Thu, Jan 29, 2026

| فارسی

Volume 31, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2025)

IJPCP 2025, 31(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Donyavi V, Rahnejat A M, Haghi A, Mohammadinia S, Jafari A. Planning and Implementing the Program of Assess, Intervene, and Monitor for Suicide Prevention Among Iranian Soldiers: An Action Research Study. IJPCP 2025; 31 (1)

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4150-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4150-en.html

Vahid Donyavi1

, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat2

, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat2

, Asghar Haghi3

, Asghar Haghi3

, Soodabeh Mohammadinia4

, Soodabeh Mohammadinia4

, Amirhossein Jafari5

, Amirhossein Jafari5

, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat2

, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat2

, Asghar Haghi3

, Asghar Haghi3

, Soodabeh Mohammadinia4

, Soodabeh Mohammadinia4

, Amirhossein Jafari5

, Amirhossein Jafari5

1- Department of Psychiatry, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Cognitive Science Research Center, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- MA in Counseling, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- MA in Clinical Psychology, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Tehran, Iran. ,ahjafarim@sina.tums.ac.ir

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Cognitive Science Research Center, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- MA in Counseling, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- MA in Clinical Psychology, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 6752 kb]

(962 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1286 Views)

Full-Text: (1534 Views)

Introduction

Suicide is one of the most important causes of death worldwide. It is the tenth leading cause of death in all ages and third among persons 15-24 years of age [1]. In military settings, suicide ideation is more prevalent than in the general population [2]. Furthermore, suicide in soldiers is of great importance from different aspects, this issue increases the need to implement suicide prevention programs. There are previous experiences with suicide prevention. One of them is the assessment, intervention, and monitoring for suicide prevention (AIM-SP) model, which has been successful. A model that provides best practice AIM-SP is evidence-based in suicide prevention and can be applied in a wide range of care settings [3]. This model was utilized in more than 170 clinics in New York State, USA, for nearly 80000 patients [4]. In this study, we intended to plan, implement, and evaluate a suicide prevention program named HAYAT among army soldiers, based on the AIM-SP model. This study assesses this suicide prevention service by qualitative and quantitative methods.

Methods

In this action research study, for the first step, we performed a situation analysis by observing, evaluating the processes, analysis of statistics statistical analysis and needs assessment. These data were discussed in a group discussion by the expert panel (including five key persons and key professionals in mental health) to provide an appropriate solution for suicide prevention. Based on the AIM-SP model and according to group discussion, the framework of the suicide prevention program was prepared. In this regard, we prepared an executive protocol that declared duties in three sections, including assessment, intervention, and monitoring for each client with high suicide risk, moderate suicide risk, low suicide risk, and without significant suicide risk. The suicide risk level was determined using the Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). At the first session, the C-SSRS asks about suicidal thoughts and behaviors in lifetime, especially the past three months. in subsequent visits, the “since last contact form” was fulfilled. In executive protocol, for each suicide level, essential interventions have been declared, including means restriction, safety planning, referral to psychiatry hospital, psychoeducation for patient and family, education of problem-solving, and informing the superior. In the monitoring section, frequent in-person visits or telephone follow-ups, according to suicide risk level, were suggested.

Also, we performed a brief training course and several advocacy sessions before the service began. This program was launched for 1 year in a barracks with 338 soldiers as a pilot period and thereafter was evaluated by quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data was compared with a similar barrack. Also, for the determination of suicide risk triage accuracy, we employed the Beck scale for suicidal ideation, the Beck hopelessness scale, and general health questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) besides C-SSRS. Correlation coefficients were calculated using the SPSS software, version 23.

Results

The result of this study revealed that suicide risk estimation in this program is more accurate compared with conventional methods. Compared to the conventional method, suicide risk estimation in this program is more accurate Also, this program had feasibility, appropriateness, acceptability, and efficacy for suicide prevention, based on stakeholders’ opinion. In the pilot implementation period, the rate of patient referral to the psychiatry center was more than the control barrack (9.1% vs 1.9%). Conventional tool for suicide risk detection in Iran army soldiers was done based on GHQ-28, only one time at the beginning of recruitment; but in this service, we utilized C-SSRS at least one time each three months. by correlation of these two instruments with Beck scale suicidal ideation, it was revealed that suicide risk assessment by C-SSRS, as a semi-structured tool, has more accuracy than the conventional method using GHQ-28.

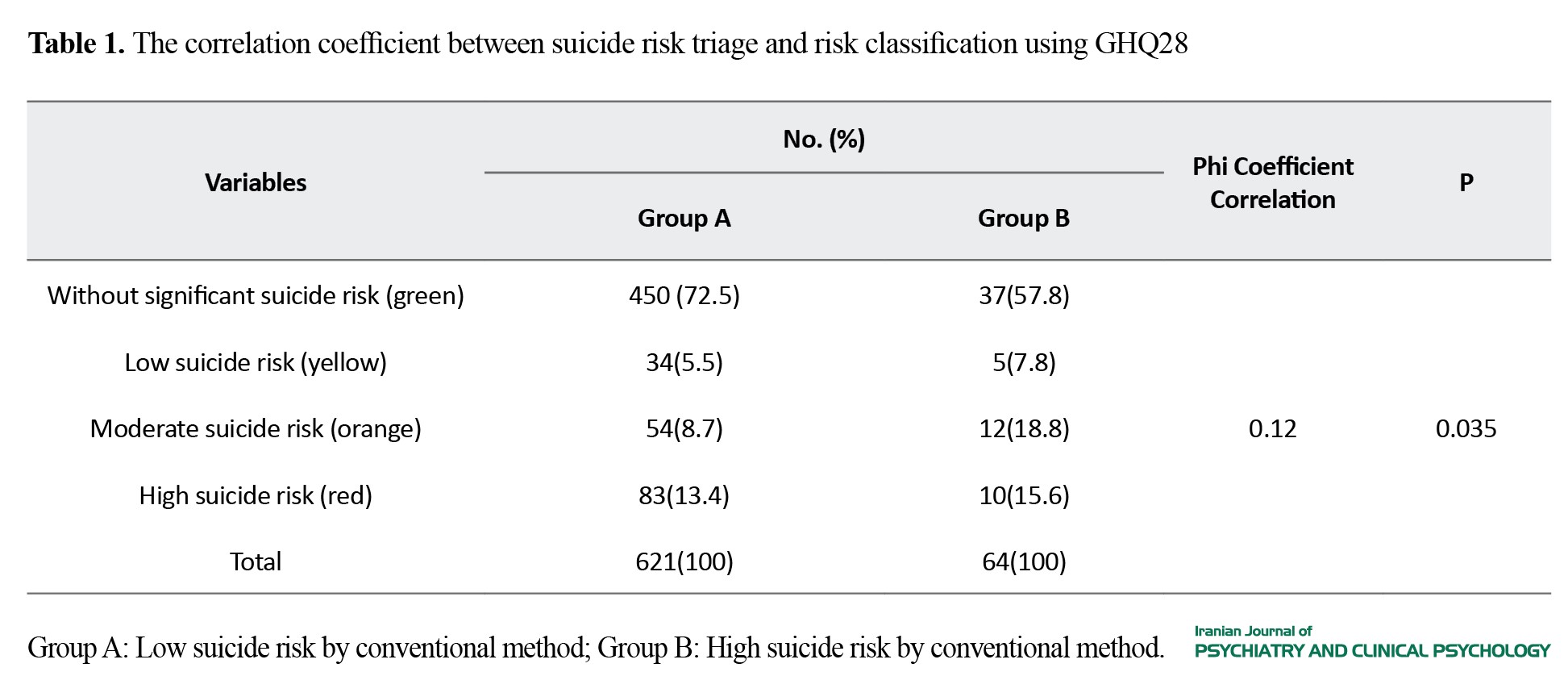

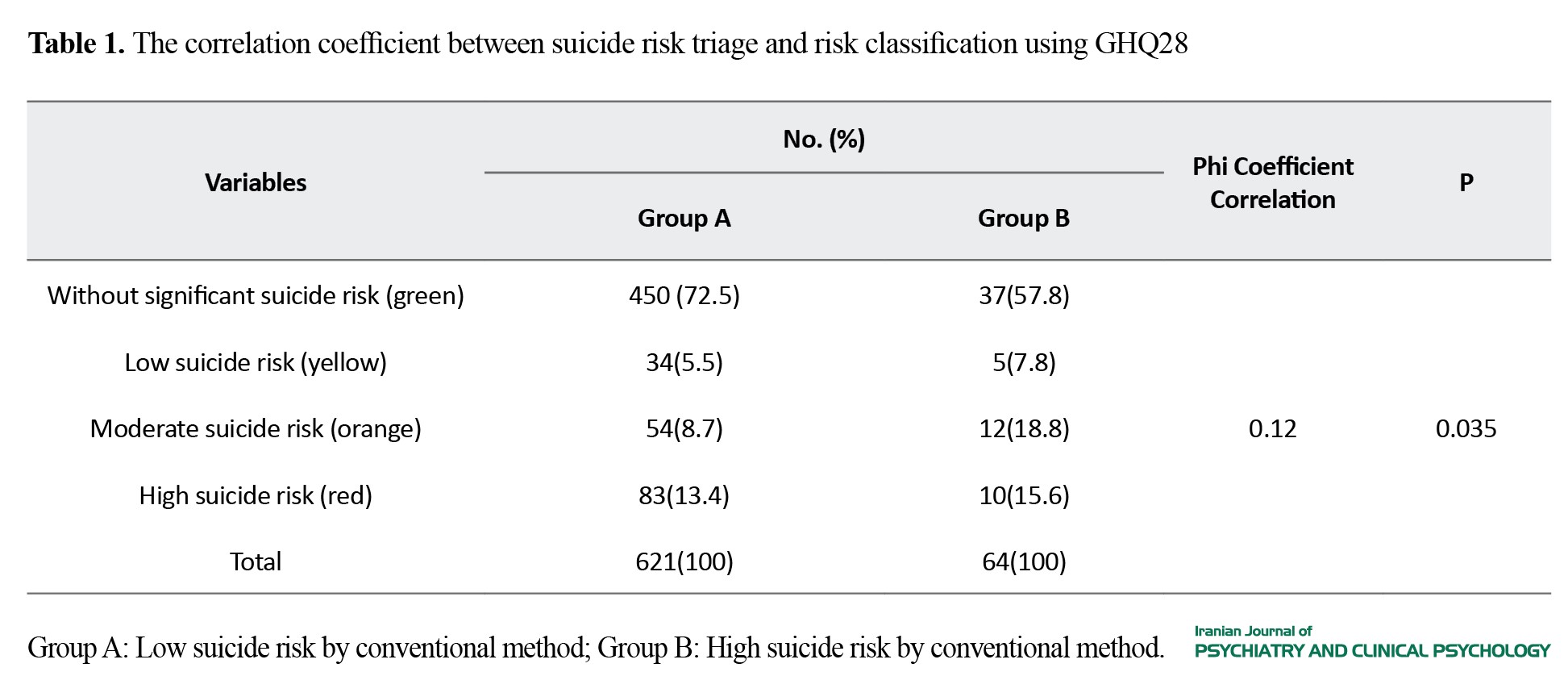

In this study, ordinary suicide risk classification that persons were categorized in two group A (low suicide risk) and group B (high suicide risk) categories, was evaluated. The Phi correlation coefficient between this method and suicide risk triage by C-SSRS was 0.12, which means these two methods have a low correlation. Considering that both the Beck scale for suicidal ideation and the Beck hopelessness scale have a high association with C-SSRS but not with GHQ28, suicide risk assessment by C-SSRS is more reliable than the conventional method (Table 1).

Conclusion

The suicide prevention program, based on the AIM-SP model, provided that it is adapted to the military setting, is suitable for suicide prevention in soldiers. Considering the presence of consultation offices in each army barrack, the implementation of this model is feasible. C-SSRS, as a semi-structured instrument for suicide prevention, can be used in this model to determine suicide risk triage. These data showed that suicide risk assessment using the C-SSRS tool is more accurate than the conventional method that was been performed by GHQ-28.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of AJA University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.AJAUMS.REC.1399.274). All participants declared their written informed consent. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Vahid Donyavi, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat, and Amirhossein Jafari; investigation: Vahid Donyavi, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat, Asghar Haghi, and Amirhossein Jafari; draft preparation: Amirhossein Jafari; supervision and data Analysis: Amirhossein Jafari and Soodabeh Mohammadinia; design, methodology, Review & Editing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

Suicide is one of the most important causes of death worldwide. It is the tenth leading cause of death in all ages and third among persons 15-24 years of age [1]. In military settings, suicide ideation is more prevalent than in the general population [2]. Furthermore, suicide in soldiers is of great importance from different aspects, this issue increases the need to implement suicide prevention programs. There are previous experiences with suicide prevention. One of them is the assessment, intervention, and monitoring for suicide prevention (AIM-SP) model, which has been successful. A model that provides best practice AIM-SP is evidence-based in suicide prevention and can be applied in a wide range of care settings [3]. This model was utilized in more than 170 clinics in New York State, USA, for nearly 80000 patients [4]. In this study, we intended to plan, implement, and evaluate a suicide prevention program named HAYAT among army soldiers, based on the AIM-SP model. This study assesses this suicide prevention service by qualitative and quantitative methods.

Methods

In this action research study, for the first step, we performed a situation analysis by observing, evaluating the processes, analysis of statistics statistical analysis and needs assessment. These data were discussed in a group discussion by the expert panel (including five key persons and key professionals in mental health) to provide an appropriate solution for suicide prevention. Based on the AIM-SP model and according to group discussion, the framework of the suicide prevention program was prepared. In this regard, we prepared an executive protocol that declared duties in three sections, including assessment, intervention, and monitoring for each client with high suicide risk, moderate suicide risk, low suicide risk, and without significant suicide risk. The suicide risk level was determined using the Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). At the first session, the C-SSRS asks about suicidal thoughts and behaviors in lifetime, especially the past three months. in subsequent visits, the “since last contact form” was fulfilled. In executive protocol, for each suicide level, essential interventions have been declared, including means restriction, safety planning, referral to psychiatry hospital, psychoeducation for patient and family, education of problem-solving, and informing the superior. In the monitoring section, frequent in-person visits or telephone follow-ups, according to suicide risk level, were suggested.

Also, we performed a brief training course and several advocacy sessions before the service began. This program was launched for 1 year in a barracks with 338 soldiers as a pilot period and thereafter was evaluated by quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data was compared with a similar barrack. Also, for the determination of suicide risk triage accuracy, we employed the Beck scale for suicidal ideation, the Beck hopelessness scale, and general health questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) besides C-SSRS. Correlation coefficients were calculated using the SPSS software, version 23.

Results

The result of this study revealed that suicide risk estimation in this program is more accurate compared with conventional methods. Compared to the conventional method, suicide risk estimation in this program is more accurate Also, this program had feasibility, appropriateness, acceptability, and efficacy for suicide prevention, based on stakeholders’ opinion. In the pilot implementation period, the rate of patient referral to the psychiatry center was more than the control barrack (9.1% vs 1.9%). Conventional tool for suicide risk detection in Iran army soldiers was done based on GHQ-28, only one time at the beginning of recruitment; but in this service, we utilized C-SSRS at least one time each three months. by correlation of these two instruments with Beck scale suicidal ideation, it was revealed that suicide risk assessment by C-SSRS, as a semi-structured tool, has more accuracy than the conventional method using GHQ-28.

In this study, ordinary suicide risk classification that persons were categorized in two group A (low suicide risk) and group B (high suicide risk) categories, was evaluated. The Phi correlation coefficient between this method and suicide risk triage by C-SSRS was 0.12, which means these two methods have a low correlation. Considering that both the Beck scale for suicidal ideation and the Beck hopelessness scale have a high association with C-SSRS but not with GHQ28, suicide risk assessment by C-SSRS is more reliable than the conventional method (Table 1).

Conclusion

The suicide prevention program, based on the AIM-SP model, provided that it is adapted to the military setting, is suitable for suicide prevention in soldiers. Considering the presence of consultation offices in each army barrack, the implementation of this model is feasible. C-SSRS, as a semi-structured instrument for suicide prevention, can be used in this model to determine suicide risk triage. These data showed that suicide risk assessment using the C-SSRS tool is more accurate than the conventional method that was been performed by GHQ-28.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of AJA University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.AJAUMS.REC.1399.274). All participants declared their written informed consent. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Vahid Donyavi, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat, and Amirhossein Jafari; investigation: Vahid Donyavi, Amir Mohsen Rahnejat, Asghar Haghi, and Amirhossein Jafari; draft preparation: Amirhossein Jafari; supervision and data Analysis: Amirhossein Jafari and Soodabeh Mohammadinia; design, methodology, Review & Editing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Pennsylvania: lippincott Williams & wilkins; 2017. [Link]

- Moradi Y, Dowran B, Sepandi M. The global prevalence of depression, suicide ideation, and attempts in the military forces: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of cross sectional studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2021; 21(1):510. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-021-03526-2] [PMID]

- Nock MK, Stein MB, Heeringa SG, Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014; 71(5):514-22. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.30] [PMID]

- Carr JR, Hoge CW, Gardner J, Potter R. Suicide surveillance in the US Military-reporting and classification biases in rate calculations. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004; 34(3):233-41. [DOI:10.1521/suli.34.3.233.42785] [PMID]

- Bakhtar M, Rezaeian M. A survey on the suicidal behavior in Iranian military forces: A systematic review study. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. 2018; 16(11):1065-80. [Link]

- Soltaninejad A, Ashtiani A, Ahmadi K, Yahaghi E, Nikmorad A, Karimi R, et al. [Structural equation model of borderline personality disorder, emotion-focused coping styles, impulsivity and suicide ideation in soldiers (Persian)]. Journal of Police Medicine. 2013; 1(3):176-82. [Link]

- Khademi A, Moradi S, Soleymani G. Analytical review of suicide by firearms in Iran. Iranian Journal of Forensic Medicine. 2004; 10(3):80-7. [Link]

- Nouri R, Fathi-Ashtiani A, Salimi SH, Soltani Nejad A. Effective factors of suicide in soldiers of a military force. Journal of Military Medicine. 2012; 14(2):99-103. [Link]

- Landes SD, Wilmoth JM, London AS, Landes AT. Risk factors explaining military deaths from suicide, 2008-2017:A Latent Class Analysis. Armed Forces and Society. 2023; 49(1):115-37. [DOI:10.1177/0095327X211046976] [PMID]

- Wasserman D. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2020. [DOI:10.1093/med/9780198834441.001.0001]

- Brodsky BS, Spruch-Feiner A, Stanley B. The zero suicide model: Applying evidence-based suicide prevention practices to clinical care. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018; 9:33. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00033] [PMID]

- Labouliere CD, Vasan P, Kramer A, Brown G, Green K, Rahman M, et al. “Zero Suicide”-A model for reducing suicide in United States behavioral healthcare. Suicidologi. 2018; 23(1):22-30. [PMID]

- Stanley B, Labouliere CD, Brown GK, Green KL, Galfalvy HC, Finnerty MT, et al. Zero suicide implementation-effectiveness trial study protocol in outpatient behavioral health using the A-I-M suicide prevention model. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2021; 100:106224. [DOI:10.1016/j.cct.2020.106224] [PMID]

- Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): Classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007; 164(7):1035-43. [DOI:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1035] [PMID]

- Andreotti ET, Ipuchima JR, Cazella SC, Beria P, Bortoncello CF, Silveira RC, et al. Instruments to assess suicide risk: A systematic review. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2020; 42(3):276-81. [DOI:10.1590/2237-6089-2019-0092] [PMID]

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Suicidal Ideation and Behavior: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials. Maryland: Food and Drug Administration; 2012. [Link]

- Bjureberg J, Dahlin M, Carlborg A, Edberg H, Haglund A, Runeson B. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale Screen Version: Initial screening for suicide risk in a psychiatric emergency department. Psychological Medicine. 2021; 52(16):1-9. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291721000751] [PMID]

- Conway PM, Erlangsen A, Teasdale TW, Jakobsen IS, Larsen KJ. Predictive validity of the columbia-suicide severity rating scale for short-term suicidal behavior: A Danish study of adolescents at a high risk of suicide. Archives of Suicide Research. 2017; 21(3):455-69. [DOI:10.1080/13811118.2016.1222318] [PMID]

- Matarazzo BB, Brown GK, Stanley B, Forster JE, Billera M, Currier GW, et al. Predictive Validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale among a Cohort of At-risk Veterans. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2019; 49(5):1255-65. [DOI:10.1111/sltb.12515] [PMID]

- Peterson K, Anderson J, Bourne D. VA Evidence Brief: Suicide prevention in veterans. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2018. [PMID]

- Pumariega AJ, Good K, Posner K, Millsaps U, Romig B, Stavarski D, et al. Systematic suicide screening in a general hospital setting: Process and initial results. World Social Psychiatry. 2020; 2(1):31-42. [DOI:10.4103/WSP.WSP_26_19]

- Jafari A, Rahnejat A, Hooshyari Z, Taghva A, Ghasemzadeh MR, Donyavi V. Psychometric properties of a Persian Version of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) in Iranian Soldiers. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2024; 1-11. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v19i3.15831]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011; 38(2):65-76. [DOI:10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7] [PMID]

- Bingham AJ. From data management to actionable findings: A five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2023; 22:16094069231183620. [DOI:10.1177/16094069231183620]

- Large MM. The role of prediction in suicide prevention. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2018; 20(3):197-205. [DOI:10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.3/mlarge]

- Posner K, Subramany R, Amira L, John Mann J. From uniform definitions to prediction of risk: The Columbia suicide severity rating scale approach to suicide risk assessment. In: Cannon K, Hudzik T, editor. Suicide: Phenomenology and neurobiology. Cham: Springer; 2014. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-09964-4_4]

- Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Real-time assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2018; 22:33-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.026] [PMID]

- Hughes JL, Horowitz LM, Ackerman JP, Adrian MC, Campo JV, Bridge JA. Suicide in young people: Screening, risk assessment, and intervention. BMJ. 2023; 381:e070630. [DOI:10.1136/bmj-2022-070630] [PMID]

- Gutierrez PM, Watkins R, Collura D. Suicide risk screening in an urban high school. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004; 34(4):421-8. [DOI:10.1521/suli.34.4.421.53741] [PMID]

- Hallfors D, Brodish PH, Khatapoush S, Sanchez V, Cho H, Steckler A. Feasibility of screening adolescents for suicide risk in “real-world” high school settings. American Journal of Public Health. 2006; 96(2):282-7. [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2004.057281] [PMID]

- Statements Q. Va/Dod clinical practice guideline for assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide.2013. [Link]

- Nordentoft M. Crucial elements in suicide prevention strategies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2011; 35(4):848-53. [DOI:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.038] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2024/04/7 | Accepted: 2025/01/1 | Published: 2024/07/31

Received: 2024/04/7 | Accepted: 2025/01/1 | Published: 2024/07/31

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |