Sun, Nov 30, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 27, Issue 1 (Spring 2021)

IJPCP 2021, 27(1): 92-103 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kalsoom U, Hanifa B. Depression, Anxiety, Psychosomatic Symptoms, and Perceived Social Support in Type D and Non-type D Individuals. IJPCP 2021; 27 (1) :92-103

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3285-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3285-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women University, Peshawar, Pakistan. , dr.kalsoom@sbbwu.edu.pk

2- Department of Psychology, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women University, Peshawar, Pakistan.

2- Department of Psychology, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women University, Peshawar, Pakistan.

Full-Text [PDF 3169 kb]

(1894 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4165 Views)

Full-Text: (3339 Views)

1. Introduction

Type D personality is characterized by high scores in two areas: tending to encounter increasingly negative feelings (negative affectivity) and social inhibition of the feelings. Negative affectivity makes a person experience adverse feelings, for example, depressed mood, anxiety, outrage, and hostile feelings [1]. Conversely, emotional inhibition is characterized by maintaining a strategic distance from potential dangers ensuring social collaborations, for example, objection or absence of recompensating by others [2]. Type D personality is commonly known as a risk factor for challenging health consequences, wellbeing related to the quality of life (QOL), different types of distresses such as grief, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress [3]. Previous studies have proposed that type D personality may anticipate the onset [4] and persistence of depressive symptoms in patients with coronary illnesses [5]. Besides, the relationship between depressive symptoms and type D personality in the diabetic community and general population has also been noticed [6, 7]. A study using regression analysis on patients with heart failure demonstrated that type D personality predicts the mental and physical status of the patients [8]. Somatic Symptoms and Related Disorder (SSRD) is a person‘s tendency to understand and manifest psychological distress in physical form and to seek medical help to cure these symptoms [9]. Pain, panting, numbness, gastric issues have no clinical reasons to address. After doing a complete medical examination, one-third of symptoms remain medically unexplained [10]. A study was conducted in Iran to determine the relationship between somatic signs, mental health, and personality characteristics. The study showed a significant connection of somatic symptoms with mental health and personality characteristics [11]. A longitudinal study conducted in the Netherlands reported that individuals with somatic symptoms and related disorders with Type D personality got high scores on depression and anxiety [12]. Vogel found out the negative affectivity, Type D personality, and QOL had relationships with poor outcomes of total knee arthroplasty [13].

Social support is defined as behavioral support received from others, which served as a safeguard for many psychiatric illnesses/problems [14, 15]. There are three types of social support: 1) objective, 2) subjective, 3) utilization support. Objective support is known as available support; subjective support is defined as perceived support, which refers to contentment and satisfaction of support received from others. Support utilization is also known as enacted support, the term defined as any kind of support, e.g., emotional, physical, and informational support present [16]. Polman, Borkoles, and Nicholls [17] suggested no significant defensive role of perceived social support on psychological distress and Type D personality. While William and Wingate [18] reported a partial mediating role of social support with perceived stress and Type D personality. Another study on Type D personality may lead to low self-efficacy and social support in Type 2 diabetes mellitus in China [14].

In Pakistan, the concept of distressed personality is neither much known nor has been intensively investigated. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore the relationships between distressed personality, depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms. The study also intended to explore the mediating role of perceived social support with Type D, psychosomatic symptoms, and depressive symptoms.

2. Methods

Three hundred participants aged 18 to 40 years (Mean±SD: 22.25±2.66 years) were included in the study from different departments of Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women University and University of Peshawar. Both men (n=150) and women (n=150) equally participated in the study from March to September 2017. Personal information included age, sex, education, marital status, history of physical illness, and previous psychiatric illness. To measure distressed personality, we used a self-administered questionnaire comprising two subscales of Negative Affectivity (NA) and Social Inhibition (SI) [3]. Both subscales have 7 items scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The total score on each subscale ranges from 0 to 28, where higher scores indicate higher NA/SI. The Cronbach α reliability of the scale in the present study was calculated as 0.80. To measure depression and anxiety symptoms, we used an indigenous scale developed by Mumford et al. [19]. This scale has two subscales of depression and anxiety, each with 15 items. The α reliability values of the depression and anxiety scales in the present study were 0.80 and 0.80, respectively. The psychosomatic symptoms scale consists of 5-item self-report questions. They were scored on a 5-point Likert scale that measures headache, stomach ache, feeling of nervousness, feeling of irritation, and sleep problems. The scale shows good α reliability on the present sample as 0.87 [20]. Zimet, Powell, Farley, Werkman, and Berkoff [21] developed a multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS). A self-report questionnaire consists of 12 items with three subscales that assess support awareness from friends, family, and significant others. Each subscale has 4 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 84, with a high score indicates higher PSSS. In the present study, the Cronbach α was estimated as 0.94.

In this descriptive study, we contacted the head of different departments of Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women University and University of Peshawar (Pakistan) to explain the nature and purpose of the study. To observe ethical concerns, we assured the respondent of their anonymity and the use of the data for academic purposes only. The study participants were volunteers and have the right to withdraw from the study at any stage. The questionnaire booklet comprised the demographic information sheet, Pakistan anxiety and depression scale, psychosomatic symptoms scale, PSSS, and DS14. They were successfully administered to all participants after taking their informed consent. Based on cut-off scores obtained on DS 14, two groups were formed: Type D (n= 166) and non-Type D (n= 134) individuals. In the present study, a random cluster sampling technique was used.

3. Results

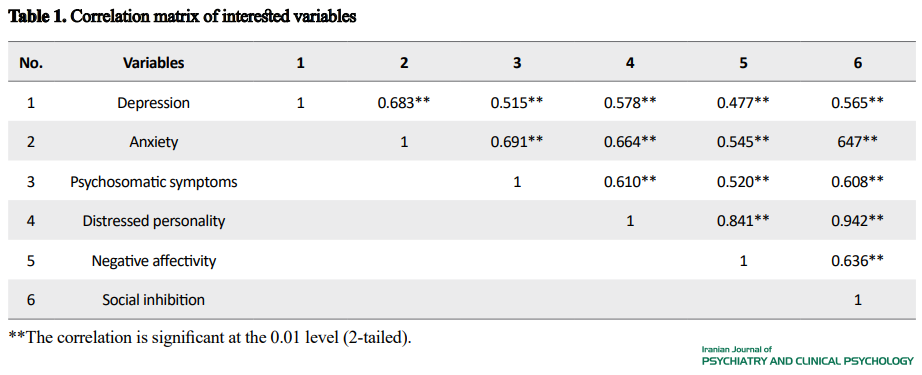

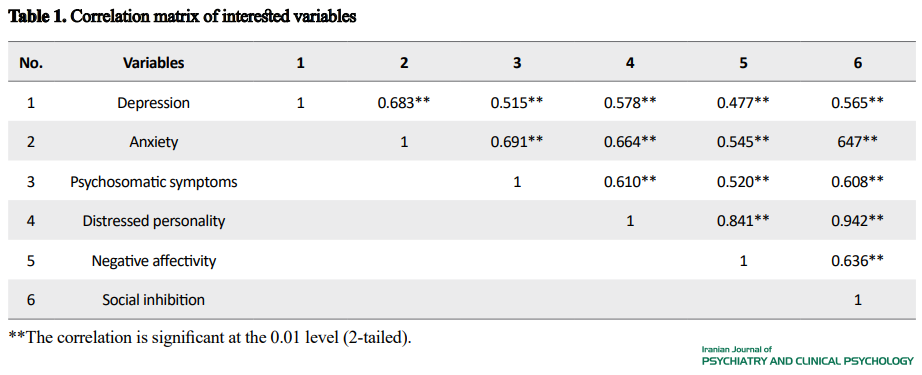

A total of 300 samples participated in the study. Among these people, 71% were 18 to 23 years old; 5% were married; 85% belonged to middle socioeconomic status, and 71% were graduate students. All variables of interest show a significant correlation at 0.01 level (Table 1).

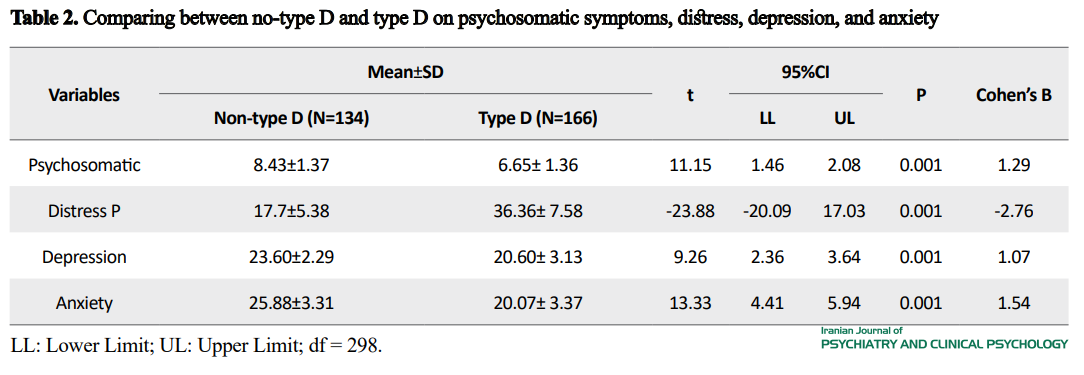

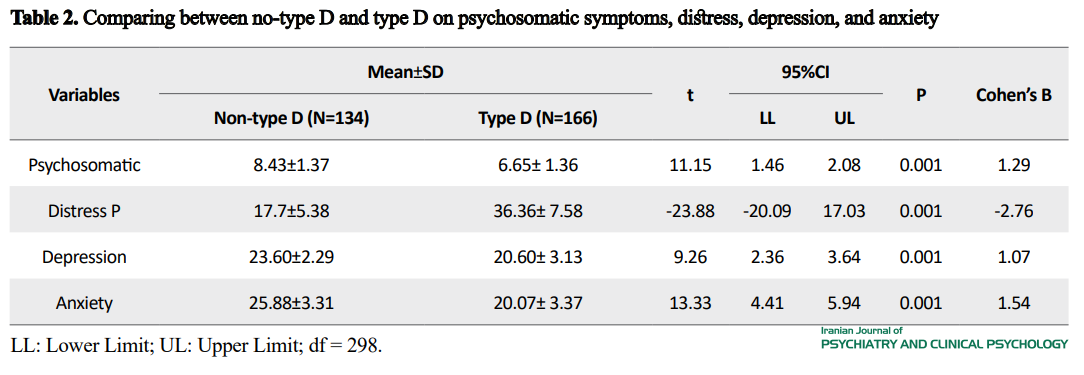

To test the study hypothesis, we performed the independent samples t-test. The results show that type D and non-Type D personalities were significantly different regarding depression, anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, and distress scale (Table 2).

To test the study hypothesis, we performed the independent samples t-test. The results show that type D and non-Type D personalities were significantly different regarding depression, anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, and distress scale (Table 2).

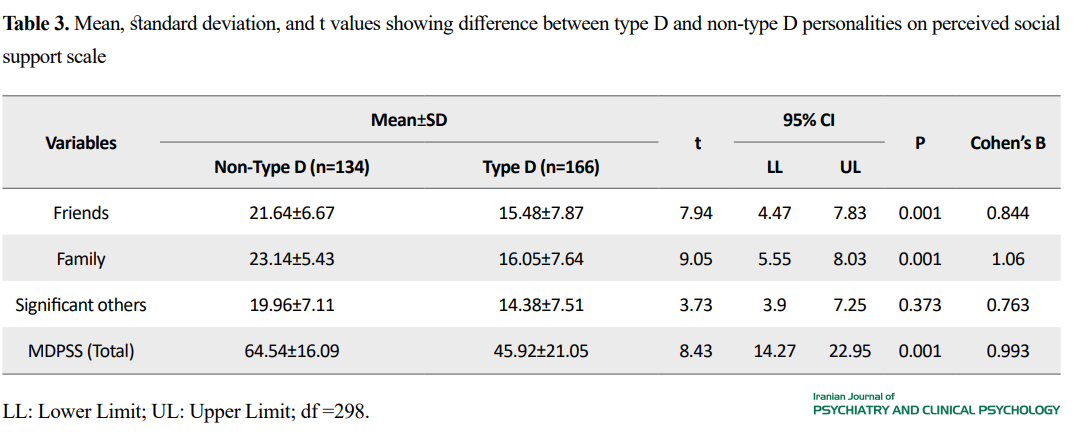

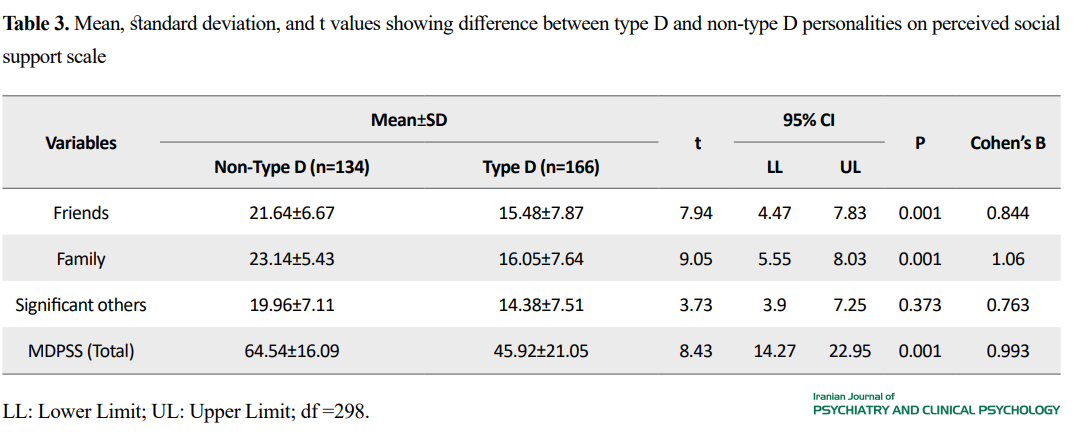

The t-test was also carried out to examine the difference between Type D and non-Type D individuals on perceived social support (Table 3).

To test the mediating effects of PSS on the relationship between distressed personality and psychosomatic symptoms, we performed the mediating analysis. Regression analysis showed that distressed personality significantly predict psychosomatic symptoms (β = -0.065, t298 = - 8.46, P< 0.001) and the mediator significantly predicted PSS (β = 1.083, t298= -12.16, P<0.001). The analysis results demonstrated the mediating effects of PSS in the relationship between distressed personality and psychosomatic symptoms. A further mediation analysis was conducted using depression as a dependent variable. Regression analysis showed that type D personality significantly predicted depression (β = -0.095, t298 = -6.498, P<0.001). Mediation analysis showed that PSS mediated the relationship between distressed personality and depression.

According to Table 2, significant t differences on psychosomatic (t= 11.15, P>0.001), perceived social support (t = -23.88, P>0.001), depression (t= 9.26, P>0.001), anxiety (t= 13.33, P>0.001) was found between type D and non-Type D individuals.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The current study‘s findings show that Type D personality has a relationship with depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic symptoms (Table 2). The observed relationship of Type D personality with depression is consistent with other studies. Doyle, McGee, Delaney, Motterlini, and Conroy [5], based on a longitudinal study, concluded that Type D is a probable cause of depression. Van Dooren et al. [22] reported a high-risk factor of Type D personality for depression. Multivariable regression analysis of the study further suggests the association of Type D personality with depression, inflammation, and endothelial problems. Another study was conducted to investigate the independent relationship of Type D personality with social and generalized anxiety in a large general population (N= 2475). The study results indicate that Type D individuals manifest both social and generalized anxiety [23]. Tasdelen and Yage [24] investigated depression, Type D personality, somatosensory amplification level, childhood trauma in panic disorder patients. The study concluded that individuals with panic disorder also show symptoms of depression, anxiety, and Type D childhood trauma. However, no relationship has been found between panic disorder and somatic magnification. Besides, the association of depression and anxiety with Type D personality and psychosomatic symptoms have also been noticed in the distressed population. The findings of the present study also show psychosomatic symptoms in the Type D individuals as compared to non-Type D. The present study results are in line with the previous studies. A longitudinal cohort observational study was conducted that a somatosensory-related disorder shows 63% prevalence of Type D personality features. Condén, Leppert, Ekselius, and Åslund [25] conducted a study and argued that adolescent with Type D personality shows more psychosomatic and musculoskeletal symptoms. In addition, our study explored the relationship between Type D personality and different kinds of Perceived Social Support (PSS) from family, friends, and significant others. Table 3 suggests that Type D individuals perceived less social support from friends, family, and significant others compared to non-Type D people. These findings indicate that distressed personality traits (NA, SI) significantly affect all dimensions of PSS. The current results are in line with the previous study conducted on the general population in Germany, which reported a negative correlation between Type D personality and social support [26]. To see the relationships between Type D personality, psychosomatic symptoms, and depression in more detail, the mediating effect of Type D personality was examined using the regression analysis. The results revealed that we should increase perceived social support in Type D individuals to minimize depression and psychosomatic symptoms. A study was conducted on the relationship between Type D personality, QOL, and coronary heart disease. The findings concluded that Type D personality might affect health-related QOL in coronary heart disease. The study also reported the mediating role of depression, anxiety, and social support [27].

Based on the present study results and supporting evidence from previous studies, we can safely assume that Type D personality traits may be the key factor of developing not only depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic disorders but also different chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and heart-related problems. Type D personality may also create management problems of these medical diseases. For example, Spek et al. [28] reported that Type D individuals have to face difficulties in coping and managing stress in diabetes. Therefore, effective therapeutic intervention to improve perceived social support may lower depression, psychosomatic symptoms, and other medical illnesses associated with Type D individuals.

Altogether, this study found that a person with Type D personality shows more anxiety, depression, and psychosomatic symptoms. The study also concluded that Type D individuals perceived less social support from family, friends, and significant others than non-Type D individuals.

In the present study, the authors used a homogenous and small-size sample. In future studies, it is recommended that results be inferred from heterogeneous and large-size samples. It is also recommended to make psychiatric diagnoses and personality assessments among the student population to get better conclusions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Both authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Refrences:

Type D personality is characterized by high scores in two areas: tending to encounter increasingly negative feelings (negative affectivity) and social inhibition of the feelings. Negative affectivity makes a person experience adverse feelings, for example, depressed mood, anxiety, outrage, and hostile feelings [1]. Conversely, emotional inhibition is characterized by maintaining a strategic distance from potential dangers ensuring social collaborations, for example, objection or absence of recompensating by others [2]. Type D personality is commonly known as a risk factor for challenging health consequences, wellbeing related to the quality of life (QOL), different types of distresses such as grief, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress [3]. Previous studies have proposed that type D personality may anticipate the onset [4] and persistence of depressive symptoms in patients with coronary illnesses [5]. Besides, the relationship between depressive symptoms and type D personality in the diabetic community and general population has also been noticed [6, 7]. A study using regression analysis on patients with heart failure demonstrated that type D personality predicts the mental and physical status of the patients [8]. Somatic Symptoms and Related Disorder (SSRD) is a person‘s tendency to understand and manifest psychological distress in physical form and to seek medical help to cure these symptoms [9]. Pain, panting, numbness, gastric issues have no clinical reasons to address. After doing a complete medical examination, one-third of symptoms remain medically unexplained [10]. A study was conducted in Iran to determine the relationship between somatic signs, mental health, and personality characteristics. The study showed a significant connection of somatic symptoms with mental health and personality characteristics [11]. A longitudinal study conducted in the Netherlands reported that individuals with somatic symptoms and related disorders with Type D personality got high scores on depression and anxiety [12]. Vogel found out the negative affectivity, Type D personality, and QOL had relationships with poor outcomes of total knee arthroplasty [13].

Social support is defined as behavioral support received from others, which served as a safeguard for many psychiatric illnesses/problems [14, 15]. There are three types of social support: 1) objective, 2) subjective, 3) utilization support. Objective support is known as available support; subjective support is defined as perceived support, which refers to contentment and satisfaction of support received from others. Support utilization is also known as enacted support, the term defined as any kind of support, e.g., emotional, physical, and informational support present [16]. Polman, Borkoles, and Nicholls [17] suggested no significant defensive role of perceived social support on psychological distress and Type D personality. While William and Wingate [18] reported a partial mediating role of social support with perceived stress and Type D personality. Another study on Type D personality may lead to low self-efficacy and social support in Type 2 diabetes mellitus in China [14].

In Pakistan, the concept of distressed personality is neither much known nor has been intensively investigated. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore the relationships between distressed personality, depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms. The study also intended to explore the mediating role of perceived social support with Type D, psychosomatic symptoms, and depressive symptoms.

2. Methods

Three hundred participants aged 18 to 40 years (Mean±SD: 22.25±2.66 years) were included in the study from different departments of Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women University and University of Peshawar. Both men (n=150) and women (n=150) equally participated in the study from March to September 2017. Personal information included age, sex, education, marital status, history of physical illness, and previous psychiatric illness. To measure distressed personality, we used a self-administered questionnaire comprising two subscales of Negative Affectivity (NA) and Social Inhibition (SI) [3]. Both subscales have 7 items scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The total score on each subscale ranges from 0 to 28, where higher scores indicate higher NA/SI. The Cronbach α reliability of the scale in the present study was calculated as 0.80. To measure depression and anxiety symptoms, we used an indigenous scale developed by Mumford et al. [19]. This scale has two subscales of depression and anxiety, each with 15 items. The α reliability values of the depression and anxiety scales in the present study were 0.80 and 0.80, respectively. The psychosomatic symptoms scale consists of 5-item self-report questions. They were scored on a 5-point Likert scale that measures headache, stomach ache, feeling of nervousness, feeling of irritation, and sleep problems. The scale shows good α reliability on the present sample as 0.87 [20]. Zimet, Powell, Farley, Werkman, and Berkoff [21] developed a multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS). A self-report questionnaire consists of 12 items with three subscales that assess support awareness from friends, family, and significant others. Each subscale has 4 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 84, with a high score indicates higher PSSS. In the present study, the Cronbach α was estimated as 0.94.

In this descriptive study, we contacted the head of different departments of Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Women University and University of Peshawar (Pakistan) to explain the nature and purpose of the study. To observe ethical concerns, we assured the respondent of their anonymity and the use of the data for academic purposes only. The study participants were volunteers and have the right to withdraw from the study at any stage. The questionnaire booklet comprised the demographic information sheet, Pakistan anxiety and depression scale, psychosomatic symptoms scale, PSSS, and DS14. They were successfully administered to all participants after taking their informed consent. Based on cut-off scores obtained on DS 14, two groups were formed: Type D (n= 166) and non-Type D (n= 134) individuals. In the present study, a random cluster sampling technique was used.

3. Results

A total of 300 samples participated in the study. Among these people, 71% were 18 to 23 years old; 5% were married; 85% belonged to middle socioeconomic status, and 71% were graduate students. All variables of interest show a significant correlation at 0.01 level (Table 1).

To test the study hypothesis, we performed the independent samples t-test. The results show that type D and non-Type D personalities were significantly different regarding depression, anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, and distress scale (Table 2).

To test the study hypothesis, we performed the independent samples t-test. The results show that type D and non-Type D personalities were significantly different regarding depression, anxiety, psychosomatic symptoms, and distress scale (Table 2).

The t-test was also carried out to examine the difference between Type D and non-Type D individuals on perceived social support (Table 3).

To test the mediating effects of PSS on the relationship between distressed personality and psychosomatic symptoms, we performed the mediating analysis. Regression analysis showed that distressed personality significantly predict psychosomatic symptoms (β = -0.065, t298 = - 8.46, P< 0.001) and the mediator significantly predicted PSS (β = 1.083, t298= -12.16, P<0.001). The analysis results demonstrated the mediating effects of PSS in the relationship between distressed personality and psychosomatic symptoms. A further mediation analysis was conducted using depression as a dependent variable. Regression analysis showed that type D personality significantly predicted depression (β = -0.095, t298 = -6.498, P<0.001). Mediation analysis showed that PSS mediated the relationship between distressed personality and depression.

According to Table 2, significant t differences on psychosomatic (t= 11.15, P>0.001), perceived social support (t = -23.88, P>0.001), depression (t= 9.26, P>0.001), anxiety (t= 13.33, P>0.001) was found between type D and non-Type D individuals.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The current study‘s findings show that Type D personality has a relationship with depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic symptoms (Table 2). The observed relationship of Type D personality with depression is consistent with other studies. Doyle, McGee, Delaney, Motterlini, and Conroy [5], based on a longitudinal study, concluded that Type D is a probable cause of depression. Van Dooren et al. [22] reported a high-risk factor of Type D personality for depression. Multivariable regression analysis of the study further suggests the association of Type D personality with depression, inflammation, and endothelial problems. Another study was conducted to investigate the independent relationship of Type D personality with social and generalized anxiety in a large general population (N= 2475). The study results indicate that Type D individuals manifest both social and generalized anxiety [23]. Tasdelen and Yage [24] investigated depression, Type D personality, somatosensory amplification level, childhood trauma in panic disorder patients. The study concluded that individuals with panic disorder also show symptoms of depression, anxiety, and Type D childhood trauma. However, no relationship has been found between panic disorder and somatic magnification. Besides, the association of depression and anxiety with Type D personality and psychosomatic symptoms have also been noticed in the distressed population. The findings of the present study also show psychosomatic symptoms in the Type D individuals as compared to non-Type D. The present study results are in line with the previous studies. A longitudinal cohort observational study was conducted that a somatosensory-related disorder shows 63% prevalence of Type D personality features. Condén, Leppert, Ekselius, and Åslund [25] conducted a study and argued that adolescent with Type D personality shows more psychosomatic and musculoskeletal symptoms. In addition, our study explored the relationship between Type D personality and different kinds of Perceived Social Support (PSS) from family, friends, and significant others. Table 3 suggests that Type D individuals perceived less social support from friends, family, and significant others compared to non-Type D people. These findings indicate that distressed personality traits (NA, SI) significantly affect all dimensions of PSS. The current results are in line with the previous study conducted on the general population in Germany, which reported a negative correlation between Type D personality and social support [26]. To see the relationships between Type D personality, psychosomatic symptoms, and depression in more detail, the mediating effect of Type D personality was examined using the regression analysis. The results revealed that we should increase perceived social support in Type D individuals to minimize depression and psychosomatic symptoms. A study was conducted on the relationship between Type D personality, QOL, and coronary heart disease. The findings concluded that Type D personality might affect health-related QOL in coronary heart disease. The study also reported the mediating role of depression, anxiety, and social support [27].

Based on the present study results and supporting evidence from previous studies, we can safely assume that Type D personality traits may be the key factor of developing not only depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic disorders but also different chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and heart-related problems. Type D personality may also create management problems of these medical diseases. For example, Spek et al. [28] reported that Type D individuals have to face difficulties in coping and managing stress in diabetes. Therefore, effective therapeutic intervention to improve perceived social support may lower depression, psychosomatic symptoms, and other medical illnesses associated with Type D individuals.

Altogether, this study found that a person with Type D personality shows more anxiety, depression, and psychosomatic symptoms. The study also concluded that Type D individuals perceived less social support from family, friends, and significant others than non-Type D individuals.

In the present study, the authors used a homogenous and small-size sample. In future studies, it is recommended that results be inferred from heterogeneous and large-size samples. It is also recommended to make psychiatric diagnoses and personality assessments among the student population to get better conclusions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Both authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Refrences:

- Watson D, Clark LA. Negative effectivity: the disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin. 1984; 96(3):465. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465] [PMID]

- Asendorpf JB. Social inhibition: a general-developmental perspective Seattle. Hogrefe: Huber Publishers. 1993. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-97654-004

- Denollet J. DS14: Standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005; 67(1):89-97. [DOI:10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49] [PMID]

- Pedersen SS, Ong AT, Sonnenschein K, Serruys PW, Erdman RA, van Domburg RT. Type D personality and diabetes predict the onset of depressive symptoms in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. American Heart Journal. 2006; 151(2):367-e1. [DOI:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.012] [PMID]

- Doyle F, McGee H, Delaney M, Motterlini N, Conroy R. Depressive vulnerabilities predict depression status and trajectories of depression over 1 year in persons with acute coronary syndrome. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2011; 33(3):224-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.03.008] [PMID]

- Michal M, Wiltink J, Grande G, Beutel ME, Brähler E. Type D personality is independently associated with major psychosocial stressors and increased health care utilization in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011; 134(1-3):396-403. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.033] [PMID]

- Nefs G, Speight J, Pouwer F, Pop V, Bot M, Denollet J. Type D personality, suboptimal health behaviors and emotional distress in adults with diabetes: Results from Diabetes MILES-The Netherlands. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2015; 108(1):94-105. [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.015] [PMID]

- Schiffer AA, Pedersen SS, Broers H, Widdershoven JW, Denollet J. Type-D personality but not depression predicts severity of anxiety in heart failure patients at 1-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008; 106(1-2):73-81. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.021] [PMID]

- van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Balkom AJ. The concept of comorbidity in somatoform disorder-a DSM-V alternative for the DSM-IV classification of somatoform disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010; 68(1):95-100. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.011] [PMID]

- Perez DL, Barsky AJ, Vago DR, Baslet G, Silbersweig DA. A neural circuit framework for somatosensory amplification in somatoform disorders. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2015; 27(1):e40-50. [DOI:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13070170] [PMID]

- Mostafaei S, Kabir K, Kazemnejad A, Feizi A, Mansourian M, Keshteli AH, et al. Explanation of somatic symptoms by mental health and personality traits: Application of Bayesian regularized quantile regression in a large population study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019; 19(1):207. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-019-2189-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- De Vroege L, de Heer E, van der Thiel E, van den Broek K, Van Eck Van Der Sluijs J, van der Feltz- Cornelis C. Type D personality, concomitant depressive and anxiety disorders, and treatment outcome in Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders: An observational longitudinal cohort study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019; 10:417. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00417] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vogel M, Riediger C, Krippl M, Frommer J, Lohmann C, Illiger S. Negative affect, type D personality, quality of life, and dysfunctional outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. Pain Research and Management. 2019; 2019. [DOI:10.1155/2019/6393101] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shao Y, Yin H, Wan C. Type D personality as a predictor of self-efficacy and social support in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2017; 13:855. [DOI:10.2147/NDT.S128432] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gomes-Villas Boas LC, Foss MC, Freitas MC, Pace AE. Relação entre apoio social, adesão aos tratamentos e controle metabólico de pessoas com diabetes mellitus. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2012; 20(1):52-8. [DOI:10.1590/S0104-11692012000100008] [PMID]

- Siedlecki KL, Salthouse TA, Oishi S, Jeswani S. The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research. 2014; 117(2):561-76. [DOI:10.1007/s11205-013-0361-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Polman R, Borkoles E, Nicholls AR. Type D personality, stress, and symptoms of burnout: The influence of avoidance coping and social support. British Journal of Health Psychology. 15(3):681-96. [DOI:10.1348/135910709X479069] [PMID]

- Williams L, Wingate A. Type D personality, physical symptoms and subjective stress: The mediating effects of coping and social support. Psychology & Health. 2012; 27(9):1075-85. [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2012.667098] [PMID]

- Mumford DB, Ayub M, Karim R, Izhar N, Asif A, Bavington JT. Development and validation of a questionnaire for anxiety and depression in Pakistan. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005; 88(2):175-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.015] [PMID]

- Åslund C, Starrin B, Nilsson KW. Social capital in relation to depression, musculoskeletal pain, and psychosomatic symptoms: a cross-sectional study of a large population-based cohort of Swedish adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10(1):715. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-10-715] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988; 52(1):30-41. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2]

- van Dooren FE, Denollet J, Verhey FR, Stehouwer CD, Sep SJ, Henry RM, et al. Psychological and personality factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus, presenting the rationale and exploratory results from The Maastricht Study, a population-based cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016; 16(1):17. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-016-0722-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kupper N, Denollet J. Type D personality is associated with social anxiety in the general population. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014; 21(3):496-505. [DOI:10.1007/s12529-013-9350-x] [PMID]

- Taşdelen Y, Yağcı İ. Anxiety, depression, type D personality, somatosensory amplification levels and childhood traumas in patients with panic disorders. Journal of Surgery and Medicine. 2019; 3(5):366-70. [DOI:10.28982/josam.518289]

- Condén E, Leppert J, Ekselius L, Åslund C. Type D personality is a risk factor for psychosomatic symptoms and musculoskeletal pain among adolescents: A cross-sectional study of a large population-based cohort of Swedish adolescents. BMC Pediatrics. 2013; 13(1):11. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2431-13-11] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Grande G, Romppel M, Michal M, Brähler E. The type D construct. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2014; 30(4):283-288. [DOI:10.1027/1015-5759/a000189]

- Staniute M, Brozaitiene J, Burkauskas J, Kazukauskiene N, Mickuviene N, Bunevicius R. Type D personality, mental distress, social support and health-related quality of life in coronary artery disease patients with heart failure: A longitudinal observational study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015; 13(1):1. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-014-0204-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Spek V, Nefs G, Mommersteeg PM, Speight J, Pouwer F, Denollet J. Type D personality and social relations in adults with diabetes: Results from diabetes MILES-The Netherlands. Psychology & Health. 2018; 33(12):1456-71. [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2018.1508684] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2020/06/27 | Accepted: 2020/11/7 | Published: 2021/04/20

Received: 2020/06/27 | Accepted: 2020/11/7 | Published: 2021/04/20

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |