Sun, Jun 8, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 27, Issue 4 (Winter 2022)

IJPCP 2022, 27(4): 536-555 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Wah M T. Anxiety Symptoms Associated With the Severity of Problematic Smartphone Use: The Mediating Role of COVID-19 Anxiety. IJPCP 2022; 27 (4) :536-555

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3470-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3470-en.html

Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China. , matszwah@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 5232 kb]

(1104 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3393 Views)

Full-Text: (1198 Views)

1. Introduction

Background on COVID-19 pandemic

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is regarded as the biggest global health crisis in recent decades, which has already caused an enormous psychological [1] and economic [2] impact on over half of the world’s countries and regions. Different forms of lockdown, quarantine, and social distancing have been implemented across most countries affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. These infection control strategies have changed key life domains, affecting personal mobility, interpersonal relationships, and occupational activities [3].

These changes in major life domains resemble the functional impairment consequential to emotional distress and place many people at greater risk of psychiatric conditions. For example, among a large sample of Chinese (n=5033), 35% had experienced significant psychological distress and the prevalence of anxiety or depression or both was 20.4% during the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Another sample (n=3480) collected at the initial stage of COVID-19 in Spain showed 21.6% reported probable anxiety, and 18.7% probable depression [5]. Prevalence of probable anxiety and depression was associated with absence of new preventive routines, such as using a face mask when they go out and disruption to regular daily routines, such as healthy eating, sleep, and leisure activities in large population-representative samples of a region [6]. Meanwhile, perceived effective social distancing and lower the negative impact of COVID-19 were associated with more positive and less negative feelings amongst Italians (n=9) [7]. Therefore COVID-19 not only represents a major priority and challenge for the public health and healthcare systems, but also from the mental health perspective.

Problematic smartphone use and mental health

Smartphone use can improve substantial productivity and increase social capital advantages [8]. The COVID-19 pandemic and associated social distancing have widely increased the usage of the smartphone to receive COVID-19-related information in society in the past year [9]. However, the relationship between smartphone use and adaptive functioning represents an inverted U-curve, which implied that excessive use has deleterious consequences [8]. The interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model is one of the prominent theoretical frameworks explaining excessive internet and smartphone use [10]. More specifically, I-PACE conceptualizes major categories of variables influencing excessive internet use, including background predisposing variables and affective and cognitive responses. Consequences from predisposing variables involve affective and cognitive response variables, including coping, attention bias, mood dysregulation, and responses to environmental stressors. I-PACE model conceptualizes response variables as mechanisms, by which predisposing variables influence excessive internet use [10].

Problematic smartphone use (PSPU) is defined as extreme levels of use resulting in functional problems, such as social, work, or academic impairment, with symptoms resembling those in substance use disorders [11]. Many previous studies have shown that PSPU was associated with poorer physical and mental health and higher levels of depression and anxiety [12]. Negative affectivity has been investigated in relation to PSPU since excessive smartphone and internet use are conceptualized as maladaptive emotional coping processes for relieving negative affect [13, 14]. Recent studies support additional negative affectivity correlates of PSPU severity, including negative rumination [12], worry [14], and fear of missing out on rewarding social experiences [13]. It has been shown that in the current outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, PSPU is an important clinical concern, even though it is not an official mental disorder.

The present study

COVID-19 is a potentially fatal disease, and its consequential social isolation from quarantine and distancing increase anxiety [1]. Moreover, home quarantine and social distancing have widely increased the usage of smartphone to receive the COVID-19-related information [9]. Given that social isolation drives emotional distress and negative affect [6], general anxiety, as well as anxiety specific to COVID-19, should, in turn, exacerbate PSPU [12]. The current study investigated the impact of general anxiety symptoms and COVID-19-induced anxiety on the severity of PSPU as a maladaptive emotion coping method. In particular, general anxiety symptom was hypothesized as a predisposing predictor variable from I-PACE. COVID-19-induced anxiety was modeled as an ongoing response to an environmental stressor, and mediator within the affective/cognitive response category. Our dependent variable was PSPU severity.

2. Methods

Participants and procedure

Following approval from the university’s ethics committee, a cross-sectional web-based survey was conducted between July 23 and August 25, 2020 (the period of the third wave outbreak of COVID-19 in Hong Kong). Adults aged 18–75 years were recruited by stratified, probability sampling from a database representative of the population [15]. Inclusion criteria were Chinese ethnicity, Cantonese fluency (the most commonly spoken Chinese language and the mother tongue of 90% of the Hong Kong population), and elementary education level or above. Individuals with histories of psychiatric conditions and the presence of cognitive impairments were excluded from the study.

Upon obtaining potential participants’ initial verbal consent, researchers confirmed their eligibility, explained the nature of the study and obtained their written informed consent. This study consisted of 1080 participants (Mean±SD age 44.06± 16.74 years), and around half of them (n=575, 53.24%) were female. Fifty-five cases (5.09%) received primary education, 486 cases (45%) received secondary education, and 539 cases (49.91%) received tertiary education or above. Reported average monthly household income ranged from ≤HK $10,000 (10.09%), $10,001–$20,000 (18.89%), $20,001–$30,000 (19.07%), $30,001–$40,000 (22.13%), to >$40,000 (29.81%), with US $1 approximately equivalent to HK $7.80. Of the 1080 participants, 591 cases (54.72%) reported being full-time employed, 295 cases (27.31%) reported being part-time employed, 28 cases (2.59%) reported being unemployed, 56 cases (5.19%) reported that they were housewives, and 110 cases (10.19%) reported that they were retired. The results are summarized in Table 1.

.jpg)

2. Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

A standardized proforma was used to obtain demographic information, including age in years, sex, marital status, education level, employment status, and monthly household income. It was also used to obtain comorbidity status about whether participants reported the 13 common medically chronic conditions: arthritis, bladder disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, hearing problems, heart attack, hemorrhoids, hypertension, nephrolith, stroke, visual problems, cognitive problems, and any type of psychiatric disorders.

General anxiety symptoms

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) assessed psychological symptoms over the past week. It is a 21-item self-report instrument that uses a Likert-type scale from “0=Did not apply to me at all” to “3=Applied to me very much, or most of the time.” Only the anxiety subscale (7 items) was used in the current study. The Chinese instrument version was also found to have high reliability and validity previously [16]. Alpha for the anxiety subscale was 0.79 for our sample.

COVID-19-induced anxiety

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) assessed anxiety and worry symptoms over the past two weeks [17]. It is a 7-item self-report measure that uses a Likert-type frequency scale from “0=Not at all” to “3=Nearly every day.” The Chinese version was used, which was found to be reliable and valid [18]. We tailored instructions to query COVID-19-induced anxiety, specifying “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems because of the coronavirus outbreak?” The alpha for this scale was 0.90 for our sample.

Problematic smartphone use

The Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV) assessed smartphone-related problematic use and functional impairment [19]. It is a 10-item self-report measure, which was developed in Korean and English. The measure uses a Likert-type scale from “1=Strongly disagree” to “6=Strongly agree.” The Chinese SAS-SV was used, which was validated by Luk et al. [20]. The alpha for this scale was 0.89 for our sample.

Analytic plan

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for major variables using SPSS 26.0. The web survey prompted participants to complete skipped items; thus, no missing item-level data were present. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to evaluate the fitness of the hypothesized model in explaining the associations between general anxiety symptoms, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and the severity of PSPU. A two-step approach to SEM was used to examine the hypothesized relationships among the latent variables [21]. A measurement model was examined with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to determine whether the factor structure of the variables fits the data. The latent variables of general anxiety symptoms, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and severity of PSPU were indicated by their corresponding items. It was then followed by the mediation model through analyzing the direct and indirect effects among the independent and dependent variables. The goodness-of-fit of the models was evaluated using Chi-square (χ2) statistics, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values above 0.90 indicate acceptable model fit [22]. RMSEA values of 0.06 or less are considered a close model fit [22]. Amos 22.0 was used to analyze the data.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among major variables

The skewness and kurtosis statistics did not indicate problems of non-normality among the major variables. As hypothesized, general anxiety was associated with higher COVID-19-induced anxiety (r=0.44) and higher PSPU severity (r=0.36). COVID-19-induced anxiety was positively associated with PSPU severity (r=0.30). The results are summarized in Table 2.

.jpg)

We also examined the association between background demographics variables and the major variables of interest (general anxiety, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and PSPU severity). We found that all background variables did not correlate significantly with the major variables of interest.

The validated cut-off scores for each instrument were adopted to identify possible mental health cases. Also, 242 participants (22.41%) were identified with moderate anxiety using a DASS-21 anxiety score >5, with 69 participants (6.38%) with severe anxiety with a score >7. Moreover, 78 participants (7.22%) were identified with moderate COVID-19-induced anxiety using a GAD-7 score >9, with 25 cases (2.31%) of severe COVID-19-induced anxiety using a score >14. Finally, 516 participants (47.78%) were identified with PSPU using a SAS-SV score >31.

Latent variable measurement models

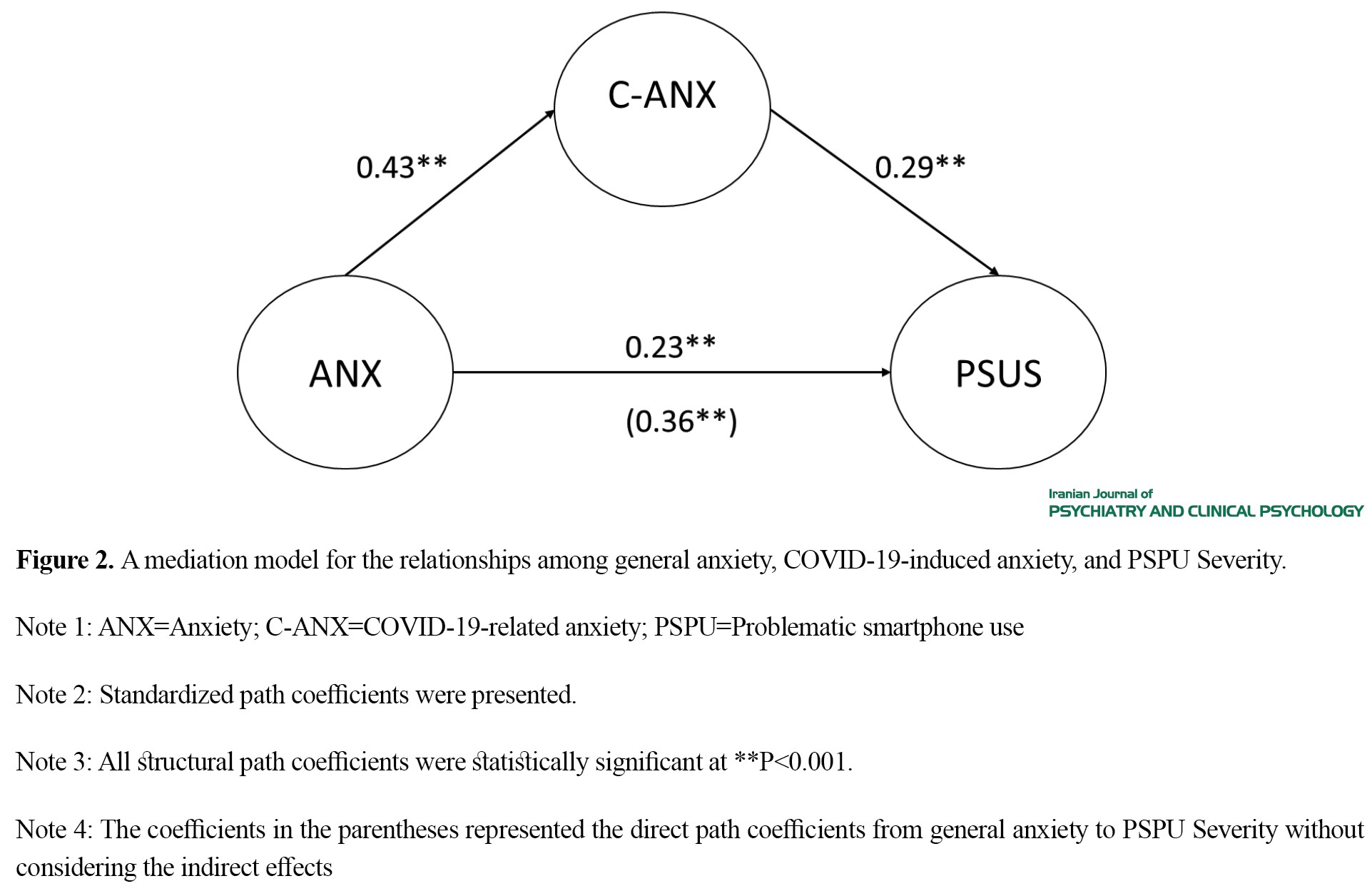

Three measurement models for latent variables were individually constructed and evaluated by CFA. The results are summarized in Figure 1. The latent variables for general anxiety symptoms, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and PSPU severity were respectively constructed by seven items, seven items, and ten items from the measurement scales. For independent variables, the measurement model for the DASS-21 anxiety subscale had a satisfactory fit (χ2 (14)=34.05, P<0.001, CFI=0.98, TLI=0.97, RMSEA=0.05). Additionally, the measurement model for the GAD-7 also had a satisfactory fit (χ2(14)=24.90, P<0.001, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.98, RMSEA=0.06). For dependent variables, the measurement model for SAS-SV had a satisfactory fit (χ2(33)=92.89, P<.001, CFI=0.95, TLI=0.93, RMSEA=0.08). The CFA results supported that those measurement models were appropriate for further testing the structural model.

Testing the mediation model

The SEM results supported fitness of the hypothesized model in predicting PSPU (χ2(100)=246.44, CFI=0.97, TLI=0.96, RMSEA=0.05), with satisfactory model fit indices. The standardized path coefficients were significant between general anxiety symptoms and COVID-19-induced anxiety (β=0.43, P<0.001) and between COVID-19-induced anxiety and PSPU severity (β=0.29, P<0.001). At the same time, the direct effect from general anxiety and PSPU severity was also significant (β=0.23, P<0.001). The results suggested that individuals with higher general anxiety symptoms tended to report more COVID-19 anxiety and have higher PSPU severity. Those having higher levels of COVID-19-induced anxiety were more likely to report higher PSPU severity. Results from bootstrapping supported the presence of a significant mediation effect. Both the indirect effects from anxiety to PSPU via COVID-19-induced anxiety (β=.12; 95% CI=0.03, 0.21) and the direct effects from anxiety to PSPU were significant (β=0.36; 95% CI=0.24, 0.47). These results indicated a partial mediation effect of COVID-19-induced anxiety between anxiety and PSPU (Figure 2). 4. Discussion

Our primary findings demonstrated that both general anxiety symptoms and COVID-19-induced anxiety were associated with PSPU severity and COVID-19-induced anxiety mediated relations between predisposing general anxiety with PSPU severity. We found the possible prevalence of at least moderate anxiety in around 22% of participants. These findings roughly correspond to other COVID-19 community estimates, ranging around 20% for moderate anxiety [4, 5]. Consistent with the prior literature [12], the current study found that COVID-19-induced anxiety was associated with PSPU severity in bivariate analyses and the SEM model. The relationship between COVID-19-induced anxiety with PSPU severity fits with the I-PACE conceptualization of responses to environmental stressors driving excessive Internet use to alleviate negative emotion [10]. Previous studies have shown that social isolation particularly influences negative affectivity [23]. Thus, to manage anxiety from COVID-19 and associated social isolation, especially considering home quarantine and the absence of numerous other activities, many people may engage in PSPU.

In our SEM model, when adding and controlling for general anxiety as predictors of PSU severity, COVID-19-induced anxiety still is related to PSU. Thus, while COVID-19-induced anxiety on its own (in SEM) was significantly related to PSU severity, controlling for general anxiety rendered this significant relationship. Despite significant concerns about COVID-19, people have other everyday life worries and anxiety (captured by our general anxiety assessment) that have not ceased but probably increased with COVID-19-induced anxiety. For example, everyday anxiety involving social and intimate relationship formation and maintenance would naturally exacerbate with home quarantine [3], and increase the fear of missing out on rewarding experiences [13]. Similarly, existing anxiety regarding finances, employment, and economic stability has risen because of the economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. Such everyday anxieties, exacerbated because of the outbreak, may supersede COVID-19-induced anxiety, resulting in adverse outcomes, such as PSPU. But, specifically fearing death from COVID-19 (from medical vulnerability, or excessive worry) may especially result in greater PSU severity to alleviate negative emotion, consistent with our findings from bivariate and SEM models.

Our study also found that COVID-19-induced anxiety mediated relations between general anxiety and PSPU severity in our mediation model. The interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model is one of the prominent theoretical frameworks explaining excessive internet and smartphone use. This model conceptualizes major categories of variables influencing excessive internet use, including background predisposing variables and affective and cognitive responses. Therefore, the findings in the current study implied that how individuals response to environment stressors is crucial on explaining the excessive smartphone use, which is consistent with I-PACE model. [10, 11]. Anxiety and worry are known to cause greater COVID-19-induced anxiety from a viral outbreak, especially among those with health anxiety misinterpreting physical sensations as viral symptoms [24]. Therefore, people with pre-existing anxiety may excessively worry about COVID-19, driving overwhelming demand for medical services [25]. It is implied that achieving the right balance between promoting social distancing, and not excessive worry, is important. Meanwhile, it is plausible that there is a feedback loop, by which people manage their COVID-19-induced anxiety by excessively using their smartphones, but by doing this, they inadvertently learn more about COVID-19 from news, further fueling their anxiety and increased smartphone use. More frequent social media exposure to COVID-19 has been shown to be positively associated with anxiety symptoms [26].

Despite significant concerns about COVID-19, people have other everyday-life worries and general anxiety symptoms that have not ceased but probably increased with COVID-19 anxiety. For example, everyday anxiety involving social and intimate relationship formation and maintenance would naturally exacerbate with home quarantine [3], and increase the fear of missing out on rewarding experiences [13]. Similarly, existing anxiety regarding finances, employment, and economic stability has risen because of the economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. Such everyday anxieties, exacerbated because of the outbreak, may supersede COVID-19-induced anxiety, resulting in adverse outcomes, such as PSPU.

Limitations and Conclusion

The research reported in our paper has several limitations. First, the data in this study were collected cross-sectionally, and hence, causal interpretations cannot be made. It is plausible that there is a feedback loop, by which people manage their COVID-19-induced anxiety by excessively using their smartphones, but by doing this, they inadvertently learn more about COVID-19 from the news, further fueling their anxiety and increased smartphone use. More frequent social media exposure to COVID-19 has been shown to be positively associated with anxiety symptoms [27]. Second, online self-report scales were used instead of the in-person interview due to the COVID-19 and the quarantine policy from the government. Relatively, structured in-person interviews would be more accurate. Additionally, we used self-reported problematic smartphone use, while future studies could consider adopting the objective measurement, such as experience sampling of the momentary mental health status and smartphone use, which is more accurate [28]. Future directions may also include other psychological outcomes, such as depressive symptoms. Nonetheless, our results provide initial data on the mental health status of people affected by COVID-19, and the relations between COVID-19-induced anxiety and PSPU severity as a coping mechanism. These results provide a foundation from, which we and other researchers can pursue further investigation of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on smartphone use generally and in the context of developing strategies to reduce COVID-19-related PSPU.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Author has complied with American Psychological Association (APA) ethical standards in the treatment of their sample, human or animal, or to describe the details of treatment.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Background on COVID-19 pandemic

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is regarded as the biggest global health crisis in recent decades, which has already caused an enormous psychological [1] and economic [2] impact on over half of the world’s countries and regions. Different forms of lockdown, quarantine, and social distancing have been implemented across most countries affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. These infection control strategies have changed key life domains, affecting personal mobility, interpersonal relationships, and occupational activities [3].

These changes in major life domains resemble the functional impairment consequential to emotional distress and place many people at greater risk of psychiatric conditions. For example, among a large sample of Chinese (n=5033), 35% had experienced significant psychological distress and the prevalence of anxiety or depression or both was 20.4% during the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Another sample (n=3480) collected at the initial stage of COVID-19 in Spain showed 21.6% reported probable anxiety, and 18.7% probable depression [5]. Prevalence of probable anxiety and depression was associated with absence of new preventive routines, such as using a face mask when they go out and disruption to regular daily routines, such as healthy eating, sleep, and leisure activities in large population-representative samples of a region [6]. Meanwhile, perceived effective social distancing and lower the negative impact of COVID-19 were associated with more positive and less negative feelings amongst Italians (n=9) [7]. Therefore COVID-19 not only represents a major priority and challenge for the public health and healthcare systems, but also from the mental health perspective.

Problematic smartphone use and mental health

Smartphone use can improve substantial productivity and increase social capital advantages [8]. The COVID-19 pandemic and associated social distancing have widely increased the usage of the smartphone to receive COVID-19-related information in society in the past year [9]. However, the relationship between smartphone use and adaptive functioning represents an inverted U-curve, which implied that excessive use has deleterious consequences [8]. The interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model is one of the prominent theoretical frameworks explaining excessive internet and smartphone use [10]. More specifically, I-PACE conceptualizes major categories of variables influencing excessive internet use, including background predisposing variables and affective and cognitive responses. Consequences from predisposing variables involve affective and cognitive response variables, including coping, attention bias, mood dysregulation, and responses to environmental stressors. I-PACE model conceptualizes response variables as mechanisms, by which predisposing variables influence excessive internet use [10].

Problematic smartphone use (PSPU) is defined as extreme levels of use resulting in functional problems, such as social, work, or academic impairment, with symptoms resembling those in substance use disorders [11]. Many previous studies have shown that PSPU was associated with poorer physical and mental health and higher levels of depression and anxiety [12]. Negative affectivity has been investigated in relation to PSPU since excessive smartphone and internet use are conceptualized as maladaptive emotional coping processes for relieving negative affect [13, 14]. Recent studies support additional negative affectivity correlates of PSPU severity, including negative rumination [12], worry [14], and fear of missing out on rewarding social experiences [13]. It has been shown that in the current outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, PSPU is an important clinical concern, even though it is not an official mental disorder.

The present study

COVID-19 is a potentially fatal disease, and its consequential social isolation from quarantine and distancing increase anxiety [1]. Moreover, home quarantine and social distancing have widely increased the usage of smartphone to receive the COVID-19-related information [9]. Given that social isolation drives emotional distress and negative affect [6], general anxiety, as well as anxiety specific to COVID-19, should, in turn, exacerbate PSPU [12]. The current study investigated the impact of general anxiety symptoms and COVID-19-induced anxiety on the severity of PSPU as a maladaptive emotion coping method. In particular, general anxiety symptom was hypothesized as a predisposing predictor variable from I-PACE. COVID-19-induced anxiety was modeled as an ongoing response to an environmental stressor, and mediator within the affective/cognitive response category. Our dependent variable was PSPU severity.

2. Methods

Participants and procedure

Following approval from the university’s ethics committee, a cross-sectional web-based survey was conducted between July 23 and August 25, 2020 (the period of the third wave outbreak of COVID-19 in Hong Kong). Adults aged 18–75 years were recruited by stratified, probability sampling from a database representative of the population [15]. Inclusion criteria were Chinese ethnicity, Cantonese fluency (the most commonly spoken Chinese language and the mother tongue of 90% of the Hong Kong population), and elementary education level or above. Individuals with histories of psychiatric conditions and the presence of cognitive impairments were excluded from the study.

Upon obtaining potential participants’ initial verbal consent, researchers confirmed their eligibility, explained the nature of the study and obtained their written informed consent. This study consisted of 1080 participants (Mean±SD age 44.06± 16.74 years), and around half of them (n=575, 53.24%) were female. Fifty-five cases (5.09%) received primary education, 486 cases (45%) received secondary education, and 539 cases (49.91%) received tertiary education or above. Reported average monthly household income ranged from ≤HK $10,000 (10.09%), $10,001–$20,000 (18.89%), $20,001–$30,000 (19.07%), $30,001–$40,000 (22.13%), to >$40,000 (29.81%), with US $1 approximately equivalent to HK $7.80. Of the 1080 participants, 591 cases (54.72%) reported being full-time employed, 295 cases (27.31%) reported being part-time employed, 28 cases (2.59%) reported being unemployed, 56 cases (5.19%) reported that they were housewives, and 110 cases (10.19%) reported that they were retired. The results are summarized in Table 1.

.jpg)

2. Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

A standardized proforma was used to obtain demographic information, including age in years, sex, marital status, education level, employment status, and monthly household income. It was also used to obtain comorbidity status about whether participants reported the 13 common medically chronic conditions: arthritis, bladder disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, hearing problems, heart attack, hemorrhoids, hypertension, nephrolith, stroke, visual problems, cognitive problems, and any type of psychiatric disorders.

General anxiety symptoms

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) assessed psychological symptoms over the past week. It is a 21-item self-report instrument that uses a Likert-type scale from “0=Did not apply to me at all” to “3=Applied to me very much, or most of the time.” Only the anxiety subscale (7 items) was used in the current study. The Chinese instrument version was also found to have high reliability and validity previously [16]. Alpha for the anxiety subscale was 0.79 for our sample.

COVID-19-induced anxiety

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) assessed anxiety and worry symptoms over the past two weeks [17]. It is a 7-item self-report measure that uses a Likert-type frequency scale from “0=Not at all” to “3=Nearly every day.” The Chinese version was used, which was found to be reliable and valid [18]. We tailored instructions to query COVID-19-induced anxiety, specifying “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems because of the coronavirus outbreak?” The alpha for this scale was 0.90 for our sample.

Problematic smartphone use

The Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV) assessed smartphone-related problematic use and functional impairment [19]. It is a 10-item self-report measure, which was developed in Korean and English. The measure uses a Likert-type scale from “1=Strongly disagree” to “6=Strongly agree.” The Chinese SAS-SV was used, which was validated by Luk et al. [20]. The alpha for this scale was 0.89 for our sample.

Analytic plan

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for major variables using SPSS 26.0. The web survey prompted participants to complete skipped items; thus, no missing item-level data were present. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to evaluate the fitness of the hypothesized model in explaining the associations between general anxiety symptoms, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and the severity of PSPU. A two-step approach to SEM was used to examine the hypothesized relationships among the latent variables [21]. A measurement model was examined with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to determine whether the factor structure of the variables fits the data. The latent variables of general anxiety symptoms, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and severity of PSPU were indicated by their corresponding items. It was then followed by the mediation model through analyzing the direct and indirect effects among the independent and dependent variables. The goodness-of-fit of the models was evaluated using Chi-square (χ2) statistics, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values above 0.90 indicate acceptable model fit [22]. RMSEA values of 0.06 or less are considered a close model fit [22]. Amos 22.0 was used to analyze the data.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among major variables

The skewness and kurtosis statistics did not indicate problems of non-normality among the major variables. As hypothesized, general anxiety was associated with higher COVID-19-induced anxiety (r=0.44) and higher PSPU severity (r=0.36). COVID-19-induced anxiety was positively associated with PSPU severity (r=0.30). The results are summarized in Table 2.

.jpg)

We also examined the association between background demographics variables and the major variables of interest (general anxiety, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and PSPU severity). We found that all background variables did not correlate significantly with the major variables of interest.

The validated cut-off scores for each instrument were adopted to identify possible mental health cases. Also, 242 participants (22.41%) were identified with moderate anxiety using a DASS-21 anxiety score >5, with 69 participants (6.38%) with severe anxiety with a score >7. Moreover, 78 participants (7.22%) were identified with moderate COVID-19-induced anxiety using a GAD-7 score >9, with 25 cases (2.31%) of severe COVID-19-induced anxiety using a score >14. Finally, 516 participants (47.78%) were identified with PSPU using a SAS-SV score >31.

Latent variable measurement models

Three measurement models for latent variables were individually constructed and evaluated by CFA. The results are summarized in Figure 1. The latent variables for general anxiety symptoms, COVID-19-induced anxiety, and PSPU severity were respectively constructed by seven items, seven items, and ten items from the measurement scales. For independent variables, the measurement model for the DASS-21 anxiety subscale had a satisfactory fit (χ2 (14)=34.05, P<0.001, CFI=0.98, TLI=0.97, RMSEA=0.05). Additionally, the measurement model for the GAD-7 also had a satisfactory fit (χ2(14)=24.90, P<0.001, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.98, RMSEA=0.06). For dependent variables, the measurement model for SAS-SV had a satisfactory fit (χ2(33)=92.89, P<.001, CFI=0.95, TLI=0.93, RMSEA=0.08). The CFA results supported that those measurement models were appropriate for further testing the structural model.

Testing the mediation model

The SEM results supported fitness of the hypothesized model in predicting PSPU (χ2(100)=246.44, CFI=0.97, TLI=0.96, RMSEA=0.05), with satisfactory model fit indices. The standardized path coefficients were significant between general anxiety symptoms and COVID-19-induced anxiety (β=0.43, P<0.001) and between COVID-19-induced anxiety and PSPU severity (β=0.29, P<0.001). At the same time, the direct effect from general anxiety and PSPU severity was also significant (β=0.23, P<0.001). The results suggested that individuals with higher general anxiety symptoms tended to report more COVID-19 anxiety and have higher PSPU severity. Those having higher levels of COVID-19-induced anxiety were more likely to report higher PSPU severity. Results from bootstrapping supported the presence of a significant mediation effect. Both the indirect effects from anxiety to PSPU via COVID-19-induced anxiety (β=.12; 95% CI=0.03, 0.21) and the direct effects from anxiety to PSPU were significant (β=0.36; 95% CI=0.24, 0.47). These results indicated a partial mediation effect of COVID-19-induced anxiety between anxiety and PSPU (Figure 2). 4. Discussion

Our primary findings demonstrated that both general anxiety symptoms and COVID-19-induced anxiety were associated with PSPU severity and COVID-19-induced anxiety mediated relations between predisposing general anxiety with PSPU severity. We found the possible prevalence of at least moderate anxiety in around 22% of participants. These findings roughly correspond to other COVID-19 community estimates, ranging around 20% for moderate anxiety [4, 5]. Consistent with the prior literature [12], the current study found that COVID-19-induced anxiety was associated with PSPU severity in bivariate analyses and the SEM model. The relationship between COVID-19-induced anxiety with PSPU severity fits with the I-PACE conceptualization of responses to environmental stressors driving excessive Internet use to alleviate negative emotion [10]. Previous studies have shown that social isolation particularly influences negative affectivity [23]. Thus, to manage anxiety from COVID-19 and associated social isolation, especially considering home quarantine and the absence of numerous other activities, many people may engage in PSPU.

In our SEM model, when adding and controlling for general anxiety as predictors of PSU severity, COVID-19-induced anxiety still is related to PSU. Thus, while COVID-19-induced anxiety on its own (in SEM) was significantly related to PSU severity, controlling for general anxiety rendered this significant relationship. Despite significant concerns about COVID-19, people have other everyday life worries and anxiety (captured by our general anxiety assessment) that have not ceased but probably increased with COVID-19-induced anxiety. For example, everyday anxiety involving social and intimate relationship formation and maintenance would naturally exacerbate with home quarantine [3], and increase the fear of missing out on rewarding experiences [13]. Similarly, existing anxiety regarding finances, employment, and economic stability has risen because of the economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. Such everyday anxieties, exacerbated because of the outbreak, may supersede COVID-19-induced anxiety, resulting in adverse outcomes, such as PSPU. But, specifically fearing death from COVID-19 (from medical vulnerability, or excessive worry) may especially result in greater PSU severity to alleviate negative emotion, consistent with our findings from bivariate and SEM models.

Our study also found that COVID-19-induced anxiety mediated relations between general anxiety and PSPU severity in our mediation model. The interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model is one of the prominent theoretical frameworks explaining excessive internet and smartphone use. This model conceptualizes major categories of variables influencing excessive internet use, including background predisposing variables and affective and cognitive responses. Therefore, the findings in the current study implied that how individuals response to environment stressors is crucial on explaining the excessive smartphone use, which is consistent with I-PACE model. [10, 11]. Anxiety and worry are known to cause greater COVID-19-induced anxiety from a viral outbreak, especially among those with health anxiety misinterpreting physical sensations as viral symptoms [24]. Therefore, people with pre-existing anxiety may excessively worry about COVID-19, driving overwhelming demand for medical services [25]. It is implied that achieving the right balance between promoting social distancing, and not excessive worry, is important. Meanwhile, it is plausible that there is a feedback loop, by which people manage their COVID-19-induced anxiety by excessively using their smartphones, but by doing this, they inadvertently learn more about COVID-19 from news, further fueling their anxiety and increased smartphone use. More frequent social media exposure to COVID-19 has been shown to be positively associated with anxiety symptoms [26].

Despite significant concerns about COVID-19, people have other everyday-life worries and general anxiety symptoms that have not ceased but probably increased with COVID-19 anxiety. For example, everyday anxiety involving social and intimate relationship formation and maintenance would naturally exacerbate with home quarantine [3], and increase the fear of missing out on rewarding experiences [13]. Similarly, existing anxiety regarding finances, employment, and economic stability has risen because of the economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. Such everyday anxieties, exacerbated because of the outbreak, may supersede COVID-19-induced anxiety, resulting in adverse outcomes, such as PSPU.

Limitations and Conclusion

The research reported in our paper has several limitations. First, the data in this study were collected cross-sectionally, and hence, causal interpretations cannot be made. It is plausible that there is a feedback loop, by which people manage their COVID-19-induced anxiety by excessively using their smartphones, but by doing this, they inadvertently learn more about COVID-19 from the news, further fueling their anxiety and increased smartphone use. More frequent social media exposure to COVID-19 has been shown to be positively associated with anxiety symptoms [27]. Second, online self-report scales were used instead of the in-person interview due to the COVID-19 and the quarantine policy from the government. Relatively, structured in-person interviews would be more accurate. Additionally, we used self-reported problematic smartphone use, while future studies could consider adopting the objective measurement, such as experience sampling of the momentary mental health status and smartphone use, which is more accurate [28]. Future directions may also include other psychological outcomes, such as depressive symptoms. Nonetheless, our results provide initial data on the mental health status of people affected by COVID-19, and the relations between COVID-19-induced anxiety and PSPU severity as a coping mechanism. These results provide a foundation from, which we and other researchers can pursue further investigation of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on smartphone use generally and in the context of developing strategies to reduce COVID-19-related PSPU.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Author has complied with American Psychological Association (APA) ethical standards in the treatment of their sample, human or animal, or to describe the details of treatment.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- McBride O, Murphy J, Shevlin M, Gibson Miller J, Hartman TK, Hyland P, et al. Monitoring the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population: An overview of the context, design and conduct of the COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2021; 30(1):e1861. [DOI:10.1002/mpr.1861] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Maital S, Barzani E. The global economic impact of COVID-19: A summary of research. Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research. 2020. https://www.neaman.org.il/EN/The-Global-Economic-Impact-of-COVID-19-A-Summary-of-Research

- Dawson DL, Golijani-Moghaddam N. COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020; 17:126-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Li J, Yang Z, Qiu H, Wang Y, Jian L, Ji J, et al. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID‐19 epidemic. World Psychiatry. 2020; 19:249-50. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20758] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Romero CS, Delgado C, Catalá J, Ferrer C, Errando C, Iftimi A, et al. COVID-19 psychological impact in 3109 healthcare workers in Spain: The PSIMCOV group. Psychological Medicin. 2020; 52(1). [DOI:10.1017/S0033291720001671] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lades LK, Laffan K, Daly M, Delaney L. Daily emotional well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2020; 25:902-11. [DOI:10.1111/bjhp.12450] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Motta-Zanin G, Gentile E, Parisi A, Spasiano D. A preliminary evaluation of the public risk perception related to the COVID-19 health emergency in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17:3024. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17093024] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Li L, Lin TT. Examining how dependence on smartphones at work relates to Chinese employees’ workplace social capital, job performance, and smartphone addiction. Information Development. 2018; 34(5):489-503. [DOI:10.1177/0266666917721735]

- Cohen IG, Gostin LO, Weitzner DJ. Digital smartphone tracking for COVID-19: Public health and civil liberties in tension. JAMA. 2020; 323(23):2371-2. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.8570] [PMID]

- Brand M, Wegmann E, Stark R, Müller A, Wölfling K, Robbins TW, et al. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2019; 104:1-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032] [PMID]

- Pivetta E, Harkin L, Billieux J, Kanjo E, Kuss DJ. Problematic smartphone use: An empirically validated model. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019; 100:105-17. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2019.06.013]

- Yang J, Fu X, Liao X, Li Y. Association of problematic smartphone use with poor sleep quality, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 284:112686. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112686] [PMID]

- Coco GL, Salerno L, Franchina V, La Tona A, Di Blasi M, Giordano C. Examining bi-directionality between Fear of Missing Out and problematic smartphone use. A two-wave panel study among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2020; 106:106360. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106360] [PMID]

- Horwood S, Anglim J. Problematic smartphone usage and subjective and psychological well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019; 97:44-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.028]

- Census and Statistics Department. Population Census-Summary Results [Internet]. 2011 [Updated 2021 May 24] Available from: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11200552011XXXXB0100.pdf

- Chan RC, Xu T, Huang J, Wang Y, Zhao Q, Shum DH, et al. Extending the utility of the depression anxiety stress scale by examining its psychometric properties in Chinese settings. Psychiatry Research. 2012; 200(2-3):879-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.041] [PMID]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006; 166:1092-7. [DOI:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092] [PMID]

- Zeng QZ, He YL, Liu H, Miao JM, Chen JX, Xu HN, et al. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale in screening anxiety disorders in outpatients from traditional Chinese internal department. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2013; 27(3):163-8. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-12337-001

- Kwon M, Kim DJ, Cho H, Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PloS One. 2013; 8(12):e83558. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0083558] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Luk TT, Wang MP, Shen C, Wan A, Chau PH, Oliffe J, et al. Short version of the smartphone addiction scale in Chinese adults: Psychometric properties, sociodemographic, and health behavioral correlates. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2018; 7(4):1157-65. [DOI:10.1556/2006.7.2018.105] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988; 103(3):411-23. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1-55. [DOI:10.1080/10705519909540118]

- Butler TR, Karkhanis AN, Jones SR, Weiner JL. Adolescent social isolation as a model of heightened vulnerability to comorbid alcoholism and anxiety disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016; 40(6):1202-14. [DOI:10.1111/acer.13075] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lee SA, Jobe MC, Mathis AA. Mental health characteristics associated with dysfunctional coronavirus anxiety. Psychological Medicine. 2020; 51(8):1403-4. [DOI:10.1017/S003329172000121X] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7:611-27. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0]

- Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. Plos One. 2020; 15:e0231924. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0231924] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hossain MT, Ahammed B, Chanda SK, Jahan N, Ela MZ, Islam MN. Social and electronic media exposure and generalized anxiety disorder among people during COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: A preliminary observation. Plos One 2020; 15:e0238974. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0238974] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rozgonjuk D, Levine JC, Hall BJ, Elhai JD. The association between problematic smartphone use, depression and anxiety symptom severity, and objectively measured smartphone use over one week. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018; 87:10-17. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.019]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2021/04/4 | Accepted: 2021/11/23 | Published: 2022/01/1

Received: 2021/04/4 | Accepted: 2021/11/23 | Published: 2022/01/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.jpg)