Tue, Jan 27, 2026

| فارسی

Volume 31, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

IJPCP 2025, 31(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nasri E, Yousefi S, Ashouri A. Investigating the Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the International Adjustment Disorder Questionnaire Among University Students in Tehran City, Iran. IJPCP 2025; 31 (1)

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4290-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4290-en.html

1- Student Research Committee, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ahmad.ashouri@gmail.com

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: The international adjustment disorder questionnaire (IADQ), Adjustment disorder (AjD), Psychometrics, Stress-related disorders, Traum

Full-Text [PDF 8107 kb]

(740 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1146 Views)

Full-Text: (963 Views)

Introduction

Adjustment disorder (AjD) is characterized as an excessive or unhealthy emotional or behavioral response to a stressful life event or change, with symptoms emerging within three months of the event [1]. Unlike post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder (ASD), AjD does not require exposure to a traumatic event; stressors such as divorce, bereavement, job loss, or financial difficulties may trigger its onset [2–4]. According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), AjD is subdivided into various presentations, including those with depressed mood, anxiety, mixed symptoms, and others, with symptoms appearing within 3 months and resolving within 6 months after the stressor has ceased [3, 5]. Conversely, ICD-11 conceptualizes AjD primarily through two core features: preoccupation with the stressor and failure to adapt, with symptoms emerging within 1 month and resulting in significant functional impairment [3, 7].

Several psychometric tools have been developed to assess AjD. While the widely used (the AjD–new module) ADNM-20 measures both core and additional non-ICD symptoms, concerns exist regarding its alignment with ICD-11 criteria [8–11]. The international adjustment disorder questionnaire (IADQ) was developed to reflect ICD-11 guidelines precisely. The IADQ offers a brief, clinically useful self-report measure with robust psychometric properties demonstrated across diverse populations [10, 22].

Given the academic and life stressors students encounter, establishing a culturally adapted and validated tool is essential. This study aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian IADQ among Tehran university students, facilitating early diagnosis and intervention to improve mental health and academic outcomes. Validating the Persian IADQ will improve early intervention for student mental health.

Methods

A cross-sectional psychometric study involved 495 students from various universities in Tehran, Iran, aged 18-50. The sample was chosen using convenience sampling, and data collection was carried out between January 10 and March 12, 2024. Participants completed the IADQ, international depression questionnaire (IDQ), international trauma questionnaire (ITQ), prolonged grief-13-revised (PG-13-R), and international anxiety questionnaire (IAQ). Before translation, permission was obtained from the scale’s developers to adapt and validate the IADQ into Persian. The translation process followed standard procedures for cross-cultural adaptation. Two independent translators translated the questionnaire into Persian, followed by a back-translation into English by another expert. The final version was confirmed after review by clinical psychology and psychiatry experts. Data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood ratio (MLR) and the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) in Mplus, and reliability tests, including Cronbach α and McDonald omega, were conducted to assess internal consistency. The Pearson correlations were calculated to establish convergent validity.

Results

This study involved 495 participants with a mean age of 23.41±9.74 years, comprising 334 women (67.5%) and 161 men (32.5%). The sample included 396 singles (80%), 89 married individuals (17.9%), and 10 divorced individuals (2.1%). Regarding education, 263(53.1%) held associate’s or bachelor’s degrees, 137(27.7%) had master’s or PhD degrees, and 98(19.2%) were general practitioners.

Most participants experienced 1-3 stressful events (80%), 17.7% experienced 4-6 events, and 2.3% faced 7-9 events. Common stressors included financial issues (40.4%), relationship problems (30.2%), academic challenges (29.4%), and job-related issues (28%). Health issues (22.1%) and housing problems (19.1%) were also prevalent, while health issues of loved ones (17.5%) and caregiving challenges (8.9%) were less common. The Mean±SD number of stressors was 3.4±2.67.

The prevalence of probable AjD was 23.43%. Confirmation rates for the preoccupation factor ranged from 55.6% to 61.4%, while failure to adapt indicators ranged from 48.8% to 51.2%. After controlling for depression, anxiety, and prolonged grief disorder, the prevalence decreased to 7.9%, indicating the impact of diagnostic overlap and the need for precise differentiation.

Reliability analysis showed strong internal consistency, with the Cronbach α and omega coefficients at 0.94 for the total scale and 0.89 and 0.92 for the subscales. The test, re-test reliability was 0.88 for the total scale and 0.85 and 0.84 for subscales over four weeks. Convergent and divergent validity were supported by correlations with PG-13-R (0.49), IDQ (0.59), IAQ (0.64), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (0.14), and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) (0.09).

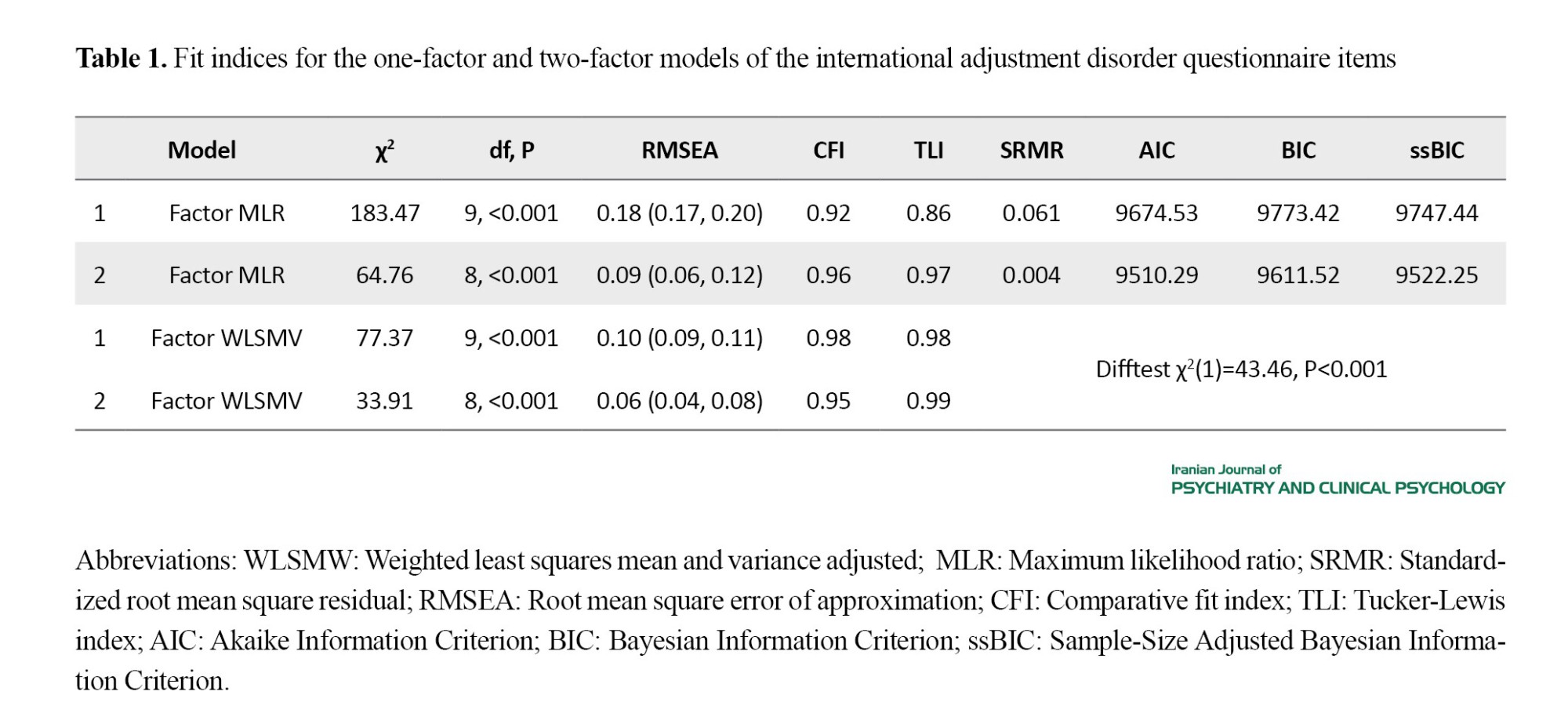

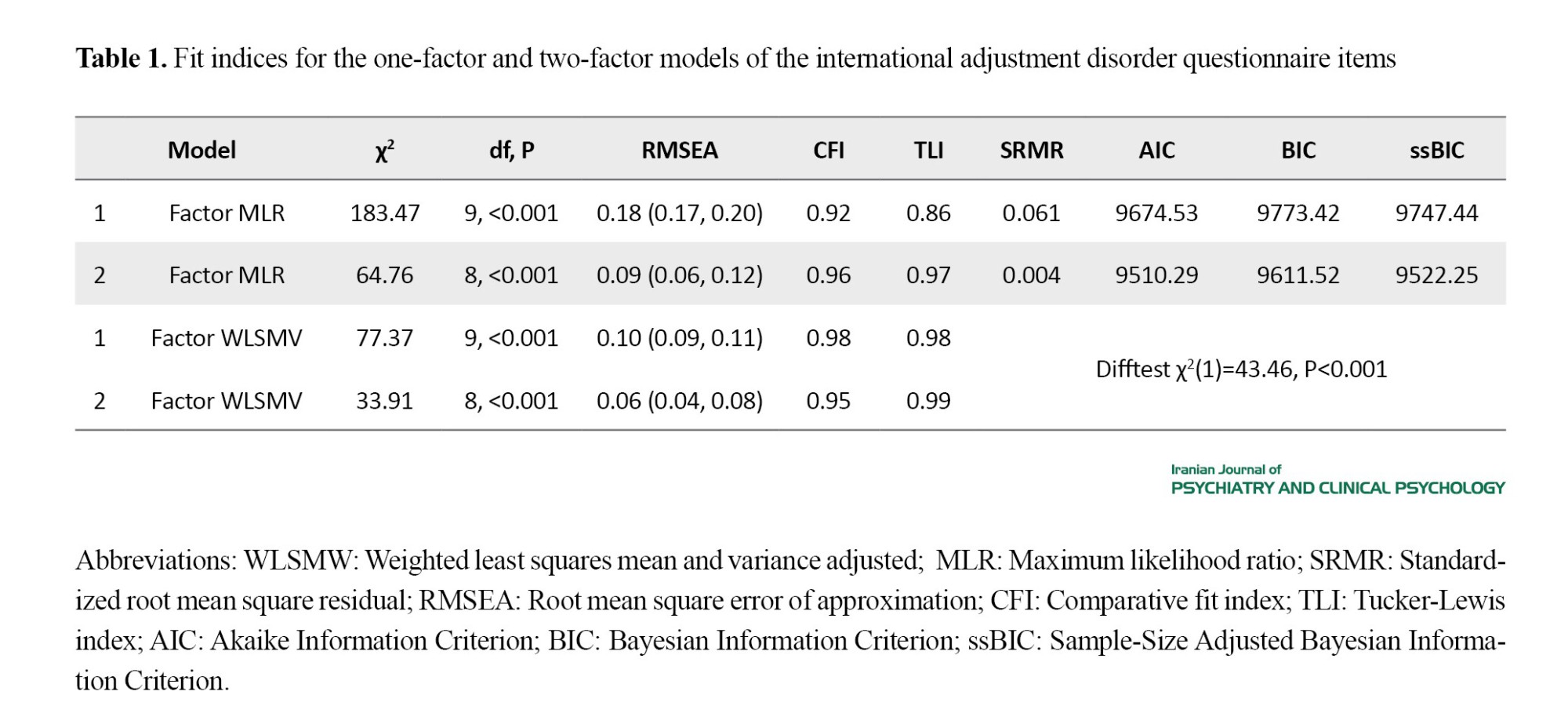

Factor analysis showed that the two-factor model had better fit indices than the one-factor model, with significant differences in χ², standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), AIC, BIC, and ssBIC values. Factor loadings for engagement and maladjustment items were high, positive, and significant. The two-factor model demonstrated excellent fit in Likert and dichotomous coding scenarios (Table 1).

Conclusion

This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the IADQ and assess the prevalence of AjD among students to provide researchers with a valid measure for the Iranian population. Results indicated that after controlling for overlapping disorders like depression, anxiety, and prolonged grief (as defined by ICD-11), the prevalence of AjD was reduced to 7.9%, aligning with a similar Italian study showing a reduction to 8.23% after controlling for these disorders [24]. This finding highlights the importance of precise differential diagnoses and up-to-date criteria, such as ICD-11, to avoid misdiagnosis and manage overlaps between disorders effectively. Moreover, cultural and social contexts, such as the period following the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy, may influence prevalence rates [24]. The study further demonstrated that the Persian IADQ has high internal consistency, with the Cronbach α and omega at 0.94, and excellent test-retest reliability (r=0.88 over four weeks), consistent with other versions [7, 10, 24].

CFA supported the construct validity of the Persian IADQ, revealing a two-factor structure, similar to the original version [7, 10, 24]. The two factors, preoccupation and failure to adapt, were highly correlated, aligning with previous findings [10, 11, 13, 15]. The study also found significant positive correlations between IADQ scores and related measures like PG-13-R, IDQ, and IAQ, supporting concurrent validity [7, 10, 24]. Notably, IADQ showed lower correlations with PTSD and CPTSD, supporting its differential validity [37]. Despite limitations like convenience sampling and self-report measures, which may affect generalizability and introduce response biases, this study provides valuable initial insights into AjD assessment within the Iranian population. Future research should explore clinical samples to establish cut-off points specific to the Iranian context.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The proposal of the study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1402.875). The authors obtained informed consent from participants before collecting demographic information. All participants were informed that participation was voluntary and were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 1401-4-15-25275).

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Methodology: Ahmad Ashouri and Shahab Yousefi; Data Collection: Ebrahim Nasri; Data Analysis and Drafting of the Manuscript: All authors; Editing and Finalization: Ebrahim Nasri; Project Administration: Ahmad Ashouri.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate all the people who helped us plan the study and the data collection, as well as the men and women who voluntarily participated in this study.

Adjustment disorder (AjD) is characterized as an excessive or unhealthy emotional or behavioral response to a stressful life event or change, with symptoms emerging within three months of the event [1]. Unlike post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder (ASD), AjD does not require exposure to a traumatic event; stressors such as divorce, bereavement, job loss, or financial difficulties may trigger its onset [2–4]. According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), AjD is subdivided into various presentations, including those with depressed mood, anxiety, mixed symptoms, and others, with symptoms appearing within 3 months and resolving within 6 months after the stressor has ceased [3, 5]. Conversely, ICD-11 conceptualizes AjD primarily through two core features: preoccupation with the stressor and failure to adapt, with symptoms emerging within 1 month and resulting in significant functional impairment [3, 7].

Several psychometric tools have been developed to assess AjD. While the widely used (the AjD–new module) ADNM-20 measures both core and additional non-ICD symptoms, concerns exist regarding its alignment with ICD-11 criteria [8–11]. The international adjustment disorder questionnaire (IADQ) was developed to reflect ICD-11 guidelines precisely. The IADQ offers a brief, clinically useful self-report measure with robust psychometric properties demonstrated across diverse populations [10, 22].

Given the academic and life stressors students encounter, establishing a culturally adapted and validated tool is essential. This study aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian IADQ among Tehran university students, facilitating early diagnosis and intervention to improve mental health and academic outcomes. Validating the Persian IADQ will improve early intervention for student mental health.

Methods

A cross-sectional psychometric study involved 495 students from various universities in Tehran, Iran, aged 18-50. The sample was chosen using convenience sampling, and data collection was carried out between January 10 and March 12, 2024. Participants completed the IADQ, international depression questionnaire (IDQ), international trauma questionnaire (ITQ), prolonged grief-13-revised (PG-13-R), and international anxiety questionnaire (IAQ). Before translation, permission was obtained from the scale’s developers to adapt and validate the IADQ into Persian. The translation process followed standard procedures for cross-cultural adaptation. Two independent translators translated the questionnaire into Persian, followed by a back-translation into English by another expert. The final version was confirmed after review by clinical psychology and psychiatry experts. Data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood ratio (MLR) and the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) in Mplus, and reliability tests, including Cronbach α and McDonald omega, were conducted to assess internal consistency. The Pearson correlations were calculated to establish convergent validity.

Results

This study involved 495 participants with a mean age of 23.41±9.74 years, comprising 334 women (67.5%) and 161 men (32.5%). The sample included 396 singles (80%), 89 married individuals (17.9%), and 10 divorced individuals (2.1%). Regarding education, 263(53.1%) held associate’s or bachelor’s degrees, 137(27.7%) had master’s or PhD degrees, and 98(19.2%) were general practitioners.

Most participants experienced 1-3 stressful events (80%), 17.7% experienced 4-6 events, and 2.3% faced 7-9 events. Common stressors included financial issues (40.4%), relationship problems (30.2%), academic challenges (29.4%), and job-related issues (28%). Health issues (22.1%) and housing problems (19.1%) were also prevalent, while health issues of loved ones (17.5%) and caregiving challenges (8.9%) were less common. The Mean±SD number of stressors was 3.4±2.67.

The prevalence of probable AjD was 23.43%. Confirmation rates for the preoccupation factor ranged from 55.6% to 61.4%, while failure to adapt indicators ranged from 48.8% to 51.2%. After controlling for depression, anxiety, and prolonged grief disorder, the prevalence decreased to 7.9%, indicating the impact of diagnostic overlap and the need for precise differentiation.

Reliability analysis showed strong internal consistency, with the Cronbach α and omega coefficients at 0.94 for the total scale and 0.89 and 0.92 for the subscales. The test, re-test reliability was 0.88 for the total scale and 0.85 and 0.84 for subscales over four weeks. Convergent and divergent validity were supported by correlations with PG-13-R (0.49), IDQ (0.59), IAQ (0.64), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (0.14), and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) (0.09).

Factor analysis showed that the two-factor model had better fit indices than the one-factor model, with significant differences in χ², standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), AIC, BIC, and ssBIC values. Factor loadings for engagement and maladjustment items were high, positive, and significant. The two-factor model demonstrated excellent fit in Likert and dichotomous coding scenarios (Table 1).

Conclusion

This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the IADQ and assess the prevalence of AjD among students to provide researchers with a valid measure for the Iranian population. Results indicated that after controlling for overlapping disorders like depression, anxiety, and prolonged grief (as defined by ICD-11), the prevalence of AjD was reduced to 7.9%, aligning with a similar Italian study showing a reduction to 8.23% after controlling for these disorders [24]. This finding highlights the importance of precise differential diagnoses and up-to-date criteria, such as ICD-11, to avoid misdiagnosis and manage overlaps between disorders effectively. Moreover, cultural and social contexts, such as the period following the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy, may influence prevalence rates [24]. The study further demonstrated that the Persian IADQ has high internal consistency, with the Cronbach α and omega at 0.94, and excellent test-retest reliability (r=0.88 over four weeks), consistent with other versions [7, 10, 24].

CFA supported the construct validity of the Persian IADQ, revealing a two-factor structure, similar to the original version [7, 10, 24]. The two factors, preoccupation and failure to adapt, were highly correlated, aligning with previous findings [10, 11, 13, 15]. The study also found significant positive correlations between IADQ scores and related measures like PG-13-R, IDQ, and IAQ, supporting concurrent validity [7, 10, 24]. Notably, IADQ showed lower correlations with PTSD and CPTSD, supporting its differential validity [37]. Despite limitations like convenience sampling and self-report measures, which may affect generalizability and introduce response biases, this study provides valuable initial insights into AjD assessment within the Iranian population. Future research should explore clinical samples to establish cut-off points specific to the Iranian context.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The proposal of the study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1402.875). The authors obtained informed consent from participants before collecting demographic information. All participants were informed that participation was voluntary and were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 1401-4-15-25275).

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Methodology: Ahmad Ashouri and Shahab Yousefi; Data Collection: Ebrahim Nasri; Data Analysis and Drafting of the Manuscript: All authors; Editing and Finalization: Ebrahim Nasri; Project Administration: Ahmad Ashouri.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate all the people who helped us plan the study and the data collection, as well as the men and women who voluntarily participated in this study.

References

- O’Donnell ML, Agathos JA, Metcalf O, Gibson K, Lau W. Adjustment disorder: Current developments and future directions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(14):2537. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16142537] [PMID]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (5th ed.). Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International classification of diseases, eleventh revision (ICD-11). 2018 [Updated 2025 May 27]. Available from: [Link]

- Bachem R, Casey P. Adjustment disorder: A diagnosis whose time has come. Journal of affective disorders. 2018; 227:243-53. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.034] [PMID]

- Lorenz L, Hyland P, Maercker A, Ben-Ezra M. An empirical assessment of adjustment disorder as proposed for ICD-11 in a general population sample of Israel. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2018; 54:65-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.007] [PMID]

- Blashfield RK, Keeley JW, Flanagan EH, Miles SR. The cycle of classification: DSM-I through DSM-5. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014; 10(1):25-51. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153639] [PMID]

- Levin Y, Bachem R, Hyland P, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Ben-Ezra M, et al. Validation of the international adjustment disorder questionnaire in Israel and Switzerland. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2022; 29(4):1321-30. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2710] [PMID]

- Yaghubi H, Soleimani L, Abedi Yarandi MS, Mollaei A, Mahdavinoor SM. Prevalence and associated factors of suicide-related behaviors in Iranian students: A large sample cross-sectional study. Middle East Current Psychiatry. 2024; 31(1):88. [DOI:10.1186/s43045-024-00481-y]

- Einsle F, Köllner V, Dannemann S, Maercker A. Development and validation of a self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorders. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2010; 15(5):584-95. [DOI:10.1080/13548506.2010.487107] [PMID]

- Shevlin M, Hyland P, Ben-Ezra M, Karatzias T, Cloitre M, Vallières F, Bachem R, Maercker A. Measuring ICD-11 adjustment disorder: The development and initial validation of the International Adjustment Disorder Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2020; 141(3):265-74. [DOI:10.1111/acps.13126] [PMID]

- Glaesmer H, Romppel M, Brähler E, Hinz A, Maercker A. Adjustment disorder as proposed for ICD-11: Dimensionality and symptom differentiation. Psychiatry Research. 2015; 229(3):940-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.010] [PMID]

- Levin Y, Bachem R, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Maercker A, Ben-Ezra M. Network structure of ICD-11 adjustment disorder: A cross-cultural comparison of three African countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2021; 219(4):557-64. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.2021.46] [PMID]

- Liang L, Ben-Ezra M, Chan EW, Liu H, Lavenda O, Hou WK. Psychometric evaluation of the adjustment disorder new module-20 (ADNM-20): A multi-study analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2021; 81:102406. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102406] [PMID]

- Lorenz L, Bachem RC, Maercker A. The adjustment disorder-new module 20 as a screening instrument: cluster analysis and cut-off values. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2016; 7(4):215. [DOI:10.15171/ijoem.2016.775] [PMID]

- Zelviene P, Kazlauskas E, Eimontas J, Maercker A. Adjustment disorder: Empirical study of a new diagnostic concept for ICD-11 in the general population in Lithuania. European Psychiatry. 2017; 40:20-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.06.009] [PMID]

- Kazlauskas E, Gegieckaite G, Eimontas J, Zelviene P, Maercker A. A brief measure of the International classification of diseases-11 adjustment disorder: Investigation of psychometric properties in an adult help-seeking sample. Psychopathology. 2018; 51(1):10-5. [DOI:10.1159/000484415] [PMID]

- Ben-Ezra M, Mahat-Shamir M, Lorenz L, Lavenda O, Maercker A. Screening of adjustment disorder: Scale based on the ICD-11 and the Adjustment Disorder New Module. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2018; 103:91-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.011] [PMID]

- Ring L, Lavenda O, Hamama-Raz Y, Ben-Ezra M, Pitcho-Prelorentzos S, David UY, et al. Evoked death-related thoughts in the aftermath of terror attack: The associations between mortality salience effect and adjustment disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2018; 206(1):69-71. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000738] [PMID]

- Bachem R, Maercker A. Self-help interventions for adjustment disorder problems: A randomized waiting-list controlled study in a sample of burglary victims. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2016; 45(5):397-413. [DOI:10.1080/16506073.2016.1191083] [PMID]

- Bachem R, Baumann J, Köllner V. ICD-11 adjustment disorder among organ transplant patients and their relatives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(17):3030. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16173030] [PMID]

- First MB, Reed GM, Hyman SE, Saxena S. The development of the ICD-11 clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines for mental and behavioural disorders. World Psychiatry. 2015; 14(1):82-90. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20189] [PMID]

- Vancappel A, Eberle DJ, Chkili R, Kerbage H, Shevlin M, Maercker A, et al. French validation of the International Adjustment Disorder Questionnaire (IADQ) and exploration of its relationship with transdiagnostic skills. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development. 2025. [Link]

- Al-Gburi M, Waleed MA, Shevlin M, Al-Gburi G. Translation and validation of the arabic international adjustment disorder questionnaire among patients with physical illness and their families in Iraq. Chronic Stress. 2025; 9:24705470251332801. [Link]

- Jannini TB, Rossi R, Socci V, Reda F, Pacitti F, Di Lorenzo G. Psychometric and factorial validity of the International Adjustment Disorder Questionnaire (IADQ) in an Italian sample: A validation and prevalence estimate study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2023; 30(2):436-45. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2813] [PMID]

- Perkonigg A, Lorenz L, Maercker A. Prevalence and correlates of ICD-11 adjustment disorder: Findings from the Zurich Adjustment Disorder Study. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2018; 18(3):209-17. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.05.001] [PMID]

- Subudhi C. Culture and mental illness. Paper presented at: International Conference on Social work Practice in Mental Health. 1 December 2014; Kochi, India. [Link]

- Kirmayer LJ. Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 13):22-8. [PMID]

- Choi E, Chentsova-Dutton Y, Parrott WG. The effectiveness of somatization in communicating distress in Korean and American cultural contexts. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016; 7:383. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00383]

- Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. New York: Psychology Press; 2013. [DOI:10.4324/9781315827506]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Pearson; 2013. [Link]

- Myers ND, Ahn S, Jin Y. Sample size and power estimates for a confirmatory factor analytic model in exercise and sport: A monte carlo approach. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2011; 82(3):412-23. [DOI:10.1080/02701367.2011.10599773] [PMID]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999; 6(1):1-55. [DOI:10.1080/10705519909540118]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research. 1992; 21(2):230-58. [DOI:10.1177/0049124192021002005]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978; 6(2):461-4. [DOI:10.1214/aos/1176344136]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology. 1995; 25(1995):111-63. [DOI:10.2307/271063]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992; 1(3):98-101. [DOI:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783]

- Raykov T, Hancock GR. Examining change in maximal reliability for multiple-component measuring instruments. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2005; 58(1):65-82. [DOI:10.1348/000711005X38753] [PMID]

- Irwing P, Hughes DJ. Test development. In: Irwing P, Booth T, Hughes DJ, editors. The Wiley handbook of psychometric testing: A multidisciplinary reference on survey, scale and test development. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2018. [DOI:10.1002/9781118489772.ch1]

- Yousefi S, Abdoli F. Assessing the Persian international trauma questionnaire: A psychometric study. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2024; 8(2):100404. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejtd.2024.100404]

- Ashouri A, Yousefi S, Prigerson HG. Psychometric properties of the PG-13-R scale to assess prolonged grief disorder among bereaved Iranian adults. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2024; 22(1):174-81. [DOI:10.1017/S1478951523000202] [PMID]

- Yousefi S, Mayeli P. [Psychometricproperties of the Persian version of the international depression questionnaire (IDQ) and the international anxiety questionnaire (IAQ) in students of Tehran Medical Sciences Universities (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2023; 33(2):232-46. [Link]

- Keeley JW, Reed GM, Roberts MC, Evans SC, Robles R, Matsumoto C, et al. Disorders specifically associated with stress: A case-controlled field study for ICD-11 mental and behavioural disorders. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2016; 16(2):109-27. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.09.002] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2024/09/7 | Accepted: 2025/05/3 | Published: 2025/08/1

Received: 2024/09/7 | Accepted: 2025/05/3 | Published: 2025/08/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |