et al. A systematic review and evaluation of measures for suicidal ideation and behaviors in population-based research. Psychological Assessment. 2015; 27(2):501-12. [DOI:10.1037/pas0000053] [PMID]

- Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in Health. 2005; 8(2):94-104. [DOI:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x] [PMID]

- Rahman ME, Al Zubayer A, Al Mazid Bhuiyan MR, Jobe MC, Ahsan Khan MK. Suicidal behaviors and suicide risk among Bangladeshi people during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online cross-sectional survey. Heliyon. 2021; 7(2):e05937. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05937] [PMID]

- Shi L. Childhood abuse and neglect in an outpatient clinical sample: Prevalence and impact. he American Journal of Family Therapy. 2013; 41(3):198-211. [DOI:10.1080/01926187.2012.677662]

- Kealy D, Lee E. Childhood trauma among adult clients in Canadian community mental health services: Toward a trauma-informed approach. International Journal of Mental Health. 2018; 47(4):284-97. [DOI:10.1080/00207411.2018.1521209]

- Schmidt MR, Narayan AJ, Atzl VM, Rivera LM, Lieberman AF. Childhood maltreatment on the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Scale versus the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) in a Perinatal Sample. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2020; 29(1):38-56. [DOI:10.1080/10926771.2018.1524806]

- Devi F, Shahwan S, Teh WL, Sambasivam R, Zhang YJ, Lau YW, et al. The prevalence of childhood trauma in psychiatric outpatients. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2019; 18:15. [DOI:10.1186/s12991-019-0239-1] [PMID]

- Werbeloff N, Hilge Thygesen J, Hayes JF, Viding EM, Johnson S, Osborn DPJ. Childhood sexual abuse in patients with severe mental Illness: Demographic, clinical and functional correlates. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2021; 143(6):495-502. [DOI:10.1111/acps.13302] [PMID]

- Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment. 2011; 16(2):79-101. [DOI:10.1177/1077559511403920] [PMID]

- Swanston HY, Parkinson PN, O'Toole BI, Plunkett AM, Shrimpton S, Kim Oates R. Juvenile crime, aggression and delinquency after sexual abuse: A longitudinal study. The British Journal of Criminology. 2003; 43(4):729-49. [DOI:10.1093/bjc/43.4.729]

- Widom CS.Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1989; 106(1):3-28. [DOI:10.1037//0033-2909.106.1.3] [PMID]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, et al. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001; 158(11):1878–83. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878] [PMID]

- Arnow BA. Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcomes, and medical utilization. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004; (Suppl 12):10-5. [PMID]

- Schenkel LS, Spaulding WD, DiLillo D, Silverstein SM. Histories of childhood maltreatment in schizophrenia: Relationships with premorbid functioning, symptomatology, and cognitive deficits. Schizophrenia Research. 2005; 76(2-3):273-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.003] [PMID]

- Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Essock SM, Osher FC, et al. Interpersonal Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with severe mental illness: Demographic, clinical, and health correlates. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004; 30(1):45-57. [DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007067] [PMID]

- Schneeberger AR, Muenzenmaier K, Castille D, Battaglia J, Link B. Use of psychotropic medication groups in people with severe mental illness and stressful childhood experiences. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2014; 15(4):494-511. [DOI:10.1080/15299732.2014.903550] [PMID]

- Andersen SL, Tomada A, Vincow ES, Valente E, Polcari A, Teicher MH. Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2008; 20(3):292-301. [DOI:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.3.292]

- Rao U, Chen LA, Bidesi AS, Shad MU, Thomas MA, Hammen CL. Hippocampal changes associated with early-life adversity and vulnerability to depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2010; 67(4): 357–64. [DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.017] [PMID]

- Lopez-Castroman J, Melhem N, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, et al. Early childhood sexual abuse increases suicidal intent. World Psychiatry. 2013; 12(2):149-54. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20039] [PMID]

- Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010; 15(8):868-76. [DOI:10.1038/mp.2009.29] [PMID]

- Bradley RG, Follingstad DR. Utilizing disclosure in the treatment of the sequelae of childhood sexual abuse: A theoretical and empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001; 21(1):1-32.[DOI:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00077-5] [PMID]

- House AS. Increasing the Usability of Cognitive Processing Therapy for Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2006; 15(1):87-103. [DOI:10.1300/J070v15n01_05] [PMID]

- Mendes DD, Mello MF, Ventura P, Passarela Cde M, Mari Jde J. A systematic review on the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2008; 38(3):241-59. [DOI:10.2190/PM.38.3.b] [PMID]

- Kreidler M. Group therapy for survivors of childhood sexual abuse who have chronic mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric nursing. 2005; 19(4):176-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.apnu.2005.05.003] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2023/08/2 | Accepted: 2023/12/21 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2023/08/2 | Accepted: 2023/12/21 | Published: 2024/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |