Sun, Nov 16, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 30, Issue 1 (Continuously Updated 2024)

IJPCP 2024, 30(1): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hosseini Fayyaz M B, Atef Vahid M K, Asgharnejad Farid A. Effectiveness of a Multisystemic Therapy-based Intervention in Treating Non-suicidal Self-injury Behaviors and Conduct Problems in a Male Adolescent: A Case Report. IJPCP 2024; 30 (1) : 4600.1

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3935-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3935-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health -Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Health Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health -Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,atefvahid.mk@iums.ac.ir

3- Department of Mental Health, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health -Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Health Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health -Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Mental Health, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health -Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 2957 kb]

(882 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2201 Views)

Full-Text: (648 Views)

Introduction

Conduct disorder (CD) is a severe mental disorder in children and adolescents that is characterized by recurrent and persistent violation of the rights of others or social norms [1]. It is estimated that there are 51.1 million patients with CD in the world [2]. According to the epidemiological studies, the CD prevalence is 2-16% [1, 3, 4]. The non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is another common mental health problem among adolescents. According to previous studies, NSSI is a common comorbid problem with CD in adolescents [5-8]. The prevalence of NSSI behaviors among patients with CD is 15.5-62.5% [9], which increased during the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. The annual cost of CD and NSSI are substantial [11-13], and there is a crucial need for efficient and cost-effective interventions to treat them.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) was originally developed to treat juvenile offenders with severe conduct problems and their families [14]. During the past two decades, MST has been adapted and applied in various settings for treating adolescents with NSSI behaviors [15]. No study in Iran has investigated the effectiveness of MST in treating NSSI behaviors and CD simultaneously. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the feasibility of applying MST-based intervention (MST-BI) as an unprecedented therapeutic intervention in treating CD symptoms associated with NSSI behaviors.

Methods

Case report

The case was a 17-year-old boy who met the criteria for CD and NSSI behaviors using the structured clinical interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th ed. (DSM-IV) [19]. He was a tenth-grade student and the first child of a family with three children who was living with his single-parent mother at the time of the study. He had two younger sisters (aged 9 and 7 years), one had attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the other was diagnosed with autism. He was referred for treatment because of frequent aggressive behaviors at home and at school, school truancy, relationship with deviant peers. and persistent NSSI behaviors. His interactions with family members were highly conflictual –especially with his mother. Another major problem was that he often violated home curfew and his mother often did not know his whereabouts. His mother had married twice, and the case was her child from her first marriage that ended in divorce. His step-father had recently died of cardiac arrest. According to the case and his mother, the mother had authoritarian parenting style and constantly expected complete obedience from her son and even once had used physical punishment. The constant struggle between the mother and son had resulted in emotional distance between them. It should be noted that the mother had diabetes (type II) and suffered from major depressive disorder. However, the family had not received any kind of psychosocial interventions for their psychological problems.

Measures

Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA)

This test battery consists of Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) and Teacher Report Form (TRF). Each subtest contains 113 items [20]. In the current study, we used two subscales of delinquent behaviors (or rule-breaking behaviors) and aggressive behaviors in the Persian version of ASEBA [20]. For the Persian version, internal consistency of ASEBA scales are from 0.63 to 0.95 [20].

Inventory of Statements About Self-injury (ISAS)

This inventory designed to assess NSSI behaviors in 13 functions of NSSI rated as 0 (not relevant), 1 (somewhat relevant) or 2 (very relevant) [21]. For the Persian version of ISAS, internal consistency of intrapersonal and interpersonal functions are from 0.52 to 0.79 and from 0.62 to 0.69, respectively [21].

Intervention

First, several meetings with key informants were held and semi structured interviews were conducted to complete fit factors (circles) of referral problems at the individual, family, peer, school and neighborhood levels to identify primary drivers that had significant role in sustaining CD and NSSI behaviors. Then, according to identified fit circles, the targets and goals of the intervention were determined through cooperation with the case, his mother and his school teacher. The case and his family received MST-BI for 20 weeks, 4 hours per week. At baseline (4 weeks), intervention (5 months) and follow-up (3 months) phases, the case and his mother as well as his teacher completed the YSR, CBCL and TRF, respectively [20]. Also, during these periods, the case completed the ISAS [21].

Results

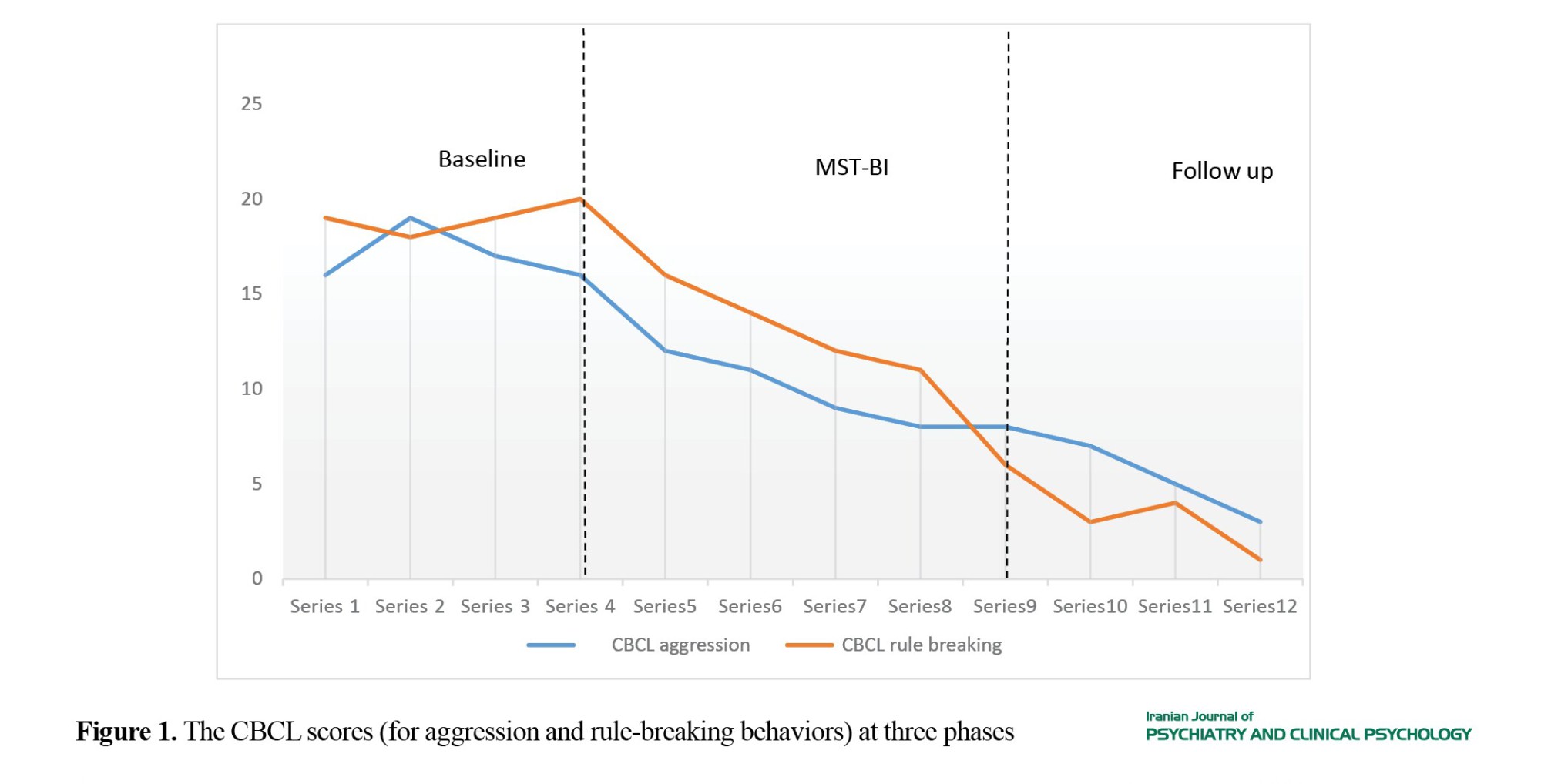

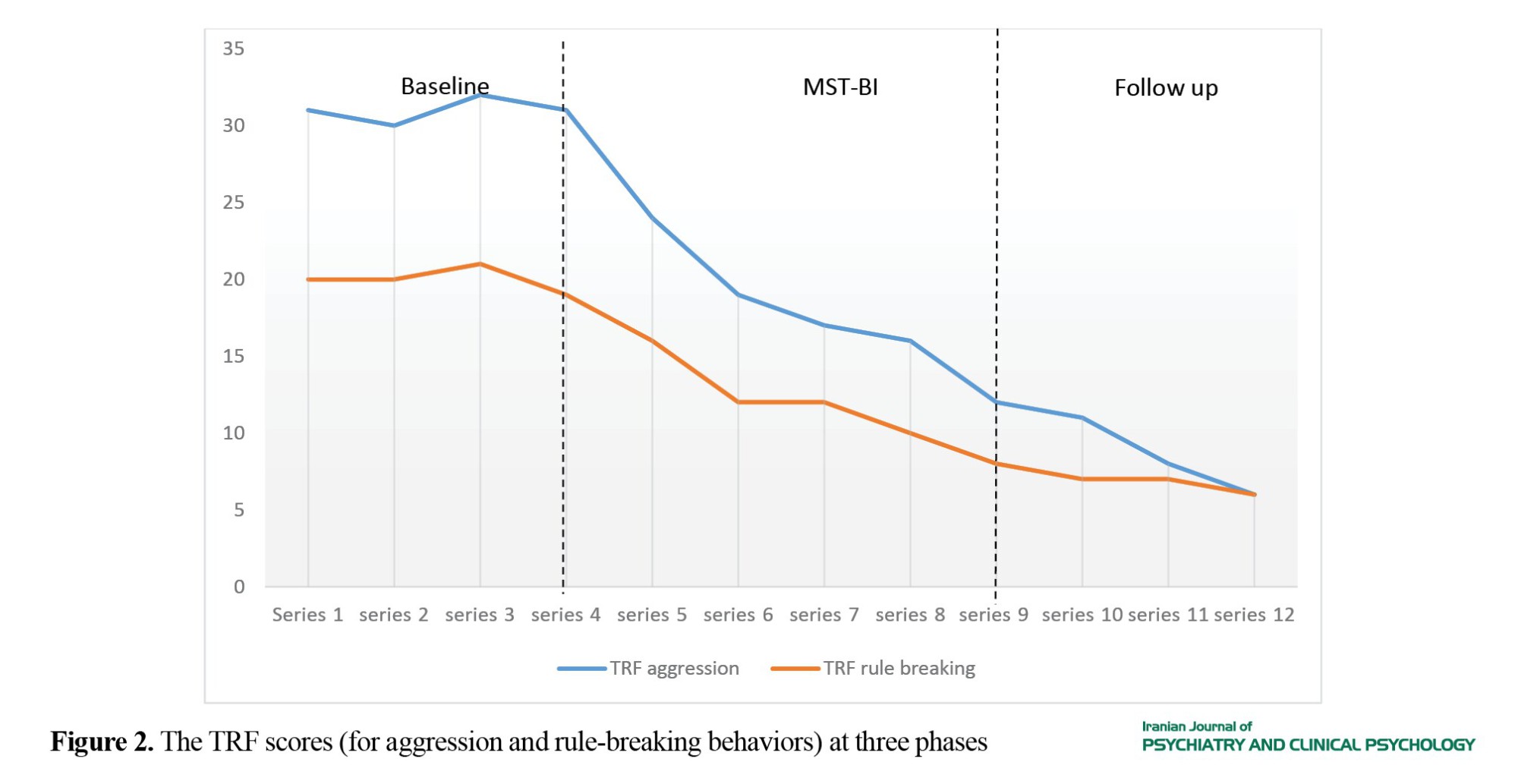

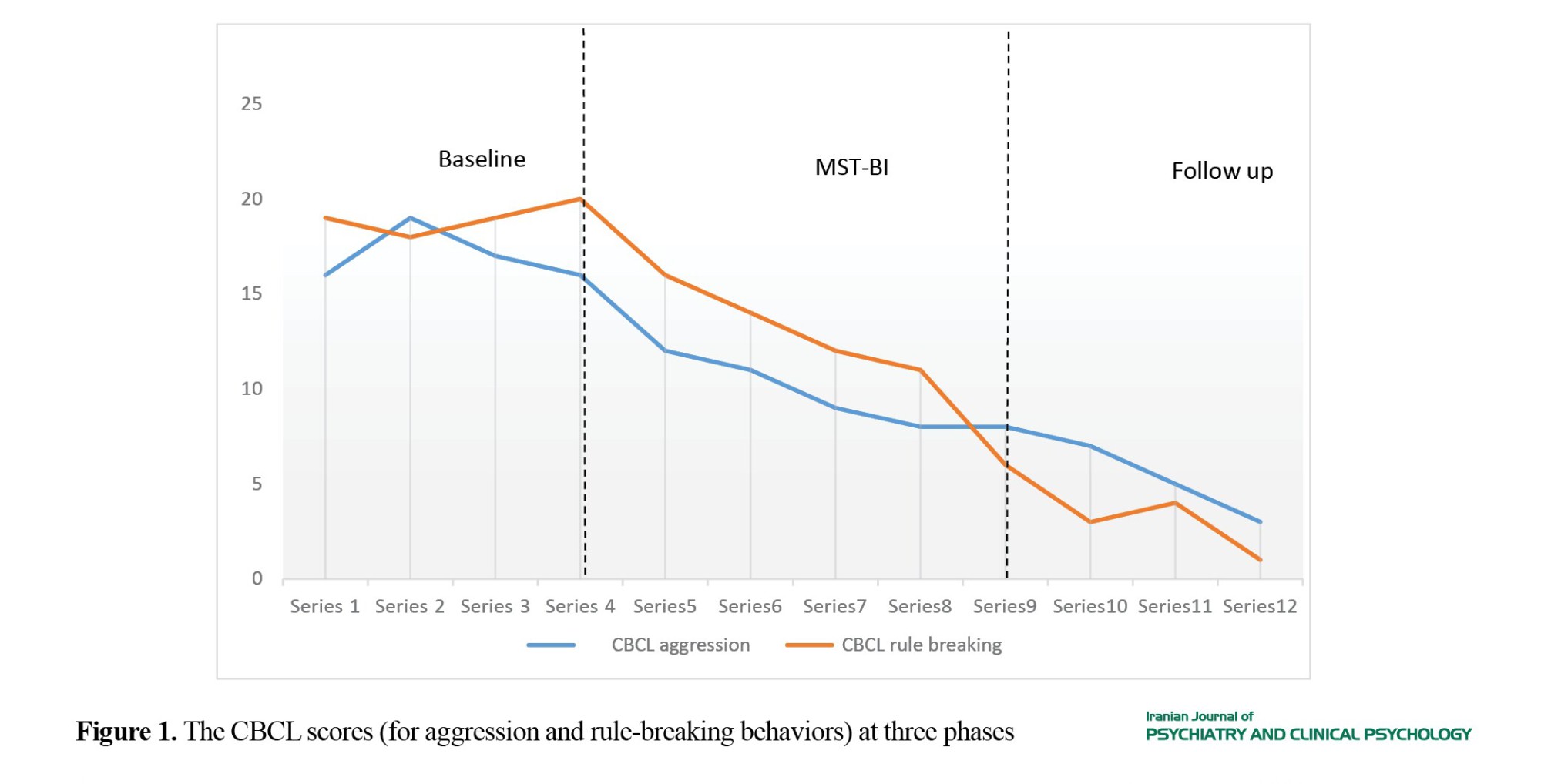

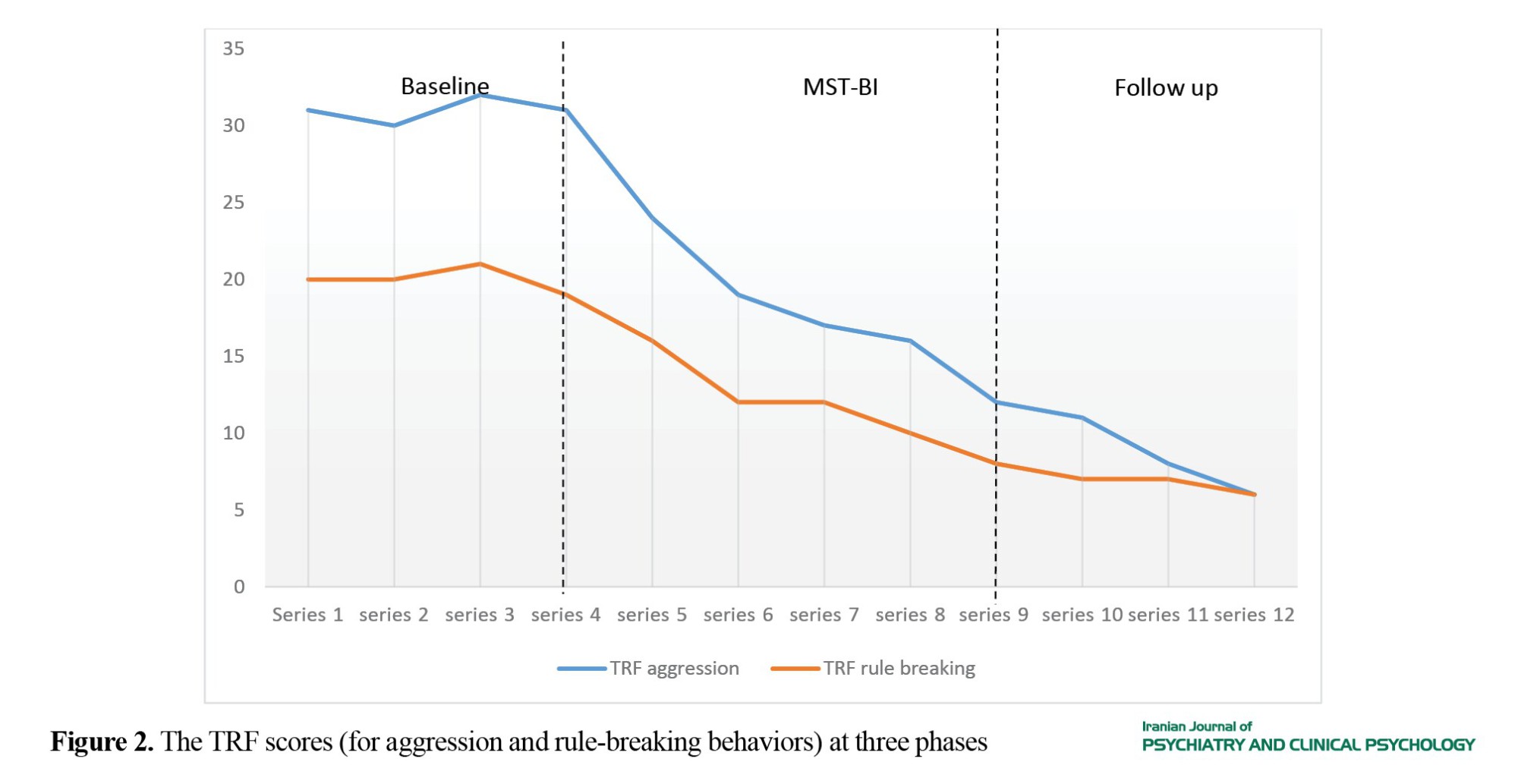

According to the reports by the case and his mother and teacher, conduct problems (aggression and rule-breaking behaviors) decreased during the intervention and follow-up phases (Figures 1 and 2).

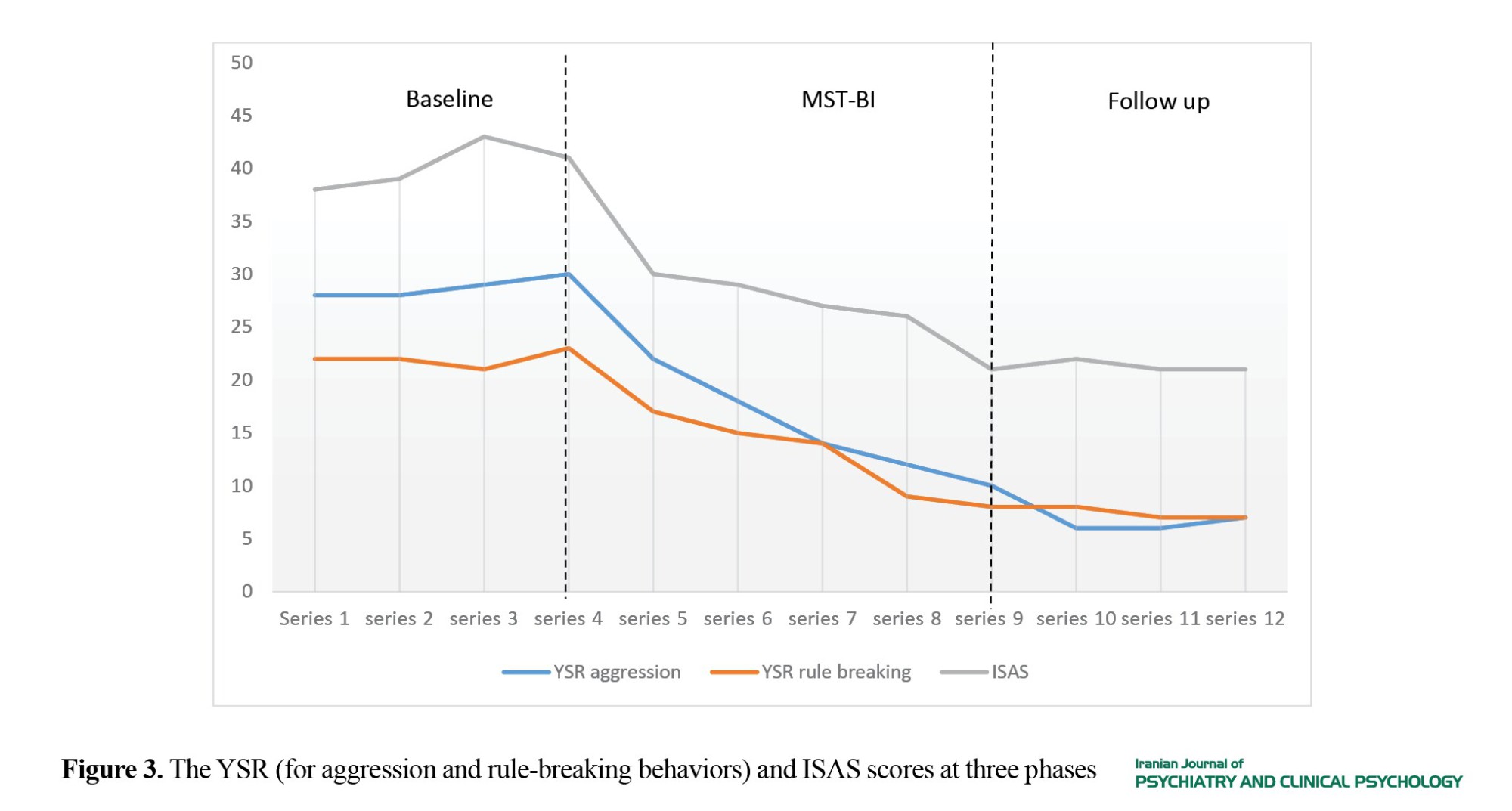

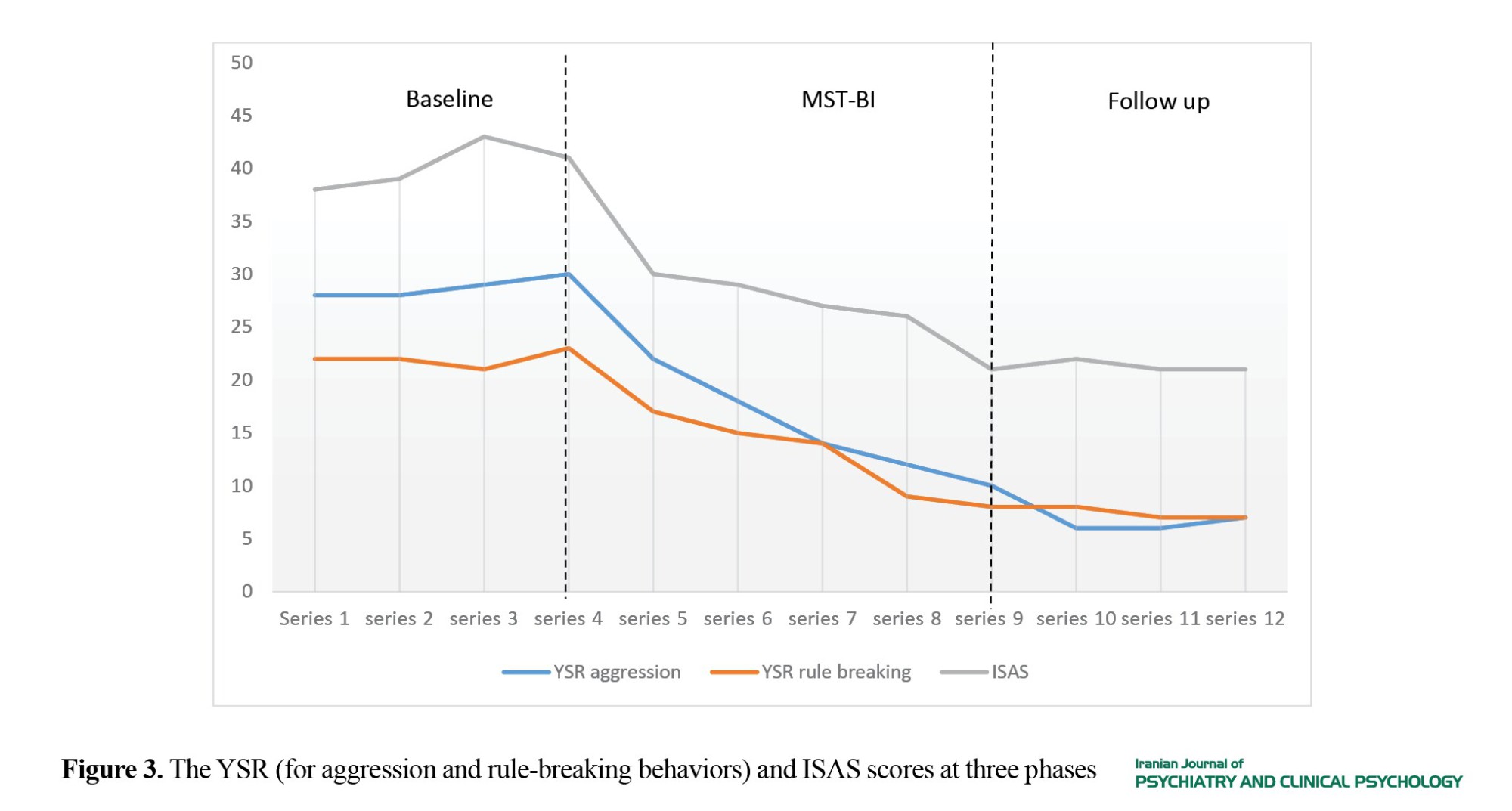

Also, according to the scores of ISAS, the NSSI behaviors decreased during the intervention and follow up phases (Figure 3).

Conclusion

The current case report should be considered as the first attempt to examine the effectiveness of MST-BI in treating the co-occurrence of NSSI behaviors and CD symptoms. The findings showed that MST-BI was effective in treating CD and NSSI behaviors in adolescents. This intervention with a focus on the common factors for effective treatments of NSSI (including addressing the family problems, skills training, treatment intensity, and NSSI risk factors) [22] and using ecological validity caused a significant reduction in the frequency of NSSI behaviors. Also, aggression and rule-breaking behaviors decreased significantly at different phases of the study reported by the mother, the teacher, and the case himself. In fact, family intervention is the main component of MST and enhancement in family relations has considerable impact on youth’s antisocial behaviors [33].

The MST-BI has the potential to significantly reduce NSSI behaviors and CD symptoms in male adolescents. As a case report, the main limitation of the present study was the short follow-up duration. More studies with experimental design, large sample sizes, and longer follow up phases (12 months or longer) are recommended to examine the efficacy of MST-BI in individuals with comorbid NSSI and CD.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1395.9021521002). Before treatment, a written informed consent was obtained from the parent.

Funding

The current study was extracted from the PhD thesis of the first author. This study was funded by Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, review & editing: All Authors; Investigation, resources, data Curation, writing original draft, visualization: Seyed Mohammad Bagher Hosseini Fayyaz; Formal analysis: Seyed Mohammad Bagher Hosseini Fayyaz and Ali-Asghar Asgharnejad Farid; Supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: Mohammad Kazem Atef Vahid; Funding: Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient, his family, and his teacher for their cooperation in this study.

Conduct disorder (CD) is a severe mental disorder in children and adolescents that is characterized by recurrent and persistent violation of the rights of others or social norms [1]. It is estimated that there are 51.1 million patients with CD in the world [2]. According to the epidemiological studies, the CD prevalence is 2-16% [1, 3, 4]. The non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is another common mental health problem among adolescents. According to previous studies, NSSI is a common comorbid problem with CD in adolescents [5-8]. The prevalence of NSSI behaviors among patients with CD is 15.5-62.5% [9], which increased during the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. The annual cost of CD and NSSI are substantial [11-13], and there is a crucial need for efficient and cost-effective interventions to treat them.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) was originally developed to treat juvenile offenders with severe conduct problems and their families [14]. During the past two decades, MST has been adapted and applied in various settings for treating adolescents with NSSI behaviors [15]. No study in Iran has investigated the effectiveness of MST in treating NSSI behaviors and CD simultaneously. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the feasibility of applying MST-based intervention (MST-BI) as an unprecedented therapeutic intervention in treating CD symptoms associated with NSSI behaviors.

Methods

Case report

The case was a 17-year-old boy who met the criteria for CD and NSSI behaviors using the structured clinical interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th ed. (DSM-IV) [19]. He was a tenth-grade student and the first child of a family with three children who was living with his single-parent mother at the time of the study. He had two younger sisters (aged 9 and 7 years), one had attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the other was diagnosed with autism. He was referred for treatment because of frequent aggressive behaviors at home and at school, school truancy, relationship with deviant peers. and persistent NSSI behaviors. His interactions with family members were highly conflictual –especially with his mother. Another major problem was that he often violated home curfew and his mother often did not know his whereabouts. His mother had married twice, and the case was her child from her first marriage that ended in divorce. His step-father had recently died of cardiac arrest. According to the case and his mother, the mother had authoritarian parenting style and constantly expected complete obedience from her son and even once had used physical punishment. The constant struggle between the mother and son had resulted in emotional distance between them. It should be noted that the mother had diabetes (type II) and suffered from major depressive disorder. However, the family had not received any kind of psychosocial interventions for their psychological problems.

Measures

Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA)

This test battery consists of Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) and Teacher Report Form (TRF). Each subtest contains 113 items [20]. In the current study, we used two subscales of delinquent behaviors (or rule-breaking behaviors) and aggressive behaviors in the Persian version of ASEBA [20]. For the Persian version, internal consistency of ASEBA scales are from 0.63 to 0.95 [20].

Inventory of Statements About Self-injury (ISAS)

This inventory designed to assess NSSI behaviors in 13 functions of NSSI rated as 0 (not relevant), 1 (somewhat relevant) or 2 (very relevant) [21]. For the Persian version of ISAS, internal consistency of intrapersonal and interpersonal functions are from 0.52 to 0.79 and from 0.62 to 0.69, respectively [21].

Intervention

First, several meetings with key informants were held and semi structured interviews were conducted to complete fit factors (circles) of referral problems at the individual, family, peer, school and neighborhood levels to identify primary drivers that had significant role in sustaining CD and NSSI behaviors. Then, according to identified fit circles, the targets and goals of the intervention were determined through cooperation with the case, his mother and his school teacher. The case and his family received MST-BI for 20 weeks, 4 hours per week. At baseline (4 weeks), intervention (5 months) and follow-up (3 months) phases, the case and his mother as well as his teacher completed the YSR, CBCL and TRF, respectively [20]. Also, during these periods, the case completed the ISAS [21].

Results

According to the reports by the case and his mother and teacher, conduct problems (aggression and rule-breaking behaviors) decreased during the intervention and follow-up phases (Figures 1 and 2).

Also, according to the scores of ISAS, the NSSI behaviors decreased during the intervention and follow up phases (Figure 3).

Conclusion

The current case report should be considered as the first attempt to examine the effectiveness of MST-BI in treating the co-occurrence of NSSI behaviors and CD symptoms. The findings showed that MST-BI was effective in treating CD and NSSI behaviors in adolescents. This intervention with a focus on the common factors for effective treatments of NSSI (including addressing the family problems, skills training, treatment intensity, and NSSI risk factors) [22] and using ecological validity caused a significant reduction in the frequency of NSSI behaviors. Also, aggression and rule-breaking behaviors decreased significantly at different phases of the study reported by the mother, the teacher, and the case himself. In fact, family intervention is the main component of MST and enhancement in family relations has considerable impact on youth’s antisocial behaviors [33].

The MST-BI has the potential to significantly reduce NSSI behaviors and CD symptoms in male adolescents. As a case report, the main limitation of the present study was the short follow-up duration. More studies with experimental design, large sample sizes, and longer follow up phases (12 months or longer) are recommended to examine the efficacy of MST-BI in individuals with comorbid NSSI and CD.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1395.9021521002). Before treatment, a written informed consent was obtained from the parent.

Funding

The current study was extracted from the PhD thesis of the first author. This study was funded by Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, review & editing: All Authors; Investigation, resources, data Curation, writing original draft, visualization: Seyed Mohammad Bagher Hosseini Fayyaz; Formal analysis: Seyed Mohammad Bagher Hosseini Fayyaz and Ali-Asghar Asgharnejad Farid; Supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: Mohammad Kazem Atef Vahid; Funding: Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient, his family, and his teacher for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5: A quick glance. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013; 55(3):220-3. [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.117131] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015; 386(9995):743-800. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Green H, McGinnity Á, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. Green H, editor. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005. [Link]

- Mandel HP. Conduct disorder and underachievement: Risk factors, assessment, treatment, and prevention. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. [Link]

- Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2014; 44(3):273-303. [DOI:10.1111/sltb.12070] [PMID]

- Zetterqvist M, Jonsson LS, Landberg Å, Svedin CG. A potential increase in adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury during covid-19: A comparison of data from three different time points during 2011 - 2021. Psychiatry Research. 2021; 305:114208. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114208] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Meszaros G, Horvath LO, Balazs J. Self-injury and externalizing pathology: A systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry. 2017; 17(1):160. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-017-1326-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shooshtari MH, Khanipour H. Comparison of self-harm and suicide attempt in adolescents: A systematic review. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2014; 20(1):3-13. [Link]

- Ilomäki E, Räsänen P, Viilo K, Hakko H; STUDY-70 Workgroup. Suicidal behavior among adolescents with conduct disorder--the role of alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Research. 2007; 150(3):305-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.02.011] [PMID]

- Du N, Ouyang Y, Xiao Y, Li Y. Psychosocial factors associated with increased adolescent non-suicidal self-injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021; 12:743526. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.743526] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hauber K, Boon A, Vermeiren R. Non-suicidal Self-Injury in Clinical Practice. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019; 10:502. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00502] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Glenn CR, Lanzillo EC, Esposito EC, Santee AC, Nock MK, Auerbach RP. Examining the course of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in outpatient and inpatient adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2017; 45(5):971-83. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-016-0214-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rissanen E, Kuvaja-Köllner V, Elonheimo H, Sillanmäki L, Sourander A, Kankaanpää E. The long-term cost of childhood conduct problems: Finnish nationwide 1981 birth cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2022; 63(6):683-92. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.13506] [PMID]

- Henggeler SW. Multisystemic therapy: Clinical foundations and research outcomes. Psychosocial Intervention. 2012; 21(2):181-93. [DOI:10.5093/in2012a12]

- Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins C, Sheidow AJ, Ward DM, Randall J, et al. One-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy as an alternative to the hospitalization of youths in psychiatric crisis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003; 42(5):543-51. [PMID]

- Fox KR, Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Kleiman EM, Bentley KH, Nock MK. Meta-analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015; 42:156-67. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Schoenwald SK, Ward DM, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD. Multisystemic therapy versus hospitalization for crisis stabilization of youth: Placement outcomes 4 months postreferral. Mental Health Services Research. 2000; 2(1):3-12. [DOI:10.1023/A:1010187706952] [PMID]

- Huey SJ Jr, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Pickrel SG, et al. Multisystemic therapy effects on attempted suicide by youths presenting psychiatric emergencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004; 43(2):183-90. [DOI:10.1097/00004583-200402000-00014] [PMID]

- Amini H, Sharifi V, Asaadi SM, Mohammadi MR, Kaviani H, Semnani Y, et al. [Validity of the Iranian version of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) In the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders (Persian)]. Payesh. 2008; 7(1):49-57. [Link]

- Minaee A. [Adaptation and standardization of child behavior checklist, youth self-report, and teacher’s report forms (Persian)]. Journal of Exceptional Children. 2006; 6(1):529-58. [Link]

- Rezaei O, Athar ME, Ebrahimi A, Jazi EA, Karimi S, Ataie S, et al. Psychometric properties of the persian version of the inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 2021; 8(1):27. [DOI:10.1186/s40479-021-00168-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015; 44(1):1-29. [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2014.945211] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Suyemoto KL. The functions of self-mutilation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998; 18(5):531-54. [DOI:10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00105-0] [PMID]

- Byrne S, Morgan S, Fitzpatrick C, Boylan C, Crowley S, Gahan H, et al. Deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents: A qualitative study exploring the needs of parents and carers. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008; 13(4):493-504. [DOI:10.1177/1359104508096765] [PMID]

- Tschan T, Lüdtke J, Schmid M, In-Albon T. Sibling relationships of female adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury disorder in comparison to a clinical and a nonclinical control group. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2019; 13:15. [DOI:10.1186/s13034-019-0275-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Littell JH, Pigott TD, Nilsen KH, Green SJ, Montgomery OL. Multisystemic Therapy® for social, emotional, and behavioural problems in youth age 10 to 17: An updated systematic review and meta‐analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2021; 17(4):e1158. [DOI:10.1002/cl2.1158]

- Martino SC, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ, McCaffrey D, Edelen MO. Multiple trajectories of physical aggression among adolescent boys and girls. Aggressive Behavior. 2008; 34(1):61-75. [DOI:10.1002/ab.20215] [PMID]

- Keijsers L, Branje S, Hawk ST, Schwartz SJ, Frijns T, Koot HM, et al. Forbidden friends as forbidden fruit: Parental supervision of friendships, contact with deviant peers, and adolescent delinquency. Child Development. 2012; 83(2):651-66. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01701.x] [PMID]

- Long N, Edwards MC, Bellando J. Parent training interventions. In: Matson JL, editor. Handbook of childhood psychopathology and developmental disabilities treatment. Berlin: Springer; 2017. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-71210-9_5]

- Vaillancourt T, Miller JL, Fagbemi J, Côté S, Tremblay RE. Trajectories and predictors of indirect aggression: results from a nationally representative longitudinal study of Canadian children aged 2-10. Aggressive Behavior. 2007; 33(4):314-26. [DOI:10.1002/ab.20202] [PMID]

- van Loon LM, Granic I, Engels RC. The role of maternal depression on treatment outcome for children with externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011; 33(2):178-86. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-011-9228-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dodge KA, Prinstein MJ. Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Publications; 2008. [Link]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic therapy for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Publications; 2009. [Link]

Type of Study: Case report |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2023/09/23 | Accepted: 2024/05/20 | Published: 2024/08/19

Received: 2023/09/23 | Accepted: 2024/05/20 | Published: 2024/08/19

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |