Mon, Nov 24, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 29, Issue 2 (Summer 2023)

IJPCP 2023, 29(2): 216-235 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ikram A, Anwar Lashari S, Anwar Lashari T. Professional Quality of Life, Empathy, and Coping Strategies of Young Clinical Psychologists in Lahore, Pakistan. IJPCP 2023; 29 (2) :216-235

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3910-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3910-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Riphah International University Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan.

2- School of Applied Psychology, Social Work and Policy, Sintok, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Kedah, Malaysia. ,sanalasharisana@gmail.com

3- Department of Computing, School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, National University of Sciences and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan.

2- School of Applied Psychology, Social Work and Policy, Sintok, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Kedah, Malaysia. ,

3- Department of Computing, School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, National University of Sciences and Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Keywords: Professional quality of life (ProQoL), Compassion fatigue, Burnout, Pakistan, Coping skills

Full-Text [PDF 6194 kb]

(673 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2837 Views)

Full-Text: (1220 Views)

Introduction

Empathy is defined as the skill to emotionally understand how other people feel, see things from their point of view, and put yourself in their shoes. A study showed that doctors with higher empathy had lower emotional exhaustion. Empathy’s cognitive component (Perspective-taking) is related to greater personal accomplishment [1]. People respond to emotional and physical effects of stress by engaging in activities that are intended to reduce their stress levels [2]. These behaviors are called coping mechanisms. Coping mechanisms are the actions to regulate, tolerate, or reduce stressful situations. There are two coping mechanisms: Problem-focused and emotion-focused. Problem-focused strategies involve actions to identify the cause of the problem. Active coping, planning, and suppression of competing activities are examples of this style. Emotion-focused strategies are used to reduce the negative feelings related to the problem. Positive reframing, acceptance, turning to religion, and humor are examples of this style. Escaping, distancing, or avoidance are other ways of coping with stressful situations and involve either psychological or physical actions [3].

The term professional quality of life (ProQoL) refers to both positive and negative emotions that a person may experience while working. Compassion satisfaction (CS) is the positive aspect and compassion fatigue (CF) is the negative aspect of ProQoL. The CS refers to one’s feeling of happiness in relation to her/his job helping others. People with CS feel that they can learn new tools and procedures. They enjoy positive thoughts, want to carry on their job and have faith that they can make a difference. The CS involves a pure altruism and contains feelings of satisfaction with supporting others efficiently [4]. The CF has two components. The first component is burnout (BO) which includes feelings such as anger, exhaustion, sadness, and frustration. The second component is secondary traumatic stress (STS) which is a negative mood which is related to work-related stress resulted from secondary contact with people who have experienced traumatic events. The STS can be associated with fear, sleep problems, disturbing images, or avoiding cues of the person’s distressing experiences [4]. The CS, BO, and STS are the key constructs of ProQoL, since it influences or is influenced by professional well-being and performance [5]. According to Stamm [4], the overall concept of ProQoL is related to three main factors: The work environment’s characteristics, the person’s characteristics, and the person’s exposure to primary and secondary trauma in the workplace. This applies to paid workers such as medical personnel.

Working in a hospital can put a heavy psychological burden on clinical psychologists, due to constant exposure to patients, therapeutic setbacks, clients’ negative actions and non-cooperation, and a lack of necessary resources. These factors contribute to health risks that can lower their quality of life [6]. In a recent review study of 32 articles for finding the predictors of CF in professionals, Thomas and Otis [7] concluded that caseload (amount of time spent with trauma victims) and type of clinical setting were the only predictors of CF. However, when the subjective traits of professionals were investigated, their traumatic history and capacity for empathy were consistently found to be risk factors for CF. Clinical psychologists are likely to deal with several traumatic events daily. Figley [8] reported that with higher exposure to disturbing situations, the possibility of CF in psychotherapists increases by 27%. Thompson et al. [9] showed that the rate of CF was higher in female psychologists compared to male psychologists, and those with CF had lower compassion satisfaction and feeling of individual success.

Clinical therapists who treat traumatized patients are more likely to experience changes in their own psychological functioning. A change in psychological functioning can include changes in reactions to environmental conditions that is correlated with the experiences of their patients and the negative effects that clinician witness. These negative reactions may include avoidance of the traumatic event, feeling of horror, guilt, anger, sadness, detachment, or dread, and they may even result in burnout and counter-transference [10]. Moreover, a study reported that empathy and coping strategies were the predictors of ProQoL in Australian registered migration agents. Low empathy and maladaptive coping strategies predicted CF, while high empathy and adaptive coping predicted CS [11]. The findings of Justin et al. [12] showed that hardiness and religious coping strategies predicted higher CS, whereas commitment, behavior disengagement, self-distraction, and humor coping strategies were likely to predict higher CF among clinical psychologists.

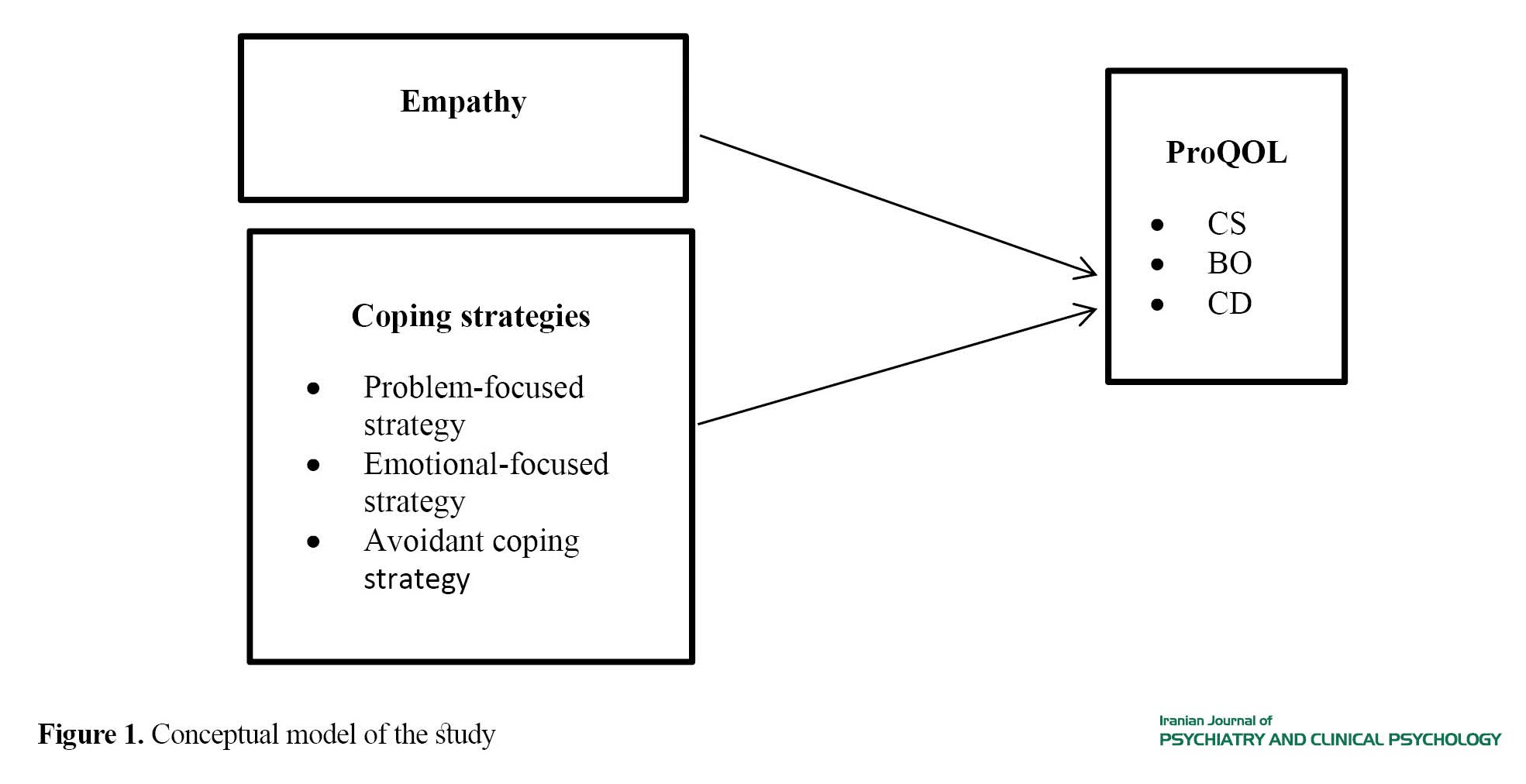

Findings of studies in Pakistan have shown that mental illness is a prevalent concern and with the growing attention, many people are looking for psychological help [13]. In this regard, mental health professionals involving both clinical psychologists and psychiatrists in Pakistan are exposed to individuals with stressful life events, anxiety, and several mental health problems, and their job demands unconditional help, empathy, active listening, and emotional understanding during counseling sessions. Therefore, they are at higher risk of internalizing negative emotions which cause CF and burnout and ultimately affect their ProQoL [14]. Hence, attention should be paid to how much the clinical psychologists’ practice affects their functioning, and how they deal with it, and recognize positive behavioral strategies to increase their satisfaction and quality of life. Hence, this study aims to assess the relationship between ProQoL, empathy, and coping mechanisms in young clinical psychologists in Pakistan. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of the study. It has been reported that years of work experience and adaptive coping mechanisms are reliable indicators of ProQoL. Years of work experience has been found to be positively connected with CS and negatively associated with burnout in among therapists. Therefore, the clinical psychologists’ ProQoL, empathy, and coping strategies are important to study in a single model because they experience high emotional demands and mental health issues more recurrently than the general population and their years of work experience can also be a predictor of ProQoL [15]. Preacher et al. [16] stated that a third variable is considered as a moderator, if the strength of the relationship between two variables depends on the third variable. The present study considered years of experience as a moderator (Figure 2) based on the following hypotheses: [17] Years of work experience (a moderator) influence the direction or strength of the relationship between empathy (a predictive variable) and ProQoL (a dependent variable);

Years of work experience affects individual or contextual factors that alter the relationship between empathy and ProQoL;

Both empathy and years of work experience are elements in the experiment manipulated with specific treatments.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a descriptive-correlational survey. In Lahore, Pakistan, there are more than 100 registered young clinical psychologists working in many public and private hospitals [18]. Out of these, 80 young clinical psychologists were selected as the study samples using a purposive sampling method. GPower software was used to calculate the sample size. Of 90 questionnaires distributed, 10 questionnaires were discarded due to missing data and no response from participants. Among participants, 38.8% had a diploma in advanced diploma in clinical psychology, 57.5% had master’s degree and 3.8% had Ph.D. The work experience of 75% of participants was 1-5 years, while the remaining 25% had a 6-10 years of experience. The participants’ age ranged 23-37 years (Mean=30 years). Most of participants (56.2%) were female. The inclusion criteria were: experience of 1-10 years, license in Clinical psychology, and working in a hospital in Lahore daily. Exclusion criteria were: not having a BS Hons Psychology degree, and work experience >10 years.

Instruments

The Board of Advanced Studies and Research approved this research. After obtaining permission from the hospital authorities and informed consent from the participants, the questionnaires were distributed which were a demographic form, Toronto empathy questionnaire (TEQ), Brief COPE inventory, and the ProQoL scale. First a pilot study was conducted with ten participants. The data was collected in person or via email from the participants during their working hours. Before filling out the questionnaires, the participants were explained about the study purpose and they were assured that their data would only be used for research purposes and that their information would be kept confidential. The demographic form surveys gender, age, educational level, marital status, years of work experience, and working hours per day. The TEQ consists of 16 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Higher scores show a great level of empathy while scores <45 show a low empathy. Construct validity of TEQ has been confirmed through association with other questionnaires of empathy (e.g. with the empathy questionnaire; r=0.80). The internal consistency of TEQ is high, ranging from α= 0.85 to 0.87, and its test-retest reliability is r=0.81 [4]. A good internal consistency (α=0.822) for TEQ was obtained in our study. The Brief COPE inventory is a self-report questionnaire that is used to assess coping mechanisms in reaction to a particular situation. It has 28 items and 14 subscales including self-distraction, active coping, posi- tive reframing, planning, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, venting, self-distraction, acceptance, self- blame, behavioral disengagement, humor, denial, religion, and substance use. Following the instructions, the participants rated the items on a scale from 1 to 4. The internal consistency for the 14 subscales ranges from 0.57 to 0.90 [4]. A good internal consistency (α=0.756) was obtained for this inventory in this study. The ProQoL scale has three subscales of BO, CF, and CS, and 30 items scored on a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). A high score show a high level. Cronbach’s alpha for these subscales is 0.88, 0.75, and 0.81, respectively [4]. An acceptable internal consistency (α=0.639) was obtained in this study.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed by in SPSS software, version 25 and were reported using mean and standard deviation. To examine the association between empathy, coping strategies, and ProQoL, Pearson correlation test was used. To examine the effect of demographic variables on these variables, categorical regression analysis was done by transforming demographic variables into dummy variables. The moderating role of work experience in the relationship between empathy and ProQoL was also tested.

Results

The correlation coefficients between the study variables as well as the mean scores of these variables are presented in Table 1.

There was a weak positive correlation among empathy, problem-focused coping strategies, and emotion-focused coping strategies (r=0.36 and 0.46; P=0.01). There was a moderate positive significant correlation between empathy and CS (r=0.47, P=0.01); a very weak positive significant correlation exists between empathy and BO (r=0.15, P=0.01); and a weak positive significant correlation between CS and problem-focused coping strategies (r=0.38, P=0.01). The relationship among problem-focused coping strategies, BO, and CF was weak and negative (r=-0.10 and 0.16, P=0.01). There was a weak positive significant correlation between emotion-focused coping strategies and CS (r=0.12, P=0.01). There was a positive and very weak correlation between BO and Avoidance coping strategies (r=0.6, P=0.05). The relationship between Avoidance coping strategies and CF was relatively weak and positive (r=0.15, P=0.05).

Categorical regression results

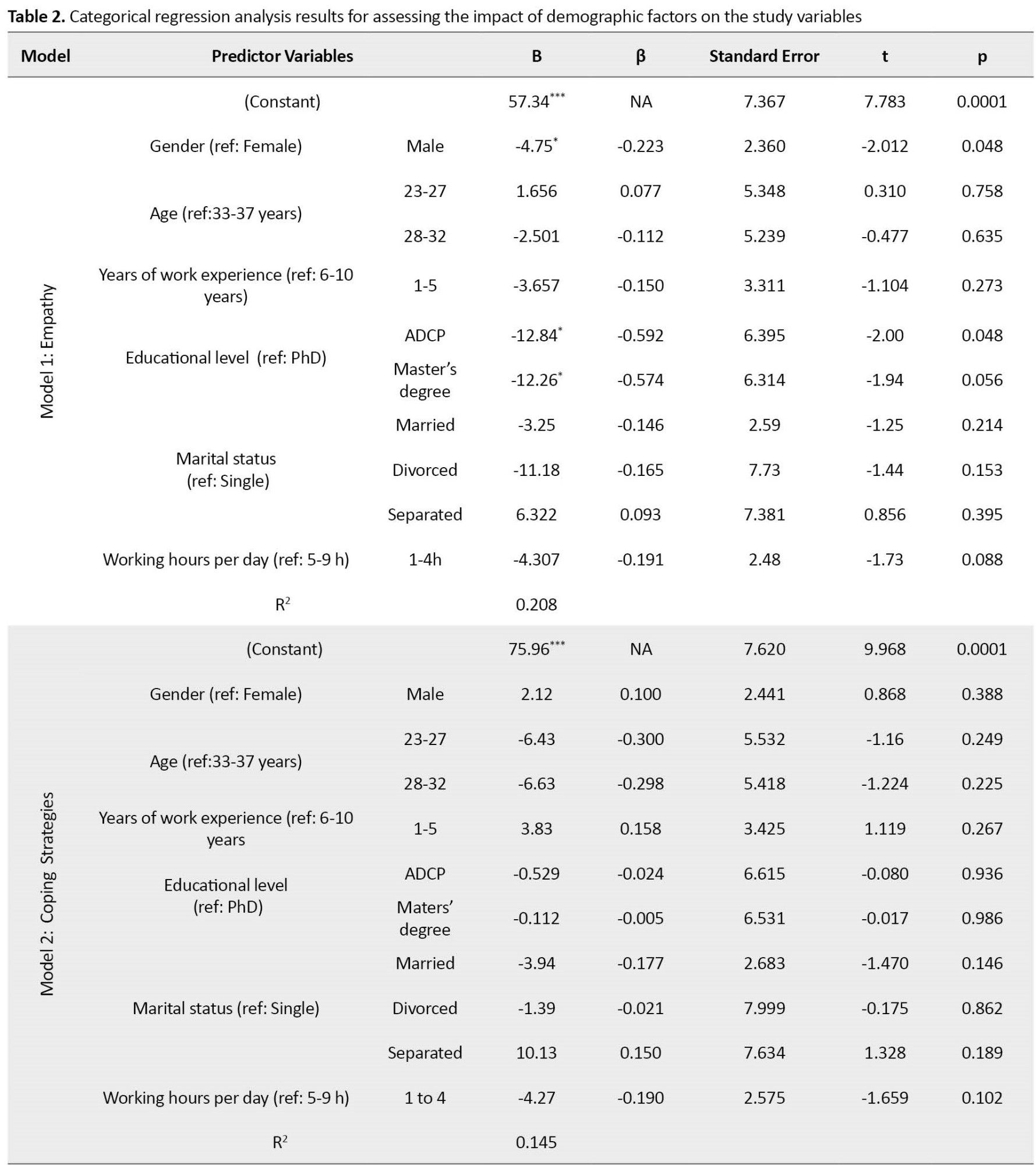

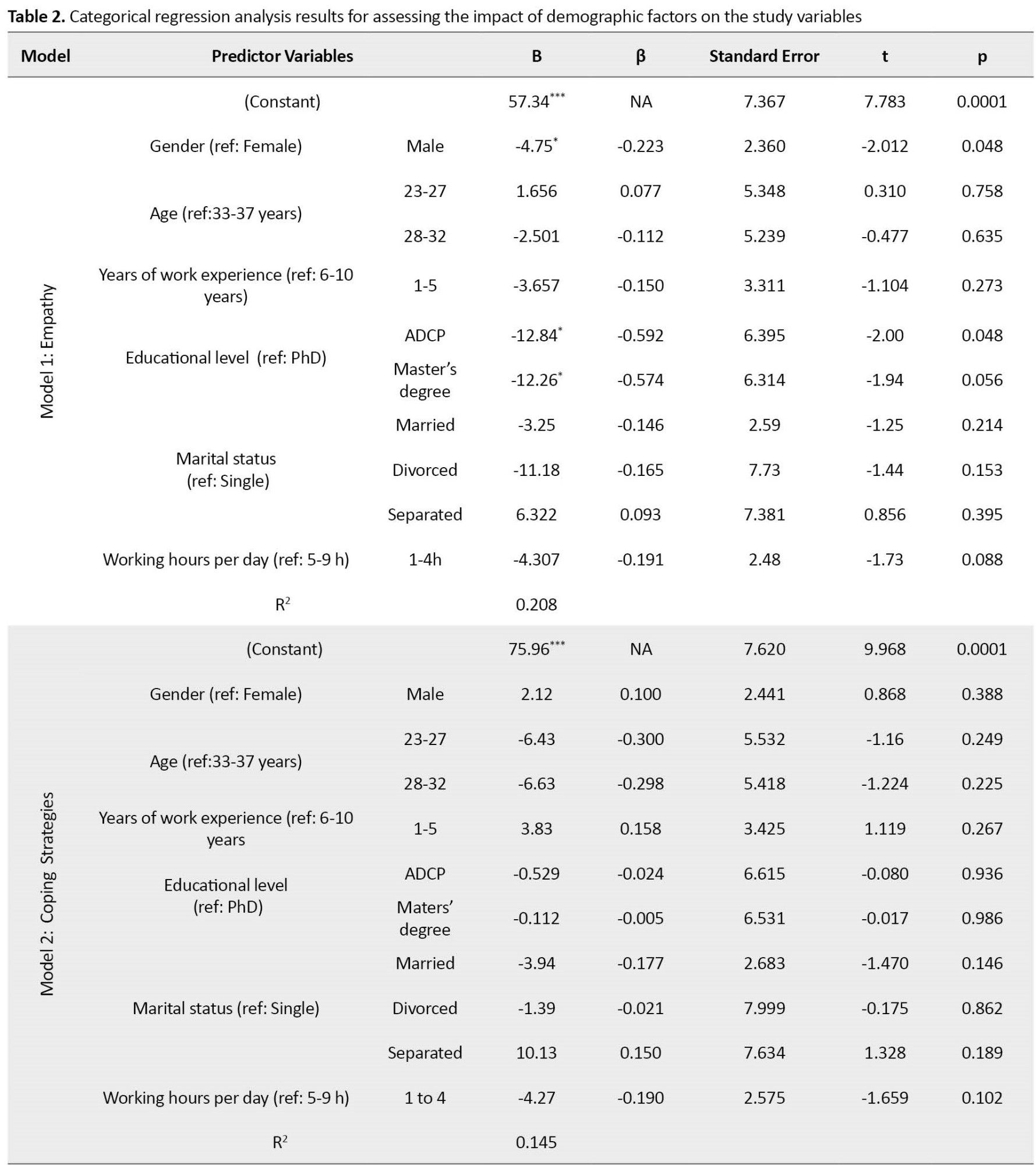

Table 2 shows the results for the effect of demographic variables (predictor variables) on study variables.

Model 1 shows the effect of demographic variables on empathy. The R2 value of 0.208 indicates that predictor variables explained about 20% of changes in empathy; F (10,69) =1.808. Gender and educational level had a significant impact on empathy (P<0.05), where females and those with PhD degree had more empathy. Age, years of work experience, marital status, and working hours per day had no significant impact on empathy. Model 2 shows the effect of demographic variables on coping strategies. The R2 value of 0.145 indicates that predictor variables explained about 14% of changes in coping strategies; F (10,69) =1.173. There was no significant impact of demographic variables on coping strategies compared to the reference group. Model 3 shows the effect of demographic variables on ProQoL. The R2 value of 0.234 indicates that the predictor variables explained about 23% of changes in ProQoL; F(10,69) =2.103. Age had a significant impact on ProQoL (P<0.05), where people aged 28-32 years of age had good ProQoL compared to the reference group. Gender, years of work experience, marital status, and working hours per day had no significant impact on ProQoL.

Moderation analysis results

Table 3 indicates the results assessing the moderating role of work experience in the relationship empathy and ProQoL.

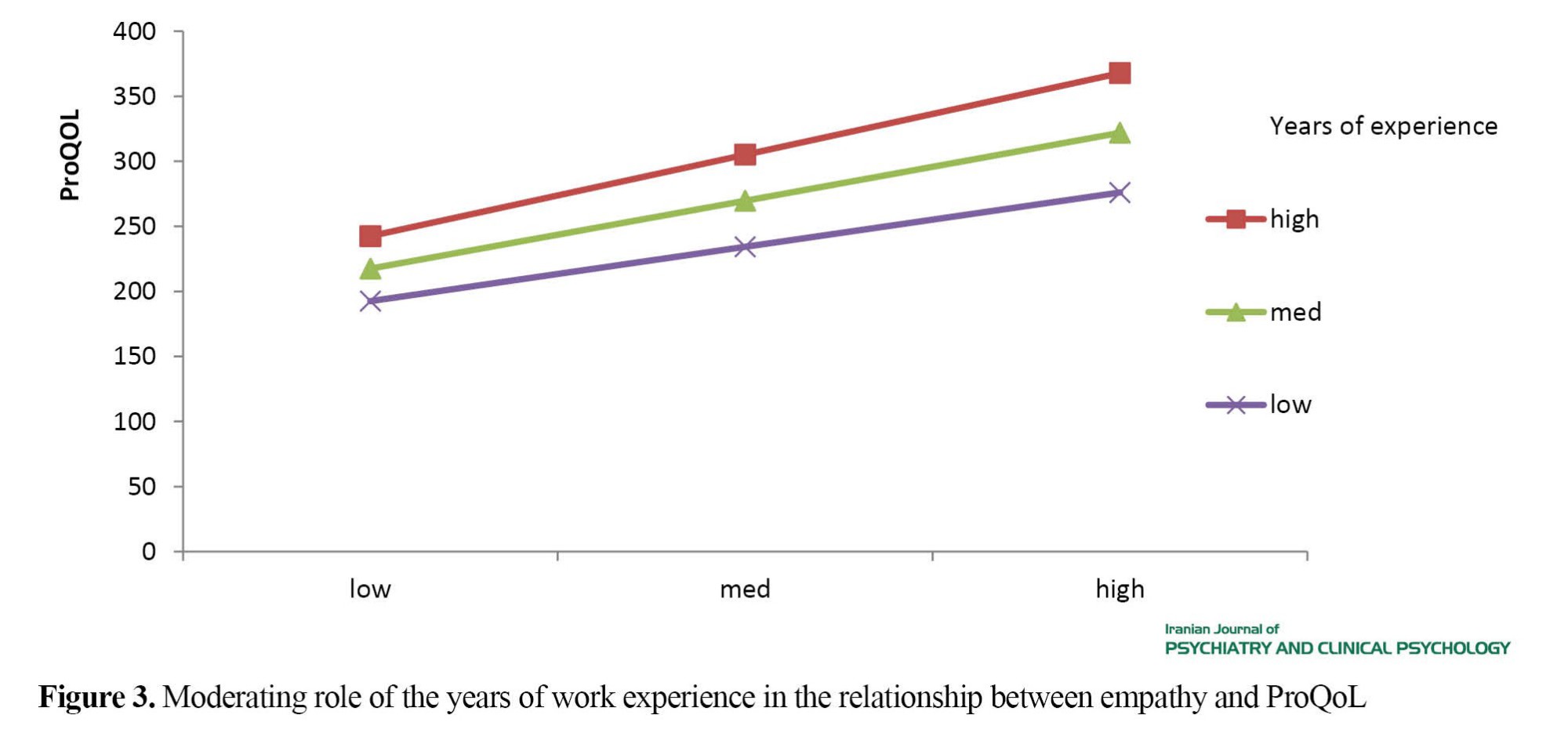

In Model 1, the R² value of 0.79 indicated that the predictor explained 79% of variance in empathy; F (2,27)=3.303, P>0.05. The finding showed that (β=0.22, P<0.01) and work experience (β=-0.16, P<0.05) predicted ProQoL. In Model 2, R² value of 0.14 indicated that the predictor explained 14% variance in ProQoL; F (1.76) =0.02, P<0.001. The finding revealed that empathy (β=2.10, P<0.01) and work experience (β=-0.15, P>0.05) and empathy×work experience (β=0.256, P>0.01) predicted ProQoL. The ∆R² value of 0.06 revealed that work experience explained 6% of changes in empathy and ProQoL; ∆F (2, 77)=3.303, p<0.05. Finding show that work experience in years moderates the relationship between empathy and professional quality of life.

Simple slope analysis indicated that years of work experience acted as a buffer to increase the correlation between empathy and ProQoL (P<0.001) (Figure 3).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship among ProQoL, coping strategies, and empathy of clinical psychologists in Lahore, Pakistan. According to the results, there was a significant positive relationship between empathy, problem-focused coping strategies, and emotion-focused coping strategies. Problem-focused coping strategies include active managing, planning, and suppression of competing activities. Emotion-focused coping strategies include positive reframing, acceptance, religion, and humor. We found no significant relationship between empathy and avoidance coping strategies. These findings support the results of previous studies. Varadarajan et al. [19] found that perceived empathy, or one’s perceived capacity for empathy, negatively correlated with maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as behavioral disengagement). Sun et al. [20] reported that higher empathy was related to the usage of more adaptive coping strategies (active coping, positive reframing, planning, and acceptance), social support (instrumental and emotional support), and fewer maladaptive coping strategies (denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement, and self-blame).

Current study indicated a weak positive relationship between CS and problem-focused coping strategies. Previous research showed a positive relationship between problem-focused coping and job satisfaction. The amount of work, problem-focused coping, peer support, family and friend care, and CF all had an impact on job satisfaction [21]. There was a weak negative association between problem-focused coping strategies, BO, and CF. Other studies also showed a weak link between BO and problem-focused coping mechanisms. Higher scores in the instruments, which are a sign of successful use of inner resources for problem-solving, were seen as representing directives of job demands [22, 23]. In our study, there was a weak positive association between CS and emotion-focused coping strategies. The association between emotion-focused coping strategies, BO, and CF was not significant. These results are in contrast to the results of a previous research, which revealed that burnout might be caused by higher use of emotion-focused coping strategies and a lower problem-focused and avoidance coping strategies [24]. This discrepancy can be due to difference in the study population and various coping mechanisms used by clinical psychologists. There was a weak positive association between avoidance coping, BO, and CF. The previous study demonstrated that avoidance coping and CF had a significant relationship with each another. Better emotion-focused coping and lower problem-focused and avoidance coping may contribute to burnout [24]. Our study is consistent with previous studies focused on different strategies that involve problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping strategies. In Justin et al.’s [12] study on clinical psychologists, a significant positive relationship was observed among hardiness, control, commitment, active, positive reframing, planning, religious coping strategies, and CS; a significant negative relationship was seen between denial, and behavior disengagement coping strategies and CS; a significant positive relationship was observed between self-distraction, denial, and behavior disengagement coping strategies, CF, and burnout; and a significant negative relationship between hardiness, challenge, and commitment coping strategy, CF, and burnout [12]. In our study, empathy, CS, and BO had a moderate positive association with one another, but there was no significant association between CF and empathy. This is consistent with the results of Varadarajan, et al. [19], who found that the association between empathy, CF, and CS change significantly over time. Another research showed that empathy and adaptive coping strategies had a significant positive relationship with CS, and a significant negative relationship with burnout [25].

According to the present study, the relationship between empathy and ProQoL was moderated by clinical psychologists’ years of work experience. Various possible reasons can be behind this findings. Due to the pressure of the system, clinical psychologists are facing an increased stress and BO at workplace. Due to an increase in the number of patients and declining resources, they work long hours and feel less able to meet patient needs. Their compassion fatigue and an overall reduction in ProQoL can also be due to prolonged exposure to patients who are unwell, injured, suffering, or dying. These findings are consistent with a research in which pediatric nurses under the age of 40 and with 6–10 years of experience, showed a higher degree of burnout and a lower degree of compassion fulfillment [26].

To encourage healthy behaviors and enhance psychological health, a culture of health needs to be created. Good sleep hygiene, social support, mindfulness, reflective counseling, a manageable workload, and flexibility to manage family-work balance can promote a culture of health. Good sleep hygiene is a crucial factor in preventing burnout and boosting individual resilience [27]. According to social support studies, therapists who have solid meaningful relationships (both personal and professional) are less likely to burn out and be sad. Two emotional health interventions that have been shown to reduce burnout and foster resilience are mindfulness therapy and stress management technique [28].

Limitations and recommendations

The researcher faced some limitations in the present study. Since the study design was cross-sectional, causal relathionships could not be determined. The data was only collected from one city and participants were mostly females, which reduce the generalizability of results. Moreover, this research used self-report tools that may contain biases in responses; therefore, other measures such as interviews with colleagues and family members can be used in future studies.

The results of this study suggest that awareness is crucial for stress management and reduction of compassion fatigue. Hence, experimental studies can be done to develop rules that can help prevent burnout and compassion fatigue in healthcare providers. Hence, mediation and educational programs can be done to improve knowledge of adaptive problem-focused coping in clinical psychologists and even in the administrative staff of hospitals.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study objectives were explained to them. They were free to leave the study at any time and were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of the second author in Clinical Psychology. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, and initial draft preparation: Areeba Ikram; Methodology, writing, editing & review: Areeba Ikram and Sana Anwar Lashari; Funding Acquisition: Sana Anwar Lashari and Tahira Anwar Lashari; Supervision: Sana Anwar Lashari.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Refrences

Empathy is defined as the skill to emotionally understand how other people feel, see things from their point of view, and put yourself in their shoes. A study showed that doctors with higher empathy had lower emotional exhaustion. Empathy’s cognitive component (Perspective-taking) is related to greater personal accomplishment [1]. People respond to emotional and physical effects of stress by engaging in activities that are intended to reduce their stress levels [2]. These behaviors are called coping mechanisms. Coping mechanisms are the actions to regulate, tolerate, or reduce stressful situations. There are two coping mechanisms: Problem-focused and emotion-focused. Problem-focused strategies involve actions to identify the cause of the problem. Active coping, planning, and suppression of competing activities are examples of this style. Emotion-focused strategies are used to reduce the negative feelings related to the problem. Positive reframing, acceptance, turning to religion, and humor are examples of this style. Escaping, distancing, or avoidance are other ways of coping with stressful situations and involve either psychological or physical actions [3].

The term professional quality of life (ProQoL) refers to both positive and negative emotions that a person may experience while working. Compassion satisfaction (CS) is the positive aspect and compassion fatigue (CF) is the negative aspect of ProQoL. The CS refers to one’s feeling of happiness in relation to her/his job helping others. People with CS feel that they can learn new tools and procedures. They enjoy positive thoughts, want to carry on their job and have faith that they can make a difference. The CS involves a pure altruism and contains feelings of satisfaction with supporting others efficiently [4]. The CF has two components. The first component is burnout (BO) which includes feelings such as anger, exhaustion, sadness, and frustration. The second component is secondary traumatic stress (STS) which is a negative mood which is related to work-related stress resulted from secondary contact with people who have experienced traumatic events. The STS can be associated with fear, sleep problems, disturbing images, or avoiding cues of the person’s distressing experiences [4]. The CS, BO, and STS are the key constructs of ProQoL, since it influences or is influenced by professional well-being and performance [5]. According to Stamm [4], the overall concept of ProQoL is related to three main factors: The work environment’s characteristics, the person’s characteristics, and the person’s exposure to primary and secondary trauma in the workplace. This applies to paid workers such as medical personnel.

Working in a hospital can put a heavy psychological burden on clinical psychologists, due to constant exposure to patients, therapeutic setbacks, clients’ negative actions and non-cooperation, and a lack of necessary resources. These factors contribute to health risks that can lower their quality of life [6]. In a recent review study of 32 articles for finding the predictors of CF in professionals, Thomas and Otis [7] concluded that caseload (amount of time spent with trauma victims) and type of clinical setting were the only predictors of CF. However, when the subjective traits of professionals were investigated, their traumatic history and capacity for empathy were consistently found to be risk factors for CF. Clinical psychologists are likely to deal with several traumatic events daily. Figley [8] reported that with higher exposure to disturbing situations, the possibility of CF in psychotherapists increases by 27%. Thompson et al. [9] showed that the rate of CF was higher in female psychologists compared to male psychologists, and those with CF had lower compassion satisfaction and feeling of individual success.

Clinical therapists who treat traumatized patients are more likely to experience changes in their own psychological functioning. A change in psychological functioning can include changes in reactions to environmental conditions that is correlated with the experiences of their patients and the negative effects that clinician witness. These negative reactions may include avoidance of the traumatic event, feeling of horror, guilt, anger, sadness, detachment, or dread, and they may even result in burnout and counter-transference [10]. Moreover, a study reported that empathy and coping strategies were the predictors of ProQoL in Australian registered migration agents. Low empathy and maladaptive coping strategies predicted CF, while high empathy and adaptive coping predicted CS [11]. The findings of Justin et al. [12] showed that hardiness and religious coping strategies predicted higher CS, whereas commitment, behavior disengagement, self-distraction, and humor coping strategies were likely to predict higher CF among clinical psychologists.

Findings of studies in Pakistan have shown that mental illness is a prevalent concern and with the growing attention, many people are looking for psychological help [13]. In this regard, mental health professionals involving both clinical psychologists and psychiatrists in Pakistan are exposed to individuals with stressful life events, anxiety, and several mental health problems, and their job demands unconditional help, empathy, active listening, and emotional understanding during counseling sessions. Therefore, they are at higher risk of internalizing negative emotions which cause CF and burnout and ultimately affect their ProQoL [14]. Hence, attention should be paid to how much the clinical psychologists’ practice affects their functioning, and how they deal with it, and recognize positive behavioral strategies to increase their satisfaction and quality of life. Hence, this study aims to assess the relationship between ProQoL, empathy, and coping mechanisms in young clinical psychologists in Pakistan. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of the study. It has been reported that years of work experience and adaptive coping mechanisms are reliable indicators of ProQoL. Years of work experience has been found to be positively connected with CS and negatively associated with burnout in among therapists. Therefore, the clinical psychologists’ ProQoL, empathy, and coping strategies are important to study in a single model because they experience high emotional demands and mental health issues more recurrently than the general population and their years of work experience can also be a predictor of ProQoL [15]. Preacher et al. [16] stated that a third variable is considered as a moderator, if the strength of the relationship between two variables depends on the third variable. The present study considered years of experience as a moderator (Figure 2) based on the following hypotheses: [17] Years of work experience (a moderator) influence the direction or strength of the relationship between empathy (a predictive variable) and ProQoL (a dependent variable);

Years of work experience affects individual or contextual factors that alter the relationship between empathy and ProQoL;

Both empathy and years of work experience are elements in the experiment manipulated with specific treatments.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a descriptive-correlational survey. In Lahore, Pakistan, there are more than 100 registered young clinical psychologists working in many public and private hospitals [18]. Out of these, 80 young clinical psychologists were selected as the study samples using a purposive sampling method. GPower software was used to calculate the sample size. Of 90 questionnaires distributed, 10 questionnaires were discarded due to missing data and no response from participants. Among participants, 38.8% had a diploma in advanced diploma in clinical psychology, 57.5% had master’s degree and 3.8% had Ph.D. The work experience of 75% of participants was 1-5 years, while the remaining 25% had a 6-10 years of experience. The participants’ age ranged 23-37 years (Mean=30 years). Most of participants (56.2%) were female. The inclusion criteria were: experience of 1-10 years, license in Clinical psychology, and working in a hospital in Lahore daily. Exclusion criteria were: not having a BS Hons Psychology degree, and work experience >10 years.

Instruments

The Board of Advanced Studies and Research approved this research. After obtaining permission from the hospital authorities and informed consent from the participants, the questionnaires were distributed which were a demographic form, Toronto empathy questionnaire (TEQ), Brief COPE inventory, and the ProQoL scale. First a pilot study was conducted with ten participants. The data was collected in person or via email from the participants during their working hours. Before filling out the questionnaires, the participants were explained about the study purpose and they were assured that their data would only be used for research purposes and that their information would be kept confidential. The demographic form surveys gender, age, educational level, marital status, years of work experience, and working hours per day. The TEQ consists of 16 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Higher scores show a great level of empathy while scores <45 show a low empathy. Construct validity of TEQ has been confirmed through association with other questionnaires of empathy (e.g. with the empathy questionnaire; r=0.80). The internal consistency of TEQ is high, ranging from α= 0.85 to 0.87, and its test-retest reliability is r=0.81 [4]. A good internal consistency (α=0.822) for TEQ was obtained in our study. The Brief COPE inventory is a self-report questionnaire that is used to assess coping mechanisms in reaction to a particular situation. It has 28 items and 14 subscales including self-distraction, active coping, posi- tive reframing, planning, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, venting, self-distraction, acceptance, self- blame, behavioral disengagement, humor, denial, religion, and substance use. Following the instructions, the participants rated the items on a scale from 1 to 4. The internal consistency for the 14 subscales ranges from 0.57 to 0.90 [4]. A good internal consistency (α=0.756) was obtained for this inventory in this study. The ProQoL scale has three subscales of BO, CF, and CS, and 30 items scored on a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). A high score show a high level. Cronbach’s alpha for these subscales is 0.88, 0.75, and 0.81, respectively [4]. An acceptable internal consistency (α=0.639) was obtained in this study.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed by in SPSS software, version 25 and were reported using mean and standard deviation. To examine the association between empathy, coping strategies, and ProQoL, Pearson correlation test was used. To examine the effect of demographic variables on these variables, categorical regression analysis was done by transforming demographic variables into dummy variables. The moderating role of work experience in the relationship between empathy and ProQoL was also tested.

Results

The correlation coefficients between the study variables as well as the mean scores of these variables are presented in Table 1.

There was a weak positive correlation among empathy, problem-focused coping strategies, and emotion-focused coping strategies (r=0.36 and 0.46; P=0.01). There was a moderate positive significant correlation between empathy and CS (r=0.47, P=0.01); a very weak positive significant correlation exists between empathy and BO (r=0.15, P=0.01); and a weak positive significant correlation between CS and problem-focused coping strategies (r=0.38, P=0.01). The relationship among problem-focused coping strategies, BO, and CF was weak and negative (r=-0.10 and 0.16, P=0.01). There was a weak positive significant correlation between emotion-focused coping strategies and CS (r=0.12, P=0.01). There was a positive and very weak correlation between BO and Avoidance coping strategies (r=0.6, P=0.05). The relationship between Avoidance coping strategies and CF was relatively weak and positive (r=0.15, P=0.05).

Categorical regression results

Table 2 shows the results for the effect of demographic variables (predictor variables) on study variables.

Model 1 shows the effect of demographic variables on empathy. The R2 value of 0.208 indicates that predictor variables explained about 20% of changes in empathy; F (10,69) =1.808. Gender and educational level had a significant impact on empathy (P<0.05), where females and those with PhD degree had more empathy. Age, years of work experience, marital status, and working hours per day had no significant impact on empathy. Model 2 shows the effect of demographic variables on coping strategies. The R2 value of 0.145 indicates that predictor variables explained about 14% of changes in coping strategies; F (10,69) =1.173. There was no significant impact of demographic variables on coping strategies compared to the reference group. Model 3 shows the effect of demographic variables on ProQoL. The R2 value of 0.234 indicates that the predictor variables explained about 23% of changes in ProQoL; F(10,69) =2.103. Age had a significant impact on ProQoL (P<0.05), where people aged 28-32 years of age had good ProQoL compared to the reference group. Gender, years of work experience, marital status, and working hours per day had no significant impact on ProQoL.

Moderation analysis results

Table 3 indicates the results assessing the moderating role of work experience in the relationship empathy and ProQoL.

In Model 1, the R² value of 0.79 indicated that the predictor explained 79% of variance in empathy; F (2,27)=3.303, P>0.05. The finding showed that (β=0.22, P<0.01) and work experience (β=-0.16, P<0.05) predicted ProQoL. In Model 2, R² value of 0.14 indicated that the predictor explained 14% variance in ProQoL; F (1.76) =0.02, P<0.001. The finding revealed that empathy (β=2.10, P<0.01) and work experience (β=-0.15, P>0.05) and empathy×work experience (β=0.256, P>0.01) predicted ProQoL. The ∆R² value of 0.06 revealed that work experience explained 6% of changes in empathy and ProQoL; ∆F (2, 77)=3.303, p<0.05. Finding show that work experience in years moderates the relationship between empathy and professional quality of life.

Simple slope analysis indicated that years of work experience acted as a buffer to increase the correlation between empathy and ProQoL (P<0.001) (Figure 3).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship among ProQoL, coping strategies, and empathy of clinical psychologists in Lahore, Pakistan. According to the results, there was a significant positive relationship between empathy, problem-focused coping strategies, and emotion-focused coping strategies. Problem-focused coping strategies include active managing, planning, and suppression of competing activities. Emotion-focused coping strategies include positive reframing, acceptance, religion, and humor. We found no significant relationship between empathy and avoidance coping strategies. These findings support the results of previous studies. Varadarajan et al. [19] found that perceived empathy, or one’s perceived capacity for empathy, negatively correlated with maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as behavioral disengagement). Sun et al. [20] reported that higher empathy was related to the usage of more adaptive coping strategies (active coping, positive reframing, planning, and acceptance), social support (instrumental and emotional support), and fewer maladaptive coping strategies (denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement, and self-blame).

Current study indicated a weak positive relationship between CS and problem-focused coping strategies. Previous research showed a positive relationship between problem-focused coping and job satisfaction. The amount of work, problem-focused coping, peer support, family and friend care, and CF all had an impact on job satisfaction [21]. There was a weak negative association between problem-focused coping strategies, BO, and CF. Other studies also showed a weak link between BO and problem-focused coping mechanisms. Higher scores in the instruments, which are a sign of successful use of inner resources for problem-solving, were seen as representing directives of job demands [22, 23]. In our study, there was a weak positive association between CS and emotion-focused coping strategies. The association between emotion-focused coping strategies, BO, and CF was not significant. These results are in contrast to the results of a previous research, which revealed that burnout might be caused by higher use of emotion-focused coping strategies and a lower problem-focused and avoidance coping strategies [24]. This discrepancy can be due to difference in the study population and various coping mechanisms used by clinical psychologists. There was a weak positive association between avoidance coping, BO, and CF. The previous study demonstrated that avoidance coping and CF had a significant relationship with each another. Better emotion-focused coping and lower problem-focused and avoidance coping may contribute to burnout [24]. Our study is consistent with previous studies focused on different strategies that involve problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping strategies. In Justin et al.’s [12] study on clinical psychologists, a significant positive relationship was observed among hardiness, control, commitment, active, positive reframing, planning, religious coping strategies, and CS; a significant negative relationship was seen between denial, and behavior disengagement coping strategies and CS; a significant positive relationship was observed between self-distraction, denial, and behavior disengagement coping strategies, CF, and burnout; and a significant negative relationship between hardiness, challenge, and commitment coping strategy, CF, and burnout [12]. In our study, empathy, CS, and BO had a moderate positive association with one another, but there was no significant association between CF and empathy. This is consistent with the results of Varadarajan, et al. [19], who found that the association between empathy, CF, and CS change significantly over time. Another research showed that empathy and adaptive coping strategies had a significant positive relationship with CS, and a significant negative relationship with burnout [25].

According to the present study, the relationship between empathy and ProQoL was moderated by clinical psychologists’ years of work experience. Various possible reasons can be behind this findings. Due to the pressure of the system, clinical psychologists are facing an increased stress and BO at workplace. Due to an increase in the number of patients and declining resources, they work long hours and feel less able to meet patient needs. Their compassion fatigue and an overall reduction in ProQoL can also be due to prolonged exposure to patients who are unwell, injured, suffering, or dying. These findings are consistent with a research in which pediatric nurses under the age of 40 and with 6–10 years of experience, showed a higher degree of burnout and a lower degree of compassion fulfillment [26].

To encourage healthy behaviors and enhance psychological health, a culture of health needs to be created. Good sleep hygiene, social support, mindfulness, reflective counseling, a manageable workload, and flexibility to manage family-work balance can promote a culture of health. Good sleep hygiene is a crucial factor in preventing burnout and boosting individual resilience [27]. According to social support studies, therapists who have solid meaningful relationships (both personal and professional) are less likely to burn out and be sad. Two emotional health interventions that have been shown to reduce burnout and foster resilience are mindfulness therapy and stress management technique [28].

Limitations and recommendations

The researcher faced some limitations in the present study. Since the study design was cross-sectional, causal relathionships could not be determined. The data was only collected from one city and participants were mostly females, which reduce the generalizability of results. Moreover, this research used self-report tools that may contain biases in responses; therefore, other measures such as interviews with colleagues and family members can be used in future studies.

The results of this study suggest that awareness is crucial for stress management and reduction of compassion fatigue. Hence, experimental studies can be done to develop rules that can help prevent burnout and compassion fatigue in healthcare providers. Hence, mediation and educational programs can be done to improve knowledge of adaptive problem-focused coping in clinical psychologists and even in the administrative staff of hospitals.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study objectives were explained to them. They were free to leave the study at any time and were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of the second author in Clinical Psychology. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, and initial draft preparation: Areeba Ikram; Methodology, writing, editing & review: Areeba Ikram and Sana Anwar Lashari; Funding Acquisition: Sana Anwar Lashari and Tahira Anwar Lashari; Supervision: Sana Anwar Lashari.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Refrences

- ] Huang L, Thai J, Zhong Y, Peng H, Koran J, Zhao XD. The positive association between empathy and self-esteem in Chinese medical students: A multi-institutional study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019; 10:1921. [Link]

- Lashari TA, Lashari SA, Lashari SA, Nawaz S, Waheed Z, Fatima T. Job embeddedness: Factors and barriers of persons with disabilities. Journal of Technical Education and Training. 2022; 14(3):153-65. [DOI:10.30880/jtet.2022.14.03.014]

- Taché J, Selye H. On stress and coping mechanisms. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1985; 7(1-4):3-24. [DOI:10.3109/01612848509009447] [PMID]

- Stamm B. The concise manual for the professional quality of life scale. Pocat ello: ProQoL.org; 2010. [Link]

- El-Shafei DA, Abdelsalam AE, Hammam RAM, Elgohary H. Professional quality of life, wellness education, and coping strategies among emergency physicians. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 2018; 25(9):9040-50. [DOI:10.1007/s11356-018-1240-y] [PMID]

- Laverdière O, Ogrodniczuk JS, Kealy D. Clinicians' empathy and professional quality of life. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2019; 207(2):49-52. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000927] [PMID]

- Thomas JT, Otis MD. Intrapsychic correlates of professional quality of life: Mindfulness, empathy, and emotional separation. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2010; 1(2):83-98. [DOI:10.5243/jsswr.2010.7]

- Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists' chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002; 58(11):1433-41. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.10090] [PMID]

- Thompson I, Amatea E, Thompson E. Personal and contextual predictors of mental health counselors’ compassion fatigue and burnout. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2014; 36(1):58-77. [DOI:10.17744/mehc.36.1.p61m73373m4617r3]

- Ansari K, Lodhia L. A comparative study of the professional quality of life between trainees in the field of medicine and mental health. Pakistan Journal of Psychology. 2013; 44(1):37-50. [Link]

- Raynor D, Hicks R. Empathy and coping as predictors of professional quality of life in Australian registered migration agents. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law. 2018; 26(4):530-40. [DOI:10.1080/13218719.2018.1507846] [PMID]

- Justin M, Haroon Z, Asad Khan M. Hardiness, coping strategies and professional quality of life among practicing clinical psychologists. Academic Journal of Social Sciences. 2023; 7(1):124-36 [DOI:10.54692/ajss.2023.07011904]

- Batool N. Mental health issues in Pakistan [Internet]. 2023. [Updated 2023 November]. Available from [Link]

- Shaheen S, Sadiq M. Distress and professional quality of life among clinical psychologists and psychiatrists. The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2019; 7(1):33. [Link]

- Tay S, Alcock K, Scior K. Mental health problems among clinical psychologists: Stigma and its impact on disclosure and help-seeking. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018; 74(9):1545-55. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22614] [PMID]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007; 42(1):185-227.[DOI:10.1080/00273170701341316]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford publications; 2017. [Link]

- Heath C, Sommerfield A, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anesthesia. 2020; 75(10):1364-71. [PMID]

- Varadarajan A, Rani J. Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction and coping between male and female intensive care unit nurses. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021; 12(1):49-52. [Link]

- Sun R, Vuillier L, Hui BP, Kogan A. Caring helps: Trait empathy is related to better-coping strategies and differs in the poor versus the rich. Plos One. 2019; 14(3):e0213142. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0213142] [PMID]

- Reilly SE, Soulliard ZA, McCuddy WT, Mahoney JJ 3rd. Frequency and perceived effectiveness of mental health providers' coping strategies during COVID-19. Current Psychology. 2021; 40(11):5753-62. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-021-01683-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Iftikhar S, Farooq V, Muslim A, Lashari TA, Khan I, Lashari SA, et al. Examining the need for an integrated framework: exploring the intersection of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) in entrepreneurship competency development, STEAM education, and gamification. Journal of Xi’an Shiyou University, Natural Science Edition. 19(6):1257-67. [Link]

- Derakhshanrad SA, Piven E, Zeynalzadeh Ghoochani B. The relationships between problem-solving, creativity, and job burnout in Iranian occupational therapists. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2019; 33(4):365-80. [DOI:10.1080/07380577.2019.1639098] [PMID]

- Meyerson J, Gelkopf M, Eli I, Uziel N. Stress coping strategies, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction amongst israeli dentists: A cross-sectional study. International Dental Journal. 2022; 72(4):476-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.identj.2021.09.006] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cao X, Li J, Gong S. The relationships of both transition shock, empathy, resilience and coping strategies with professional quality of life in newly graduated nurses. BMC Nursing. 2021; 20(1):65. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-021-00589-0] [PMID]

- Berger J, Polivka B, Smoot EA, Owens H. Compassion fatigue in pediatric nurses. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2015; 30(6):e11-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2015.02.005] [PMID]

- Mujtaba A, Lashari TA, Lashari SA, Khattak MA, Mujtaba K, Mujtaba M. Determining the effect of social and academic support on STEM confidence and learning environment among female engineering students in Pakistan. Journal of Technical Education and Training. 2023; 15(2):50-60. [DOI:10.30880/jtet.2023.15.02.005]

- Healthwire. Pakistan (LU).101 Top certified clinical psychologists in Lahore [Internet]. 2020.

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2023/04/11 | Accepted: 2023/05/30 | Published: 2023/07/1

Received: 2023/04/11 | Accepted: 2023/05/30 | Published: 2023/07/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |