Tue, Jul 1, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 29, Issue 4 (Winter 2024)

IJPCP 2024, 29(4): 418-437 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Masoumian S, Mehravin E, Ghadyani Z, Moradi N, Sobhani S S, Ashouri A. The Group-based Compassion-focused Intervention on Academic Procrastination, Anxiety, and Quality of Life of University Students: A Controlled Trial With 3-month Follow-up. IJPCP 2024; 29 (4) :418-437

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4046-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4046-en.html

Samira Masoumian1

, Esfandiar Mehravin2

, Esfandiar Mehravin2

, Zahra Ghadyani2

, Zahra Ghadyani2

, Neda Moradi2

, Neda Moradi2

, Samira Shams Sobhani2

, Samira Shams Sobhani2

, Ahmad Ashouri3

, Ahmad Ashouri3

, Esfandiar Mehravin2

, Esfandiar Mehravin2

, Zahra Ghadyani2

, Zahra Ghadyani2

, Neda Moradi2

, Neda Moradi2

, Samira Shams Sobhani2

, Samira Shams Sobhani2

, Ahmad Ashouri3

, Ahmad Ashouri3

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Mental Health Research Center, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ahmad.ashouri@gmail.com

2- Mental Health Research Center, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 6816 kb]

(721 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1414 Views)

Full-Text: (573 Views)

Introduction

Procrastination is “the voluntary delay of an intended, necessary, and or personally important activity, despite expecting potential negative consequences that outweigh the positive consequences of the delay” [1]. One specific form of procrastination is academic procrastination. This type is restricted to the tasks and activities related to learning and studying [2]. Academic procrastination is a common problem among students. According to some reports, about 70% of students identify themselves as procrastinators in areas like writing papers and reading for exams. Instead, they tend to engage in more pleasant activities [3]. Procrastination can have functions such as failure avoidance and protecting oneself against being hurt. That is why procrastination is so common among students [4]. Procrastination has many adverse consequences. It negatively affects subjective wellbeing [5], academic achievement and self-efficacy [6], and financial and occupational issues [7]. Procrastination is also associated with low self-compassion [8], low mindfulness [9], emotion regulation difficulties [10], depression [11], and anxiety [12].

Research has also shown that self-compassion can act as a mediator between stress and depression [8]. It has been suggested that for some students, procrastination can act as an emotion regulation strategy that provides instantaneous emotional relief [13, 14]. According to Gilbert [15], an imbalance between the neurocognitive processes underlying emotion regulation, especially the inadequate activity of the system responsible for producing emotional calmness (the soothing system), elucidates why people usually do not feel emotionally relaxed, even if they are helped in traditional treatments to change their thoughts and behaviors.

Therefore, Gilbert designed a treatment program (called compassion-focused therapy [CFT]) to activate the soothing system. From an evolutionary perspective, Gilbert explains how humans have developed three emotion regulation systems: Threat, motivational, and soothing. The threat system, related to harm avoidance behaviors, works by creating emotions such as anger and fear. The motivational or drive system, related to reward approach behaviors, creates emotions such as ambition and sexual desire. Finally, the soothing system is related to social mentality and the attachment system and works by creating emotions, such as sympathy and compassion. According to Gilbert, the threat system is highly developed in people who often experience negative emotions, and the soothing system is underdeveloped [15-18]. It can be assumed that the threat system in procrastinators is hyperactive, and their soothing system is underactive. Thus, they prefer to postpone their tasks to eliminate unpleasant feelings when doing tasks. Accordingly, one of the mechanisms through which CFT can help procrastinators is balancing their three emotion regulation systems. Creating a balance between the three emotion regulation systems, people with more effective emotion regulation do not have to postpone their tasks to get rid of unpleasant feelings when faced with tasks that require hard work.

According to what was discussed and previous studies, we conducted this research with the assumption that group CFT can significantly improve academic procrastination, anxiety, and quality of life (QoL) in university students.

Methods

This research is an experimental study of clinical trial type. The statistical population of this study included all students of Iran University of Medical Sciences. Using convenience sampling, 40 students were selected as a statistical sample and then randomly divided into control and experimental groups. The inclusion criteria were being 18 to 45 years old, obtaining a minimum score on the procrastination questionnaire, not suffering from clinical disorders such as psychotic disorders or substance use disorder based on the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 clinical disorders (SCID-5-CV), lacking a severe personality disorder based on Milon such as schizotypal, paranoid, and schizoid based on the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 personality disorders (SCID-5-PD), and being willing to cooperate in the therapy sessions. The experimental group received eight 120-minute sessions of group compassion-focused therapy once a week, while the control group received no intervention. The study tools included a demographic questionnaire; academic procrastination questionnaire; depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21); and personal wellbeing index-adult (PWI-A). The eight-session program used for the experimental group was designed according to the Gilbert guide [31].

Research tools

Demographic questionnaire

A researcher-made questionnaire was used to obtain demographic information of the students, which includes items such as age, sex, marital status, employment status, educational status, previous history and duration of psychiatric and psychological disorders (clinical and personality disorders), and received treatments (pharmacological and non-pharmacological).

Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders-clinical version (SCID-5-CV)

This tool is a semi-structured clinical and diagnostic interview developed by First et al. in 2015 to assess clinical disorders [22], including anxiety and mood disorders, psychosis, and substance abuse. Each disorder’s level of damage and severity can be evaluated using this tool. The validity and reliability of this tool have been examined and confirmed [23].

Structured clinical interview for personality disorders DSM-5 (SCID-5-PD)

In 2015, First et al. designed a new version of the structured diagnostic interview based on DSM-5 to evaluate 10 personality disorders [24]. The results of the study confirm its validity and reliability. In this study, in diagnoses related to obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizotypal, schizoid, dramatic, narcissistic, borderline, and antisocial personality disorder, the kappa value is higher than 0.4. In diagnoses related to avoidant, dependent, and other personality disorders, the kappa value was lower than 0.4 [25].

The academic procrastination scale

This scale was developed in 1984 by Solomon and Rothblum to assess student procrastination and has 27 items and 5 subscales. Responders can show their agreement rate with each item by choosing one of the options: Rarely, sometimes, or always [26].

Depression, anxiety and stress scale-21 (DASS-21)

The short form has 21 items with 3 subscales (depression, anxiety, and stress). The participants should rate the intensity (frequency) of the symptoms they have experienced over the past week using a 4-point scale (between 0 and 3). This scale has been confirmed by factor analysis, and the results indicate the convergent and divergent validity of this scale. The scale validity was also studied using the test re-test method, confirming its validity in general Iranian society [29].

Personal wellbeing index-adult (PWI-A)

PWI-A contains 7 items of satisfaction, each related to an area of QoL, including material level of life, health, personal relationships, safety, achievements in life, position, and social security in the future. Each scale question is scored between 0 and 10. In Iran, the research findings showed that the scale has good reliability based on the whole scale alpha coefficient (0.89) and correlation coefficient of its re-test (0.79). Also, the obtained correlation coefficients indicate the convergent validity of the scale with similar instruments [30].

Results

Using the chi-square test to compare the experimental and control groups in variables such as gender, occupation, marital status, educational status, previous history of physical and psychological illness, and history of referring and receiving pharmaceutical and non-pharmacological treatments showed no statistically significant differences. Therefore, the two studied groups are comparable in terms of these variables.

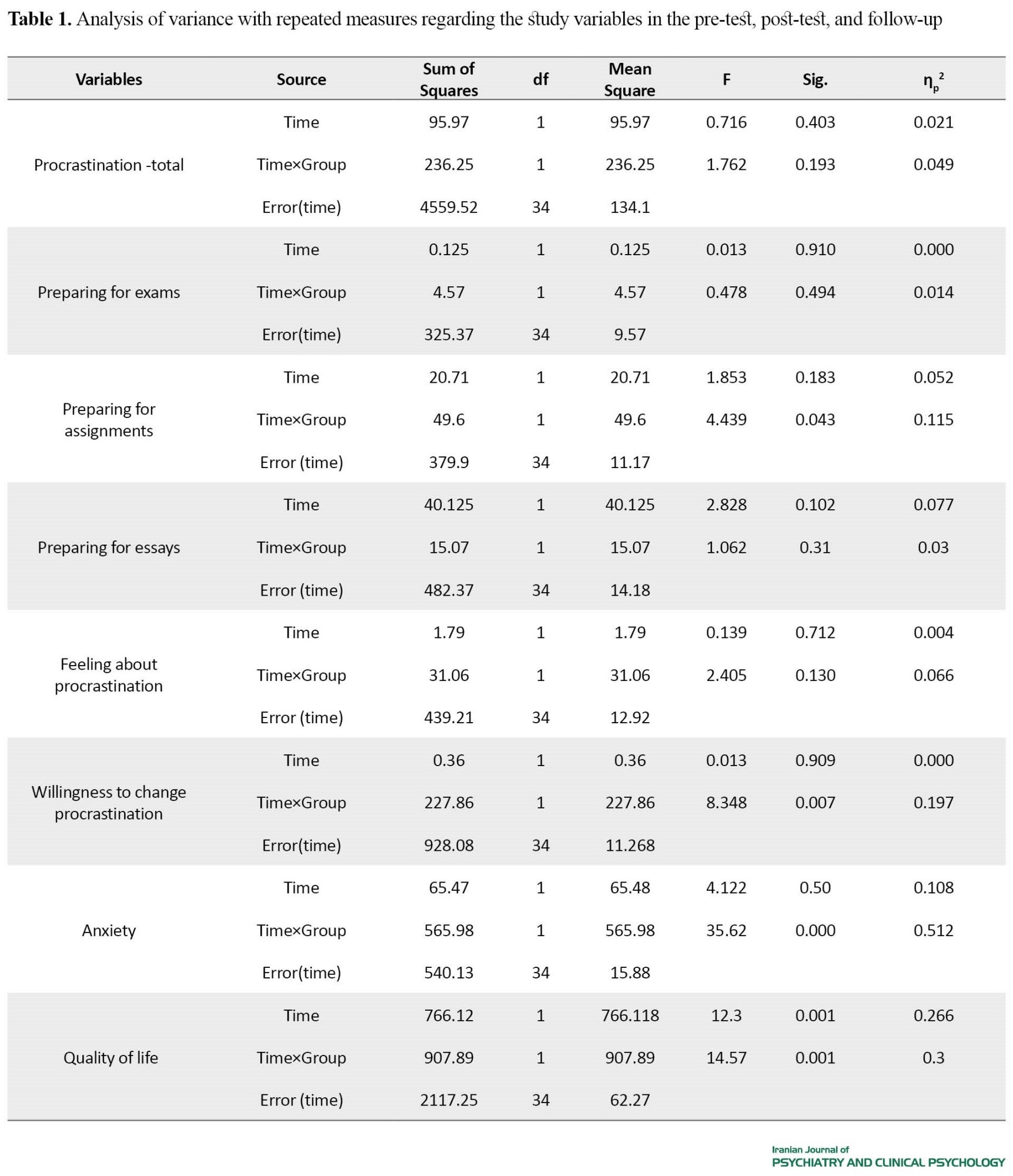

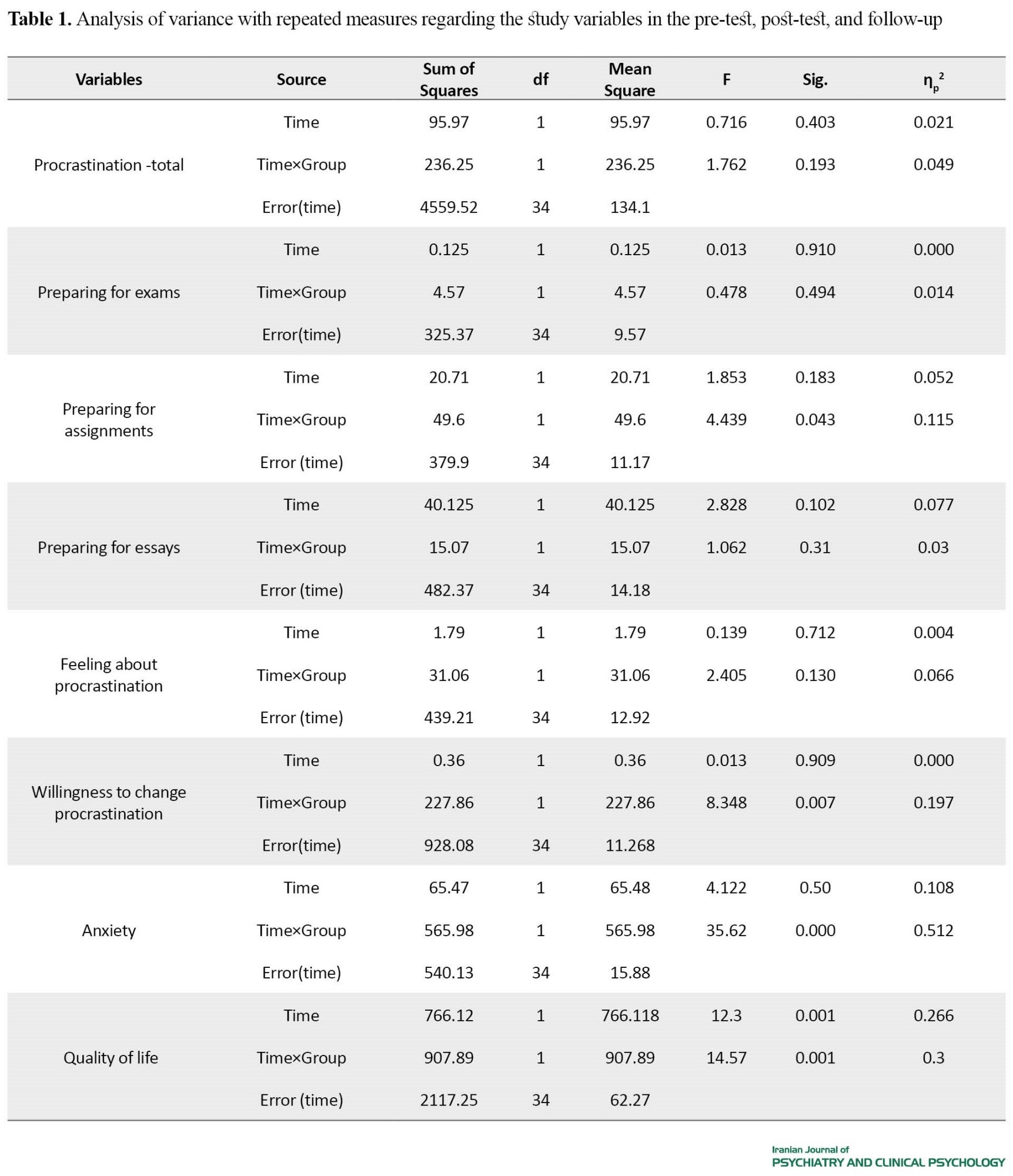

Now, the experimental and control groups’ changes in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages are investigated (Table 1).

According to the principle of normality and sphericity of the studied variables, the GLM repeated measures analysis of variance (GLMRM) was used.

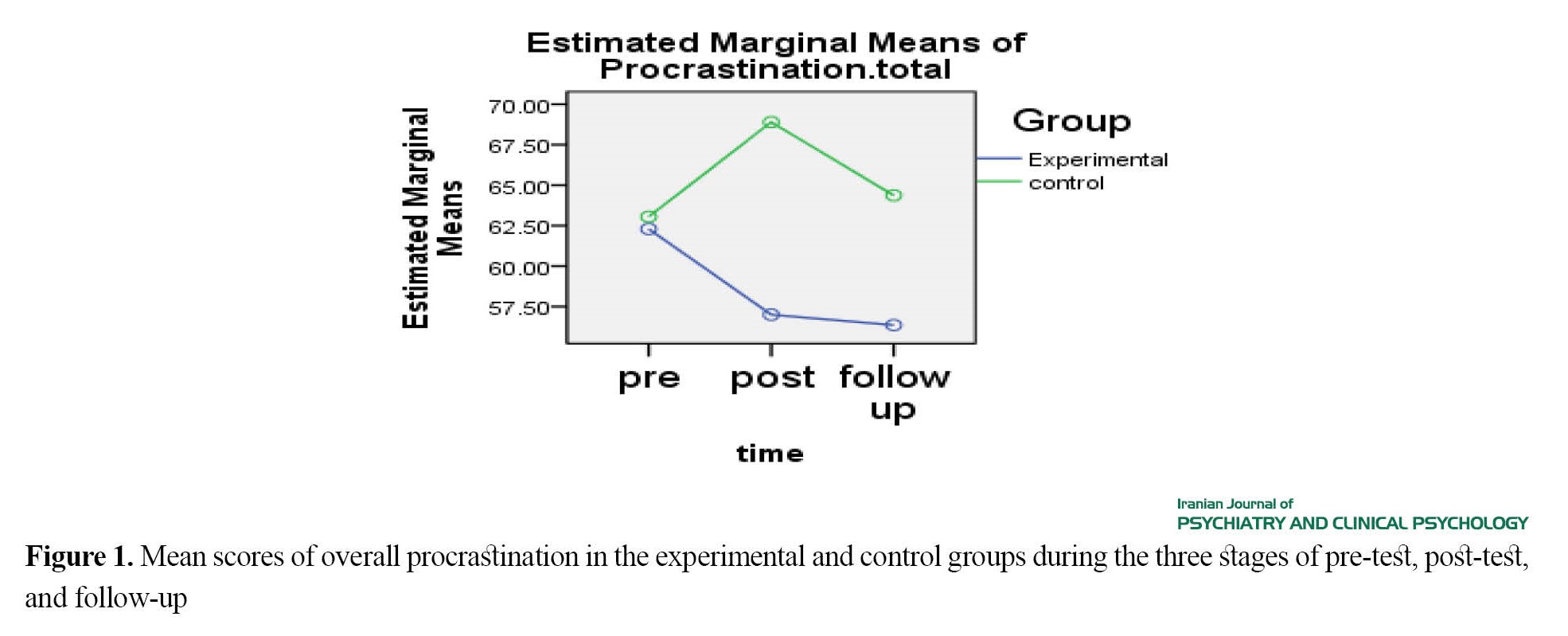

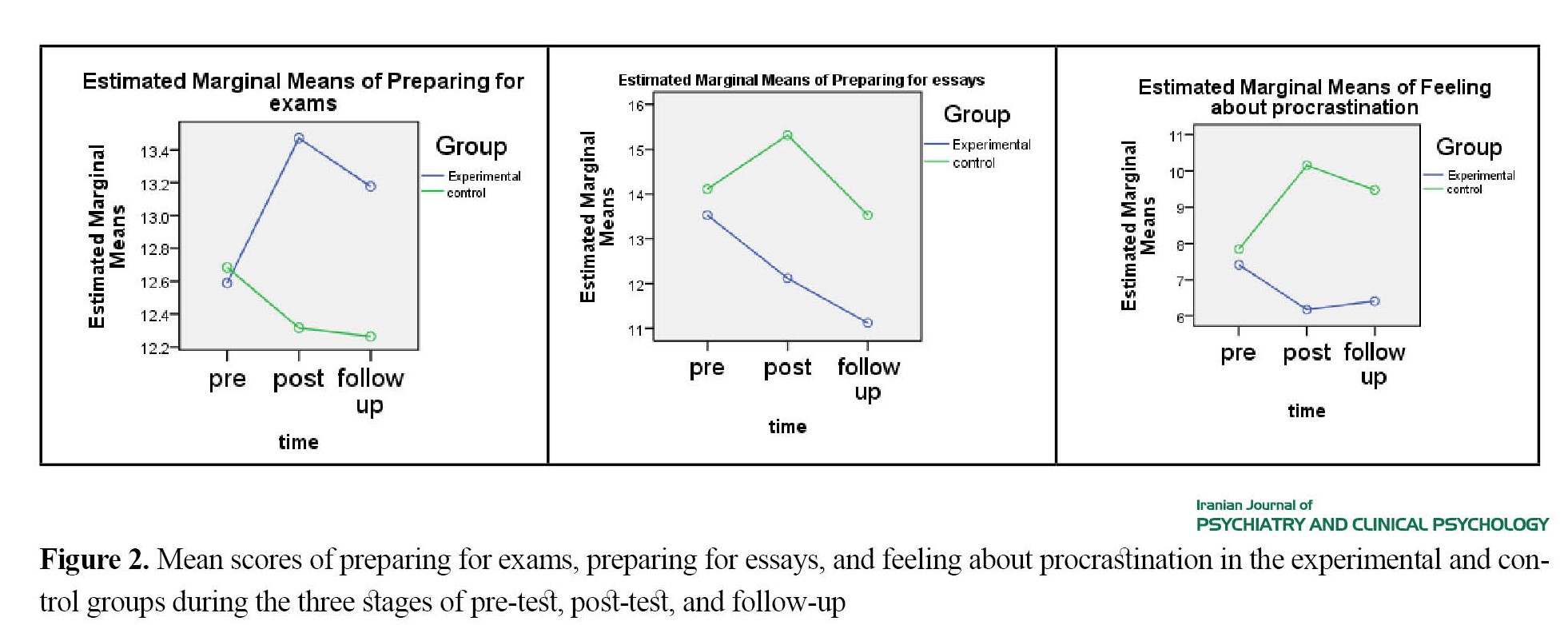

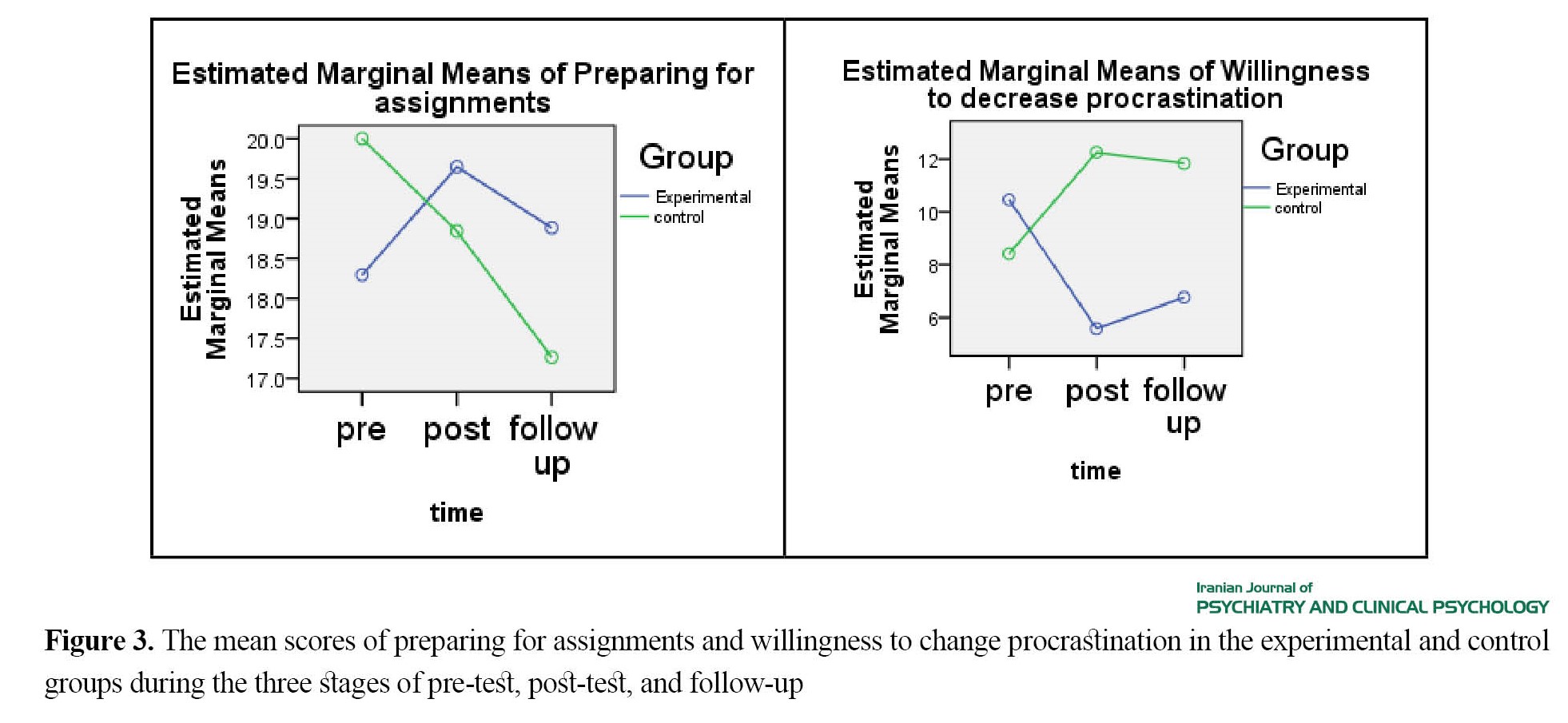

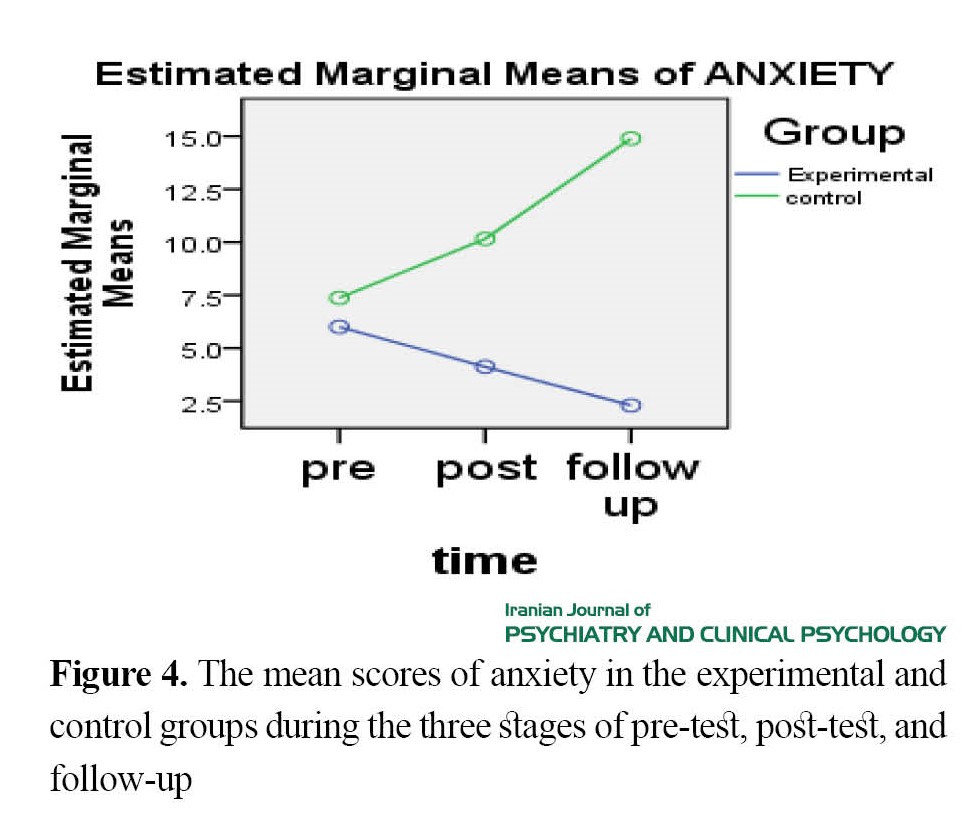

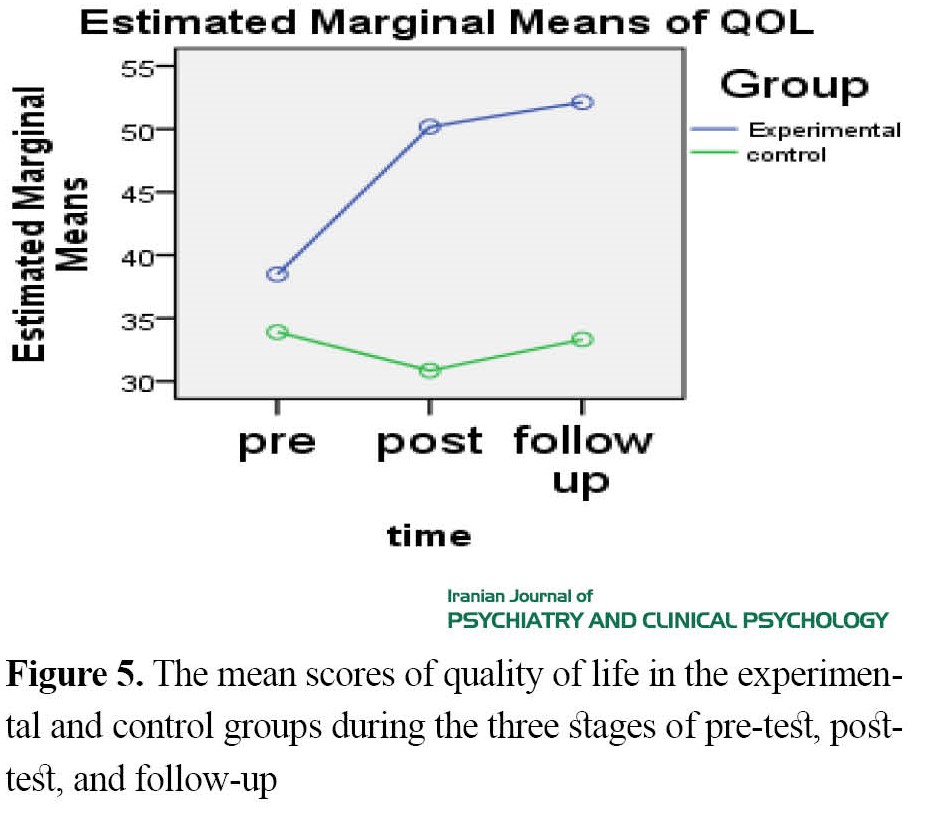

The Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 present the average scores in anxiety and QoL, as well as the total score of procrastination and its subscales in the experimental and control groups during the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages.

Discussion

The present study’s findings support that CFT can significantly reduce procrastination and other symptoms in students. This finding aligns with previous studies showing that compassion-focused therapy can reduce academic procrastination [32-34]. The result is also consistent with findings that show the mediating role of self-compassion between stress and trait procrastination [35]. In justifying this finding, it can be assumed that CFT can reduce procrastination by balancing the three emotion regulation systems and, as a result, improving emotion regulation. As researchers have suggested, ineffective emotion regulation is one of the most important reasons for procrastination [10, 36, 37]. The procrastinator, when experiencing unpleasant feelings such as anxiety [38] or fear of failure [39], prefers not to think about the task (the task that caused these unpleasant emotional states) and postpones it to get rid of these unpleasant mental and physical states. To be more specific, CFT, by increasing the activity of the soothing system and decreasing that of the threat system, helps the person to have more effective emotion regulation and thus reduces their procrastination rate. In other words, when there is harmony between the three emotion regulation systems, individuals are not overwhelmed by intense emotions while facing difficult or unpleasant tasks but prioritize their needs. Optimal activity of the drive system is essential for a person to achieve their goals. The optimal functioning of the drive system keeps the person motivated to try to do their best on tasks.

Also, the study findings support the effectiveness of group compassion-focused therapy in improving the QoL students who procrastinate. This finding is entirely consistent with previous research [42]. To explain this result, it can be said that procrastination reduces the QoL due to its unpleasant and harmful consequences. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that CFT can increase students’ QoL by reducing the levels of their procrastination. In addition, compassion-focused therapy reduces the activity level of the threat-based emotion-regulation system and the soothing emotion-regulation system, increases the number of pleasant emotions, and reduces the number of unpleasant emotions in people. In this way, it can effectively improve people’s QoL.

The present study also showed the effectiveness of CFT in reducing anxiety levels among students with procrastination. To explain this finding, it can be argued that anxiety is an emotion that acts in the service of the threat-based system: Anxiety makes the person more vigilant to the threats of the environment [43]. Then, high anxiety means a high activity of the threat-based system and possibly a low activity of the soothing emotion regulation system. Thus, compassion-focused therapy, by reducing the activity level of the threat-based system and increasing the activity level of the soothing system, can reduce anxiety.

One of the limitations of this study includes the lack of long-term follow-up of treatment results, so it is unclear to what extent the therapeutic effects will be maintained in the long term. Second, sample selection was voluntary and purposive and was limited to a specific geographical area with a limited number of subjects. So, the researchers should be cautious when generalizing the study results. Third, using self-report tools to measure research variables is another study limitation that can highlight the measurement limitations. It is suggested that to determine the effects of compassion-focused therapy over time, in subsequent studies, the sample should be followed up in one or more stages after the post-test, and similar studies be performed on samples with a greater number of participants and a greater variety of indigenous and demographic characteristics. Future therapies can compare the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy with other treatments for procrastinators.

Conclusion

The present study investigated the effectiveness of group-based compassion-focused therapy on academic procrastination, QoL, and anxiety in university students. The findings showed that G-CFT can significantly reduce students’ academic procrastination, QoL, and anxiety and increase their QoL.

Although the findings of this study showed that group CFT, like individual CFT, can significantly improve academic procrastination and other variables in the students, generalization of results should be made cautiously due to significant limitations such as lack of long-term follow-up and the small number of participants. CFT still needs more research with a larger sample size and longer follow-up to become an evidence-based treatment for procrastination.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC 1396.31889) and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT no: IRCT20141108019855N6).

Funding

This study was conducted with the support of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, research and writing the original draft: Ahmad Ashouri, Samira Masoumian and Esfandiar Mehravin; Supervision: Ahmad Ashouri and Samira Masoumian; Formal analysis: Samira Masoumian, Zahra Ghadyan, Neda Moradi, and Samira Shams Sobhani; Review and editing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Iran University of Medical Sciences for their financial assistance and all the patients who participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

Procrastination is “the voluntary delay of an intended, necessary, and or personally important activity, despite expecting potential negative consequences that outweigh the positive consequences of the delay” [1]. One specific form of procrastination is academic procrastination. This type is restricted to the tasks and activities related to learning and studying [2]. Academic procrastination is a common problem among students. According to some reports, about 70% of students identify themselves as procrastinators in areas like writing papers and reading for exams. Instead, they tend to engage in more pleasant activities [3]. Procrastination can have functions such as failure avoidance and protecting oneself against being hurt. That is why procrastination is so common among students [4]. Procrastination has many adverse consequences. It negatively affects subjective wellbeing [5], academic achievement and self-efficacy [6], and financial and occupational issues [7]. Procrastination is also associated with low self-compassion [8], low mindfulness [9], emotion regulation difficulties [10], depression [11], and anxiety [12].

Research has also shown that self-compassion can act as a mediator between stress and depression [8]. It has been suggested that for some students, procrastination can act as an emotion regulation strategy that provides instantaneous emotional relief [13, 14]. According to Gilbert [15], an imbalance between the neurocognitive processes underlying emotion regulation, especially the inadequate activity of the system responsible for producing emotional calmness (the soothing system), elucidates why people usually do not feel emotionally relaxed, even if they are helped in traditional treatments to change their thoughts and behaviors.

Therefore, Gilbert designed a treatment program (called compassion-focused therapy [CFT]) to activate the soothing system. From an evolutionary perspective, Gilbert explains how humans have developed three emotion regulation systems: Threat, motivational, and soothing. The threat system, related to harm avoidance behaviors, works by creating emotions such as anger and fear. The motivational or drive system, related to reward approach behaviors, creates emotions such as ambition and sexual desire. Finally, the soothing system is related to social mentality and the attachment system and works by creating emotions, such as sympathy and compassion. According to Gilbert, the threat system is highly developed in people who often experience negative emotions, and the soothing system is underdeveloped [15-18]. It can be assumed that the threat system in procrastinators is hyperactive, and their soothing system is underactive. Thus, they prefer to postpone their tasks to eliminate unpleasant feelings when doing tasks. Accordingly, one of the mechanisms through which CFT can help procrastinators is balancing their three emotion regulation systems. Creating a balance between the three emotion regulation systems, people with more effective emotion regulation do not have to postpone their tasks to get rid of unpleasant feelings when faced with tasks that require hard work.

According to what was discussed and previous studies, we conducted this research with the assumption that group CFT can significantly improve academic procrastination, anxiety, and quality of life (QoL) in university students.

Methods

This research is an experimental study of clinical trial type. The statistical population of this study included all students of Iran University of Medical Sciences. Using convenience sampling, 40 students were selected as a statistical sample and then randomly divided into control and experimental groups. The inclusion criteria were being 18 to 45 years old, obtaining a minimum score on the procrastination questionnaire, not suffering from clinical disorders such as psychotic disorders or substance use disorder based on the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 clinical disorders (SCID-5-CV), lacking a severe personality disorder based on Milon such as schizotypal, paranoid, and schizoid based on the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 personality disorders (SCID-5-PD), and being willing to cooperate in the therapy sessions. The experimental group received eight 120-minute sessions of group compassion-focused therapy once a week, while the control group received no intervention. The study tools included a demographic questionnaire; academic procrastination questionnaire; depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21); and personal wellbeing index-adult (PWI-A). The eight-session program used for the experimental group was designed according to the Gilbert guide [31].

Research tools

Demographic questionnaire

A researcher-made questionnaire was used to obtain demographic information of the students, which includes items such as age, sex, marital status, employment status, educational status, previous history and duration of psychiatric and psychological disorders (clinical and personality disorders), and received treatments (pharmacological and non-pharmacological).

Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders-clinical version (SCID-5-CV)

This tool is a semi-structured clinical and diagnostic interview developed by First et al. in 2015 to assess clinical disorders [22], including anxiety and mood disorders, psychosis, and substance abuse. Each disorder’s level of damage and severity can be evaluated using this tool. The validity and reliability of this tool have been examined and confirmed [23].

Structured clinical interview for personality disorders DSM-5 (SCID-5-PD)

In 2015, First et al. designed a new version of the structured diagnostic interview based on DSM-5 to evaluate 10 personality disorders [24]. The results of the study confirm its validity and reliability. In this study, in diagnoses related to obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizotypal, schizoid, dramatic, narcissistic, borderline, and antisocial personality disorder, the kappa value is higher than 0.4. In diagnoses related to avoidant, dependent, and other personality disorders, the kappa value was lower than 0.4 [25].

The academic procrastination scale

This scale was developed in 1984 by Solomon and Rothblum to assess student procrastination and has 27 items and 5 subscales. Responders can show their agreement rate with each item by choosing one of the options: Rarely, sometimes, or always [26].

Depression, anxiety and stress scale-21 (DASS-21)

The short form has 21 items with 3 subscales (depression, anxiety, and stress). The participants should rate the intensity (frequency) of the symptoms they have experienced over the past week using a 4-point scale (between 0 and 3). This scale has been confirmed by factor analysis, and the results indicate the convergent and divergent validity of this scale. The scale validity was also studied using the test re-test method, confirming its validity in general Iranian society [29].

Personal wellbeing index-adult (PWI-A)

PWI-A contains 7 items of satisfaction, each related to an area of QoL, including material level of life, health, personal relationships, safety, achievements in life, position, and social security in the future. Each scale question is scored between 0 and 10. In Iran, the research findings showed that the scale has good reliability based on the whole scale alpha coefficient (0.89) and correlation coefficient of its re-test (0.79). Also, the obtained correlation coefficients indicate the convergent validity of the scale with similar instruments [30].

Results

Using the chi-square test to compare the experimental and control groups in variables such as gender, occupation, marital status, educational status, previous history of physical and psychological illness, and history of referring and receiving pharmaceutical and non-pharmacological treatments showed no statistically significant differences. Therefore, the two studied groups are comparable in terms of these variables.

Now, the experimental and control groups’ changes in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages are investigated (Table 1).

According to the principle of normality and sphericity of the studied variables, the GLM repeated measures analysis of variance (GLMRM) was used.

The Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 present the average scores in anxiety and QoL, as well as the total score of procrastination and its subscales in the experimental and control groups during the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages.

Discussion

The present study’s findings support that CFT can significantly reduce procrastination and other symptoms in students. This finding aligns with previous studies showing that compassion-focused therapy can reduce academic procrastination [32-34]. The result is also consistent with findings that show the mediating role of self-compassion between stress and trait procrastination [35]. In justifying this finding, it can be assumed that CFT can reduce procrastination by balancing the three emotion regulation systems and, as a result, improving emotion regulation. As researchers have suggested, ineffective emotion regulation is one of the most important reasons for procrastination [10, 36, 37]. The procrastinator, when experiencing unpleasant feelings such as anxiety [38] or fear of failure [39], prefers not to think about the task (the task that caused these unpleasant emotional states) and postpones it to get rid of these unpleasant mental and physical states. To be more specific, CFT, by increasing the activity of the soothing system and decreasing that of the threat system, helps the person to have more effective emotion regulation and thus reduces their procrastination rate. In other words, when there is harmony between the three emotion regulation systems, individuals are not overwhelmed by intense emotions while facing difficult or unpleasant tasks but prioritize their needs. Optimal activity of the drive system is essential for a person to achieve their goals. The optimal functioning of the drive system keeps the person motivated to try to do their best on tasks.

Also, the study findings support the effectiveness of group compassion-focused therapy in improving the QoL students who procrastinate. This finding is entirely consistent with previous research [42]. To explain this result, it can be said that procrastination reduces the QoL due to its unpleasant and harmful consequences. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that CFT can increase students’ QoL by reducing the levels of their procrastination. In addition, compassion-focused therapy reduces the activity level of the threat-based emotion-regulation system and the soothing emotion-regulation system, increases the number of pleasant emotions, and reduces the number of unpleasant emotions in people. In this way, it can effectively improve people’s QoL.

The present study also showed the effectiveness of CFT in reducing anxiety levels among students with procrastination. To explain this finding, it can be argued that anxiety is an emotion that acts in the service of the threat-based system: Anxiety makes the person more vigilant to the threats of the environment [43]. Then, high anxiety means a high activity of the threat-based system and possibly a low activity of the soothing emotion regulation system. Thus, compassion-focused therapy, by reducing the activity level of the threat-based system and increasing the activity level of the soothing system, can reduce anxiety.

One of the limitations of this study includes the lack of long-term follow-up of treatment results, so it is unclear to what extent the therapeutic effects will be maintained in the long term. Second, sample selection was voluntary and purposive and was limited to a specific geographical area with a limited number of subjects. So, the researchers should be cautious when generalizing the study results. Third, using self-report tools to measure research variables is another study limitation that can highlight the measurement limitations. It is suggested that to determine the effects of compassion-focused therapy over time, in subsequent studies, the sample should be followed up in one or more stages after the post-test, and similar studies be performed on samples with a greater number of participants and a greater variety of indigenous and demographic characteristics. Future therapies can compare the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy with other treatments for procrastinators.

Conclusion

The present study investigated the effectiveness of group-based compassion-focused therapy on academic procrastination, QoL, and anxiety in university students. The findings showed that G-CFT can significantly reduce students’ academic procrastination, QoL, and anxiety and increase their QoL.

Although the findings of this study showed that group CFT, like individual CFT, can significantly improve academic procrastination and other variables in the students, generalization of results should be made cautiously due to significant limitations such as lack of long-term follow-up and the small number of participants. CFT still needs more research with a larger sample size and longer follow-up to become an evidence-based treatment for procrastination.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC 1396.31889) and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT no: IRCT20141108019855N6).

Funding

This study was conducted with the support of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, research and writing the original draft: Ahmad Ashouri, Samira Masoumian and Esfandiar Mehravin; Supervision: Ahmad Ashouri and Samira Masoumian; Formal analysis: Samira Masoumian, Zahra Ghadyan, Neda Moradi, and Samira Shams Sobhani; Review and editing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Iran University of Medical Sciences for their financial assistance and all the patients who participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

- Klingsieck KB. Procrastination. European Psychologist. 2013; 18(1):24-34. [DOI:10.1027/1016-9040/a000138]

- Steel P, Klingsieck KB. Academic procrastination: Psychological antecedents revisited. Australian Psychologist. 2016; 51(1):36-46. [DOI:10.1111/ap.12173]

- Grunschel C, Patrzek J, Fries S. Exploring reasons and consequences of academic procrastination: An interview study. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2013; 28:841-61. [DOI:10.1007/s10212-012-0143-4]

- Duru E, Balkis M. The roles of academic procrastination tendency on the relationships among self doubt, self esteem and academic achievement. Egitim ve Bilim. 2014; 39(173):274-87. [Link]

- Soomro BA, Shah N. Is procrastination a “friend or foe”? Building the relationship between fear of the failure and entrepreneurs’ well-being. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies. 2022; 14(6):1054-71. [DOI:10.1108/JEEE-12-2019-0191]

- Najma RUA, Sultan S. Role of procrastination in mental wellbeing and academic achievement through academic self-efficacy. Psychology and Education Journal. 2021; 58(4):4088-95. [Link]

- Nguyen B, Steel P, Ferrari JR. Procrastination’s impact in the workplace and the workplace’s impact on procrastination. International Journal of Selection and Assessment. 2013; 21(4):388-99. [DOI:10.1111/ijsa.12048]

- Sirois FM. Procrastination and stress: Exploring the role of self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2014; 13(2):128-45. [DOI:10.1080/15298868.2013.763404]

- Sirois FM, Tosti N. Lost in the moment? An investigation of procrastination, mindfulness, and well-being. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2012; 30(4):237-48. [DOI:10.1007/s10942-012-0151-y]

- Eckert M, Ebert DD, Lehr D, Sieland B, Berking M. Overcome procrastination: Enhancing emotion regulation skills reduce procrastination. Learning and Individual Differences. 2016; 52:10-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.lindif.2016.10.001]

- Uzun Ozer B, O’Callaghan J, Bokszczanin A, Ederer E, Essau C. Dynamic interplay of depression, perfectionism and self-regulation on procrastination. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2014; 42(3):309-19. [DOI:10.1080/03069885.2014.896454]

- Scher SJ, Osterman NM. Procrastination, conscientiousness, anxiety, and goals: Exploring the measurement and correlates of procrastination among school-aged children. Psychology in The Schools. 2002; 39(4):385-98. [DOI:10.1002/pits.10045]

- Hen M, Goroshit M. The effects of decisional and academic procrastination on students feelings toward academic procrastination. Current Psychology. 2018; 39(2):556-63. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-017-9777-3]

- Pychyl TA, Sirois FM. Procrastination, emotion regulation, and well-being. Procrastination, Health, and Well-being. 2016 ; 163-88. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-802862-9.00008-6]

- Gilbert P. Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2009; 15(3):199-208. [DOI:10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264]

- Gilbert P. Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. Milton Park: Routledge; 2005. [Link]

- Gilbert P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014; 53(1):6-41. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12043] [PMID]

- MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012; 32(6):545-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003] [PMID]

- van Eerde W, Klingsieck KB. Overcoming procrastination? A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Educational Research Review. 2018; 25:73-85. [DOI:10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.002]

- Sirois F, Pychyl T. Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2013; 7(2):115-27. [DOI:10.1111/spc3.12011]

- Ferrari JR, Johnson JL, McCown WG. Procrastination and task avoidance: Theory, research, and treatment. Berlin: Springer; 1995. [Link]

- First MB, Williams JB, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. SCID-5-CV: Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders: Clinician version. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association Pub; 2016. [Link]

- Shabani A, Masoumian S, Zamirinejad S, Hejri M, Pirmorad T, Yaghmaeezadeh H. Psychometric properties of structured clinical interview for DSM-5 Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV). Brain and Behavior. 2021; 11(5):e01894. [DOI:10.1002/brb3.1894] [PMID]

- First MB, Williams JB, Benjamin LS, Spitzer RL. SCID-5-PD: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders. Washington, D.C:American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2015. [Link]

- Gharraee B, Shabani A, Masoumian S, Zamirinejad S, Yaghmaeezadeh H, Khanjani S, et al. Psychometric properties of Persian version of structured clinical interview for dsm-5 for personality disorders. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry. 2022; 32(4):95-9. [DOI:10.12809/eaap2208] [PMID]

- Solomon LJ, Rothblum E. Procrastination assessment scale-students. Dictionary of Behavioral Assessment Techniques. 1988; 358-60. [Link]

- Ali Madad Z. [Examining the role of self-determination in the relationship between aspects of parenting and academic procrastination of Shiraz students (Persian)] [MA thesis]. Shiraz: Shiraz University; 2008

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995; 33(3):335-43. [DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U] [PMID]

- Samani S, Joukar B. [A study on the reliability and validity of the short form of the depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21) (Persian)]. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Shiraz University. 2007; 26(3):65-76. [Link]

- Nainian M, Nik Azin A, Shairi M, Rajabi M, Soltaninejad Z. [Reliability and Validity of Adultsâ Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI-A) (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology and Personality. 2020; 15(1):189-99. [DOI:10.22070/CPAP.2017.15.1.189]

- Cheng FK. Compassion focused therapy: The CBT distinctive features series. 2014. [DOI:10.1080/13674676.2012.755617]

- Ghodrati A, Aradmehr M, Sharifi Z. The effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on academic procrastination and cognitive-emotional regulation of first-grade high school students in Mashhad. Research in Health and Medical Sciences. 2022; 1(2):1-8. [Link]

- Tarkhan M. [The effectiveness of compassion focused therapy (CFT) on academic resili-ency and hopefulness in the academic procrastination of male students of the second degree of high school (Persian)]. Research in School and Virtual Learning. 2021; 8(4):9-18. [DOI:0.30473/etl.2021.57643.3435]

- Sirois FM. Procrastination and stress: Exploring the role of self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2014; 13(2):128-45. [DOI:10.1080/15298868.2013.763404]

- Wartberg L, Thomasius R, Paschke K. The relevance of emotion regulation, procrastination, and perceived stress for problematic social media use in a representative sample of children and adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior. 2021; 121:106788. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106788]

- Mohammadi Bytamar J, Saed O, Khakpoor S. Emotion regulation difficulties and academic procrastination. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:524588. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.524588] [PMID]

- Zhang R, Chen Z, Xu T, Zhang L, Feng T. The overlapping region in right hippocampus accounting for the link between trait anxiety and procrastination. Neuropsychologia. 2020; 146:107571. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107571] [PMID]

- Schouwenburg HC. Procrastinators and fear of failure: An exploration of reasons for procrastination. European Journal of personality. 1992; 6(3):225-36. [DOI:10.1002/per.2410060305]

- Mansouri K, Ashouri A, Gharaei B, Farahani H. [The mediating role of fear of failure, self-compassion and in-tolerance of uncertainty in the relationship between academic procrastination and perfectionism (Persian)]. Iranian Journal o f Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2022; 28(1):34-47. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.28.1.3706.1]

- Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007; 41(1):139-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004]

- Neff K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003; 2(2):85-101. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309032]

- Bishop SJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: An integrative account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007; 11(7):307-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.008] [PMID]

- Ashby JS, Bruner LP. Multidimensional perfectionism and obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Journal of College Counseling. 2005; 8(1):31-40. [DOI:10.1002/j.2161-1882.2005.tb00070.x]

- Al-Shorman E, Jaradat AK. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among adaptive perfectionists’ maladaptive perfectionists and non-perfectionists. Jordan Journal of Educational Sciences. 2022; 18(4):629-45. [Link]

- Chen S. Give yourself a break: The power of self-compassion. Harvard Business Review. 2018; 96(5):117-23. [Link]

- Sirois FM, Kitner R, Hirsch JK. Self-compassion, affect, and health-promoting behaviors. Health Psychology. 2015; 34(6):661-9. [DOI:10.1037/hea0000158] [PMID]

- Saplavska J, Jerkunkova A. Academic procrastination and anxiety among students. Paper presented at: 17th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development. 23 May 2018; Jelgava, Latvia. [Link]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2023/07/23 | Accepted: 2023/08/18 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2023/07/23 | Accepted: 2023/08/18 | Published: 2024/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |