Sun, Feb 22, 2026

| فارسی

Volume 28, Issue 4 (Winter 2023)

IJPCP 2023, 28(4): 460-477 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Roozbahani S, Dolatian M, Mahmoodi Z, Zandifar A, Alavi Majd H, Nasiri S. Predictors of Maternal Blouse in the Postpartum Period Based on Social Determinants of Health of the World Health Organization Model: A Path Analysis. IJPCP 2023; 28 (4) :460-477

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3822-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3822-en.html

Sahar Roozbahani1

, Mahrokh Dolatian2

, Mahrokh Dolatian2

, Zohreh Mahmoodi3

, Zohreh Mahmoodi3

, Atefeh Zandifar3

, Atefeh Zandifar3

, Hamid Alavi Majd4

, Hamid Alavi Majd4

, Saeideh Nasiri5

, Saeideh Nasiri5

, Mahrokh Dolatian2

, Mahrokh Dolatian2

, Zohreh Mahmoodi3

, Zohreh Mahmoodi3

, Atefeh Zandifar3

, Atefeh Zandifar3

, Hamid Alavi Majd4

, Hamid Alavi Majd4

, Saeideh Nasiri5

, Saeideh Nasiri5

1- Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,mhdolatian@gmail.com

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

2- Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 6646 kb]

(1062 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2936 Views)

Full-Text: (1669 Views)

Introduction

The birth of a new child and adapting to the postpartum period are stressful for mothers and they face many challenges. The challenges faced by mothers in the postpartum period can cause mental disorders, such as, anxiety, depression, or blouse after childbirth. The maternal blouse is the mildest form of mood disorder in the postpartum period. The prevalence rate of this disorder is between 13.7% and 76%. Symptoms of postpartum blouse include insomnia, mood swings, the tendency to cry, exhaustion, irritability, and emotional instability. Although the exact cause of maternal blouse is not known, several factors, such as hormonal changes, socio-cultural and socioeconomic status, relationship conflicts, domestic violence, male gender preference, fatigue due to insomnia, anxiety about not being able to take care of the baby, fear of decreasing the attractiveness after childbirth, etc., are related to this disorder. In recent years, measures in the social determinants of health based on the World Health Organization (WHO) model, have been considered a priority for preventing mental disorders. In this model, there are two groups of structural and intermediate determinants. Structural factors include education, employment, income, gender, and ethnicity, and intermediate factors include material conditions, psychosocial, behavioral, and biological factors, and health systems. This study was conducted to determine the predictors of maternal blouse in the postpartum period based on social determinants of health of (WHO).

Methods

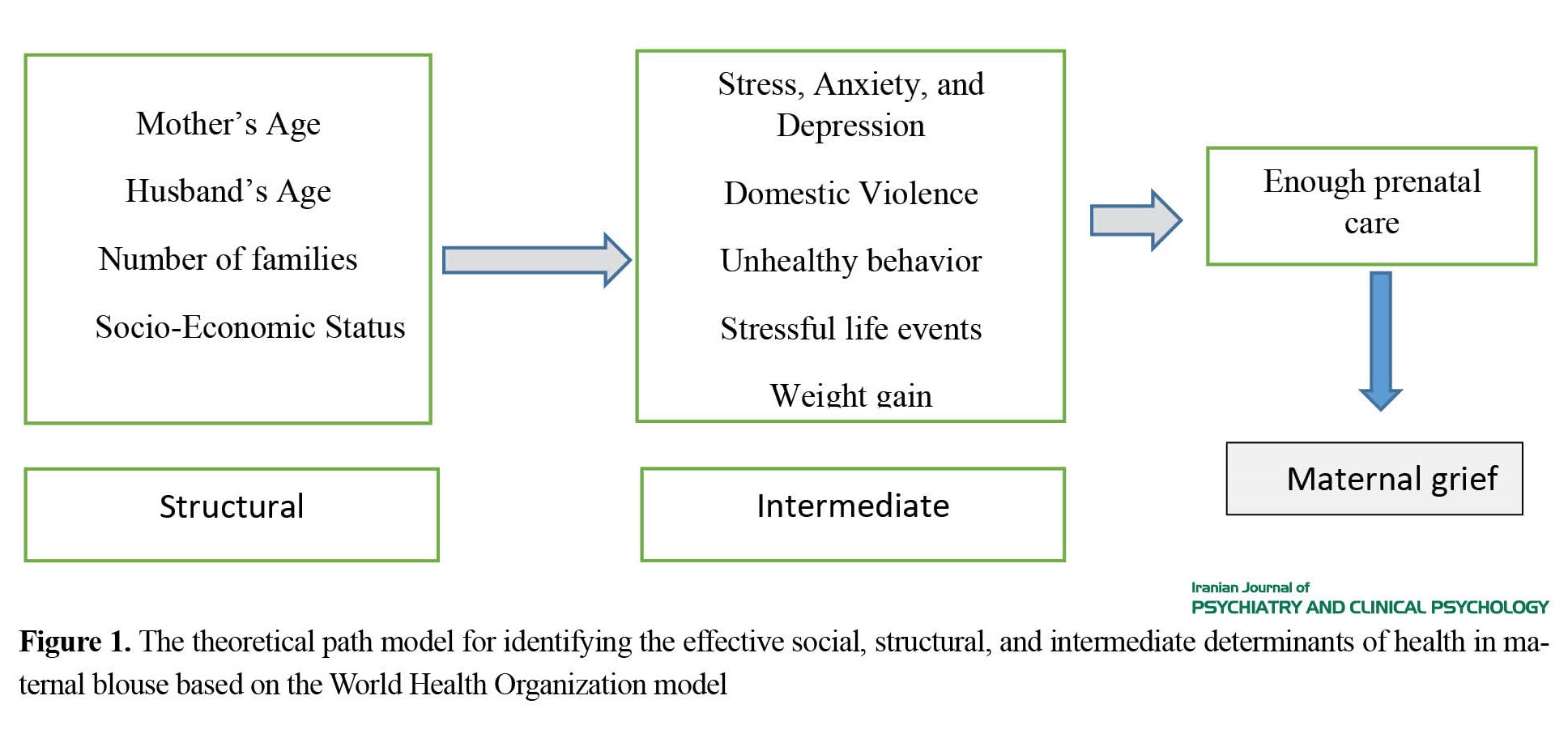

This study is a prospective quantitative study on pregnant women referred to selected hospitals in Tehran to determine the structural and intermediate factors affecting maternal blouse. The sampling method was multi-stage. Participants were followed up until delivery, and information about delivery and pregnancy outcomes was collected to determine the incidence of maternal blouse. In this study, in order to determine the factors related to maternal grief, a conceptual model was first determined through a review of comprehensive texts, and then the final model was confirmed by holding meetings with a group of experts and researchers in the field of reproductive health and social determinants affecting health or mental health (Figure 1).

The birth of a new child and adapting to the postpartum period are stressful for mothers and they face many challenges. The challenges faced by mothers in the postpartum period can cause mental disorders, such as, anxiety, depression, or blouse after childbirth. The maternal blouse is the mildest form of mood disorder in the postpartum period. The prevalence rate of this disorder is between 13.7% and 76%. Symptoms of postpartum blouse include insomnia, mood swings, the tendency to cry, exhaustion, irritability, and emotional instability. Although the exact cause of maternal blouse is not known, several factors, such as hormonal changes, socio-cultural and socioeconomic status, relationship conflicts, domestic violence, male gender preference, fatigue due to insomnia, anxiety about not being able to take care of the baby, fear of decreasing the attractiveness after childbirth, etc., are related to this disorder. In recent years, measures in the social determinants of health based on the World Health Organization (WHO) model, have been considered a priority for preventing mental disorders. In this model, there are two groups of structural and intermediate determinants. Structural factors include education, employment, income, gender, and ethnicity, and intermediate factors include material conditions, psychosocial, behavioral, and biological factors, and health systems. This study was conducted to determine the predictors of maternal blouse in the postpartum period based on social determinants of health of (WHO).

Methods

This study is a prospective quantitative study on pregnant women referred to selected hospitals in Tehran to determine the structural and intermediate factors affecting maternal blouse. The sampling method was multi-stage. Participants were followed up until delivery, and information about delivery and pregnancy outcomes was collected to determine the incidence of maternal blouse. In this study, in order to determine the factors related to maternal grief, a conceptual model was first determined through a review of comprehensive texts, and then the final model was confirmed by holding meetings with a group of experts and researchers in the field of reproductive health and social determinants affecting health or mental health (Figure 1).

Path analysis is an analytical and extensive method of regression analysis that is used to test causal models and requires setting a model in the form of a diagram. The number of samples was considered to be 449 people. Questionnaires were used for data collection, including Demographic and Midwifery Characteristics Questionnaire, Socio-Economic Status Questionnaire (SES), Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), Domestic Violence Questionnaire (DVQ), Unhealthy Behavior Questionnaire, and Stein Maternal Blouse Questionnaire. Collected data were analyzed using SPSS (version 26, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and LISREL (version 8.8, Scientific Software International, IL, USA) software. A significant level of less than 0.05 was considered. Path analysis was used to determine the most important determinants of the maternal blouse and the direct and indirect effects of various variables and test the proposed conceptual model.

Results

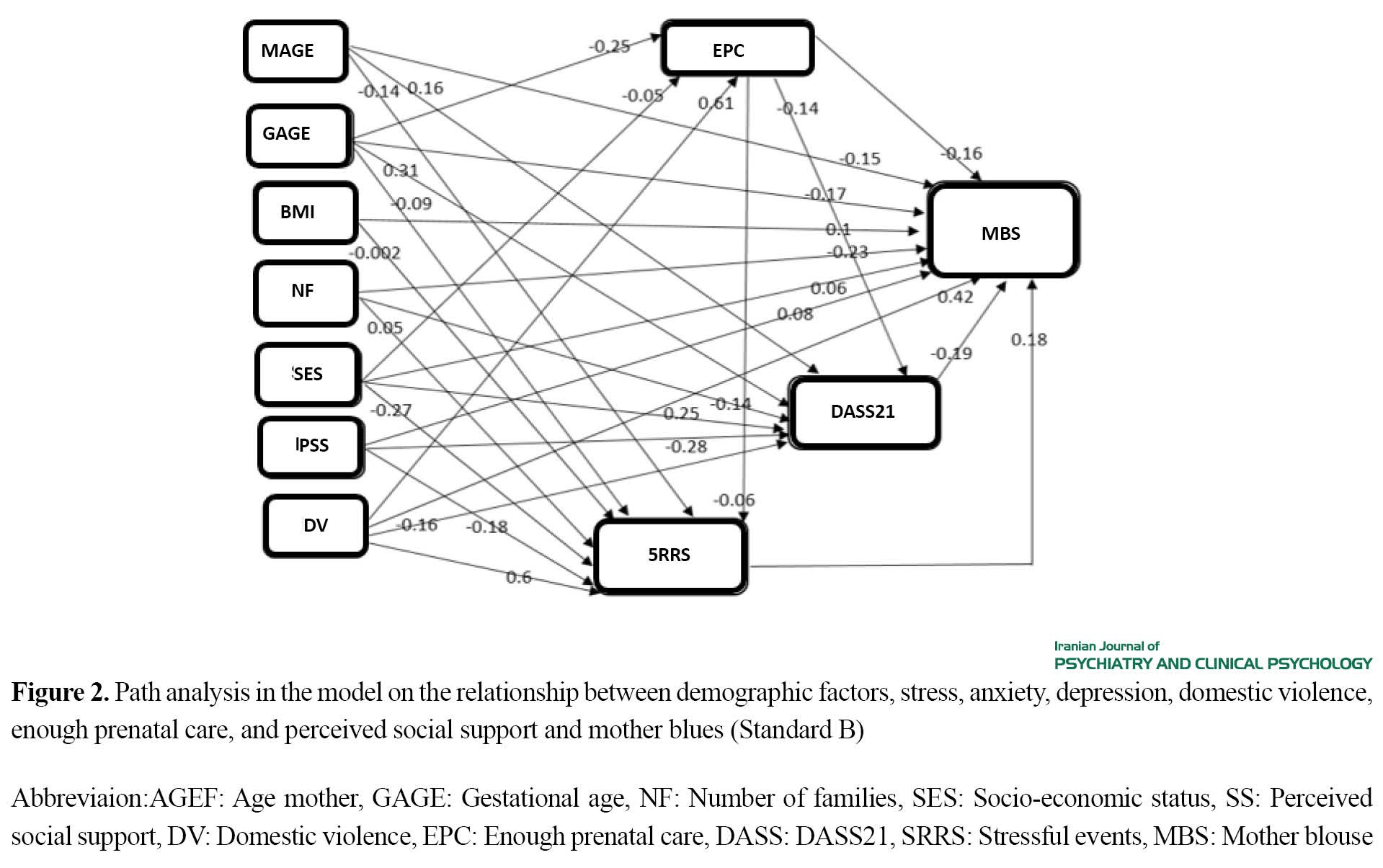

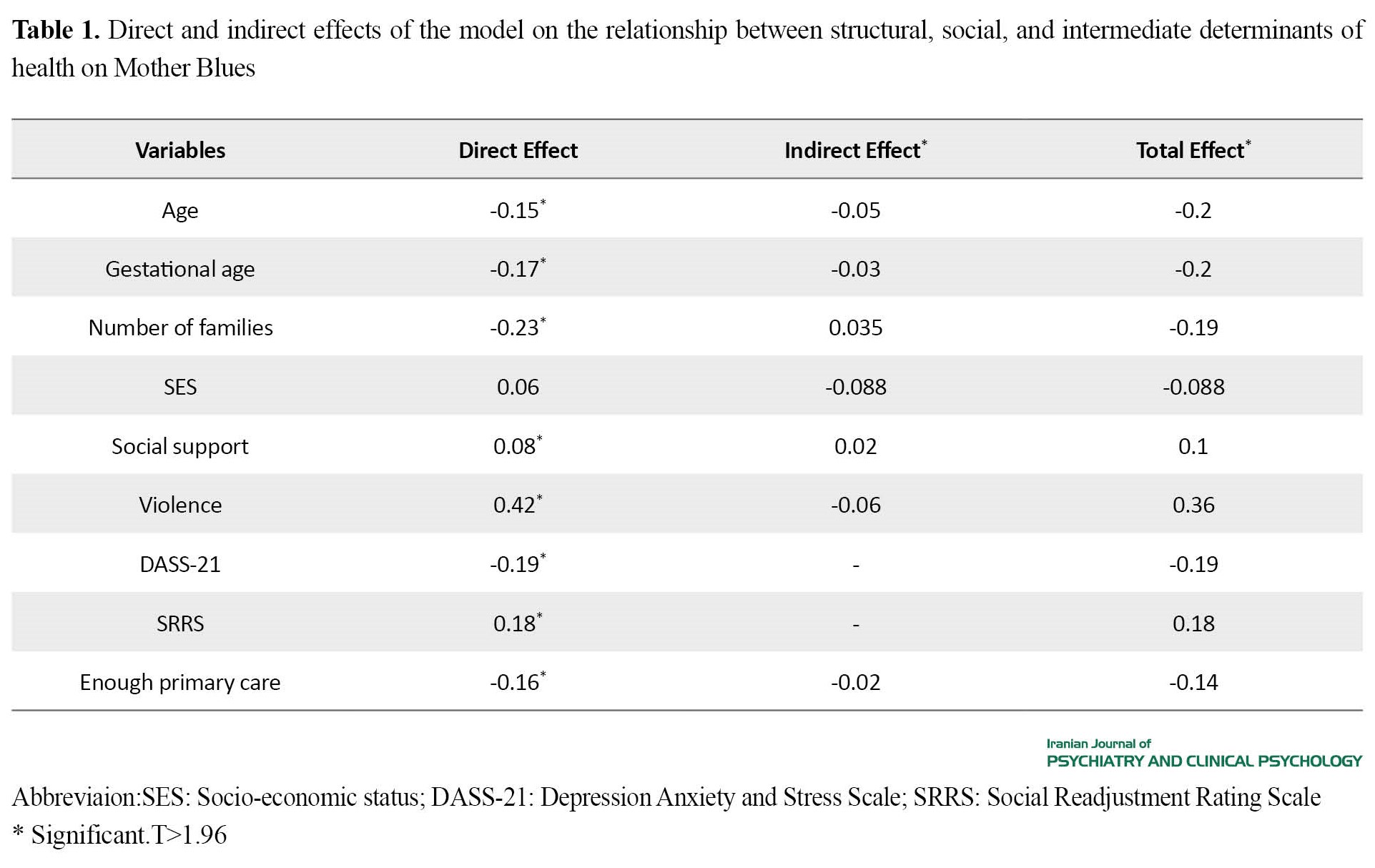

The information of 449 pregnant women participating in the study was examined. According to the findings, the average age of women was 26.96±4.46 years and that of their husbands was 32.17±5.6 years, their stress score was 4.2±5.9, anxiety was 3.1±5.3, and depression was 3.1±5.6. Based on the results of the path analysis, among the variables that were related to sadness, socio-economic status had the most negative effect on sadness in the indirect path (one-path test), and DASS21 had the most negative effect in the direct path (B=-0.19) and Incidents had the most positive effect (B=0.18) with sadness. Among the variables that were related to sadness (two-path test), violence had the most positive effect (B=0.36), and a woman’s age, gestational age, and the number of family members (B=-0.2) had the most negative effect on sadness (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Results

The information of 449 pregnant women participating in the study was examined. According to the findings, the average age of women was 26.96±4.46 years and that of their husbands was 32.17±5.6 years, their stress score was 4.2±5.9, anxiety was 3.1±5.3, and depression was 3.1±5.6. Based on the results of the path analysis, among the variables that were related to sadness, socio-economic status had the most negative effect on sadness in the indirect path (one-path test), and DASS21 had the most negative effect in the direct path (B=-0.19) and Incidents had the most positive effect (B=0.18) with sadness. Among the variables that were related to sadness (two-path test), violence had the most positive effect (B=0.36), and a woman’s age, gestational age, and the number of family members (B=-0.2) had the most negative effect on sadness (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Discussion

The path analysis results demonstrated that among the variables related to maternal blouse(one-path test), in the indirect path analysis, socio-economic status had the most negative effect on the maternal blouse and also in the direct path analysis, DASS21 showed the most negative effect on the maternal blouse (B=-0.19) and the unfortunate event had the most positive effect (B=0.18). Violence had the most positive effect on maternal blouse in the two-path test (B=0). Evidence shows that risk factors for postpartum depression include poor social support, marital discord, domestic violence, economic insecurity, and poor maternal care during childhood. Socioeconomic status (occupation, education, and income) is a structural social factor determining health. This factor has a known effect on the occurrence of postpartum mood disorders. Okunola et al. [30] showed that women with higher education get lower scores on the Edinburgh Questionnaire. Stress, anxiety, and depression only directly affect the occurrence of postpartum blouse, although as intermediary determinants, some factors can affect them. Neurophysiological changes in the postpartum period increase vulnerability to depression in stressful situations. This study found that social support can, directly and indirectly, affect the occurrence of postpartum blouse. Badr et al. [44] found that women who received more social support during the prenatal and postpartum stages did not have postpartum depression. Social support can affect the stressful phenomena and stress and anxiety and depression of women and increase the incidence of postpartum blouse. In the postpartum period, when women’s stressful situations increase, adequate support can positively affect a person’s mental and physical health. Violence directly affects the occurrence of blouse; it can also increase stress, anxiety, depression, and the amount of blouse after childbirth. Women of reproductive age, especially during pregnancy and after childbirth, are vulnerable to mental health problems due to domestic violence. According to the results, the proposed model can be recommended for the planning of policymakers and healthcare workers to improve women’s mental health in the postpartum period and provide a solution to eliminating risk factors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical considerations were considered in this study. All participants were allowed to leave the study at any time and were assured of the confidentiality of their information. This study received ethical approval from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1400.595).

Funding

This study was funded by the Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center and the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors contributions

The authors contributed equally to preparing this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants cooperated in this study and the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and the Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center.

References

The path analysis results demonstrated that among the variables related to maternal blouse(one-path test), in the indirect path analysis, socio-economic status had the most negative effect on the maternal blouse and also in the direct path analysis, DASS21 showed the most negative effect on the maternal blouse (B=-0.19) and the unfortunate event had the most positive effect (B=0.18). Violence had the most positive effect on maternal blouse in the two-path test (B=0). Evidence shows that risk factors for postpartum depression include poor social support, marital discord, domestic violence, economic insecurity, and poor maternal care during childhood. Socioeconomic status (occupation, education, and income) is a structural social factor determining health. This factor has a known effect on the occurrence of postpartum mood disorders. Okunola et al. [30] showed that women with higher education get lower scores on the Edinburgh Questionnaire. Stress, anxiety, and depression only directly affect the occurrence of postpartum blouse, although as intermediary determinants, some factors can affect them. Neurophysiological changes in the postpartum period increase vulnerability to depression in stressful situations. This study found that social support can, directly and indirectly, affect the occurrence of postpartum blouse. Badr et al. [44] found that women who received more social support during the prenatal and postpartum stages did not have postpartum depression. Social support can affect the stressful phenomena and stress and anxiety and depression of women and increase the incidence of postpartum blouse. In the postpartum period, when women’s stressful situations increase, adequate support can positively affect a person’s mental and physical health. Violence directly affects the occurrence of blouse; it can also increase stress, anxiety, depression, and the amount of blouse after childbirth. Women of reproductive age, especially during pregnancy and after childbirth, are vulnerable to mental health problems due to domestic violence. According to the results, the proposed model can be recommended for the planning of policymakers and healthcare workers to improve women’s mental health in the postpartum period and provide a solution to eliminating risk factors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical considerations were considered in this study. All participants were allowed to leave the study at any time and were assured of the confidentiality of their information. This study received ethical approval from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1400.595).

Funding

This study was funded by the Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center and the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors contributions

The authors contributed equally to preparing this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants cooperated in this study and the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and the Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center.

References

- Mahmoodi Z, Karimlou M, Sajjadi H, Dejman M, Vameghi M. Development of mother's lifestyle scale during pregnancy with an approach to social determinants of health. Global Journal of Health Science. 2013; 5(3):208-19. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v5n3p208] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sobhani E, Babakhani N, Alebouyeh MR. [The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the depression, anxiety, stress, and pain perception in females with obstructed labour-induced chronic low back pain (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2019; 25(3):266-77. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.25.3.266]

- Lotfi M, Amin M, Shiasy Y. [Comparing interpersonal and intrapersonal emotion regulation models in explaining depression and anxiety symptoms in college students (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2021; 27(3):288-301. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.27.2.2359.2]

- Chandra PS, Herrman H, Fisher J, Kastrup M, Niaz U, Rondon MB, et al. Contemporary topics in women mental health. Hoboken: John Wiley &sons; 2009. [Link]

- Ntaouti E, Gonidakis F, Nikaina E, Varelas D, Creatas G, Chrousos G, et al. Maternity blues: Risk factors in greek population and validity of Greek version of Kennerly and Gath blues questionnaire. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2018; 28:1-10. [DOI:10.1080/14767058.2018.1548594] [PMID]

- Rezaie-Keikhaie K, Arbabshastan ME, Rafiemanesh H, Amirshahi M, Ostadkelayeh SM, Arbabisarjou A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of the maternity blues in the postpartum period. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2020; 49(2):127-36. [DOI:10.1016/j.jogn.2020.01.001] [PMID]

- Bagherzadeh R, Zahmatkeshan N, Moatamed N, Khorramroudi R, Ganjoo M. [Prevalence of maternal blues, postpartum depression and their correlation with premenstrual syndrome in women refferred to health centers affiliated to Bushehr University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2009; 12(3):9-15. [DOI:10.22038/IJOGI.2009.5883]

- Moslemi L. Prevalence and several effective factors on maternity blues. Healthmed. 2012; 6(7): 2299-303. [Link]

- Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, et al. Williams obstetrics. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2014. [Link]

- Alvarado-Esquivel C, Sifuentes-Alvarez A, Salas-Martinez C. Validation of the edinburgh postpartum depression scale in a population of adult pregnant women in Mexico. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research. 2014; 6(5):374-8. [DOI:10.14740/jocmr1883w] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dolatian M, Maziar P, Alavimajd H, Yazdjerdi M. The relationship between mode of delivery and postpartum depression. Journal of Reproduction & Infertility. 2006; 7(3):260-8. [Link]

- Smith MV, Shao L, Howell H, Lin H, Yonkers KA. Perinatal depression and birth outcomes in a healthy start project. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011; 15(3):401-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10995-010-0595-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fellmeth G, Fazel M, Plugge E. Migration and perinatal mental health in women from low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017; 124(5):742-52. [DOI:10.1111/1471-0528.14184] [PMID]

- Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M. Social determinants of mental health. International Review of Psychiatry. 2014; 26(4):392-407. [DOI:10.3109/09540261.2014.928270] [PMID]

- Streiner DL. Finding our way: An introduction to path analysis. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2005; 50(2):115-22. [DOI:10.1177/070674370505000207] [PMID]

- Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research. Philadelphia: Lippincott williams & wilkins; 2005. [Link]

- Loehlin JC, Beaujean AA. Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural equation analysis. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis; 2016. [Link]

- Ghodratnama A, Heidarinejad S, Davoodi I. [The relationship between socio-economic status and the rate of physical activity in Shahid Chamran University Students of Ahwaz (Persian)]. Sport Management Journal. 2013; 5(16):5-20. [DOI:10.22059/jsm.2013.30410]

- Eslami A, Mahmoudi A, Khabiri M, Najafiyan Razavi SM. [The role of socioeconomic conditions in the citizens’ motivation for participating in public sports (Persian)]. Applied Research in Sport Management. 2014; 2(3):89-104. [Link]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995; 33(3):335-43.[DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U] [PMID]

- Sahebi A, Asghari MJ, Salari RS. [Validation of depression anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21) for an Iranian population (Persian)]. Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2005; 1(4):36-54. [Link]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988; 52(1):30-41. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2]

- Bagherian-Sararoudi R, Hajian A, Ehsan HB, Sarafraz MR, Zimet GD. Psychometric properties of the persian version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in iran. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013; 4(11):1277-81. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Noone PA. The holmes-rahe stress inventory. Occupational Medicine. 2017; 67(7):581-2. [DOI:10.1093/occmed/kqx099] [PMID]

- Heydari A, Namjoosangari Z. [Comparison of emotional disability, attachment and stress between married male and female employees of Ahvaz National Drilling Company (Persian)]. New Findings in Psychology. 2011; 6(20):21-40. [Link]

- Hajian S, Vakilian K, Mirzaii Najm-abadi K, Hajian P, Jalalian M. Violence against women by their intimate partners in Shahroud in northeastern region of Iran. Global Journal of Health Science. 2014; 6(3):117-30. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v6n3p117] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Stein GS. The pattern of mental change and body weight change in the first post-partum week. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1980; 24(3-4):165-71. [DOI:10.1016/0022-3999(80)90038-0] [PMID]

- Plichta SB, Kelvin E. Munro’s statistical methods for health care research. Amsterdam: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2013. [Link]

- Miller ML, Kroska EB, Grekin R. Immediate postpartum mood assessment and postpartum depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017; 207:69-75. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.023] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Okunola TO, Awoleke JO, Olofinbiyi B, Rosiji B, Omoya S, Olubiyi AO. Postnatal blues: A mirage or reality. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2021; 6:100237. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100237]

- Gerli S, Fraternale F, Lucarini E, Chiaraluce S, Tortorella A, Bini V, et al. Obstetric and psychosocial risk factors associated with maternity blues. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021; 34(8):1227-32. [DOI:10.1080/14767058.2019.1630818] [PMID]

- Bałkowiec-Iskra E, Niewada M. [Postpartum depression - diagnosis and treatment (Polish)]. Przewodnik Lekarza/Guide for GPs. 2002; 5(11):104-10. [Link]

- Baston H, Hall, J. Midwifery essentials: Labour. London: Elsevier; 2017. [Link]

- Manjunath NG, Venkatesh G, Rajanna. Postpartum blue is common in socially and economically insecure mothers. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2011; 36(3):231-3 [DOI:10.4103/0970-0218.86527] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Reichman NE, Corman H, Noonan K, Schwartz-Soicher O. Effects of prenatal care on maternal postpartum behaviors. Review of Economics of the Household. 2010; 8(2):171-97. [DOI:10.1007/s11150-009-9074-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wang D, Li YL, Qiu D, Xiao SY. Factors influencing paternal postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021; 293:51-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.088] [PMID]

- van der Zee-van den Berg AI, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Reijneveld SA. Postpartum depression and anxiety: A community-based study on risk factors before, during and after pregnancy. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021; 286:158-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.062] [PMID]

- Wei DM, Au Yeung SL, He JR, Xiao WQ, Lu JH, Tu S, et al. The role of social support in family socio-economic disparities in depressive symptoms during early pregnancy: Evidence from a Chinese birth cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018; 238:418-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.014] [PMID]

- Wszołek K, Żak E, Żurawska J, Olszewska J, Pięta B, Bojar I. Influence of socio-economic factors on emotional changes during the postnatal period. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2018; 25(1):41-5. [DOI:10.26444/aaem/74486] [PMID]

- Cheng B, Roberts N, Zhou Y, Wang X, Li Y, Chen Y, et al. Social support mediates the influence of cerebellum functional connectivity strength on postpartum depression and postpartum depression with anxiety. Translational Psychiatry. 2022; 12(1):54. [PMID]

- Reck C, Stehle E, Reinig K, Mundt C. Maternity blues as a predictor of DSM-IV depression and anxiety disorders in the first three months postpartum. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009; 113(1-2):77-87. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.003] [PMID]

- Murata A, Nadaoka T, Morioka Y, Oiji A, Saito H. Prevalence and background factors of maternity blues. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 1998; 46(2):99-104. [DOI:10.1159/000010011] [PMID]

- Hergüner S. [Association of delivery type with postpartum depression, perceived social support and maternal attachment (Turkish)]. Düşünen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences. 2014; 27:15-20. [DOI:10.5350/DAJPN2014270102]

- Badr LK, Abdallah B, Mahmoud A. Precursors of preterm birth: Comparison of three ethnic groups in the middle East and the United States. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2005; 34(4):444-52. [DOI:10.1177/0884217505276303] [PMID]

- Aytac SH, Yazici S. The effect of social support on pregnancy and postpartum depression. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2020; 13(1):746. [Link]

- Mermer G, Bilge A, Yücel U, Çeber E. Evaluation of perceived social support levels in pregnancy and postpartum periods. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2010; 1(2):71-6. [Link]

- Okanli A, Tortumluoglu G, Kirpinar İ. [The relationship between pregnant women perceived social support from family and problem solving skill (Turkish)]. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2003; 4(2):98. [Link]

- Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Kohn R. Intimate partner violence and long-term psychosocial functioning in a national sample of American women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006 Feb;21(2):262-75.[DOI:10.1177/0886260505282564] [PMID]

- Nisar A, Yin J, Waqas A, Bai X, Wang D, Rahman A, et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020; 277:1022-37. [PMID]

- Bahati C, Izabayo J, Niyonsenga J, Sezibera V, Mutesa L. Intimate partner violence as a predictor of antenatal care services utilization in Rwanda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2021 Nov 8;21(1):754. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-021-04230-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Abbaszadeh A, Pouryazdanpanah F, Safizadeh H, Nakhea N. Violence during pregnancy and postpartum depression. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2011;27 (1):177-81. [Link]

- Baba Pour J, Sattar Zadeh N, Khodaei R. [Physical violence against pregnant women: risk factors and its relation to some pregnancy outcomes in women referring to Tabriz educational hospitals in 1386 (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal. 2007; 5(4):29-44. [Link]

- Baheri B, Ziaie M, Mohammadi SZ. [Frequency of domestic violence in women with adverse pregnancy outcomes (Karaj 2007-2008) (Persian)]. Avicenna Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Care. 201; 20(1):31-41. [Link]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2022/12/20 | Accepted: 2023/03/6 | Published: 2023/01/1

Received: 2022/12/20 | Accepted: 2023/03/6 | Published: 2023/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |