Tue, Jan 27, 2026

| فارسی

Volume 31, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

IJPCP 2025, 31(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mohammadi M, Rasouli A, Saed O, Sorahi P, Abbaszadeh S, Shishechi S et al . Factor Structure, Psychometric Properties, and Measurement Invariance of the Persian Version of Beliefs About Emotions Questionnaire (BAEQ) in the Iranian Population. IJPCP 2025; 31 (1)

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4221-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4221-en.html

Mobina Mohammadi1

, Amirhossein Rasouli1

, Amirhossein Rasouli1

, Omid Saed2

, Omid Saed2

, Parisa Sorahi1

, Parisa Sorahi1

, Sahar Abbaszadeh1

, Sahar Abbaszadeh1

, Samane Shishechi1

, Samane Shishechi1

, Seyedeh Elnaz Mousavi3

, Seyedeh Elnaz Mousavi3

, Amirhossein Rasouli1

, Amirhossein Rasouli1

, Omid Saed2

, Omid Saed2

, Parisa Sorahi1

, Parisa Sorahi1

, Sahar Abbaszadeh1

, Sahar Abbaszadeh1

, Samane Shishechi1

, Samane Shishechi1

, Seyedeh Elnaz Mousavi3

, Seyedeh Elnaz Mousavi3

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Student Research Committee, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran. ,dr.emousavi@zums.ac.ir

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 5750 kb]

(989 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1637 Views)

Full-Text: (1126 Views)

Introduction

Emotions are multifaceted, encompassing experiential, behavioral and physiological responses originating from the affective system [1]. They can be positive or negative, arising when stimuli are perceived as goal-relevant [2]. Emotion regulation is the process of monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotions for adaptive responding [3], is crucial for psychological well-being [4]. However, difficulties in emotion regulation can contribute to psychological disorders [5, 6]. Researchers are exploring how individuals’ beliefs about their emotions, nature, characteristics and function influence their regulation efforts [7].

Evidence suggests that beliefs about emotions significantly impact responses to challenges and opportunities [8], playing a key role in emotion regulation, psychopathology, and overall well-being [7, 9-14]. Negative beliefs (e.g. perceiving emotions as dangerous or uncontrollable) are linked to maladaptive strategies and increased risk of disorders [7, 15], while positive beliefs can foster adaptive strategies and improve mental health [16]. Understanding these beliefs can inform effective therapeutic interventions [17].

Existing measures of emotional beliefs often have limitations, such as focusing on a narrow range of beliefs or lacking cultural sensitivity [18]. The beliefs about emotions questionnaire (BAEQ), a comprehensive assessment developed by Manser et al. [19], requires validation across diverse populations. Given cultural and linguistic influences on emotional experience [22], validating the BAEQ, which has seen varying factor structures in different populations [9, 20], for the Iranian population is crucial, especially considering the prevalence of psychological disorders and the need for effective emotion regulation interventions in the country [21]. This study examines the psychometric properties and measurement invariance of a Persian version of the BAEQ, providing a valuable instrument for researchers and clinicians in Iran. This will enable a more accurate assessment of emotional beliefs and facilitate the development of culturally sensitive interventions to improve emotion regulation and psychological well-being.

Methods

This cross-sectional psychometric study was conducted with residents of Zanjan City, Iran. The inclusion criteria for this study were informed consent, minimum education level of eighth grade and age range of 18 to 50 years. The exclusion criterion was the participant’s desire to withdraw from the study and random responses to the items. After the translation and back-translation process, the study questionnaire, including the BAEQ, positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) and satisfaction with life scale (SWLS), was administered to the participants. The participants provided informed virtual consent before completing the questionnaire. The final sample consisted of 453 individuals. All participants were Iranian and were selected using a convenience sampling method.

Descriptive statistics (means and percentages) were used to analyze demographic information. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using principal component analysis to identify the underlying factor structure of the BAEQ. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test and the Bartlett test of sphericity were used to ensure the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the maximum likelihood method to evaluate the factor structure of the BAEQ.

To determine the invariance of the psychometric parameters of the BAEQ across genders (females vs males), measurement invariance was assessed. Internal consistency reliability was assessed using the Cronbach α and composite reliability. Additionally, convergent validity was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE) index, and criterion validity was assessed by examining the correlation of the instrument with the PANAS and the SWLS. The data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 27, for descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis, and AMOS software, version 24 for conformatory factor analysis.

Results

A total of 453 participants were included in this study, with 65.1% (n=295) being female and 34.9% (n=158) being male. The skewness and kurtosis of the variables revealed that all of them were within the range of (-2 to 2), indicating normality.

Exploratory factor analysis using the principal component analysis method and varimax rotation was used to examine the factor structure of the BAEQ. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value obtained was 0.85, indicating sampling adequacy. After performing factor analysis, the scree plot showed 11 factors with eigenvalues greater than one. In contrast, parallel analysis using Monte Carlo software suggested five factors.

The value of 0.4 was considered as the basis for item communality and items with a communality below this value were excluded from further analysis. Consequently, 18 items were removed. The results indicated five factors: Overwhelming and uncontrollable that explained 7.20% of the total variance with an eigenvalue of 6.045; shameful and irrational with 5.12% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 3.83; useless with 8.58% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 3.12; contagious with 6.56% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 1.77 and invalid and meaningless with 5.95% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 1.51. Together, these five factors explained 54% of the total variance.

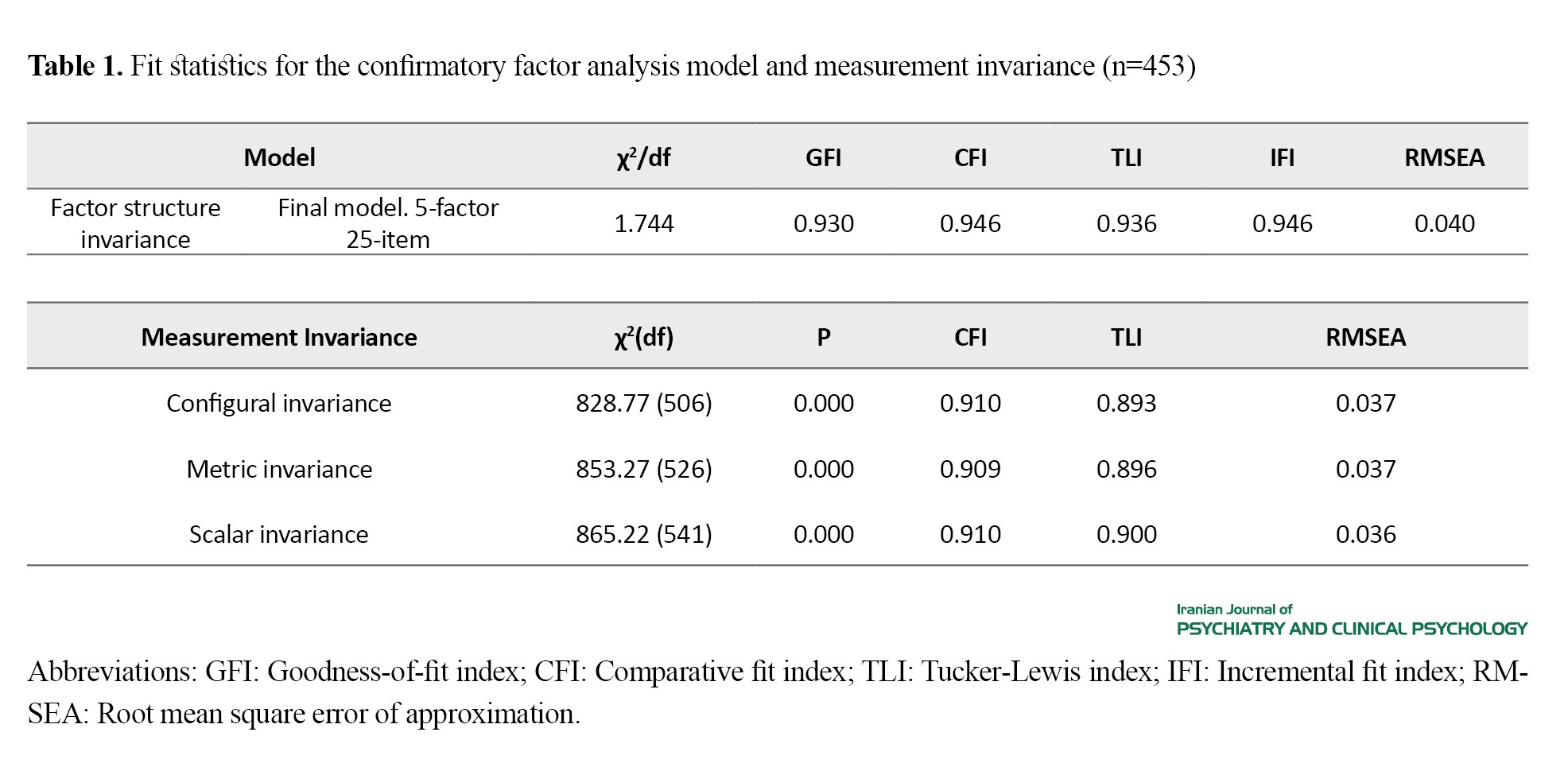

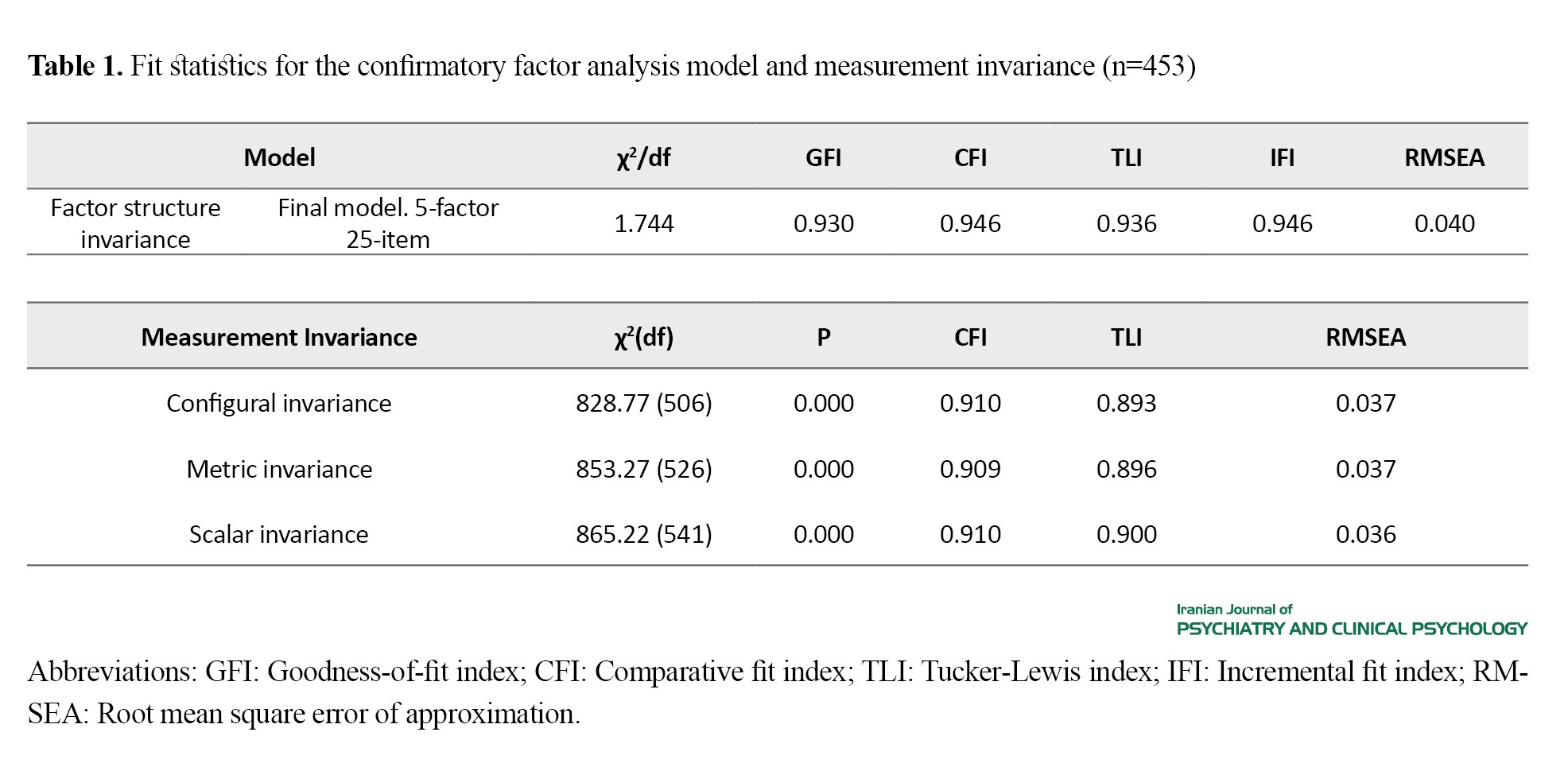

Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the five-factor model has good fit in the Iranian population (Table 1).

The results of the measurement invariance test for the five-factor model showed satisfactory fit indices based on Tucker-Lewis index, comparative fit index, and root mean square error of approximation for both male and female groups. Therefore, based on Chen’s recommendations [30], invariance is established for the five-factor model in both genders (Table 1).

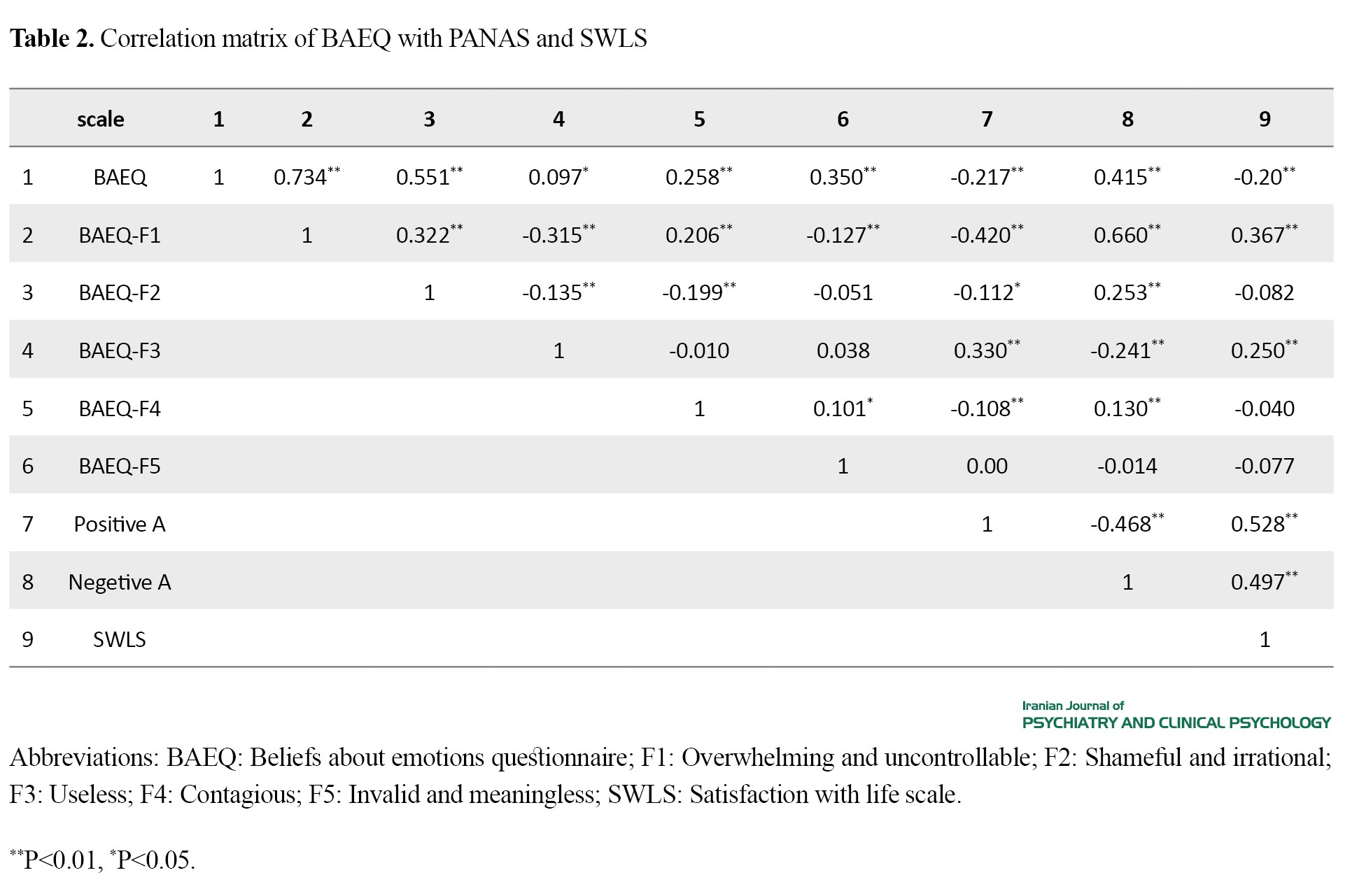

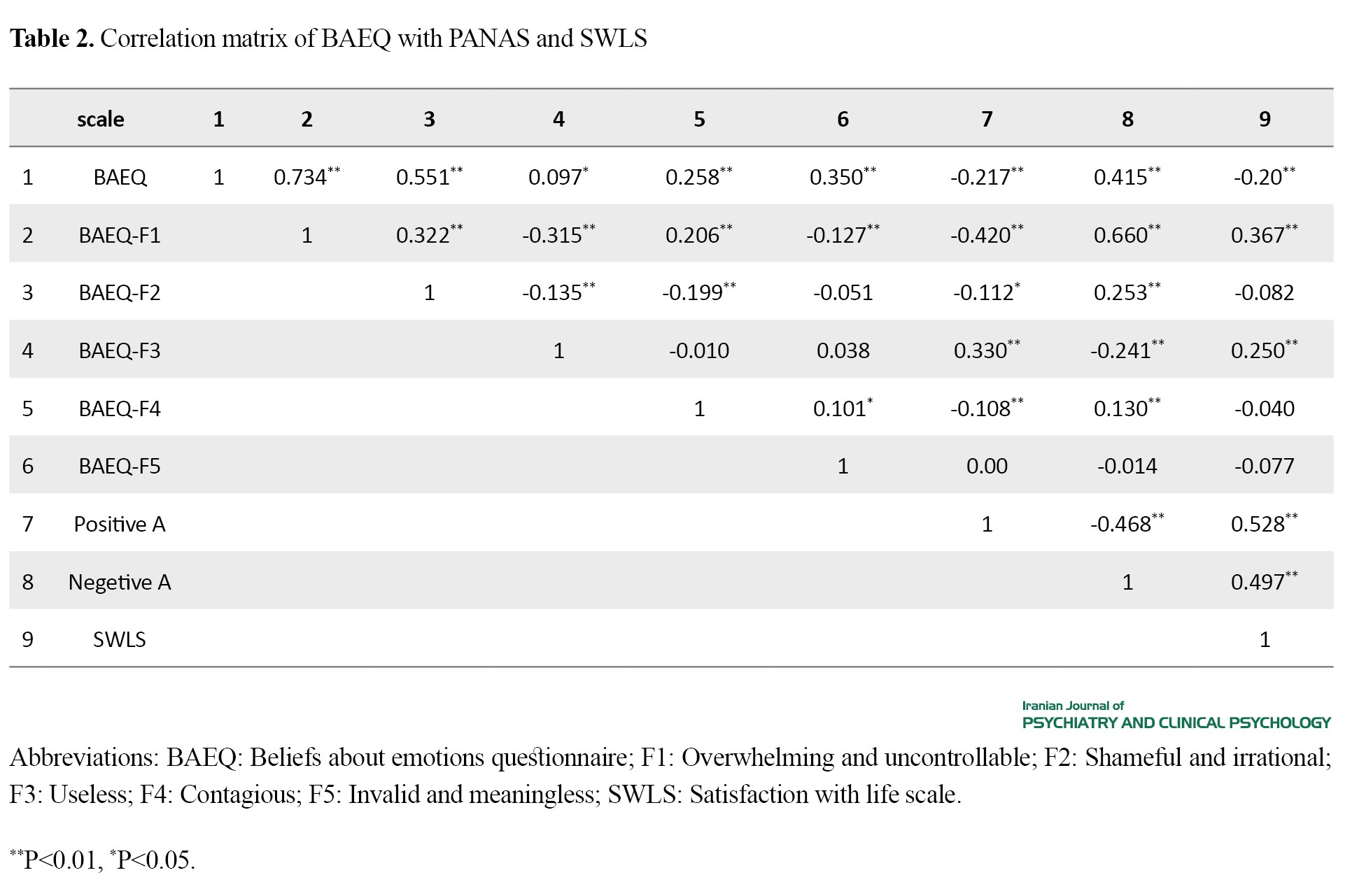

To examine convergent validity, the AVE was used. In the present study, the AVE value was estimated at 0.5. To assess criterion validity, as shown in Table 2, there is a significant correlation between the total score of BAEQ and the PANAS and SWLS.

These results confirm the convergent validity of the BAEQ.

To examine the reliability of the present questionnaire, composite reliability and internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha were used. According to the research findings, the composite reliability value was calculated as 0.949. Also, the Cronbach α for the present questionnaire was calculated as 0.75.

Conclusion

Emotional beliefs are defined as the beliefs that individuals hold about mental phenomena such as emotions [8]. Given the crucial role of emotional beliefs in psychological well-being, the present study aimed to investigate the psychometric properties of the BAEQ in the Iranian population. The results of the study indicated that the Persian version of BAEQ with five factors and 25 items possesses satisfactory validity and reliability in the general population. Therefore, we encourage future researchers to further investigate the psychometric properties of the BAEQ, taking into account the limitations identified in the present study, such as the lack of longitudinal data, convenience sampling, and non-clinical samples. In conclusion, researchers can confidently utilize the Persian version of the BAEQ in research studies and for evaluating the effectiveness of clinical interventions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.ZUMS.REC.1403.018). All participants gave written informed consent. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This study was funded by the Student Research Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Writing: Mobina Mohammadi; Writing, Data analysis, review & editing; Amirhossein Rasouli; Conceptualization and supervision; Seyedeh Elnaz Mousavi and Omid Saeid; Writing: Parisa Sarahi, Sahar Abbaszadeh, and Samaneh Shishechi; Final approval: All authorsConflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

Emotions are multifaceted, encompassing experiential, behavioral and physiological responses originating from the affective system [1]. They can be positive or negative, arising when stimuli are perceived as goal-relevant [2]. Emotion regulation is the process of monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotions for adaptive responding [3], is crucial for psychological well-being [4]. However, difficulties in emotion regulation can contribute to psychological disorders [5, 6]. Researchers are exploring how individuals’ beliefs about their emotions, nature, characteristics and function influence their regulation efforts [7].

Evidence suggests that beliefs about emotions significantly impact responses to challenges and opportunities [8], playing a key role in emotion regulation, psychopathology, and overall well-being [7, 9-14]. Negative beliefs (e.g. perceiving emotions as dangerous or uncontrollable) are linked to maladaptive strategies and increased risk of disorders [7, 15], while positive beliefs can foster adaptive strategies and improve mental health [16]. Understanding these beliefs can inform effective therapeutic interventions [17].

Existing measures of emotional beliefs often have limitations, such as focusing on a narrow range of beliefs or lacking cultural sensitivity [18]. The beliefs about emotions questionnaire (BAEQ), a comprehensive assessment developed by Manser et al. [19], requires validation across diverse populations. Given cultural and linguistic influences on emotional experience [22], validating the BAEQ, which has seen varying factor structures in different populations [9, 20], for the Iranian population is crucial, especially considering the prevalence of psychological disorders and the need for effective emotion regulation interventions in the country [21]. This study examines the psychometric properties and measurement invariance of a Persian version of the BAEQ, providing a valuable instrument for researchers and clinicians in Iran. This will enable a more accurate assessment of emotional beliefs and facilitate the development of culturally sensitive interventions to improve emotion regulation and psychological well-being.

Methods

This cross-sectional psychometric study was conducted with residents of Zanjan City, Iran. The inclusion criteria for this study were informed consent, minimum education level of eighth grade and age range of 18 to 50 years. The exclusion criterion was the participant’s desire to withdraw from the study and random responses to the items. After the translation and back-translation process, the study questionnaire, including the BAEQ, positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) and satisfaction with life scale (SWLS), was administered to the participants. The participants provided informed virtual consent before completing the questionnaire. The final sample consisted of 453 individuals. All participants were Iranian and were selected using a convenience sampling method.

Descriptive statistics (means and percentages) were used to analyze demographic information. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using principal component analysis to identify the underlying factor structure of the BAEQ. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test and the Bartlett test of sphericity were used to ensure the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the maximum likelihood method to evaluate the factor structure of the BAEQ.

To determine the invariance of the psychometric parameters of the BAEQ across genders (females vs males), measurement invariance was assessed. Internal consistency reliability was assessed using the Cronbach α and composite reliability. Additionally, convergent validity was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE) index, and criterion validity was assessed by examining the correlation of the instrument with the PANAS and the SWLS. The data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 27, for descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis, and AMOS software, version 24 for conformatory factor analysis.

Results

A total of 453 participants were included in this study, with 65.1% (n=295) being female and 34.9% (n=158) being male. The skewness and kurtosis of the variables revealed that all of them were within the range of (-2 to 2), indicating normality.

Exploratory factor analysis using the principal component analysis method and varimax rotation was used to examine the factor structure of the BAEQ. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value obtained was 0.85, indicating sampling adequacy. After performing factor analysis, the scree plot showed 11 factors with eigenvalues greater than one. In contrast, parallel analysis using Monte Carlo software suggested five factors.

The value of 0.4 was considered as the basis for item communality and items with a communality below this value were excluded from further analysis. Consequently, 18 items were removed. The results indicated five factors: Overwhelming and uncontrollable that explained 7.20% of the total variance with an eigenvalue of 6.045; shameful and irrational with 5.12% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 3.83; useless with 8.58% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 3.12; contagious with 6.56% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 1.77 and invalid and meaningless with 5.95% of the total variance and an eigenvalue of 1.51. Together, these five factors explained 54% of the total variance.

Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the five-factor model has good fit in the Iranian population (Table 1).

The results of the measurement invariance test for the five-factor model showed satisfactory fit indices based on Tucker-Lewis index, comparative fit index, and root mean square error of approximation for both male and female groups. Therefore, based on Chen’s recommendations [30], invariance is established for the five-factor model in both genders (Table 1).

To examine convergent validity, the AVE was used. In the present study, the AVE value was estimated at 0.5. To assess criterion validity, as shown in Table 2, there is a significant correlation between the total score of BAEQ and the PANAS and SWLS.

These results confirm the convergent validity of the BAEQ.

To examine the reliability of the present questionnaire, composite reliability and internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha were used. According to the research findings, the composite reliability value was calculated as 0.949. Also, the Cronbach α for the present questionnaire was calculated as 0.75.

Conclusion

Emotional beliefs are defined as the beliefs that individuals hold about mental phenomena such as emotions [8]. Given the crucial role of emotional beliefs in psychological well-being, the present study aimed to investigate the psychometric properties of the BAEQ in the Iranian population. The results of the study indicated that the Persian version of BAEQ with five factors and 25 items possesses satisfactory validity and reliability in the general population. Therefore, we encourage future researchers to further investigate the psychometric properties of the BAEQ, taking into account the limitations identified in the present study, such as the lack of longitudinal data, convenience sampling, and non-clinical samples. In conclusion, researchers can confidently utilize the Persian version of the BAEQ in research studies and for evaluating the effectiveness of clinical interventions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.ZUMS.REC.1403.018). All participants gave written informed consent. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This study was funded by the Student Research Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Writing: Mobina Mohammadi; Writing, Data analysis, review & editing; Amirhossein Rasouli; Conceptualization and supervision; Seyedeh Elnaz Mousavi and Omid Saeid; Writing: Parisa Sarahi, Sahar Abbaszadeh, and Samaneh Shishechi; Final approval: All authorsConflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Arbulu I, Salguero JM, Ramos-Cejudo J, Bjureberg J, Gross JJ. Emotion beliefs are associated with emotion regulation strategies and emotional distress. Current Psychology. 2023; 43:4364–73. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-023-04633-x]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry. 2015; 26(1):1-26. [DOI:10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781]

- Sheppes G, Suri G, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2015; 11:379-405. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112739] [PMID]

- Daros AR, Ruocco AC. Which emotion regulation strategies are most associated with trait emotion dysregulation? A transdiagnostic examination. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2021; 43(3):478-90. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-020-09864-x]

- Adolph D, Margraf J. Differential effects of trait-like emotion regulation use and situational emotion regulation ability across the affective and anxiety disorders spectrum: A transdiagnostic examination. Scientific Reports. 2024; 14(1):26642. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-76425-7] [PMID]

- Lotfi M, Amin M, Shiasy Y. [Comparing interpersonal and intrapersonal emotion regulation models in explaining depression and anxiety symptoms in college students (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2021; 27(3):288-301. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.27.2.2359.2]

- De Castella K, Goldin P, Jazaieri H, Ziv M, Dweck CS, Gross JJ. Beliefs about emotion: Links to emotion regulation, well-being, and psychological distress. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2013; 35(6):497-505. [DOI:10.1080/01973533.2013.840632]

- Petrova K, Zielke JN, Mehta A, Gross JJ. Occurrent beliefs about emotions predict emotion regulation in everyday life. Emotion. 2024; 24(4):992-1002. [DOI:10.1037/emo0001317] [PMID]

- Strodl E, Hubert M, Cooper M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Revised Beliefs About Emotions Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2023; 30(6):1471-81. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2889] [PMID]

- Ford BQ, Gross JJ. Why beliefs about emotion matter: An emotion-regulation perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2019; 28(1):74-81. [DOI:10.1177/0963721418806697]

- De Castella K, Platow MJ, Tamir M, Gross JJ. Beliefs about emotion: Implications for avoidance-based emotion regulation and psychological health. Cognition and Emotion. 2018; 32(4):773-95. [DOI:10.1080/02699931.2017.1353485] [PMID]

- Kneeland ET, Dovidio JF. Emotion malleability beliefs and coping with the college transition. Emotion. 2020; 20(3):452-61.[DOI:10.1037/emo0000559] [PMID]

- Hong EJ, Kangas M. The relationship between beliefs about emotions and emotion regulation: A systematic review. Behaviour Change. 2022; 39(4):205-34. [DOI:10.1017/bec.2021.23]

- Becerra R, Naragon-Gainey K, Gross JJ, Ohan J, Preece DA. Beliefs about emotions: Latent structure and links with emotion regulation and psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2024; 16:100728. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadr.2024.100728]

- Somerville MP, MacIntyre H, Harrison A, Mauss IB. Emotion controllability beliefs and young people’s anxiety and depression symptoms: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review. 2024; 9(1):33-51. [DOI:10.1007/s40894-023-00213-z] [PMID]

- Kneeland ET, Dovidio JF, Joormann J, Clark MS. Emotion malleability beliefs, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: Integrating affective and clinical science. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016; 45:81-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.008] [PMID]

- Kimhy D, Vakhrusheva J, Jobson-Ahmed L, Tarrier N, Malaspina D, Gross JJ. Emotion awareness and regulation in individuals with schizophrenia: Implications for social functioning. Psychiatry Research. 2012; 200(2):193-201. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.029] [PMID]

- Becerra R, Preece DA, Gross JJ. Assessing beliefs about emotions: Development and validation of the Emotion Beliefs Questionnaire. Plos One. 2020; 15(4):e0231395. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0231395] [PMID]

- Manser R, Cooper M, Trefusis J. Beliefs about emotions as a metacognitive construct: Initial development of a self-report questionnaire measure and preliminary investigation in relation to emotion regulation. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2012; 19(3):235-46. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.745] [PMID]

- Koç MS, Uzun B. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Beliefs About Emotions Questionnaire (BAEQ) and a preliminary investigation in relation to emotion regulation. Cognition, Brain, Behavior. 2022; 26(1):67-88. [Link]

- Taheri Mirghaed M, Abolghasem Gorji H, Panahi S. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020; 11:21. [DOI:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_510_18] [PMID]

- Prass MA, Bywater AR, Schreier BA. Advice in psychotherapy: Ethical, clinical, and cultural considerations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2024; 55(6):493–501. [DOI:10.1037/pro0000596]

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000; 25(24):3186-91. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014] [PMID]

- Bentler PM, Chou CP. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research. 1987; 16(1):78-117. [DOI:10.1177/0049124187016001004]

- Anthoine E, Moret L, Regnault A, Sébille V, Hardouin JB. Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2014; 12:176. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-014-0176-2] [PMID]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988; 54(6):1063-70. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063] [PMID]

- Sharifi HP, Bashardoust S, Emami Pour S. [Psychometric properties of positive and negative affect (Panas) (Persian)]. Journla of Psychological Researches. 2012; 4(13):17-27. [Link]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985; 49(1):71-5. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13] [PMID]

- Arrindell WA, Checa I, Espejo B, Chen IH, Carrozzino D, Vu-Bich P, et al. Measurement Invariance and Construct Validity of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) in community volunteers in Vietnam. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3460. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19063460] [PMID]

- Fallahi Khesht Masjedi M, Pasandideh MM. [Psychometric properties of satisfaction with life scale in psychiatric patients (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2016; 22(2):147-58. [Link]

- Zhang X, Wu H. Investigating structural model fit evaluation. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2024; 31(5):863-81. [DOI:10.1080/10705511.2024.2350023]

- Schmitt N, Kuljanin G. Measurement invariance: Review of practice and implications. Human Resource Management Review. 2008; 18(4):210-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.03.003]

- Chen FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007; 14(3):464-504. [DOI:10.1080/10705510701301834]

- Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review. 2016; 41:71-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004] [PMID]

- Glisenti K, Strodl E, King R. The role of beliefs about emotions in emotion-focused therapy for binge-eating disorder. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2023; 53(2):117-24. [DOI:10.1007/s10879-022-09555-6]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2024/07/20 | Accepted: 2024/11/27 | Published: 2024/07/31

Received: 2024/07/20 | Accepted: 2024/11/27 | Published: 2024/07/31

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |