Sun, Jul 14, 2024

| فارسی

Volume 29, Issue 4 (Winter 2024)

IJPCP 2024, 29(4): 384-401 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mirbagheri A M, Zanjani Z, Omidi A, Azadchehreh M J. Effect of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Emotional Regulation, Psychological Flexibility, and Stress in Children of Veterans With PTSD: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. IJPCP 2024; 29 (4) :384-401

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3961-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3961-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehtan, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran. ,z_zanjani2005@yahoo.com

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

4- Infectious Diseases Research Center of Shahid Beheshti Hospital, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran. ,

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

4- Infectious Diseases Research Center of Shahid Beheshti Hospital, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

Keywords: Post-traumatic Stress disorders, Emotional regulation, Psychological flexibility, Acceptance and commitment Therapy, Child, Veterans

Full-Text [PDF 7001 kb]

(330 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (846 Views)

Full-Text: (63 Views)

Introduction

The experience of war and various traumas can hurt individuals physically and psychologically. Studies have shown that war traumas have a negative impact on the psychological health of veterans [1]. One of the primary consequences of war in veterans is the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which can affect their family members, including wife or children [9]. The fathers’ PTSD can affect the emotional regulation strategies of children [14]. Emotional dysregulation is one of the most common problems in psychological disorders, including PTSD [15], which can lead to interpersonal problems in veterans with PTSD and their children [14]. Moreover, the parents’ PTSD can have a negative impact on the psychological flexibility of children [1, 10, 26]. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), designed for psychological flexibility and avoidance, can be a suitable method for the integrative treatment of PTSD [30]. Studies has revealed that ACT can be helpful in reducing PTSD symptoms [31]. The present study aims to investigate the effect of ACT on emotional regulation, psychological flexibility, and symptoms in children of veterans with PTSD.

Methods

This is a randomized controlled clinical trial with a pre-test/post-test/follow-up design. Seventy participants were selected by simple random sampling method from among the children of veterans with PTSD (n=180) in Yazd, Iran. According to the inclusion criteria, 70 girls and boys aged 15-19 years were selected and randomly assigned into two groups of 35, including ACT and control. Afterwards, the group ACT was presented to the intervention group, while a 7-session life skills education program was presented to the control group. The data were collected at pre-test, post-test, and 12-month follow-up phases using the acceptance and action questionnaire – version 2 (AAQ-2), the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS), and the PTSD Checklist for PCL. Then, all collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 22 using descriptive (Mean±SD) and inferential (ANOVA and ANCOVA) statistics.

Results

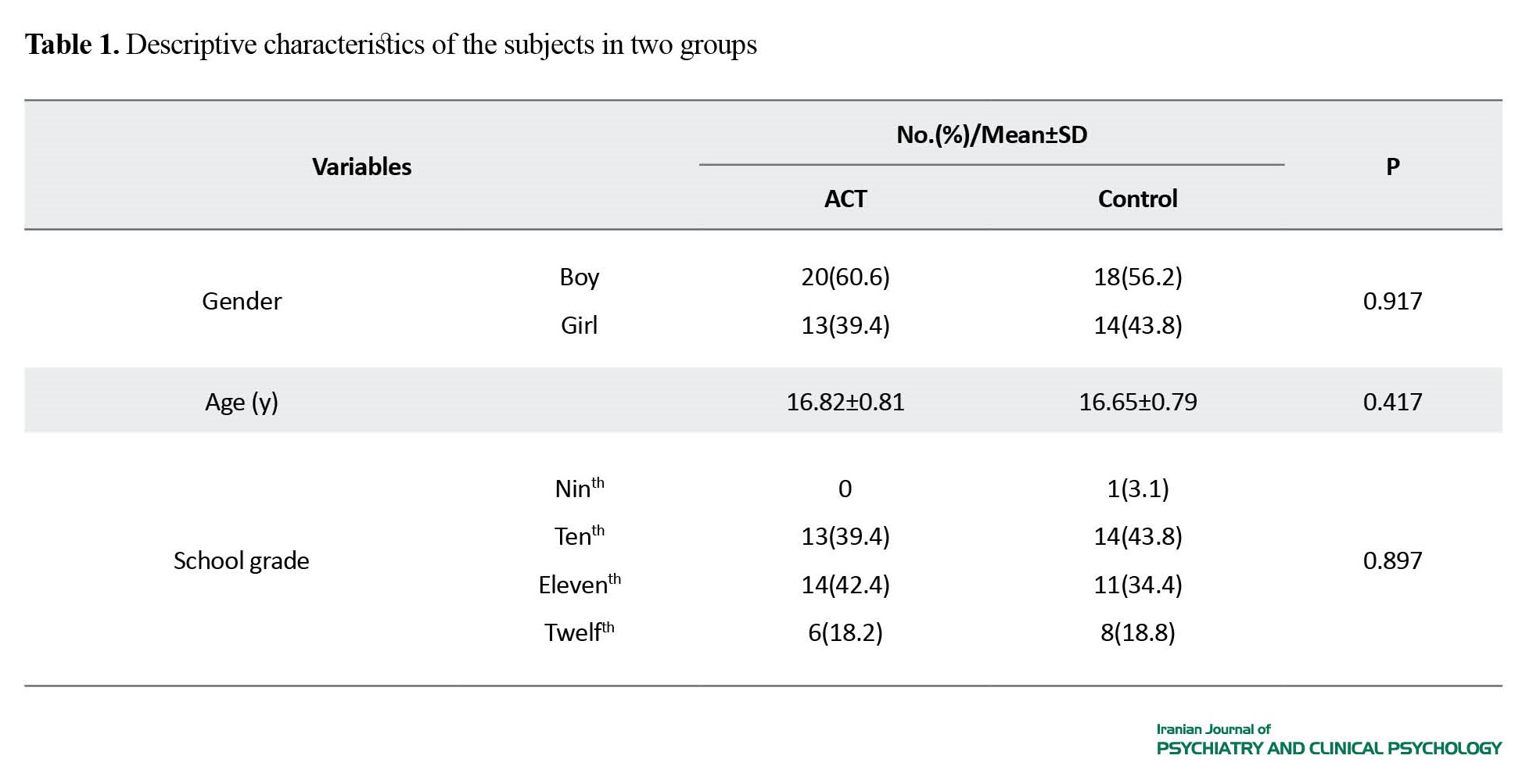

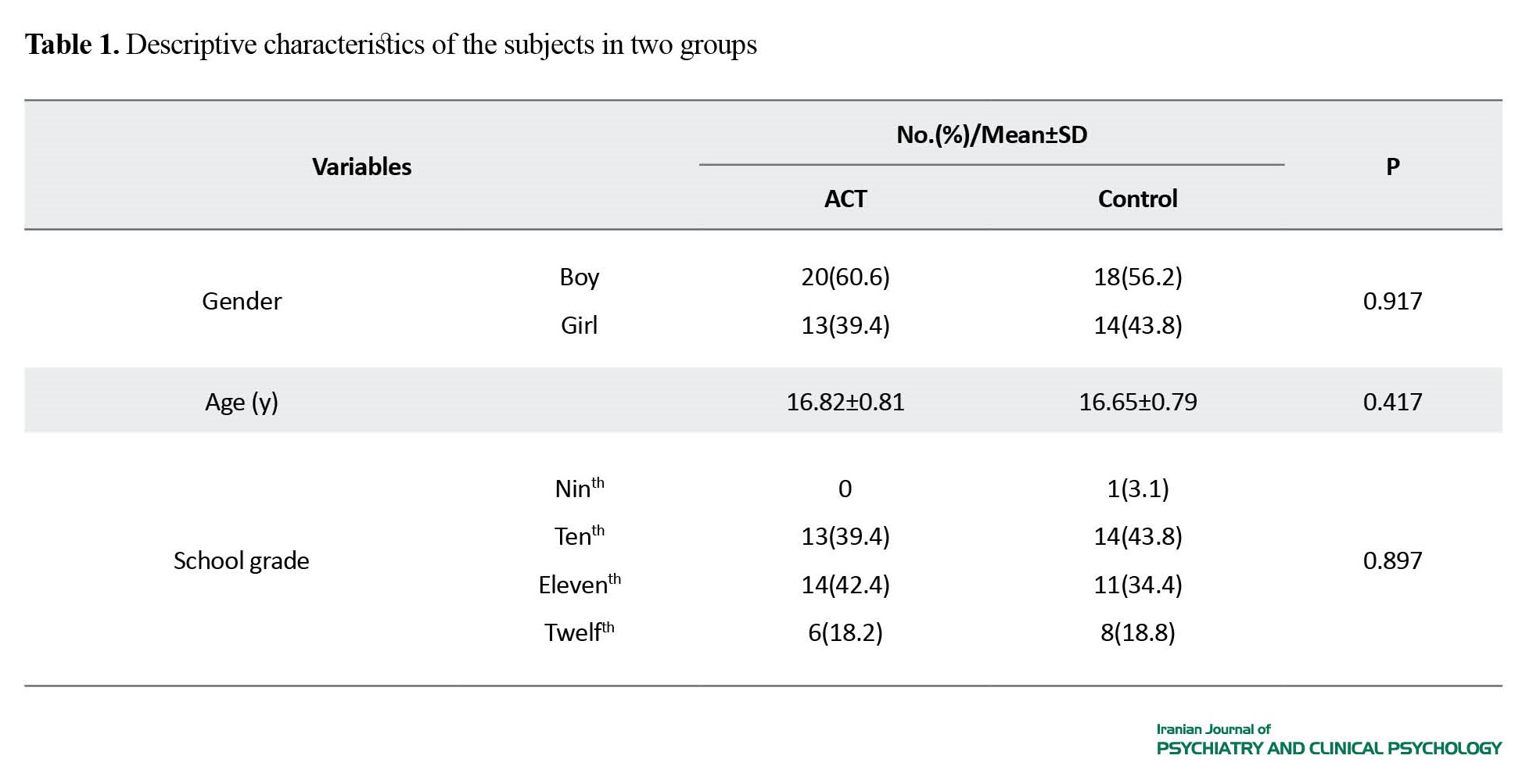

During the treatment process, 5 children (two in the intervention group and three in the control group) left the study, and statistical analysis was carried out on the data of 65 children. In the intervention group, 20(60.6%) were males and 13(39.4%) were females. In the control group, 18(56.2%) were males and 14(43.8%) were females. The mean age of the subjects was 16.82 years in the intervention group and 16.65 years in the control group. In the intervention group, 13(39.4%) were studying in grade 10, 14(42.4%) in grade 11, 6(18.2) in grade 12. In the control group, one (3.1%) was in grade 9, 14(43.8%) in grade 10, 11(34.4%) in grade 11, and 8(18.8%) in grade 12.

It is noteworthy that 40 children received face-to-face intervention and 25 attended online intervention sessions. The number of participants in online and face-to-face sessions was the same in both groups, 5 in the intervention group and 5 in the control group, and there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of the type of presentation, gender, age, and educational level (P>0.05). In other words, both groups were homogenous in terms of demographic factors (Table 1).

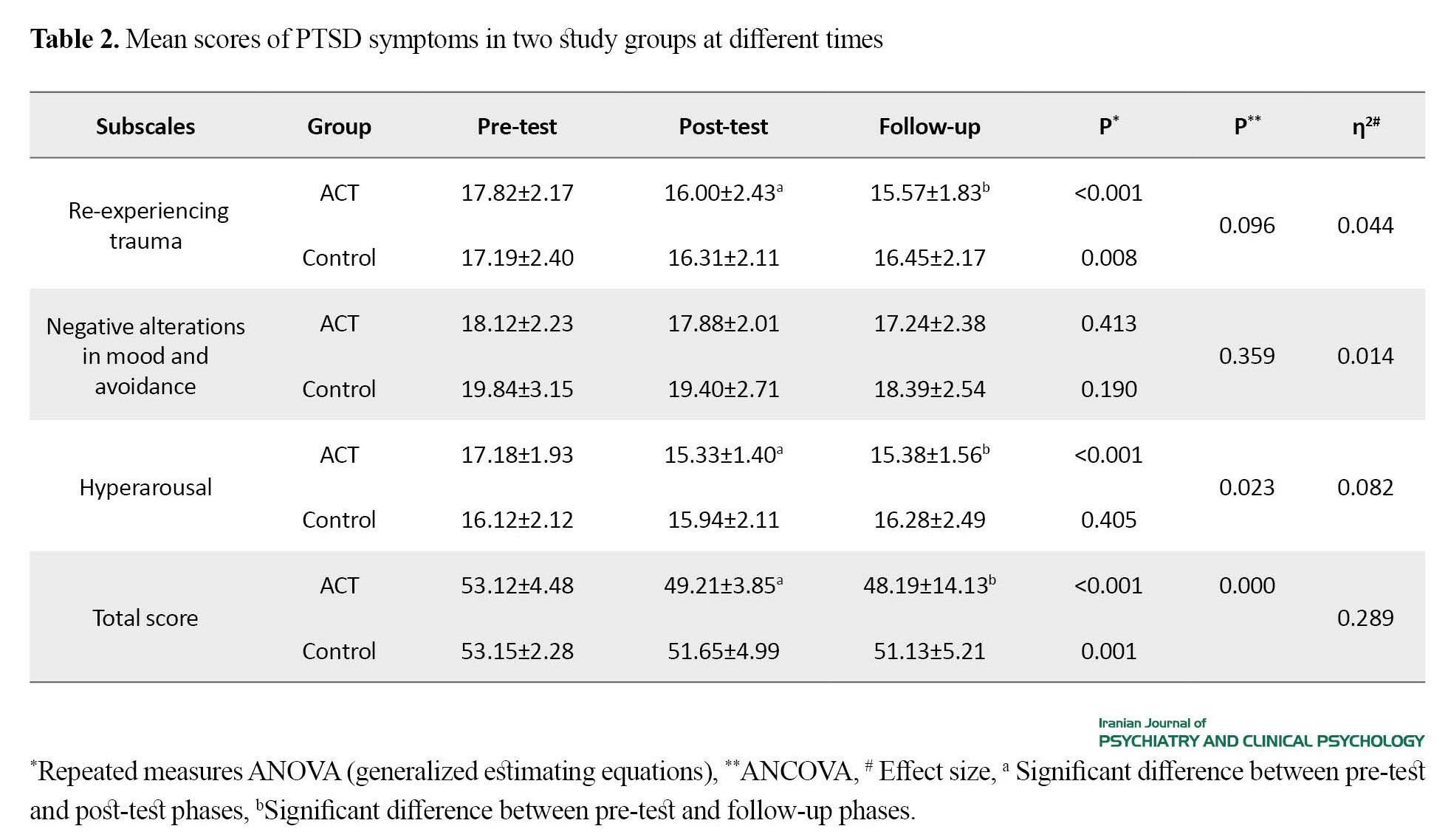

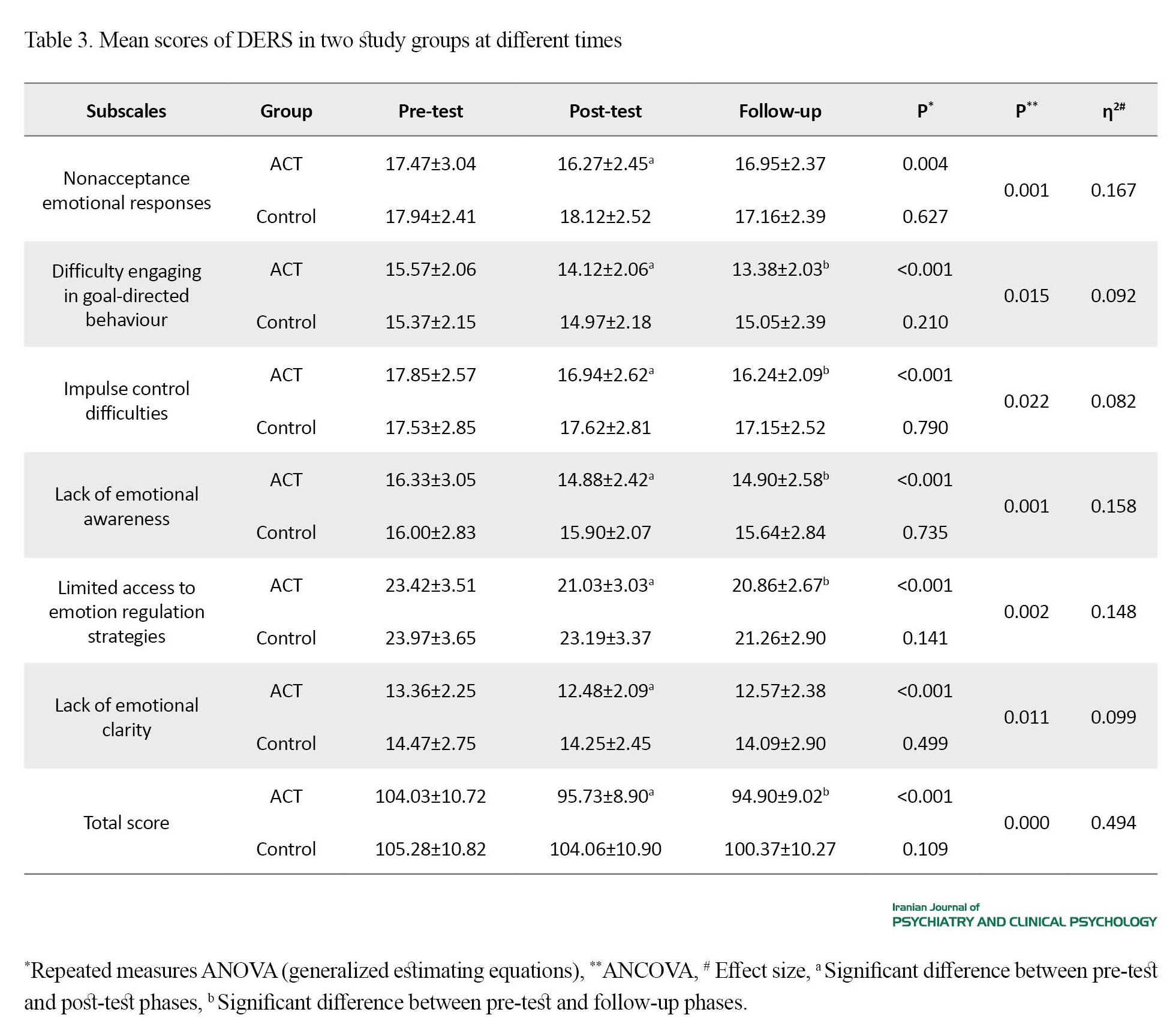

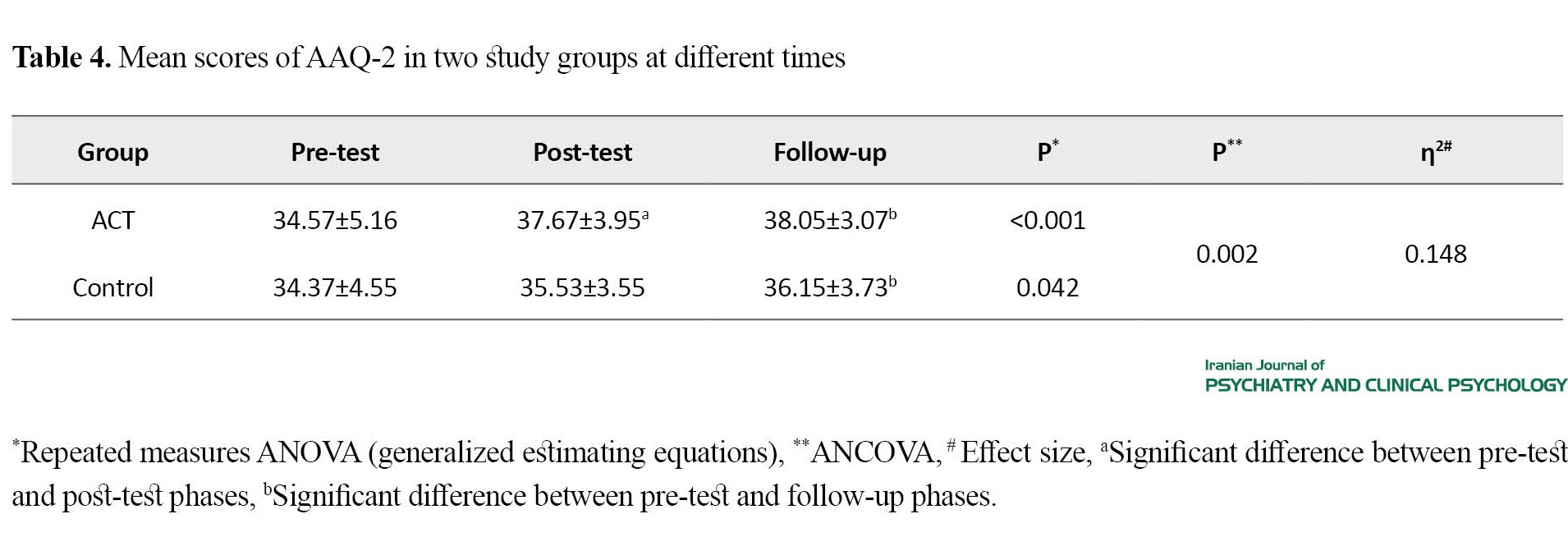

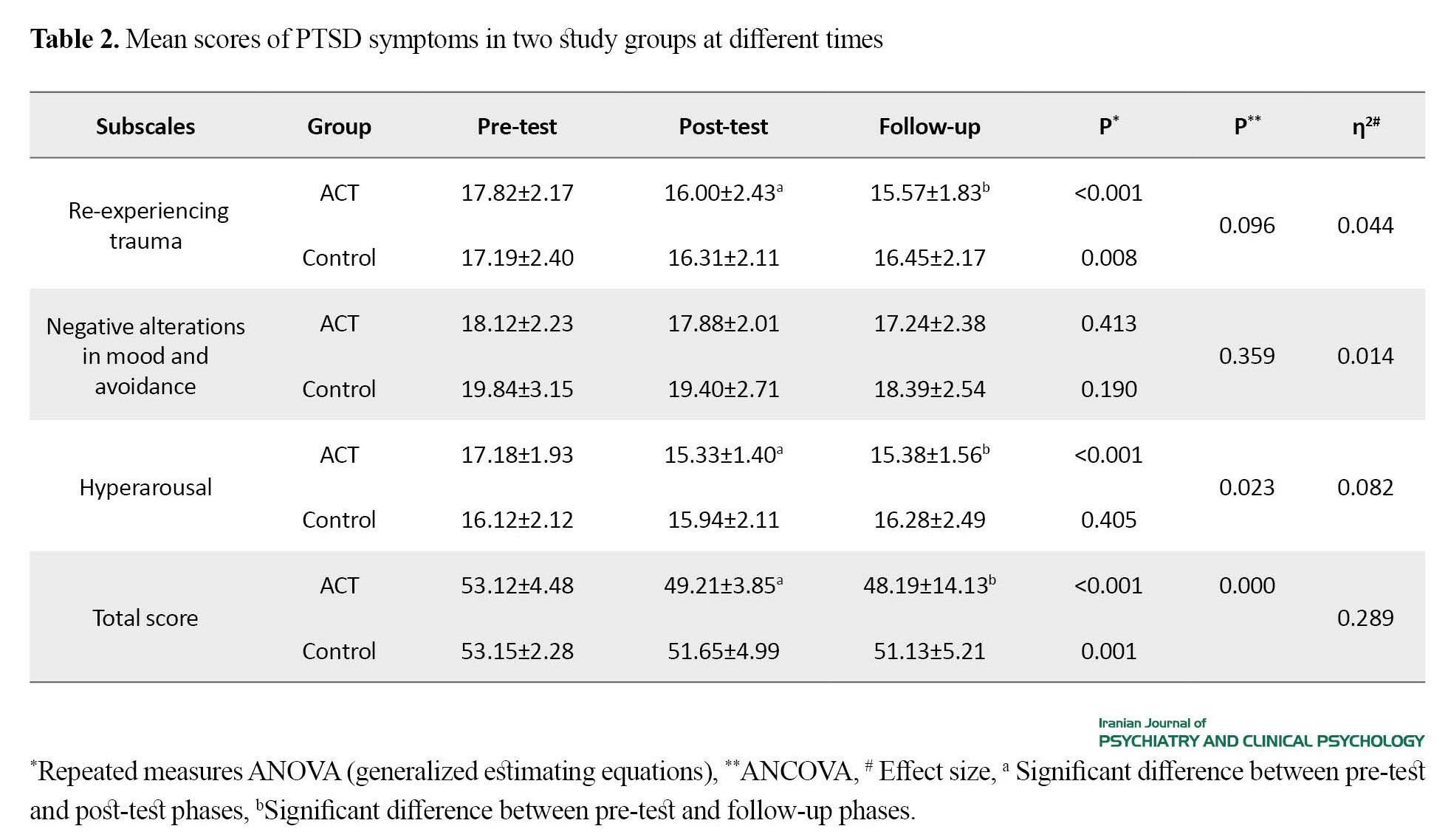

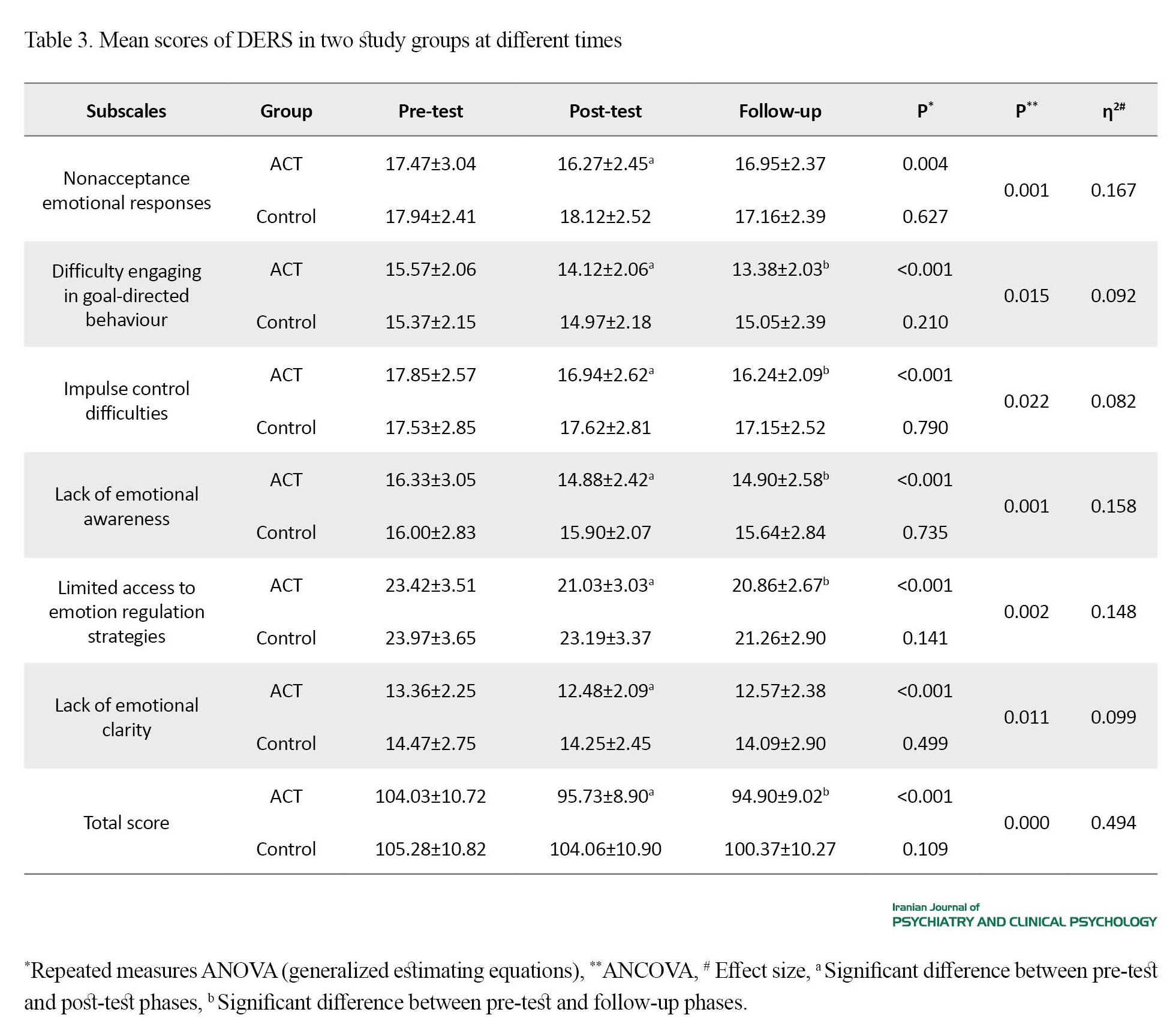

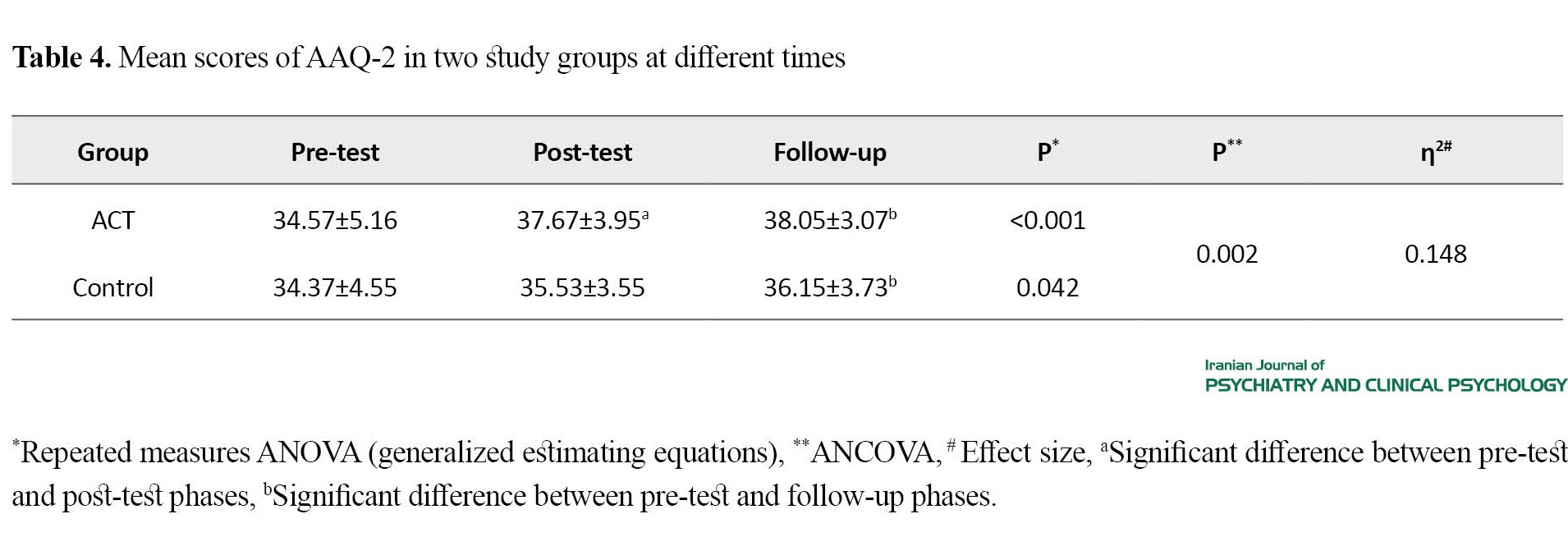

The results presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4 showed that the mean scores of DERS, AAQ-2, and total PTSD symptoms were significantly different between the ACT and control groups (P<0.01).

However, the groups were not significantly different in symptoms of re-experiencing trauma and negative alterations in mood and avoidance (P>0.05), the difference was significant in hyperarousal symptoms. The pre-test and post-test scores in the control group were significantly different in re-experiencing trauma (P<0.01).

Conclusion

The results revealed that ACT improved emotional regulation skills and psychological flexibility of the children of veterans with PTSD. Furthermore, ACT alleviated the hyperarousal symptoms of these children, but it could not reduce negative alterations in mood, avoidance, or re-experiencing symptoms.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.KAUMS.REC.1400.018). The study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: IRCT 20210708051815N1)

Funding

This study was funded by Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Amir Masoud Mirbagheri, Zahra Zanjani and Abdolah Omidi; Methodology, writing, Funding acquisition and resources: Zahra Zanjani and Amir Masoud Mirbagheri.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Deputy for Research and Technology of Kashan University of Medical Sciences, and all participants for their support and cooperation in the present study.

References

The experience of war and various traumas can hurt individuals physically and psychologically. Studies have shown that war traumas have a negative impact on the psychological health of veterans [1]. One of the primary consequences of war in veterans is the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which can affect their family members, including wife or children [9]. The fathers’ PTSD can affect the emotional regulation strategies of children [14]. Emotional dysregulation is one of the most common problems in psychological disorders, including PTSD [15], which can lead to interpersonal problems in veterans with PTSD and their children [14]. Moreover, the parents’ PTSD can have a negative impact on the psychological flexibility of children [1, 10, 26]. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), designed for psychological flexibility and avoidance, can be a suitable method for the integrative treatment of PTSD [30]. Studies has revealed that ACT can be helpful in reducing PTSD symptoms [31]. The present study aims to investigate the effect of ACT on emotional regulation, psychological flexibility, and symptoms in children of veterans with PTSD.

Methods

This is a randomized controlled clinical trial with a pre-test/post-test/follow-up design. Seventy participants were selected by simple random sampling method from among the children of veterans with PTSD (n=180) in Yazd, Iran. According to the inclusion criteria, 70 girls and boys aged 15-19 years were selected and randomly assigned into two groups of 35, including ACT and control. Afterwards, the group ACT was presented to the intervention group, while a 7-session life skills education program was presented to the control group. The data were collected at pre-test, post-test, and 12-month follow-up phases using the acceptance and action questionnaire – version 2 (AAQ-2), the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS), and the PTSD Checklist for PCL. Then, all collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 22 using descriptive (Mean±SD) and inferential (ANOVA and ANCOVA) statistics.

Results

During the treatment process, 5 children (two in the intervention group and three in the control group) left the study, and statistical analysis was carried out on the data of 65 children. In the intervention group, 20(60.6%) were males and 13(39.4%) were females. In the control group, 18(56.2%) were males and 14(43.8%) were females. The mean age of the subjects was 16.82 years in the intervention group and 16.65 years in the control group. In the intervention group, 13(39.4%) were studying in grade 10, 14(42.4%) in grade 11, 6(18.2) in grade 12. In the control group, one (3.1%) was in grade 9, 14(43.8%) in grade 10, 11(34.4%) in grade 11, and 8(18.8%) in grade 12.

It is noteworthy that 40 children received face-to-face intervention and 25 attended online intervention sessions. The number of participants in online and face-to-face sessions was the same in both groups, 5 in the intervention group and 5 in the control group, and there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of the type of presentation, gender, age, and educational level (P>0.05). In other words, both groups were homogenous in terms of demographic factors (Table 1).

The results presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4 showed that the mean scores of DERS, AAQ-2, and total PTSD symptoms were significantly different between the ACT and control groups (P<0.01).

However, the groups were not significantly different in symptoms of re-experiencing trauma and negative alterations in mood and avoidance (P>0.05), the difference was significant in hyperarousal symptoms. The pre-test and post-test scores in the control group were significantly different in re-experiencing trauma (P<0.01).

Conclusion

The results revealed that ACT improved emotional regulation skills and psychological flexibility of the children of veterans with PTSD. Furthermore, ACT alleviated the hyperarousal symptoms of these children, but it could not reduce negative alterations in mood, avoidance, or re-experiencing symptoms.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.KAUMS.REC.1400.018). The study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: IRCT 20210708051815N1)

Funding

This study was funded by Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: Amir Masoud Mirbagheri, Zahra Zanjani and Abdolah Omidi; Methodology, writing, Funding acquisition and resources: Zahra Zanjani and Amir Masoud Mirbagheri.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Deputy for Research and Technology of Kashan University of Medical Sciences, and all participants for their support and cooperation in the present study.

References

- Levin Y, Bachem R, Solomon Z. Traumatization, Marital Adjustment, and Parenting among Veterans and Their Spouses: A Longitudinal Study of Reciprocal Relations. Family Process. 2017; 56(4):926-42. [DOI:10.1111/famp.12257] [PMID]

- Kline AC, Cooper AA, Rytwinksi NK, Feeny NC. Long-term efficacy of psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review. 2018; 59:30-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.009] [PMID]

- Maercker A. Development of the new CPTSD diagnosis for ICD-11. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 2021; 8(1):7. [DOI:10.1186/s40479-021-00148-8] [PMID]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. In: Hyman S, editor. Fear and anxiety. London: Routledge; 2001. [Link]

- Boterhoven de Haan KL, Lee CW, Fassbinder E, Voncken MJ, Meewisse M, Van Es SM, et al. Imagery rescripting and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing for treatment of adults with childhood trauma-related post-traumatic stress disorder: IREM study design. BMC Psychiatry. 2017; 17(1):165. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-017-1330-2] [PMID]

- Jones AL, Rafferty J, Cochran SD, Abelson J, Hanna MR, Mays VM. Prevalence, severity and burden of post-traumatic stress disorder in black men and women across the adult life span. Journal of Aging and Health. 2022; 34(3):401-12. [DOI:10.1177/08982643221086071] [PMID]

- Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017. [Link]

- Alipour MI, Lorestani F. [Post-traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. Tehran: Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation, Veterans Engineering and Medical Research Institute; 2008.

- Ibrahim I, Ismail MF. War-related Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among Refugee Minors. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry. 2018; 27(2):50-65. [Link]

- Foley J, Hassett A, Williams E. ‘Getting on with the job’: A systematised literature review of secondary trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in policing within the United Kingdom (UK). The Police Journal. 2022; 95(1):224-52. [DOI:10.1177/0032258X21990412]

- Xue C, Ge Y, Tang B, Liu Y, Kang P, Wang M, et al. A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related PTSD among military personnel and veterans. PloS One. 2015; 10(3):e0120270. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0120270] [PMID]

- Levin Y, Greene T, Solomon Z. PTSD symptoms and marital adjustment among ex-POWs’ wives. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016; 30(1):72-81. [DOI:10.1037/fam0000170] [PMID]

- Richardson LK, Frueh BC, Acierno R. Prevalence estimates of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: Critical review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010; 44(1):4-19. [DOI:10.3109/00048670903393597] [PMID]

- Gilmore AK, Lopez C, Muzzy W, Brown WJ, Grubaugh A, Oesterle DW, et al. Emotion dysregulation predicts dropout from prolonged exposure treatment among women veterans with military sexual trauma-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Women’s Health Issues. 2020; 30(6):462-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2020.07.004] [PMID]

- Lahav Y, Kanat-Maymon Y, Solomon Z. Secondary traumatization and attachment among wives of former POWs: A longitudinal study. Attachment & Human Development. 2016; 18(2):141-53. [DOI:10.1080/14616734.2015.1121502] [PMID]

- Knefel M, Lueger-Schuster B, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Hyland P. From child maltreatment to ICD-11 complex post-traumatic stress symptoms: The role of emotion regulation and re-victimisation. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2019; 75(3):392-403. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22655] [PMID]

- Leshem S, Keha E, Kalanthroff E. Post-traumatic stress in war veterans and secondary traumatic stress among parents of war veterans five years after the 2014 Israel-Gaza military conflict. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2023; 14(2):2235983. [DOI:10.1080/20008066.2023.2235983] [PMID]

- Davidson AC, Mellor DJ. The adjustment of children of Australian Vietnam veterans: Is there evidence for the transgenerational transmission of the effects of war-related trauma? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001; 35(3):345-51. [DOI:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00897.x] [PMID]

- Friedberg A, Malefakis D. Resilience, trauma, and coping. Psychodynamic Psychiatry. 2022; 50(2):382-409. [DOI:10.1521/pdps.2022.50.2.382] [PMID]

- Denov M. Encountering children and child soldiers during military deployments: The impact and implications for moral injury. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2022; 13(2):2104007. [DOI:10.1080/20008066.2022.2104007] [PMID]

- Mohamadi L, Mohamadkhani P, Dolatshahi B, Golzari M. [Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and their comorbidity with other disorders in eleven to sixteen years old adolescents in the city of Bam (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2010; 16(3):187-94. [Link]

- Durham TA, Byllesby BM, Lv X, Elhai JD, Wang L. Anger as an underlying dimension of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2018; 267:535-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.011] [PMID]

- De Berardis D, Vellante F, Fornaro M, Anastasia A, Olivieri L, Rapini G, et al. Alexithymia, suicide ideation, affective temperaments and homocysteine levels in drug naïve patients with post-traumatic stress disorder: An exploratory study in the everyday ‘real world’clinical practice. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2020; 24(1):83-7. [DOI:10.1080/13651501.2019.1699575] [PMID]

- Zerach G, Solomon Z. A relational model for the intergenerational transmission of captivity trauma: A 23-year longitudinal study. Psychiatry. 2016; 79(3):297-316. [DOI:10.1080/00332747.2016.1142775] [PMID]

- Friedman MJ, Resick PA, Bryant RA, Brewin CR. Considering PTSD for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety. 2011; 28(9):750-69. [DOI:10.1002/da.20767] [PMID]

- Kanani K, Hadi S, Tayebi NP. [The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on treating the adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder after road accidents in the province of Isfahan (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2015; 1(2):22-32. [Link]

- Perlick DA, Sautter FJ, Becker-Cretu JJ, Schultz D, Grier SC, Libin AV, et al. The incorporation of emotion-regulation skills into couple-and family-based treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder. Military Medical Research. 2017; 4:21. [DOI:10.1186/s40779-017-0130-9] [PMID]

- Horowitz MJ. Stress response syndromes: PTSD, grief, adjustment, and dissociative disorders. Maryland: Jason Aronson, Incorporated; 2011. [Link]

- Shrira A, Mollov B, Mudahogora C. Complex PTSD and intergenerational transmission of distress and resilience among Tutsi genocide survivors and their offspring: A preliminary report. Psychiatry Research. 2019; 271:121-3. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.040] [PMID]

- Passardi S, Peyk P, Rufer M, Wingenbach TSH, Pfaltz MC. Facial mimicry, facial emotion recognition and alexithymia in post-traumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019; 122:103436. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103436] [PMID]

- Woidneck MR, Morrison KL, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress among adolescents. Behavior Modification. 2014; 38(4):451-76. [DOI:10.1177/0145445513510527] [PMID]

- Putica A, Van Dam NT, Steward T, Agathos J, Felmingham K, O’Donnell M. Alexithymia in post-traumatic stress disorder is not just emotion numbing: Systematic review of neural evidence and clinical implications. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021; 278:519-27. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.100] [PMID]

- Merati A, Veiskarami HA, Avand D. [The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy on improving post-traumatic stress disorder (case study: People affected by the earthquake, Kermanshah 2017). (Persian)] Quarterly Scientific Journal of Rescue and Relief. 2018; 10(2):90-100. [Link]

- Shearer J, Papanikolaou N, Meiser-Stedman R, McKinnon A, Dalgleish T, Smith P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cognitive therapy as an early intervention for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A trial based evaluation and model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2018; 59(7):773-80. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12851] [PMID]

- Moghtadayi M, Khosh Akhlagh H. Effectiveness of acceptance-and commitment-based therapy on psychological flexibility of veterans’ spouses. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health. 2015; 7(4):183-8. [Link]

- Walser RD, Westrup D. Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma-related problems: A practitioner’s guide to using mindfulness and acceptance strategies. California: New Harbinger Publications; 2007. [Link]

- World Health Organization. Life skills education for children and adolescents in schools: Introduction and Guidelines to facilitate the development and implementation of life skills programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [Link]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy. 2011; 42(4):676-88. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007] [PMID]

- Kazemi A. [The effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive strategies training in reducing the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and the psychological problems of spouses of people with post-traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. Thought and Behavior in Clinical Psychology (Thought and Behavior). 2012; 6(23):31-42. [Link]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004; 26:41-54. [DOI:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Inannual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 1993 Oct 24; San Antonio, TX. [Link]

- Tran GQ, Smith GP. Behavioral assessment in the measurement of treatment outcome. In: Haynes SN, Heiby EM, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment. Vol. 3. Behavioral assessment. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. [Link]

- Arjmand K, Mahmoud Alilo M, Khanjani Z, Bakhshipour A. [The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in reducing craving in methamphetamine addict patients: An experimental study (Persian)]. Studies in Medical Sciences. 2019; 30(3):217-28. [Link]

- Ardeshiri F, Sharifi T. [Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on self-concept and emotional regulation of children with learning disabilities (Persian)]. Journal of Child Mental Health. 2019; 6(3):28-39. [DOI:10.29252/jcmh.6.3.4]

- Rahbar Karbasdehi E, Abolghasemi A, Hossein Khanzadeh AA, Rahbar Karbasdehi F. [The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment-based therapy on cognitive regulation of emotion and existential anxiety in patients with multiple sclerosis (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology and Personality. 2020; 18(2):1-9. [Link]

- Zakiei A, Khazaie H, Rostampour M, Lemola S, Esmaeili M, Dürsteler K, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) improves sleep quality, experiential avoidance, and emotion regulation in individuals with insomnia-results from a randomized interventional study. Life. 2021; 11(2):133. [DOI:10.3390/life11020133] [PMID]

- Spidel A, Lecomte T, Kealy D, Daigneault I. Acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis and trauma: Improvement in psychiatric symptoms, emotion regulation, and treatment compliance following a brief group intervention. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2018; 91(2):248-61. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12159] [PMID]

- Blackledge JT, Hayes SC. Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001; 57(2):243-55. [PMID]

- Gross JJ. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Publications; 2013. [Link]

- Ghadampour E, Heidaryani L, Bafrooeii M. [The effectiveness of quality of life therapy on psychological well-being, resiliency, marital satisfaction in wives of veterans (Persian)]. Journal of Military Medicine. 2019; 21(1):22-31. [Link]

- Falahati M, Shafiabady A, Jajarmi M, Mohamadipoor M. [Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and logotherapy on marital satisfaction of veterans’ spouses (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health. 2019; 11(3):139-45. [DOI:10.29252/ijwph.11.3.139]

- Ghorbani V, Zanjani Z, Omidi A, Sarvizadeh M. Efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on depression, pain acceptance, and psychological flexibility in married women with breast cancer: A pre-and post-test clinical trial. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2021; 43(2):126-33. [DOI:10.47626/2237-6089-2020-0022] [PMID]

- Wersebe H, Lieb R, Meyer AH, Hofer P, Gloster AT. The link between stress, well-being, and psychological flexibility during an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy self-help intervention. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2018; 18(1):60-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.09.002] [PMID]

- Paliliunas D, Belisle J, Dixon MR. A randomized control trial to evaluate the use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to increase academic performance and psychological flexibility in graduate students. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018; 11(3):241-53. [DOI:10.1007/s40617-018-0252-x] [PMID]

- Meyer EC, Kotte A, Kimbrel NA, DeBeer BB, Elliott TR, Gulliver SB, et al. Predictors of lower-than-expected posttraumatic symptom severity in war veterans: The influence of personality, self-reported trait resilience, and psychological flexibility. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019; 113:1-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2018.12.005] [PMID]

- Isa Nejad A, Azadbakht F. Comparison of the effectiveness of two approaches of acceptance, commitment and cognitive therapy based on mindfulness on quality of life and resilience of spouses of veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) caused by war. Journal of Military Psychology. 2019; 1(38):69-57. [Link]

- Molavi P, Pourabdol S, Azarkolah A. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on posttraumatic cognitions and psychological inflexibility among students with trauma exposure. Archives of Trauma Research. 2020; 9(2):69-74. [Link]

- Razavi Sadati SF, Makvandi B, Pasha R, Hosseini SH. [Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) on thought control strategy and quality of life in veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health. 2018; 10(3):115-20. [DOI:10.29252/ijwph.10.3.115]

- Hermann BA, Meyer EC, Schnurr PP, Batten SV, Walser RD. Acceptance and commitment therapy for co-occurring PTSD and substance use: A manual development study. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2016; 5(4):225-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2016.07.001]

- Casselman RB, Pemberton JR. ACT-based parenting group for veterans with PTSD: Development and preliminary outcomes. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2015; 43(1):57-66. [DOI:10.1080/01926187.2014.939003]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2023/07/24 | Accepted: 2023/12/21 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2023/07/24 | Accepted: 2023/12/21 | Published: 2024/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |