Wed, Jul 16, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 28, Issue 4 (Winter 2023)

IJPCP 2023, 28(4): 424-441 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Minagar F, Ahmadzad-Asl M, Tehrani Bani Hashemi A, Tayefi B, Mohabbat N, Ramezani M. Effects of Horticultural Activities on Mild to Moderate Depression Symptoms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. IJPCP 2023; 28 (4) :424-441

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3772-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3772-en.html

France Minagar1

, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl2

, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl2

, Arash Tehrani Bani Hashemi3

, Arash Tehrani Bani Hashemi3

, Batool Tayefi3

, Batool Tayefi3

, Nassim Mohabbat4

, Nassim Mohabbat4

, Mozhdeh Ramezani5

, Mozhdeh Ramezani5

, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl2

, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl2

, Arash Tehrani Bani Hashemi3

, Arash Tehrani Bani Hashemi3

, Batool Tayefi3

, Batool Tayefi3

, Nassim Mohabbat4

, Nassim Mohabbat4

, Mozhdeh Ramezani5

, Mozhdeh Ramezani5

1- Department of Community and Family Medicine, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychiatry, Sunnybrook Health Science Center, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

3- Department of Community and Family Medicine, Preventive Medicine and Public Health Research Center, Psychosocial Health Research Institute, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Agricultural-Phytomedical Engineer, Tehran Municipality Flower and Plant Education and Consulting Research Center, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Community and Family Medicine, Preventive Medicine and Public Health Research Center, Psychosocial Health Research Institute, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ramezani.m@iums.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychiatry, Sunnybrook Health Science Center, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

3- Department of Community and Family Medicine, Preventive Medicine and Public Health Research Center, Psychosocial Health Research Institute, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Agricultural-Phytomedical Engineer, Tehran Municipality Flower and Plant Education and Consulting Research Center, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Community and Family Medicine, Preventive Medicine and Public Health Research Center, Psychosocial Health Research Institute, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Depression, Ecological and environmental concepts, Gardening, Horticultural therapy, Nature

Full-Text [PDF 6704 kb]

(949 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2378 Views)

Full-Text: (725 Views)

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent health problem, often associated with comorbidities and poor health outcomes, such as decreased life expectancy [1]. Depressive disorders impose an average cost of US$ 7,638 on healthcare systems per person every year [5]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider preventive and therapeutic actions, such as environmental activities to improve the community’s physical and mental health while reducing medication use and decreasing the cost imposed on healthcare systems [6].

The nature-based therapeutic interventions involve plants and natural settings, such as tending to a garden for human health and well-being. These interventions are referred to by different terms, such as horticultural therapy, social and therapeutic horticulture, and people-plant relationships [7]. Previous studies have confirmed the positive effects of horticulture on physical health, mental health, emotional well-being, social functioning, anxiety, and depression [13-24].

To the best of our knowledge, there are inadequate RCTs regarding the effects of horticultural therapy on depression [13, 18], and most of them are limited to the elderly [14, 22] and recommended further analyses [23]. Therefore, this study, by assessing the effects of horticulture on depressed adults (not only the elderly), can fill the knowledge gap. This study aimed to determine the impact of indoor horticultural activities on mild-to-moderate depression symptoms. For this purpose, we hypothesized that the severity of depression symptoms in adults (18 years old or above) would differ between the experimental and control groups.

Methods

This research is a randomized controlled trial with two groups: (1) horticultural or experimental and (2) control groups. The statistical population included patients aged 19–66 years with mild-to-moderate depression symptoms, defined based on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) score. The computer-based randomization was performed through fourfold sampling blocks.

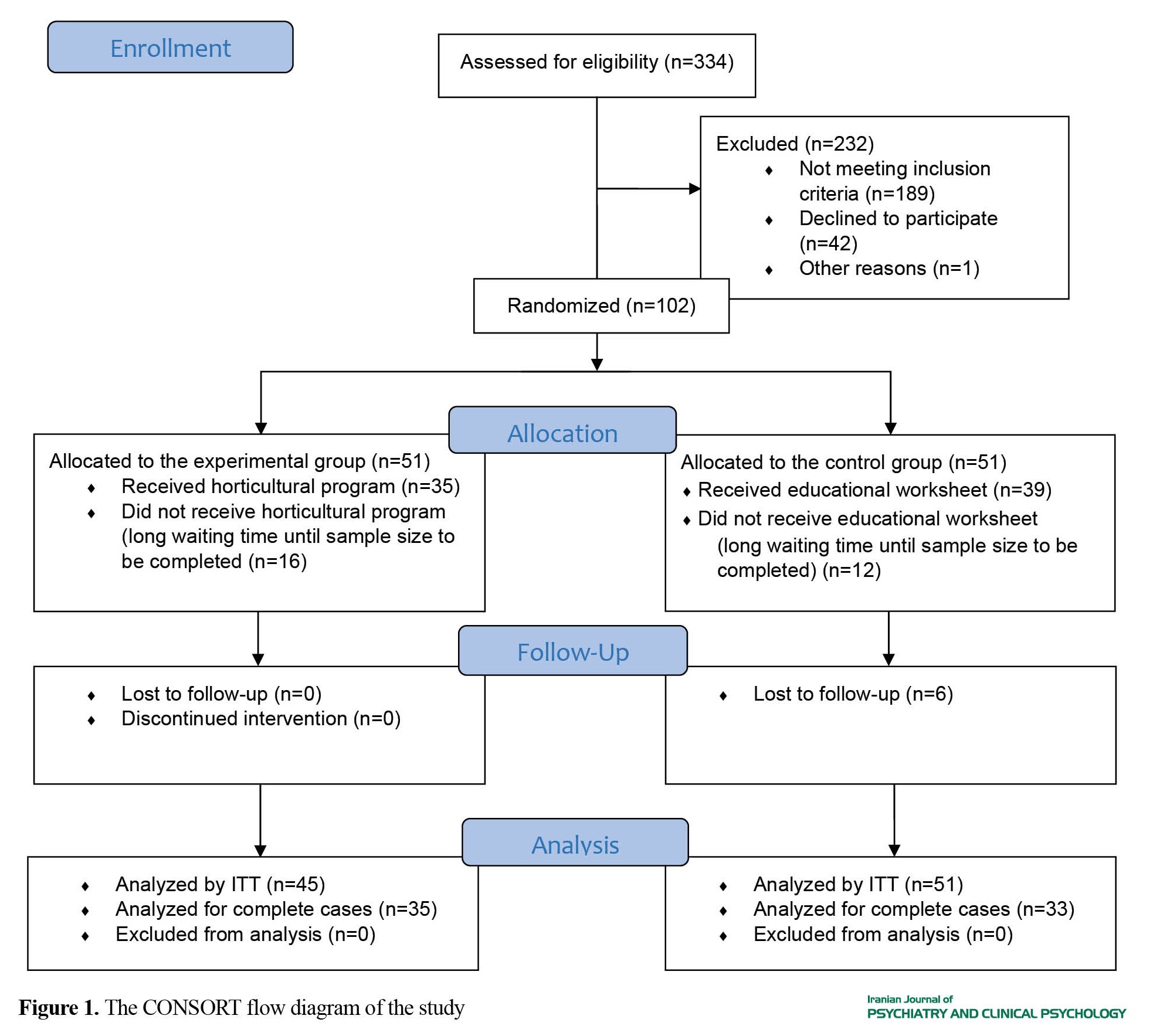

After 334 candidates were screened for the eligibility criteria, 102 eligible participants were selected and assigned randomly to the experimental and control groups (51 members each). The sample size was calculated as 80 participants (40 members each). However, this study was a group research work with a long waiting time, and some randomized participants left the study before the intervention started (16 from the experimental group and 12 from the control group) (Figure 1), which was not predicted in advance.

Depression is a prevalent health problem, often associated with comorbidities and poor health outcomes, such as decreased life expectancy [1]. Depressive disorders impose an average cost of US$ 7,638 on healthcare systems per person every year [5]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider preventive and therapeutic actions, such as environmental activities to improve the community’s physical and mental health while reducing medication use and decreasing the cost imposed on healthcare systems [6].

The nature-based therapeutic interventions involve plants and natural settings, such as tending to a garden for human health and well-being. These interventions are referred to by different terms, such as horticultural therapy, social and therapeutic horticulture, and people-plant relationships [7]. Previous studies have confirmed the positive effects of horticulture on physical health, mental health, emotional well-being, social functioning, anxiety, and depression [13-24].

To the best of our knowledge, there are inadequate RCTs regarding the effects of horticultural therapy on depression [13, 18], and most of them are limited to the elderly [14, 22] and recommended further analyses [23]. Therefore, this study, by assessing the effects of horticulture on depressed adults (not only the elderly), can fill the knowledge gap. This study aimed to determine the impact of indoor horticultural activities on mild-to-moderate depression symptoms. For this purpose, we hypothesized that the severity of depression symptoms in adults (18 years old or above) would differ between the experimental and control groups.

Methods

This research is a randomized controlled trial with two groups: (1) horticultural or experimental and (2) control groups. The statistical population included patients aged 19–66 years with mild-to-moderate depression symptoms, defined based on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) score. The computer-based randomization was performed through fourfold sampling blocks.

After 334 candidates were screened for the eligibility criteria, 102 eligible participants were selected and assigned randomly to the experimental and control groups (51 members each). The sample size was calculated as 80 participants (40 members each). However, this study was a group research work with a long waiting time, and some randomized participants left the study before the intervention started (16 from the experimental group and 12 from the control group) (Figure 1), which was not predicted in advance.

Therefore, more participants were randomized to deal with this situation and prevent the loss of research efficiency. Moreover, we ensured the intervention would impose no risks or costs on participants. Then, the remaining participants were assigned to the experimental (35 participants) and the control (39 participants) groups. Both groups received educational worksheets as a non-pharmacological treatment. Moreover, the experimental group participated in weekly horticultural program sessions for six weeks. The horticultural program included indoor floriculture and vegetable gardening performed in groups. The severity of depression symptoms was appraised at baseline, after six weeks (at the end of intervention), and after ten weeks (four weeks after the end of intervention) through the BDI-II.

Results

Data analysis was conducted through the intention-to-treat (ITT) and complete-case methods. The statistical population included 96 participants. At baseline, 38 (39.6%) out of 96 participants had mild depression, whereas 58 (60.4%) had moderate depression. The independent t-test demonstrated no significant differences between the experimental and control groups regarding the mean age and BDI scores at baseline (Table 1).

In addition, the Chi-square test results indicated no significant differences in gender, educational attainment, and depression severity between the two groups at baseline. However, there was a significant difference between the two groups concerning occupational status.

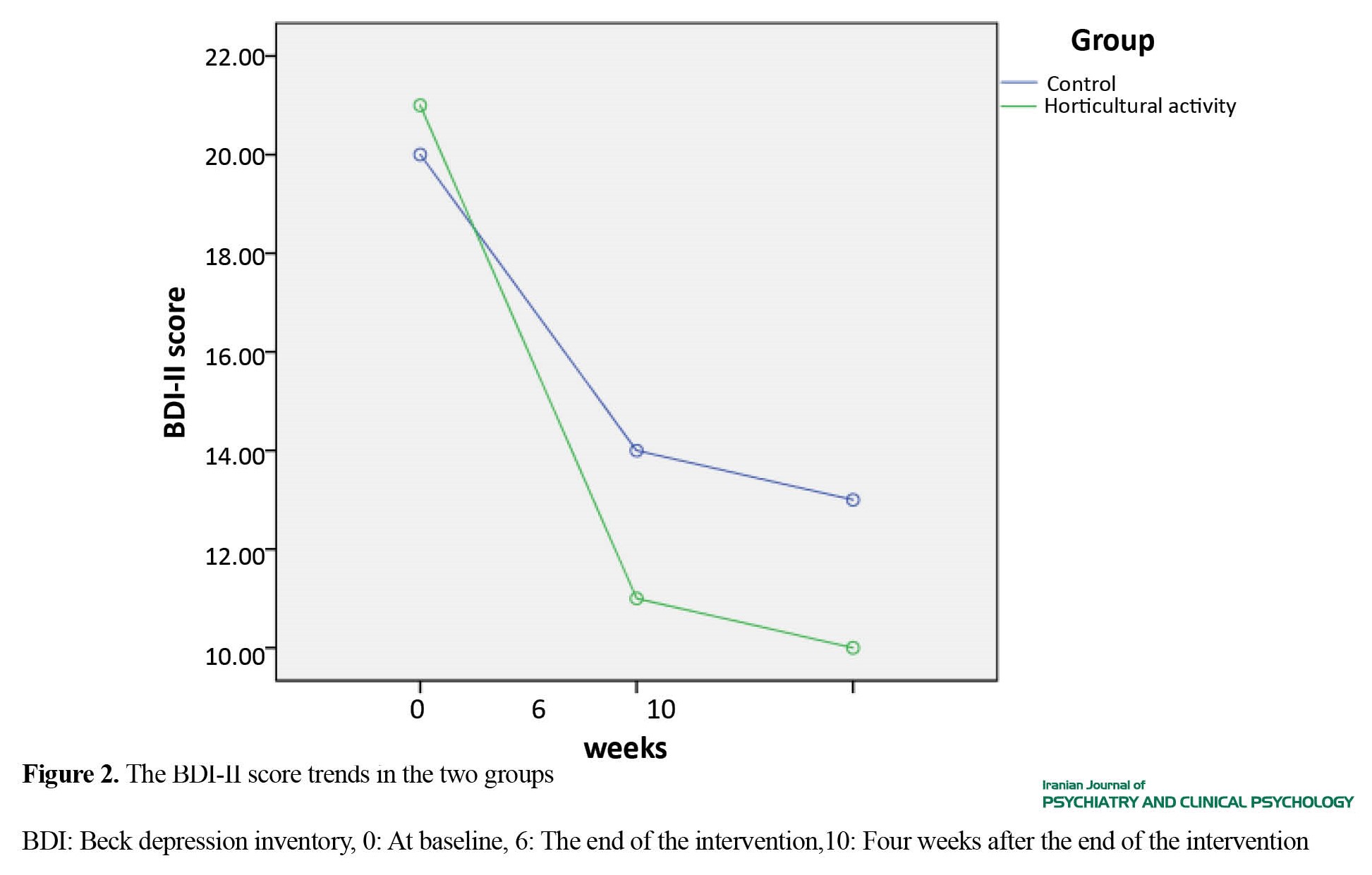

The repeated-measures ANOVA was used for data analysis by comparing changes in the BDI-II scores throughout the study, which showed lower scores among both groups at the end of the intervention and four weeks later as opposed to the baseline (Figure 2).

Results

Data analysis was conducted through the intention-to-treat (ITT) and complete-case methods. The statistical population included 96 participants. At baseline, 38 (39.6%) out of 96 participants had mild depression, whereas 58 (60.4%) had moderate depression. The independent t-test demonstrated no significant differences between the experimental and control groups regarding the mean age and BDI scores at baseline (Table 1).

In addition, the Chi-square test results indicated no significant differences in gender, educational attainment, and depression severity between the two groups at baseline. However, there was a significant difference between the two groups concerning occupational status.

The repeated-measures ANOVA was used for data analysis by comparing changes in the BDI-II scores throughout the study, which showed lower scores among both groups at the end of the intervention and four weeks later as opposed to the baseline (Figure 2).

The results revealed that the mean BDI-II scores in the horticultural group declined by 5.68 (P=0.001) and 2.32 (P=0.016) points more than the control group at the end of the intervention and four weeks later, respectively.

After the end of the intervention and four weeks later, the experimental group indicated mean reductions of 9.90 (P<0.004) and 10.27 (P<0.033) in BDI-II scores based on the ITT analysis. Moreover, the repeated-measures analysis of variance for the BDI-II score indicated the significant effect of the intervention based on the ITT analysis (F=26.73, P=0.001) and the complete-case analysis (F=14.22, P=0.001) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study reported that indoor horticultural activities might mitigate the severity of depression symptoms. However, the efficiency of this method was reduced after the cessation of horticultural activities. Regarding the factors affecting the efficiency of horticultural activities, we found that horticultural activities were more effective in moderate depression symptoms than mild symptoms. Not only does this finding indicate the most suitable target population for this therapeutic activity, but it may also raise a question regarding potential differences between mild and moderate symptoms in psychopathology. Previous observations also confirm that pharmacological and psychiatric interventions have been effective in moderate to severe depression, but they have not had a significant effect on mild depression compared to the placebo [30]. The intervention might have boosted a sense of belonging through social connections in the experimental group. Behavioral activation might also have effectively mitigated depression symptoms, such as slowness, psychomotor agitation, decreased energy, and reduced interest in pleasurable behaviors, such as interpersonal relationships. The results of this study may serve as preliminary findings to support the potential role of horticultural programs in primary healthcare centers in collaboration with other community partners, such as local greenhouses, to help improve mental health conditions in people with mild-to-moderate depression. As this study was performed in groups, it appears that social communication affected the intervention outcomes. Therefore, it is recommended to conduct studies on people with depression symptoms to evaluate the effects of horticultural therapy per se. Finally, a more robust methodology is recommended with biomarker measurements and/or functional neuroimaging in future studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1397.54) and was registered by Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20181206041871N1)

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD thesis of France Minagar and was funded by Preventive Medicine and Population Health Research Center of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: France Minagar, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl, Arash Tehrani Bani Hashemi, Batool Tayefi and Mozhdeh Ramezani; Investigation: France Minagar and Nassim Mohabbat; Project management and Supervision: France Minagar, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl and Mozhdeh Ramezani; Initial draft preparation: France Minagar; Methodology: Arash Tehrani Bani Hash-emi and Mozhdeh Ramezani; Design, Methodology, software, data curation, data analysis, val-idation, funding acquisition: Mozhdeh Ramezani; Writing, review & editing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they had no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the manages of Flower and Plant Education Center of Al-Mahdi Park in Tehran and Ms.

References

After the end of the intervention and four weeks later, the experimental group indicated mean reductions of 9.90 (P<0.004) and 10.27 (P<0.033) in BDI-II scores based on the ITT analysis. Moreover, the repeated-measures analysis of variance for the BDI-II score indicated the significant effect of the intervention based on the ITT analysis (F=26.73, P=0.001) and the complete-case analysis (F=14.22, P=0.001) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study reported that indoor horticultural activities might mitigate the severity of depression symptoms. However, the efficiency of this method was reduced after the cessation of horticultural activities. Regarding the factors affecting the efficiency of horticultural activities, we found that horticultural activities were more effective in moderate depression symptoms than mild symptoms. Not only does this finding indicate the most suitable target population for this therapeutic activity, but it may also raise a question regarding potential differences between mild and moderate symptoms in psychopathology. Previous observations also confirm that pharmacological and psychiatric interventions have been effective in moderate to severe depression, but they have not had a significant effect on mild depression compared to the placebo [30]. The intervention might have boosted a sense of belonging through social connections in the experimental group. Behavioral activation might also have effectively mitigated depression symptoms, such as slowness, psychomotor agitation, decreased energy, and reduced interest in pleasurable behaviors, such as interpersonal relationships. The results of this study may serve as preliminary findings to support the potential role of horticultural programs in primary healthcare centers in collaboration with other community partners, such as local greenhouses, to help improve mental health conditions in people with mild-to-moderate depression. As this study was performed in groups, it appears that social communication affected the intervention outcomes. Therefore, it is recommended to conduct studies on people with depression symptoms to evaluate the effects of horticultural therapy per se. Finally, a more robust methodology is recommended with biomarker measurements and/or functional neuroimaging in future studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1397.54) and was registered by Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20181206041871N1)

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD thesis of France Minagar and was funded by Preventive Medicine and Population Health Research Center of Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: France Minagar, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl, Arash Tehrani Bani Hashemi, Batool Tayefi and Mozhdeh Ramezani; Investigation: France Minagar and Nassim Mohabbat; Project management and Supervision: France Minagar, Masoud Ahmadzad-Asl and Mozhdeh Ramezani; Initial draft preparation: France Minagar; Methodology: Arash Tehrani Bani Hash-emi and Mozhdeh Ramezani; Design, Methodology, software, data curation, data analysis, val-idation, funding acquisition: Mozhdeh Ramezani; Writing, review & editing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they had no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the manages of Flower and Plant Education Center of Al-Mahdi Park in Tehran and Ms.

References

- Jia H, Lubetkin EI. Incremental decreases in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms for U.S. Adults aged 65 years and older. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2017; 15(1):9. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-016-0582-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Scientific Reports. 2018; 8(1):2861. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health. 2013; 34:119-38. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tahan M, Saleem T, Zygoulis P, Pires LVL, Pakdaman M, Taheri H, et al. A systematic review of prevalence of depression in Iranian patients. Neuropsychopharmacologia Hungarica. 2020; 22(1):16-22. [PMID]

- Ho RC, Mak KK, Chua AN, Ho CS, Mak A. The effect of severity of depressive disorder on economic burden in a university hospital in Singapore. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2013; 13(4):549-59. [DOI:10.1586/14737167.2013.815409] [PMID]

- Husk K, Lovell R, Cooper C, Garside R. Participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities for health and well-being in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016; 5:CD010351. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD010351]

- Nilsson K, Sangster M, Gallis C, Hartig T, de Vries S, Seeland K, et al. Forests, trees, and human health. Berlin: Springer; 2010. [DOI:10.1007/978-90-481-9806-1]

- Corazon SS, Stigsdotter UK, Moeller MS, Rasmussen SM. Nature as therapist: Integrating permaculture with mindfulness-and acceptance-based therapy in the Danish Healing Forest Garden Nacadia. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling. 2012; 14(4):335-47. [DOI:10.1080/13642537.2012.734471]

- Davis S. Development of the profession of horticultural therapy. In: Simpson SP, Straus MC, editors. Horticulture as therapy: Principles and practice. New York: Food Products Press; 1998. [Link]

- Monroe L. Horticulture therapy improves the body, mind and spirit. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture. 2015; 25(2):33-40. [Link]

- Grahn P, Bengtsson IL, Welén-Andersson L, Lavesson L, Lindfors L, Tauchnitz F, et al. Alnarp rehabilitation garden: Possible health effects from the design, from theactivities and from the therapeutic team. Paper presented at: International Approaches to Research Excellence in Landscape and Health. 21 September 2007; Edinburgh, Scotland. [Link]

- Corazon SS, Stigsdotter UK, Jensen AGC, Nilsson K. Development of the nature-based therapy concept for patients with stress-related illness at the Danish healing forest garden Nacadia. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture. 2010; 20:33-51. [Link]

- Hitter T, Kallay E, Olar LE, Ştefan R, Buta E, Chiorean S, et al. The effect of therapeutic horticulture on depression and Kynurenine pathways. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 2019; 47(3):804-12. [DOI:10.15835/nbha47311544]

- Ng KST, Sia A, Ng MKW, Tan CTY, Chan HY, Tan CH, et al. Effects of horticultural therapy on Asian older adults: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(8):1705.[DOI:10.3390/ijerph15081705] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wong GCL, Ng TKS, Lee JL, Lim PY, Chua SKJ, Tan C, et al. Horticultural therapy reduces biomarkers of immunosenescence and inflammaging in community-dwelling older adults: A feasibility pilot randomized controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology. 2021; 76(2):307-17. [DOI:10.1093/gerona/glaa271] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lee AY, Kim SO, Gim GM, Kim DS, Park SA. Care farming program for family health: A pilot study with mothers and children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 17(1):27. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17010027] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chen YM, Ji JY. Effects of horticultural therapy on psychosocial health in older nursing home residents: A preliminary study. The Journal of Nursing Research. 2015; 23(3):167-71. [DOI:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000063] [PMID]

- Kam MCY, Siu AMH. Evaluation of a horticultural activity programme for persons with psychiatric illness. The Journal of Nursing Research. 2010; 20(2):80-6. [DOI:10.1016/S1569-18611170007-9]

- Gonzalez MT, Hartig T, Patil GG, Martinsen EW, Kirkevold M. Therapeutic horticulture in clinical depression: A prospective study of active components. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010; 66(9):2002-13.[DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05383.x] [PMID]

- Währborg P, Petersson IF, Grahn P. Nature-assisted rehabilitation for reactions to severe stress and/or depression in a rehabilitation garden: Long-term follow-up including comparisons with a matched population-based reference cohort. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2014; 46(3):271-6. [DOI:10.2340/16501977-1259] [PMID]

- Nicholas SO, Giang AT, Yap PLK. The effectiveness of horticultural therapy on older adults: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2019; 20(10):1351.e1-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.021] [PMID]

- Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, Makino K, Nakakubo S, Liu-Ambrose T, et al. Exercise and horticultural programs for older adults with depressive symptoms and memory problems: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 9(1):99. [DOI:10.3390/jcm9010099] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Clatworthy J, Hinds J, Camic PM. Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review. Mental Health Review Journal. 2013; 18(4):214-25. [DOI:10.1108/MHRJ-02-2013-0007]

- Kamioka H, Tsutani K, Yamada M, Park H, Okuizumi H, Honda T, et al. Effectiveness of horticultural therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2014; 22(5):930-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctim.2014.08.009] [PMID]

- Soga M, Gaston KJ, Yamaura Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016; 5:92-9.[DOI:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.007] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck depression inventory–II. Psychological Assessment. 1996. [DOI:10.1037/t00742-000]

- Jackson-Koku G. Beck depression inventory. Occupational Medicine. 2016; 66(2):174-5. [DOI:10.1093/occmed/kqv087] [PMID]

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck depression inventory--second edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depression and Anxiety. 2005; 21(4):185-92. [DOI:10.1002/da.20070] [PMID]

- Shakeri M, Parhoon H, Mohammadkhani SH, Hassani J, Parhoon K. [Effectiveness of meta-cognitive therapy on depressive symptoms and quality of life of patients with major depression disorder (Persian)]. Journal of North Khorasan. 2015; 7(2):235-65. [DOI:10.29252/jnkums.7.2.253]

- Cuijpers P, Noma H, Karyotaki E, Vinkers CH, Cipriani A, Furukawa TA. A network meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and their combination in the treatment of adult depression. World Psychiatry. 2020; 19(1):92-107. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20701] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Jabbari M, Shahidi S, Mootabi F. [Effectiveness of group intervention based on positive psychology in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety and increasing life satisfaction in adolescent girls (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psycology. 2015; 20(4):287-96. [Link]

- Husain SF, Yu R, Tang TB, Tam WW, Tran B, Quek TT, et al. Validating a functional near-infrared spectroscopy diagnostic paradigm for Major Depressive Disorder. Scientific Reports. 2020; 10(1):9740. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-66784-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zhang Z, Olszewska-Guizzo A, Husain SF, Bose J, Choi J, Tan W, et al. Brief relaxation practice induces significantly more prefrontal cortex activation during arithmetic tasks comparing to viewing greenery images as revealed by functional near-infrared spectroscopy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8366. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17228366] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2022/08/21 | Accepted: 2023/02/27 | Published: 2023/03/14

Received: 2022/08/21 | Accepted: 2023/02/27 | Published: 2023/03/14

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |