BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3064-en.html

2- Department of General Psychology, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. ,

1. Introduction

Suicide is a global phenomenon and occurs throughout the lifespan. Close to 800 thousand people die due to suicide every year which is one person every 40 seconds. There are indications that for each adult who died by suicide there may have been more than 20 others attempting suicide [1]. It is, therefore, critical to identify the factors that influence suicidal behavior. This study aimed to predict suicide ideation based on the attentional bias in clinical and non-clinical populations.

2. Methods

Participants were 120 individuals (77 women and 43 men) aged 18-40 years who were purposively selected from among suicide attempters and psychiatric outpatients referred to hospitals and medical centers in Tehran as well as non-clinical subjects divided into three groups of clinical-suicidal (n=40), clinical non-suicidal (n=40) and non-clinical (n=40). The criteria for entering study for non-clinical group was having the General Health Questionnaire score of less than 23 [30]. Suicide Stroop Test was used to measure attentional bias in response to positive emotional, negative emotional and suicide-related stimuli, and Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation [37, 38] was used to measure the suicidal thoughts. Three indices of attentional bias including reaction time, time interference and interference ratio were calculated and the data were analyzed using paired-samples t-test, Pearson correlation coefficient and multivariate regression analysis at the 95% confidence level.

3. Results

The longest reaction time and the highest time interference for suicide-related words were observed in the clinical-suicidal group (32.887±130.76 ms). Regardless of the group type, the fastest and slowest reaction times were related to the positive emotional Stroop (-24.325±151.12 ms) and suicide Stroop (11.58±160.30 ms), respectively. Paired t-test results showed no significant difference in mean reaction time between all types of Stroop tests (positive emotional, negative emotional, and suicide) in comparison to the neutral Stroop (P<0.05). However, at 90% confidence level, the mean reaction time for the positive emotional Stroop in the non-suicidal clinical group (ΔM=59.30 ms, t=-1.71, P=0.09) and the overall reaction time (ΔM=24.32 ms, t=-1.76, P=0.08) were faster than those of the neutral Stroop.

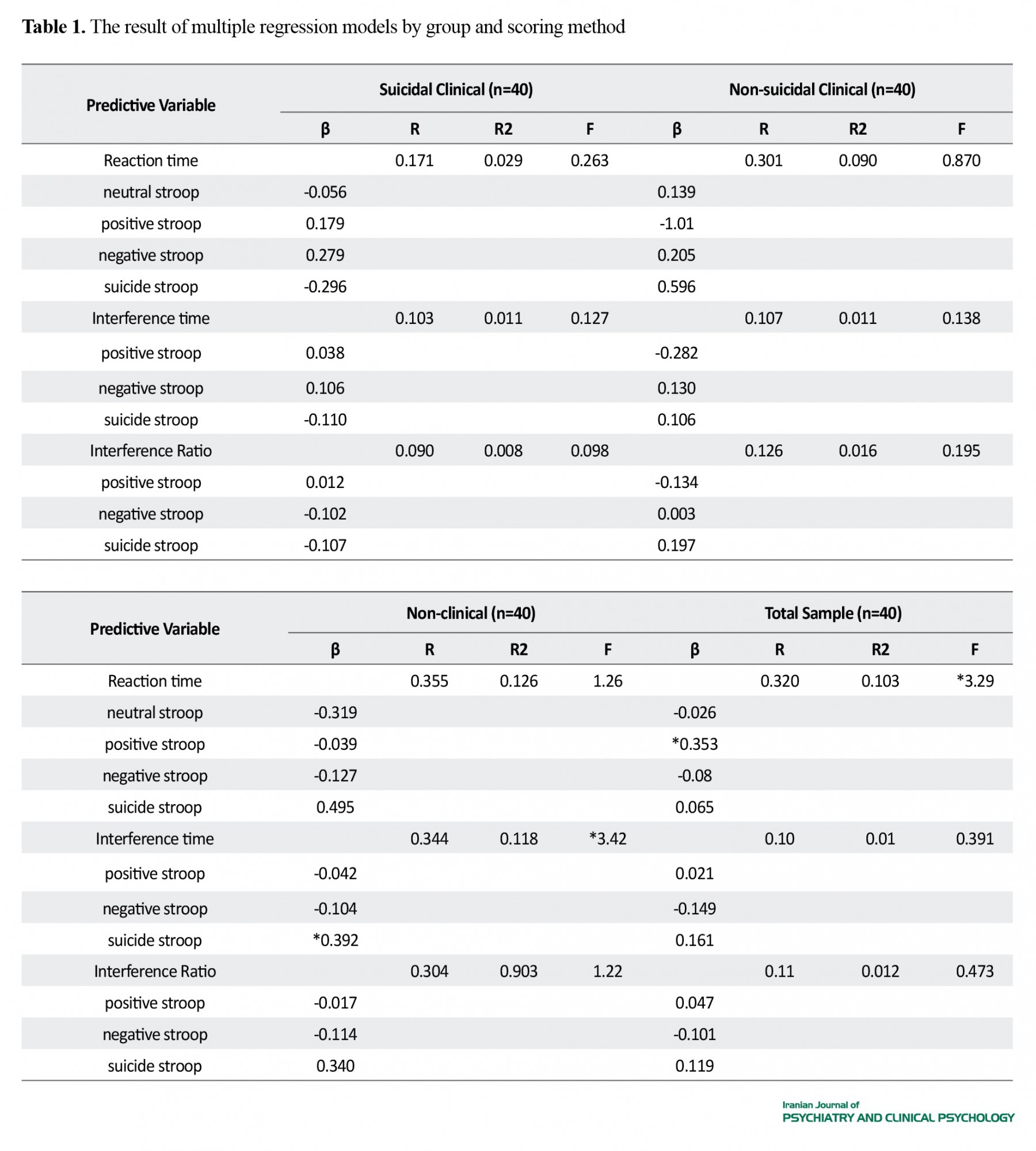

Moreover, 11.8% of the variance in suicide ideation of the non-clinical group was explained by attentional bias in the suicide Stroop (β=0.392), but no other variables had a significant role in explaining changes in suicide ideation after controlling for the role of demographic and general health variables in the non-clinical group (P>0.05). In overall, age (β=-0.225), gender (β=0.223), clinical conditions (β=0.224) and recent suicide attempt (β=0.424) explaining 44% of the variances, were significant determinants of suicide ideation and attentional bias indices failed to play any significant role in predicting suicide ideation (P>0.05) (Table 1).

4. Discussion

The clinical and non-clinical population investigated in this study did not show significant attentional bias in the suicide Stroop; hence, it seems that the incidence of attentional bias towards suicide-related information is not related to clinical conditions. Chung and Jaglic (2016), Richard-Devantoy et al. (2016) and Wilson et al. (2019), reported no significant difference between the reaction times of neutral, positive emotional, negative emotional, and suicide Stroop tests [9-11] which is consistent with the findings of the present study. However, Becker et al. (1999) and William and Bordbent (1986) reported that the reaction time of suicide Stroop in suicide attempters was significantly longer than that of other types of Stroop tests [12, 13].

According to the present study, age, gender, clinical status, and past suicidal behaviors were significant predictors of suicide ideation, but the indices of attentional bias towards suicide-related information could not predict suicide ideation. Most of the studies in literature have studied the predictive power of attentional bias in relation to suicide attempt, but regarding the suicide ideation, only a simple relationship between attentional bias and suicide ideation has been reported. Most of these studies have shown that there is no significant correlation between attentional bias in suicide strop and suicide ideation [9, 10], but in other stuides, a weak to moderate correlation between attentional bias and suicide ideation has been reported [12].

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this study. The participants were informed about the study objectives and methods, and signed a written consent form; they were also assured of the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, they were allowed to leave the study at any time, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

1.World Health Organization. Suicide data [Internet]. 2018 [Updated 2018].

Available from: www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en

2.Young Journalists Club. [The latest suicide statistics in Iran (Persian)] [Internet]. 2018 [Updated 2018 September 8]. Available from: www.yjc.ir/00Rwd6

3.Hamedi A, Colborn VA, Bell M, Chalker SA, Jobes DA. Attentional bias and the Suicide Status Form: Behavioral perseveration of written responses. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019; 120:103403. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.04.011] [PMID]

4.Cyders MA, Coskunpinar A. Measurement of constructs using self-report and behavioral lab tasks: Is there overlap in nomothetic span and construct representation for impulsivity? Clinical Psychology Review. 2011; 31(6):965-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.001] [PMID]

5.Goodman M. Affective startle and suicide risk. Paper presented at: The Suicide Prevention Research Interim Progress Report Meeting, Military Operational Medicine Research Program, May 2012; Ft. Detrick, MD, USA.

6.Goodman M. High-risk suicidal behavior in veterans: Assessment and predictors and efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy. Paper presented at: The Suicide Prevention Research Interim Progress Report Meeting, Military Operational Medicine Research Program, May 2015; Ft. Detrick, MD, USA.

7.Familoni BO, Ma L, Andrew Hutchinson J, Andrew Morgan C, Rasmusson A, O’Kane BL. SAFE for PTSD: Noncontact psychophysiological measure based on high-resolution thermal imaging to aid in PTSD diagnosis and assessment of treatment. Paper presented at: SPIE 8401, Independent Component Analyses, Compressive Sampling, Wavelets, Neural Net, Biosystems, and Nanoengineering. 10 May 2012; Baltimore, Maryland, United States. [DOI:10.1117/12.926464]

8.Nock MK, Park JM, Finn CT, Deliberto TL, Dour HJ, Banaji MR. Measuring the suicidal mind: Implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychological Science. 2010; 21(4):511-7. [DOI:10.1177/0956797610364762] [PMID] [PMCID]

9.Chung Y, Jeglic EL. Use of the modified emotional Stroop task to detect suicidality in college population. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2016; 46(1):55-66. [DOI:10.1111/sltb.12174] [PMID]

10.Richard-Devantoy S, Ding Y, Turecki G, Jollant F. Attentional bias toward suicide-relevant information in suicide attempters: A cross-sectional study and a meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016; 196:101-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.046] [PMID]

11.Wilson KM, Millner AJ, Auerbach RP, Glenn CR, Kearns JC, Kirtley OJ, et al. Investigating the psychometric properties of the suicide stroop task. Psychological Assessment. 2019; 31(8):1052-61. [DOI:10.1037/pas0000723] [PMID] [PMCID]

12.Becker ES, Strohbach D, Rinck M. A specific attentional bias in suicide attempters. The Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1999; 187(12):730-5. [DOI:10.1097/00005053-199912000-00004] [PMID]

13.Williams JM, Broadbent K. Autobiographical memory in suicide attempters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986; 95(2):144-9. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.95.2.144] [PMID]

14.Cha CB, Najmi S, Park JM, Finn CT, Nock MK. Attentional bias toward suicide-related stimuli predicts suicidal behavior. ournal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010; 119(3):616-22. [DOI:10.1037/a0019710] [PMID] [PMCID]

15.Stewart JG, Glenn CR, Esposito EC, Cha CB, Nock MK, Auerbach RP. Cognitive control deficits differentiate adolescent suicide ideators from attempters. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2017; 78(6):e614-e21. [DOI:10.4088/JCP.16m10647] [PMID]

16.Johnson A, Proctor RW. Attention: Theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2004. [DOI:10.4135/9781483328768]

17.Sohlberg MM, Mateer CA. Introduction to cognitive rehabilitation: Theory and practice. New York: Guilford Publications; 1989. https://books.google.com/books?id=-d9mQgAACAAJ&dq

18.Notebaert L, Chrystal J, Clarke PJF, Holmes EA, MacLeod C. When we should worry more: Using cognitive bias modification to drive adaptive health behaviour. PLoS One. 2014; 9(1):e85092. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0085092] [PMID] [PMCID]

19.Williams JM, Mathews A, MacLeod C. The emotional Stroop task and psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin. 1996; 120(1):3-24. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.3] [PMID]

20.Spanakis P, Jones A, Field M, Christiansen P. A stroop in the hand is worth two on the laptop: Superior reliability of a smartphone based alcohol stroop in the real world. Substance Use & Misuse. 2019; 54(4):692-8. [DOI:10.1080/10826084.2018.1536716] [PMID]

21.Drobes DJ, Oliver JA, Correa JB, Evans DE. Attentional bias and smoking. In: Preedy VR, editor. Neuroscience of Nicotine: Mechanisms and Treatment. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2019. pp. 145-50. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-813035-3.00018-6]

22.DeVito EE, Kiluk BD, Nich C, Mouratidis M, Carroll KM. Drug Stroop: Mechanisms of response to computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for cocaine dependence in a randomized clinical trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018; 183:162-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.022] [PMID] [PMCID]

23.van Timmeren T, Daams JG, van Holst RJ, Goudriaan AE. Compulsivity-related neurocognitive performance deficits in gambling disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018; 84:204-17. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.022] [PMID]

24.Cisler JM, Bacon AK, Williams NL. Phenomenological characteristics of attentional biases towards threat: A critical review. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2009; 33(2):221-34. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-007-9161-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

25.Wenzel A, Brown GK, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for suicidal patients: Scientific and clinical applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [DOI:10.1037/11862-000]

26.Chung Y, Jeglic EL. Detecting suicide risk among college students: A test of the predictive validity of the modified emotional Stroop task. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2017; 47(4):398-409. [DOI:10.1111/sltb.12287] [PMID]

27.Cha CB, Najmi S, Amir N, Matthews JD, Deming CA, Glenn JJ, et al. Testing the efficacy of attention bias modification for suicidal thoughts: Findings from two experiments. Archives of Suicide Research. 2017; 21(1):33-51. [DOI:10.1080/13811118.2016.1162241] [PMID]

28.Cha CB, O’Connor RC, Kirtley O, Cleare S, Wetherall K, Eschle S, et al. Testing mood-activated psychological markers for suicidal ideation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2018; 127(5):448-57. [DOI:10.1037/abn0000358] [PMID]

29.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. https://books.google.com/books?id=cIJH0lR33bgC&dq

30.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychological Medicine. 1979; 9(1):139-45. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291700021644] [PMID]

31.Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire: A technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. London: Oxford University Press; 1972. https://books.google.com/books?id=3schAQAAMAAJ&dq

32.Rezaei S, Salehi I, Yousefzadeh Chabok Sh, Moosavi H, Kazemnejad E. [Factor structure, clinical cut off point and psychometric properties of 28-items version for general health questionnaire in patients with traumatic brain injury (Persian)]. Journal of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. 2011; 20(78):56-70. http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-148-en.html

33.Prady SL, Miles JNV, Pickett KE, Fairley L, Bloor K, Gilbody S, et al. The psychometric properties of the subscales of the GHQ-28 in a multi-ethnic maternal sample: Results from the Born in Bradford cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2013; 13:55. [DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-13-55] [PMID] [PMCID]

34.Willmott SA, Boardman J, Henshaw C, Jones P. The predictive power and psychometric properties of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28). Journal of Mental Health. 2008; 17(4):435-42. [DOI:10.1080/09638230701528485]

35.Noorbala AA, Bagheri-Yazdi SA, Mohammad K. [The validation of general health questionnaire-28 as a psychiatric screening tool (Persian)]. Hakim Research Journal. 2009; 11(4):47-53. http://hakim.hbi.ir/article-1-464-en.html

36.Salehi Fadardi J, Ziaei SS. [Implicit cognitive processes and attention bias toward addictive behaviors: Introduction, development and application of addiction stroop test (Persian)]. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2010; 12(45):358-89. [DOI:10.22038/JFMH.2010.886]

37.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicide ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979; 47(2):343-52. [DOI:10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.343] [PMID]

38.Beck AT. BSI, Beck scale for suicide ideation: Manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1991. https://books.google.com/books?id=bFFSHAAACAAJ&dq

39.Anisi J, Fathi Ashtiani A, Salimi SH, Ahmadi Nodeh Kh. [Validity and reliability of beck suicide scale ideation among soldiers (Persian)]. Journal of Military Medicine. 2005; 7(1):33-7. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=22790

40.Wenzel A, Beck AT. A cognitive model of suicidal behavior: Theory and treatment. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2008; 12(4):189-201. [DOI:10.1016/j.appsy.2008.05.001]

41.Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Sherry SB, Caelian C. Trait perfectionism dimensions and suicidal behavior. In: Ellis TE, editor. Cognition and Suicide: Theory, Research, and Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 215-35. [DOI:10.1037/11377-010]

42.Azad M, Abdollahi MH, Hasani J. [Cognitive emotion regulation strategies in processing suicidal thoughts (Persian)]. Journal of Ilam University of Medical Sciences. 2014; 22(4):225-35. http://sjimu.medilam.ac.ir/article-1-1289-en.html

43.Hasani J, Miraghaie AM. [The relationship between strategies for cognitive regulation of emotions and suicidal ideation (Persian)]. Contemporary Psychology. 2012; 7(1):61-72. http://bjcp.ir/article-1-26-en.html

44.Ghoreishi SA, Mousavinasab N. [Systematic review of researches on suicide and suicide attempt in Iran (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2008; 14(2):115-21. http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-460-en.html

Received: 2019/08/11 | Accepted: 2019/12/11 | Published: 2020/04/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |