Mon, Dec 8, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 28, Issue 4 (Winter 2023)

IJPCP 2023, 28(4): 508-519 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Asgharipour N, Nouri Siahdasht N, Javdani Asl A, Hajebi Khaniki S. Investigating the Quality of Professional life of Mashhad Psychotherapists in 2022. IJPCP 2023; 28 (4) :508-519

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3804-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3804-en.html

1- Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Ibn-e-Sina Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. ,nafisenouri192@gmail.com

3- Department of General Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

4- Student Research Committee, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. ,

3- Department of General Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

4- Student Research Committee, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 4820 kb]

(921 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2492 Views)

Full-Text: (883 Views)

Introduction

The daily activities of psychotherapists require close cooperation with people who are in mental distress and suffer from various mental disorders. Psychotherapy is based on communication and emotional capacities that are used during therapy sessions and can cause emotional traumas to therapists and affect their professional quality of life [1]. Three main factors, including job burnout, fatigue from compassion, and secondary traumatic stress injury, can influence the quality of life of therapists.

Job burnout is an important issue among psychologists and psychotherapists that affects 20-67% of working psychotherapists [2, 3]. The level of emotional exhaustion in working psychologists was reported higher than in other health and treatment staff [4].

Fatigue from compassion is defined as frustration and exhaustion from compassion in patient care, where the caregiver feels frustrated due to observing the devastating injury and illness of patients [3]. The symptoms are presented as physical exhaustion and appear in the form of physical fatigue while other symptoms of this condition may range from symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress syndrome to nervousness and anxiety, decreased self-confidence, and physical symptoms, such as headache and dizziness [5, 6].

Secondary traumatic stress injury is defined as indirect exposure to a traumatic event [7]. The symptoms are similar to the symptoms of post-traumatic stress along with positive changes in self-understanding, interpersonal relationships with others, and philosophy of life [8].

The factors influencing professional quality of life in psychotherapists have not been well investigated and there is no consensus in this regard. Considering that similar studies have not been conducted in Iran, especially in Mashhad the second largest city in Iran, the purpose of this study was to investigate the quality of professional life of psychotherapists.

Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on psychologists and psychiatrists working in Mashhad City in 2022 based on convenience sampling methods. The inclusion criteria were psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors working in Mashhad, and willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were incomplete questionnaires, the presence of a specific pattern in answering questions, and choosing two or more choices for more than five questions.

Data were collected using a questionnaire comprised of demographic information (age and gender), job information (type of employment and work approach), and Stam’s quality of professional life questionnaire (2009). The questionnaire has 30 items and three components, including satisfaction from compassion, secondary traumatic stress, and job burnout (ten items for each component).

Participants were informed about the study through email and social media platforms. Psychotherapists who were working in Mashhad at the time of conducting the research (based on self-report) completed the questionnaires through the link sent in the invitation message.

Results

A total of 184 participants (91, 49.5% men and 93, 50.5% women) were studied. The average age of all subjects was 37.4±7.6 years. There was no significant difference in terms of age between genders. Also, 46.7% (86 people) were contractually employed, 35.9% (66 people) were officially employed, and 17.4% (32 people) were on duty. The average working experience of the participants was 6.5±6.6 years.

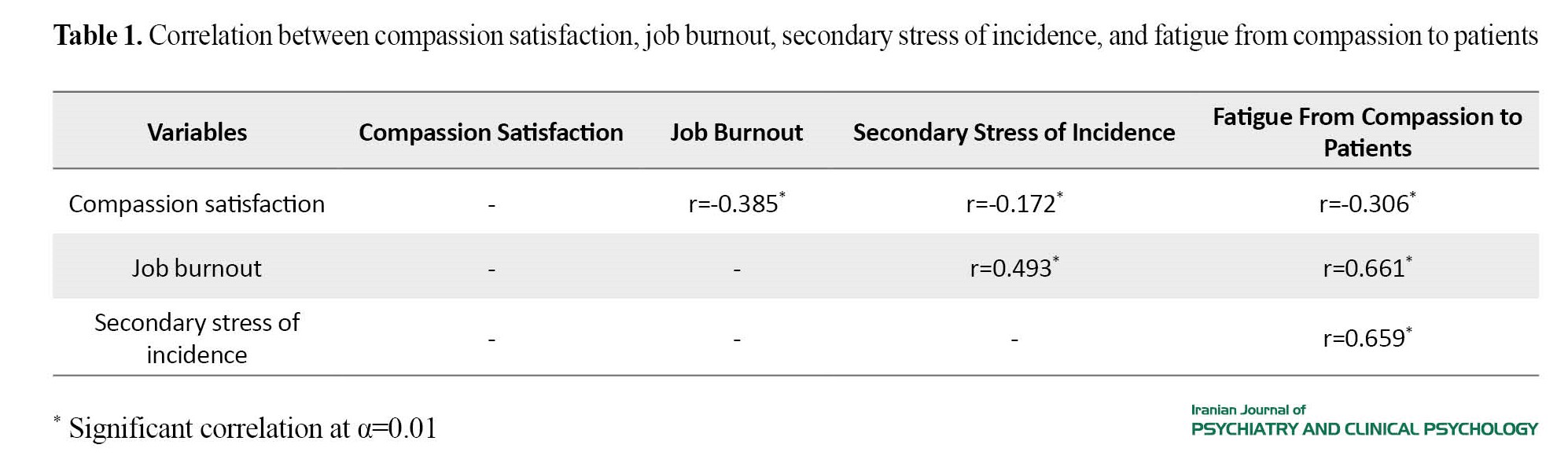

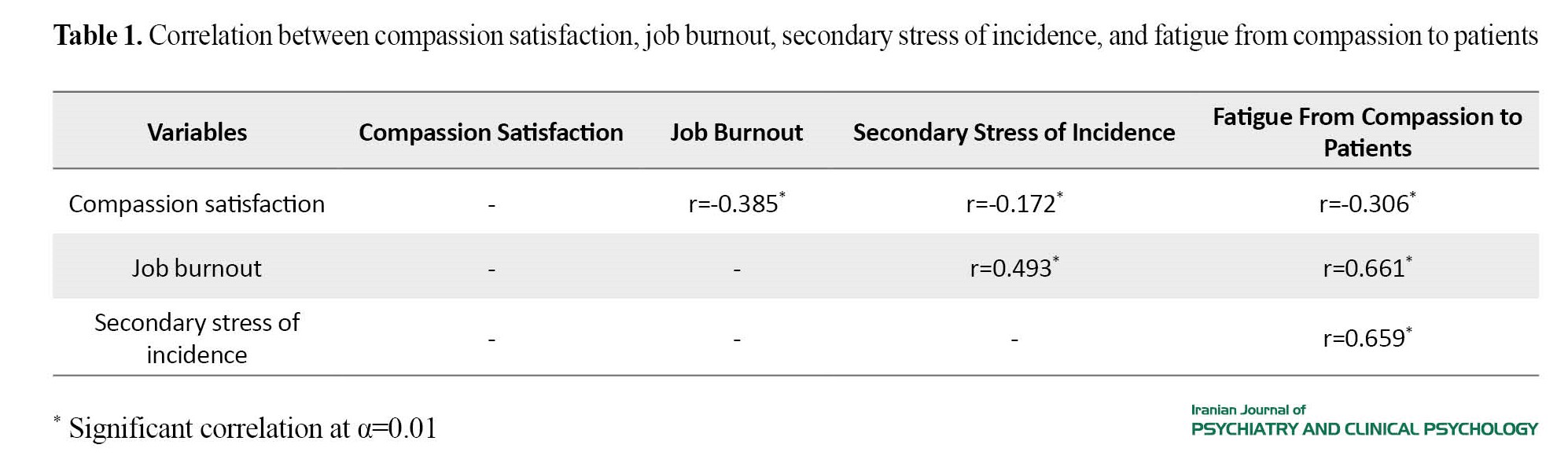

The majority of the participants (73%) were moderately satisfied with compassion, and 58.2% of participants had low job burnout, while in 46.2% of the participants, secondary incident stress was at a medium level. In addition, 59.2% of psychotherapists had very low compassion fatigue and 37% had low levels. The correlation between compassion satisfaction, job burnout, secondary stress of incidence, and fatigue from compassion to patients is shown in Table 1.

Compassion satisfaction was at a moderate level in participants who had family therapy and an existential approach. Participants with a family therapy approach did not have medium and high levels of job burnout. Moderate levels of secondary stress were frequent in all the investigated approaches. The level of fatigue from compassion with patients was mostly low and very low. There was no significant relationship between work approach and the level of satisfaction with compassion, job burnout, secondary stress of the incident, and compassion fatigue among the participants (P<0.05). Age had a direct and significant relationship with compassion satisfaction (r=0.254, p<0.001), while work experience had an indirect and significant relationship with compassion fatigue (r=0.146, p=0.048). There was no significant relationship between the level of compassion satisfaction, job burnout, incident secondary stress, and compassion fatigue and the type of employment and work in the academic field among the participants (p<0.05).

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that the level of satisfaction of compassion in most therapists was moderate, and job burnout and secondary stress levels of the accident in most therapists were moderate to low, and fatigue of compassion level was very low in most participants, which was in contrast with the findings of a study on 240 psychotherapists in Canada [9]. Contradictory findings of these studies may indicate the impact of other social and working factors on occupational depression and the quality of life of psychotherapists. It can be stated that in the present study, psychotherapists maintained their level of job satisfaction and quality of life by reducing their emotional involvement with clients.

This conclusion was in agreement with the findings of the present study regarding the positive and significant relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue and the relationship between compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress.

This conclusion was in agreement with the findings of the present study regarding the positive and significant relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue and the relationship between compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress.

The present study also showed a significant and indirect relationship between compassion satisfaction and job exhaustion, secondary stress of the accident, and fatigue from compassion among the therapists. This finding was in line with the findings of a previous study [10].

This study showed no significant relationship between gender, work approach, the type of employment, age, and work experience of psychotherapists and compassion satisfaction, job exhaustion, secondary stress, and fatigue from compassion. The findings of previous studies are controversial [9-12]. The reason for this difference might be due to the effects of gender, sample size, and differences in study instruments. It is recommended that future studies be conducted with a larger population and based on cluster sampling to impact the job and gender on the quality of life of psychotherapists.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUMS.REC.1400.401).

Funding

This study was funded by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Nafise Nouri Siahdasht and Ali Reza Javdani Asl; Data analysis: Saeede Hajebi Khaniki; Edit and review: Negar Asgharipour.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the deputy for research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and all psychiatrists and psychotherapists participated in the study for their support and cooperation.

The daily activities of psychotherapists require close cooperation with people who are in mental distress and suffer from various mental disorders. Psychotherapy is based on communication and emotional capacities that are used during therapy sessions and can cause emotional traumas to therapists and affect their professional quality of life [1]. Three main factors, including job burnout, fatigue from compassion, and secondary traumatic stress injury, can influence the quality of life of therapists.

Job burnout is an important issue among psychologists and psychotherapists that affects 20-67% of working psychotherapists [2, 3]. The level of emotional exhaustion in working psychologists was reported higher than in other health and treatment staff [4].

Fatigue from compassion is defined as frustration and exhaustion from compassion in patient care, where the caregiver feels frustrated due to observing the devastating injury and illness of patients [3]. The symptoms are presented as physical exhaustion and appear in the form of physical fatigue while other symptoms of this condition may range from symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress syndrome to nervousness and anxiety, decreased self-confidence, and physical symptoms, such as headache and dizziness [5, 6].

Secondary traumatic stress injury is defined as indirect exposure to a traumatic event [7]. The symptoms are similar to the symptoms of post-traumatic stress along with positive changes in self-understanding, interpersonal relationships with others, and philosophy of life [8].

The factors influencing professional quality of life in psychotherapists have not been well investigated and there is no consensus in this regard. Considering that similar studies have not been conducted in Iran, especially in Mashhad the second largest city in Iran, the purpose of this study was to investigate the quality of professional life of psychotherapists.

Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on psychologists and psychiatrists working in Mashhad City in 2022 based on convenience sampling methods. The inclusion criteria were psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors working in Mashhad, and willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were incomplete questionnaires, the presence of a specific pattern in answering questions, and choosing two or more choices for more than five questions.

Data were collected using a questionnaire comprised of demographic information (age and gender), job information (type of employment and work approach), and Stam’s quality of professional life questionnaire (2009). The questionnaire has 30 items and three components, including satisfaction from compassion, secondary traumatic stress, and job burnout (ten items for each component).

Participants were informed about the study through email and social media platforms. Psychotherapists who were working in Mashhad at the time of conducting the research (based on self-report) completed the questionnaires through the link sent in the invitation message.

Results

A total of 184 participants (91, 49.5% men and 93, 50.5% women) were studied. The average age of all subjects was 37.4±7.6 years. There was no significant difference in terms of age between genders. Also, 46.7% (86 people) were contractually employed, 35.9% (66 people) were officially employed, and 17.4% (32 people) were on duty. The average working experience of the participants was 6.5±6.6 years.

The majority of the participants (73%) were moderately satisfied with compassion, and 58.2% of participants had low job burnout, while in 46.2% of the participants, secondary incident stress was at a medium level. In addition, 59.2% of psychotherapists had very low compassion fatigue and 37% had low levels. The correlation between compassion satisfaction, job burnout, secondary stress of incidence, and fatigue from compassion to patients is shown in Table 1.

Compassion satisfaction was at a moderate level in participants who had family therapy and an existential approach. Participants with a family therapy approach did not have medium and high levels of job burnout. Moderate levels of secondary stress were frequent in all the investigated approaches. The level of fatigue from compassion with patients was mostly low and very low. There was no significant relationship between work approach and the level of satisfaction with compassion, job burnout, secondary stress of the incident, and compassion fatigue among the participants (P<0.05). Age had a direct and significant relationship with compassion satisfaction (r=0.254, p<0.001), while work experience had an indirect and significant relationship with compassion fatigue (r=0.146, p=0.048). There was no significant relationship between the level of compassion satisfaction, job burnout, incident secondary stress, and compassion fatigue and the type of employment and work in the academic field among the participants (p<0.05).

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that the level of satisfaction of compassion in most therapists was moderate, and job burnout and secondary stress levels of the accident in most therapists were moderate to low, and fatigue of compassion level was very low in most participants, which was in contrast with the findings of a study on 240 psychotherapists in Canada [9]. Contradictory findings of these studies may indicate the impact of other social and working factors on occupational depression and the quality of life of psychotherapists. It can be stated that in the present study, psychotherapists maintained their level of job satisfaction and quality of life by reducing their emotional involvement with clients.

This conclusion was in agreement with the findings of the present study regarding the positive and significant relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue and the relationship between compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress.

This conclusion was in agreement with the findings of the present study regarding the positive and significant relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue and the relationship between compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress.

The present study also showed a significant and indirect relationship between compassion satisfaction and job exhaustion, secondary stress of the accident, and fatigue from compassion among the therapists. This finding was in line with the findings of a previous study [10].

This study showed no significant relationship between gender, work approach, the type of employment, age, and work experience of psychotherapists and compassion satisfaction, job exhaustion, secondary stress, and fatigue from compassion. The findings of previous studies are controversial [9-12]. The reason for this difference might be due to the effects of gender, sample size, and differences in study instruments. It is recommended that future studies be conducted with a larger population and based on cluster sampling to impact the job and gender on the quality of life of psychotherapists.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUMS.REC.1400.401).

Funding

This study was funded by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Nafise Nouri Siahdasht and Ali Reza Javdani Asl; Data analysis: Saeede Hajebi Khaniki; Edit and review: Negar Asgharipour.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the deputy for research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and all psychiatrists and psychotherapists participated in the study for their support and cooperation.

References:

- Houck D. Helping nurses cope with grief and compassion fatigue: An educational intervention. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014; 18(4):454-8. [DOI:10.1188/14.CJON.454-458] [PMID]

- Sansó N, Galiana L, Oliver A, Tomás-Salvá M, Vidal-Blanco G. Predicting professional quality of life and life satisfaction in Spanish nurses: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4366. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17124366] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Farber DJE, Payton DC, Dorney DP. Life balance and professional quality of life among baccalaureate nurse faculty. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2020; 36(6):587-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.08.010] [PMID]

- Joinson C. Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing. 1992; 22(4):116-20. [DOI:10.1097/00152193-199204000-00035] [PMID]

- Xie W, Chen L, Feng F, Okoli CTC, Tang P, Zeng L, et al. The prevalence of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2021; 120:103973.[DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103973] [PMID]

- Mottaghi S, Poursheikhali H, Shameli L. Empathy, compassion fatigue, guilt and secondary traumatic stress in nurses. Nursing Ethics. 2020; 27(2):494-504.[DOI:10.1177/0969733019851548] [PMID]

- Singer J, Cummings C, Boekankamp D, Hisaka R, Benuto LT. Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout: A replication study with victim advocates. Journal of Social Service Research. 2020; 46(3):313-9. [DOI:10.1080/01488376.2018.1561595]

- Jimenez RR, Andersen S, Song H, Townsend C. Vicarious trauma in mental health care providers. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice. 2021; 24:100451. [DOI:10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100451]

- Lee J, Daffern M, Ogloff JR, Martin T. Towards a model for understanding the development of post-traumatic stress and general distress in mental health nurses. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2015; 24(1):49-58. [DOI:10.1111/inm.12097] [PMID]

- Tununu AF, Martin P. Prevalence of burnout among nurses working at a psychiatric hospital in the Western Cape. Curationis. 2020; 43(1):e1-7. [DOI:10.4102/curationis.v43i1.2117] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lim S, Song Y, Nam Y, Lee Y, Kim D. Moderating effect of burnout on the relationship between self-efficacy and job performance among psychiatric nurses for COVID-19 in national hospitals. Medicina. 2022; 58(2):171. [DOI:10.3390/medicina58020171] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Jin R. Job satisfaction and burnout of psychiatric nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in China-the moderation of family support. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022; 13:1006518. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1006518] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Yang Y, Hayes JA. Causes and consequences of burnout among mental health professionals: A practice-oriented review of recent empirical literature. Psychotherapy. 2020; 57(3):426-36. [DOI:10.1037/pst0000317] [PMID]

- Manning-Jones SF. Vicarious traumatic exposure among New Zealand health professionals: An exploration of coping strategies and vicarious posttraumatic growth [PhD Thesis]. Wellington: Massey University; 2016. [Link]

- Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists' chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002; 58(11):1433-41. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.10090] [PMID]

- Figley CR. Treating compassion fatigue. New York: Routledge; 2002. [Link]

- Khamisa N, Peltzer K, Ilic D, Oldenburg B. Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses: A follow-up study. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2016; 22(6):538-45. [DOI:10.1111/ijn.12455] [PMID]

- Măirean C. Emotion regulation strategies, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction in healthcare providers.The Journal of Psychology. 2016; 150(8):961-75. [DOI:10.1080/00223980.2016.1225659] [PMID]

- Sales JM, Piper K, Riddick C, Getachew B, Colasanti J, Kalokhe A. Low provider and staff self-care in a large safety-net HIV clinic in the Southern United States: Implications for the adoption of trauma-informed care. Sage Open Medicine. 2019; 7:2050312119871417. [DOI:10.1177/2050312119871417] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mohammadi S, Borhani F, Roshanzadeh M. [Investigating the level of compassion for patients in special care nurses (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine. 2015; 7(3):26-35. [Link]

- Stamm BH. The ProQOL manual: The professional quality of life scale: Compassion satisfaction, burnout & compassion fatigue/secondary trauma scales. Baltimore: Sidran Press; 2005. [Link]

- Beaumont E, Durkin M, Hollins Martin CJ, Carson J. Measuring relationships between self-compassion, compassion fatigue, burnout and well-being in student counsellors and student cognitive behavioural psychotherapists: A quantitative survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2016; 16(1):15-23. [DOI:10.1002/capr.12054]

- Davies SM, Sriskandarajah S, Staneva AS, Boulton HCM, Roberts C, Shaw SH, et al. Factors influencing ‘burn-out’in newly qualified counsellors and psychotherapists: A cross-cultural, critical review of the literature. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2022; 22(1):64-73. [DOI:10.1002/capr.12485]

- Spännargård Å, Fagernäs S, Alfonsson S. Self-perceived clinical competence, gender and workplace setting predict burnout among psychotherapists. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2022; 23(2):469-77. [DOI:10.1002/capr.12532]

- Laverdière O, Kealy D, Ogrodniczuk JS, Chamberland S, Descôteaux J. Psychotherapists’ professional quality of life. Traumatology. 2019; 25(3):208-15. [DOI:10.1037/trm0000177]

- Demisch AM, Kuchinke L. Do the relationships between age and the personality of psychotherapists differ from expected trajectories? A cross-sectional study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2022; 22(4):970-81. [DOI:10.1002/capr.12529]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2022/10/28 | Accepted: 2023/03/14 | Published: 2023/01/1

Received: 2022/10/28 | Accepted: 2023/03/14 | Published: 2023/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |