Mon, Dec 15, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 27, Issue 1 (Spring 2021)

IJPCP 2021, 27(1): 16-31 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yaghoubi S, Birashk B, Aghebati A, Ashouri A. Mediating Role of External Shame and Self-compassion in the Relationship Between Peer Victimization and Depression in Adolescents. IJPCP 2021; 27 (1) :16-31

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3150-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3150-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,birashk.b@iums.ac.ir

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 7102 kb]

(2638 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5815 Views)

Full-Text: (3783 Views)

1. Introduction

Peer victimization is the experience among children of being a target of the aggressive behavior of other children. Peer victimization is prevalent and can lead to mental health difficulties [4]. Among the outcomes of peer victimization, depression has been reported more; however, not all adolescents who experience victimization develop depression. Thus, identifying the mechanisms through which peer victimization is related to depression is important for development of interventions to reduce the negative impacts of peer victimization. Two potential mechanisms are external shame and self-compassion. External shame refers to how one perceives oneself as unattractive to others and, therefore, has a feelings of being rejected and vulnerable to attacks from others. It has a strong association with depression [19, 20]. Since adolescents are more sensitive to the images they create in others and being victimized by peers is an experience that involves humiliation, this phenomenon can make adolescents vulnerable to external shame and expose them to depression. However, studies have shown that shame has a mediating role which suggests that there are other psychological mechanisms. Another potential mechanism is self-compassion. A self-compassionate person has a realistic awareness of his/her strengths and weaknesses, sees them as part of the common experience in human beings and takes a balanced perspective on them [26, 27]. Peer victimization is associated with emotion dysregulation [32]. Thus, the development of self-compassion as an effective emotion regulation strategy can be impaired in victims. To our knowledge, no study on the role of self-compassion in the context of peer victimization has been conducted so far.

The mediating role of external shame and self-compassion can be well justified based on the compassionate mind theory of Gilbert. According to theory, humans are born with an innate desire to belong to a group and create positive emotions in others. Experiencing hostile environment can activate the threat system in which humans use safety strategies to protect themselves but these strategies may have unintended consequences such as rumination, feeling of unworthiness and depression. What sustain this cycle going is shame, self-attack and reduced self-compassion [40, 41]. Based on this approach, the present study aims to examine the mediating role of external shame and self-compassion in the relationship between peer victimization and depression.

2. Methods

This is a descriptive correlational study. The study population consists of all middle-school students in Shahin Shahr city, Isfahan, Iran during 2018-2019. Samples were selected using a multi-stage cluster sampling method. The sample size was determined 300 considering a sample drop and given that there is need for at least 20 cases for each parameter [43]. To collect the data, Multidimensional Peer-Victimization Scale, Other As Shamer Scale, Self-Compassionate Scale-Short Form, and Mood & Feeling Questionnaire were used [44, 46, 48, 50]. The data were analyzed in SPSS V. 19 and AMOS V. 20 applications.

3. Results

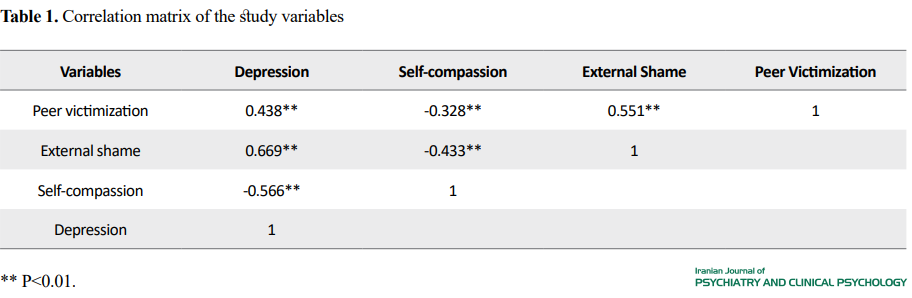

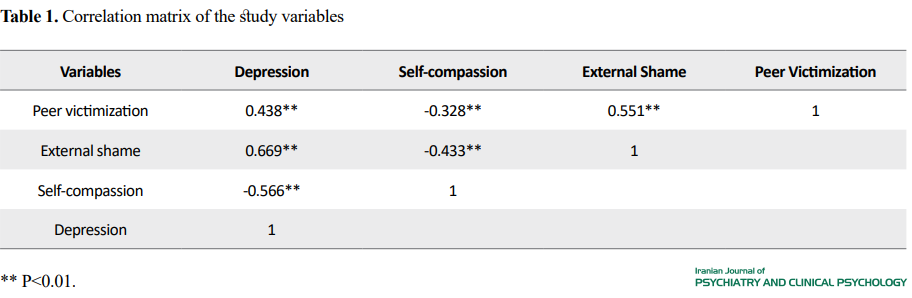

Pearson’s correlation test results showed a significant correlation (Table 1).

The results of path analysis showed that the direct paths between the study variables were significant except between peer victimization and depression; therefore, the path between them was removed (Figure 1).

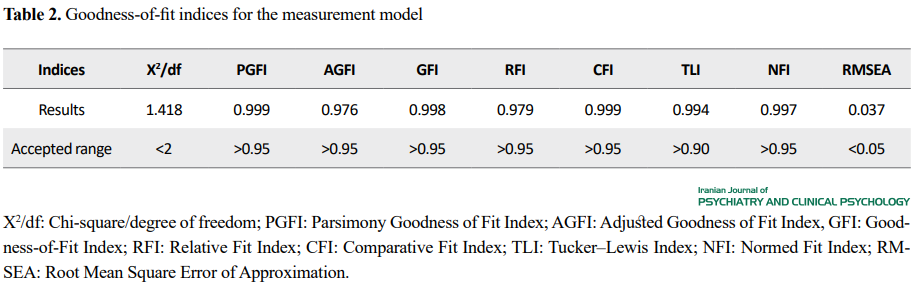

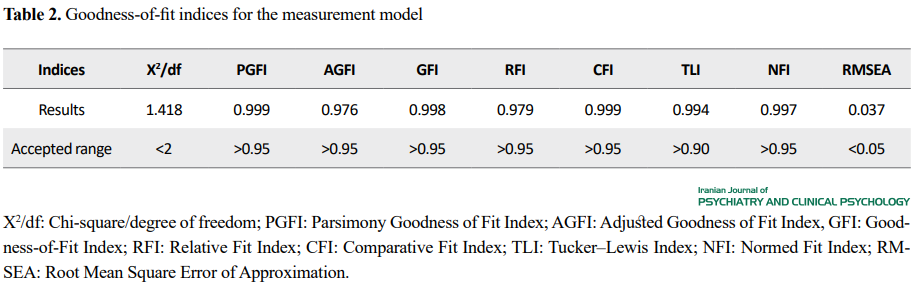

The evaluation of measurement model by using fit indices demonstrated that the measurement model had a good fitness (Table 2).

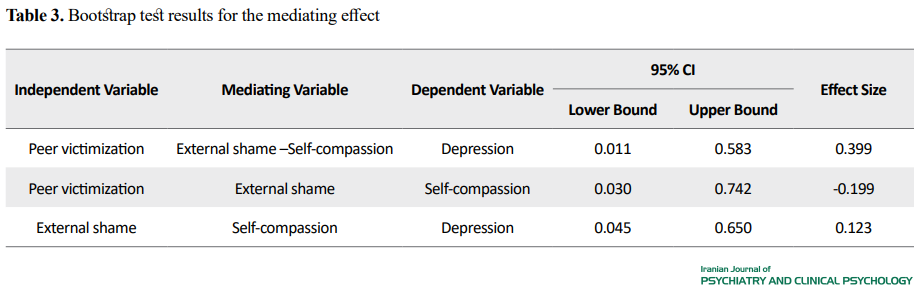

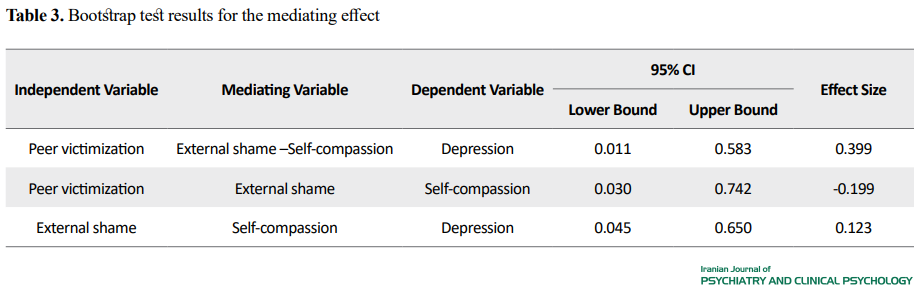

To evaluate the mediating effect, the Bootstrap test was used. The results showed that all of the three indirect paths were significant (Table 3).

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the mediating roles of external shame and self-compassion in the relationship between peer victimization and depression. Findings showed that the study model had a good fitness. That is, students experiencing higher levels of peer victimization reported higher levels of external shame, which was associated with lower levels of self-compassion and depression. The results are consistent with the results of Irwin et al. Strom et al. Duarte et al. Jativa and Cerezo, and Zhang et al. [23, 24,25, 35, 37]. Due to the increase in the sense of belonging and metacognitive abilities in adolescence and given that youth feel humiliated by peer victimization, the victim may think that others have a negative perceptions of him/her. According to Gilbert, victimization by peers may create a hostile environment, stimulate the threat system and activate the fear of getting hurt by others [40]. External shame is associated with the secretion of cortisol (a steroid hormone related to the threat system) and accompanied with adopting coping strategies (avoidance, refusing to ask for help) which intensify depression. The victims may learn self-attack from a bully and lead to lack of self-compassion in them. People with low self-compassion are more likely to engage in self-criticism [20] and judge their negative aspects which may be the same aspects targeted in peer victimization. Research has shown that self-criticism is one of important causes of depression, even years after becoming a victim.

These results of this study may help explain why peer victimization does not put anyone in a vulnerable position. In fact, peer victimization is associated with depressive symptoms, through believing in the negative judgment of others and consequently, through a kind and balanced attitude towards one’s shortcomings and weaknesses. The importance of interventions that emphasize on reducing shame and increasing self-compassion in coping with peer victimization and treating depression can be the potential clinical implications of the results of this study.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR. IUMS. REC.1398.099). According to research ethics, a written consent must be obtained from the parents, if the subjects are children (under 18 years of age). Also, one of the exclding criteria was the withdrawal of the participant from continuing the research. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Methodology: Soheila Yaghoubi and Ahmad Ashouri; Date analysis: Soheila Yaghoubi and Ahmad Ashouri; Research: Asma Aqebati and Soheila Yaghoubi; writing – original draft: Behrouz Birshak and Soheila Yaghoubi; Writing – review & editing: Asma Aqebati and Soheila Yaghoubi; Resources: Soheila Yaghoubi and Asma Aqbati; Supervision and coordination: Behrooz Birshak.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Education Organization of Isfahan and all participants for their cooperation.

Refrences:

Peer victimization is the experience among children of being a target of the aggressive behavior of other children. Peer victimization is prevalent and can lead to mental health difficulties [4]. Among the outcomes of peer victimization, depression has been reported more; however, not all adolescents who experience victimization develop depression. Thus, identifying the mechanisms through which peer victimization is related to depression is important for development of interventions to reduce the negative impacts of peer victimization. Two potential mechanisms are external shame and self-compassion. External shame refers to how one perceives oneself as unattractive to others and, therefore, has a feelings of being rejected and vulnerable to attacks from others. It has a strong association with depression [19, 20]. Since adolescents are more sensitive to the images they create in others and being victimized by peers is an experience that involves humiliation, this phenomenon can make adolescents vulnerable to external shame and expose them to depression. However, studies have shown that shame has a mediating role which suggests that there are other psychological mechanisms. Another potential mechanism is self-compassion. A self-compassionate person has a realistic awareness of his/her strengths and weaknesses, sees them as part of the common experience in human beings and takes a balanced perspective on them [26, 27]. Peer victimization is associated with emotion dysregulation [32]. Thus, the development of self-compassion as an effective emotion regulation strategy can be impaired in victims. To our knowledge, no study on the role of self-compassion in the context of peer victimization has been conducted so far.

The mediating role of external shame and self-compassion can be well justified based on the compassionate mind theory of Gilbert. According to theory, humans are born with an innate desire to belong to a group and create positive emotions in others. Experiencing hostile environment can activate the threat system in which humans use safety strategies to protect themselves but these strategies may have unintended consequences such as rumination, feeling of unworthiness and depression. What sustain this cycle going is shame, self-attack and reduced self-compassion [40, 41]. Based on this approach, the present study aims to examine the mediating role of external shame and self-compassion in the relationship between peer victimization and depression.

2. Methods

This is a descriptive correlational study. The study population consists of all middle-school students in Shahin Shahr city, Isfahan, Iran during 2018-2019. Samples were selected using a multi-stage cluster sampling method. The sample size was determined 300 considering a sample drop and given that there is need for at least 20 cases for each parameter [43]. To collect the data, Multidimensional Peer-Victimization Scale, Other As Shamer Scale, Self-Compassionate Scale-Short Form, and Mood & Feeling Questionnaire were used [44, 46, 48, 50]. The data were analyzed in SPSS V. 19 and AMOS V. 20 applications.

3. Results

Pearson’s correlation test results showed a significant correlation (Table 1).

The results of path analysis showed that the direct paths between the study variables were significant except between peer victimization and depression; therefore, the path between them was removed (Figure 1).

The evaluation of measurement model by using fit indices demonstrated that the measurement model had a good fitness (Table 2).

To evaluate the mediating effect, the Bootstrap test was used. The results showed that all of the three indirect paths were significant (Table 3).

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the mediating roles of external shame and self-compassion in the relationship between peer victimization and depression. Findings showed that the study model had a good fitness. That is, students experiencing higher levels of peer victimization reported higher levels of external shame, which was associated with lower levels of self-compassion and depression. The results are consistent with the results of Irwin et al. Strom et al. Duarte et al. Jativa and Cerezo, and Zhang et al. [23, 24,25, 35, 37]. Due to the increase in the sense of belonging and metacognitive abilities in adolescence and given that youth feel humiliated by peer victimization, the victim may think that others have a negative perceptions of him/her. According to Gilbert, victimization by peers may create a hostile environment, stimulate the threat system and activate the fear of getting hurt by others [40]. External shame is associated with the secretion of cortisol (a steroid hormone related to the threat system) and accompanied with adopting coping strategies (avoidance, refusing to ask for help) which intensify depression. The victims may learn self-attack from a bully and lead to lack of self-compassion in them. People with low self-compassion are more likely to engage in self-criticism [20] and judge their negative aspects which may be the same aspects targeted in peer victimization. Research has shown that self-criticism is one of important causes of depression, even years after becoming a victim.

These results of this study may help explain why peer victimization does not put anyone in a vulnerable position. In fact, peer victimization is associated with depressive symptoms, through believing in the negative judgment of others and consequently, through a kind and balanced attitude towards one’s shortcomings and weaknesses. The importance of interventions that emphasize on reducing shame and increasing self-compassion in coping with peer victimization and treating depression can be the potential clinical implications of the results of this study.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR. IUMS. REC.1398.099). According to research ethics, a written consent must be obtained from the parents, if the subjects are children (under 18 years of age). Also, one of the exclding criteria was the withdrawal of the participant from continuing the research. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Methodology: Soheila Yaghoubi and Ahmad Ashouri; Date analysis: Soheila Yaghoubi and Ahmad Ashouri; Research: Asma Aqebati and Soheila Yaghoubi; writing – original draft: Behrouz Birshak and Soheila Yaghoubi; Writing – review & editing: Asma Aqebati and Soheila Yaghoubi; Resources: Soheila Yaghoubi and Asma Aqbati; Supervision and coordination: Behrooz Birshak.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Education Organization of Isfahan and all participants for their cooperation.

Refrences:

- Galambos NL, Leadbeater BJ, Barker ET. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004; 28(1):16-25. [DOI:10.1080/01650250344000235]

- Swearer SM, Hymel S. Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. American Psychologist. 2015; 70(4):344. [DOI:10.1037/a0038929] [PMID]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Hamby S. Let’s prevent peer victimization, not just bullying. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012; 36(4):271–4. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.12.001] [PMID]

- Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000; 41(4):441-55. [DOI:10.1111/1469-7610.00629] [PMID]

- Troop-Gordon W. Peer victimization in adolescence: The nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. Journal of Adolescence. 2017; 55:116-28. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.012] [PMID]

- Mazaheri Tehrani MA, Shiri S, Valipour M. [Studying nature and prevalence of bullying in zanjan’s rural secondary schools (Persian)]. Educational Psychology. 2015; 11(36):17-38. https://jep.atu.ac.ir/article_1588_en.html

- Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Graham S. Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say?. Child Development. 2007; 78(6):1706-22.[DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01097.x] [PMID]

- Copeland WE, Wolke D, Angold A, Costello EJ. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013; 70(4):419-26.[DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bowes L, Joinson C, Wolke D, Lewis G. Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. The BMJ. 2015; 350. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.h2469] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cairns KE, Yap MB, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. Identifying prevention strategies for adolescents to reduce their risk of depression: A Delphi consensus study. Journal of affective disorders. 2015; 183:229-38.[DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.019] [PMID]

- Brendgen M, Poulin F, Denault AS. Peer victimization in school and mental and physical health problems in young adulthood: Examining the role of revictimization at the workplace. Developmental Psychology. 2019; 55(10):2219-30. [DOI:10.1037/dev0000771] [PMID]

- Lotfi S, Dolatshahi B, Mohammadkhani P, Campbell M, Dogaheh ER. [Prevalence of bullying and its relationship with trauma symptoms in young Iranian students (Persian)]. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology. 2014; 2(4):271-6. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/83700/

- Ebrahimi A, Hakim Shoshtari M, Asgharzade A, Karsazi H. [Depression-anxiety symptoms and its relatinship with childhood teasing experiences (Persian)]. Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology. 2017; 12(45):27-37. https://jtbcp.riau.ac.ir/article_1151_82443d3740e2e179dd3df6bfd905df10.pdf

- Alba J, Calvete E, Wante L, Van Beveren ML, Braet C. Early maladaptive schemas as moderators of the association between bullying victimization and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2018; 42(1):24-35. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-017-9874-5]

- Baker OE, Bugay A. Peer victimization and depressive symptoms: The mediation role of loneliness. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011; 30:1303-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.253]

- Du C, DeGuisto K, Albright J, Alrehaili SJIJoPS. Peer support as a mediator between bullying victimization and depression. International Journal of Psychological Studies. 2018; 10(1):59. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v10n1p59]

- Chu XW, Fan CY, Liu QQ, Zhou ZK. Cyberbullying victimization and symptoms of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: Examining hopelessness as a mediator and self-compassion as a moderator. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018; 86:377-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.039]

- Zhou ZK, Liu QQ, Niu GF, Sun XJ, Fan CY. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: A moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017; 104:137-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.040]

- Gilbert P. The evolution of shame as marker for relationship security. In: Tracy J, Robins RW, Tangney JP, editors. The Self-Conscious Emotions Theory and Research. New York: Guilford; 2007.

- Gilbert P, Irons C. Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. In: Sheeber LB, Allen NB, editors. Adolescent Emotional Development and the Emergence of Depressive Disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511551963.011]

- Kim S, Thibodeau R, Jorgensen RS. Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2011; 137(1):68. [DOI:10.1037/a0021466] [PMID]

- Menesini E, Camodeca M. Shame and guilt as behaviour regulators: Relationships with bullying, victimization and prosocial behaviour. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008; 26(2):183-96. [DOI:10.1348/026151007X205281]

- Irwin A, Li J, Craig W, Hollenstein T. The role of shame in the relation between peer victimization and mental health outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019; 34(1):156-81.[DOI:10.1177/0886260516672937] [PMID]

- Strøm IF, Aakvaag HF, Birkeland MS, Felix E, Thoresen S. The mediating role of shame in the relationship between childhood bullying victimization and adult psychosocial adjustment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2018; 9(1):1418570. [DOI:10.1080/20008198.2017.1418570] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Rodrigues T. Being bullied and feeling ashamed: Implications for eating psychopathology and depression in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence. 2015; 44:259-68. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.005] [PMID]

- Neff K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003; 2(2):85-101. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309032]

- Yaghoubi S, Akrami N. [Role of Self-Compassion in Prediction of Forgiveness and Empathy in Young Adults (Persian)]. Positive Psychology Research. 2016; 2(3):35-48. http://ensani.ir/file/download/article/1560860673-10047-95-15.pdf

- Bluth K, Mullarkey M, Lathren C. Self-compassion: A potential path to adolescent resilience and positive exploration. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018; 27(9):3037-47.[DOI:10.1007/s10826-018-1125-1]

- MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012; 32(6):545-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003] [PMID]

- Neff KD, Vonk R. Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality. 2009; 77(1):23-50. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309027]

- Bagheri J, Birashk B, Dehghani M, Asgharnejad AA. The relationship between object relations and the severity of depression symptoms: The mediating role of self-compassion. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2019; 25(3):328-43. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.25.3.328]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Baruch DE, Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW. Factors associated with co-occurring borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users: The roles of childhood maltreatment, negative affect intensity/reactivity, and emotion dysregulation. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008; 49(6):603-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.04.005] [PMID]

- Vettese LC, Dyer CE, Li WL, Wekerle C. Does self-compassion mitigate the association between childhood maltreatment and later emotion regulation difficulties? A preliminary investigation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2011; 9(5):480-91. [DOI:10.1007/s11469-011-9340-7]

- Tanaka M, Wekerle C, Schmuck ML, Paglia-Boak A, MAP Research Team. The linkages among childhood maltreatment, adolescent mental health, and self-compassion in child welfare adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011; 35(10):887-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.003] [PMID]

- Játiva R, Cerezo MA. The mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between victimization and psychological maladjustment in a sample of adolescents. Child abuse & Neglect. 2014; 38(7):1180-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.005] [PMID]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2011; 7(1):27-56.[DOI:10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1]

- Zhang H, Carr ER, Garcia-Williams AG, Siegelman AE, Berke D, Niles-Carnes LV, Patterson B, Watson-Singleton NN, Kaslow NJ. Shame and depressive symptoms: Self-compassion and contingent self-worth as mediators? Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2018; 25(4):408-19. [DOI:10.1007/s10880-018-9548-9] [PMID]

- Barnard LK, Curry JF. The relationship of clergy burnout to self-compassion and other personality dimensions. Pastoral Psychology. 2012; 61(2):149-63. [DOI:10.1007/s11089-011-0377-0]

- Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C. Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: Implications for eating disorders. Eating Behaviors. 2013; 14(2):207-10.[DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005] [PMID]

- Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice. 2006; 13(6):353-79. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.507]

- Gilbert P. An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behavior therapy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010; 3(2):97-112. [DOI:10.1521/ijct.2010.3.2.97]

- Johnson EA, O'Brien KA. Self-compassion soothes the savage ego-threat system: Effects on negative affect, shame, rumination, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2013; 32(9):939-63. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2013.32.9.939]

- Streiner DL. Finding our way: an introduction to path analysis. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005; 50(2):115-22. [DOI:10.1177/070674370505000207] [PMID]

- Mynard H, Joseph S. Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression. 2000; 26(2):169-78. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:23.0.CO;2-A]

- Balootbangan AA, Talepasand SI. A study of factorial structure of the Persian version of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale in primary schools students in Semnan city. Koomesh. 2016; 17(3):660-8. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20163114195

- Goss K, Gilbert P, Allan S. An exploration of shame measures—I: The other as Shamer scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994; 17(5):713-7. [DOI:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90149-X]

- Foroughi A, Khanjani S, Kazemini M, Tayeri F. [Factor structure and psychometric properties of Iranian version of External Shame Scale (Persian)]. Shenakht Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015; 2(2):49-58. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=568397

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self‐Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2011; 18(3):250-5. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.702] [PMID]

- Khanjani S, Foroughi AA, Sadghi K, Bahrainian SA. [Psychometric properties of Iranian version of self-compassion scale (short form) (Persian)]. Pajoohandeh Journal. 2016; 21(5):282-9. http://pajoohande.sbmu.ac.ir/article-1-2292-en.html

- Angold A, Costello E. Mood and feelings questionnaire [MFQ]. Durham: Developmental Epidemiology Program, Duke University; 1987. [DOI:10.1037/t15197-000]

- Neshatdoust HT, Nouri N, Molari H, Kalantari M, Mehrabi HA. [Standardization of Mood and Feeling Questionnaire (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology. 2006; 9(4):334-50. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=50731

- Miles J, Shevlin M. Applying regression and correlation: A guide for students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2001.

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2001.

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008; 40(3):879-91. [DOI:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879] [PMID]

- Roth-Cline M, Nelson RM. Parental permission and child assent in research on children. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2013; 86(3):291-301. [PMCID] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2019/12/28 | Accepted: 2020/06/2 | Published: 2021/04/20

Received: 2019/12/28 | Accepted: 2020/06/2 | Published: 2021/04/20

References

1. [1] Galambos N, Leadbeater B, Barker ED. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. Int J Behav Dev. 2004;28[1]:16- 25. [DOI:10.1080/01650250344000235]

2. [2] Swearer SM, Hymel S. Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. Am Psychol. 2015;70[4]:344. [DOI:10.1037/a0038929] [PMID]

3. [3] Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Hamby S. Let's prevent peer victimization, not just bullying. Child abuse & neglect. 2012. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.12.001] [PMID]

4. [4] Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41[4]:441-55. [DOI:10.1111/1469-7610.00629] [PMID]

5. [5] Troop-Gordon W. Peer victimization in adolescence: The nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. J Adolesc. 2017; 55:116- 28. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.012] [PMID]

6. [6] Mazaheritehrani M, Shiri A, Valipoor M. Studying Nature and Prevalence of Bullying in Zanjan's Rural Secondary Schools. Edu Psy. 2015;11[36]:17-38[in persian].

7. [7] Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Graham S. Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: what does latent class analysis say? Child development. 2007;78[6]:1706-22. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01097.x] [PMID]

8. [8] Copeland WE, Wolke D, Angold A, Costello EJ. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA psychiatry. 2013;70[4]:419-26. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504] [PMID] [PMCID]

9. [9] Bowes L, Joinson C, Wolke D, Lewis G. Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 2015;350. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.h2469] [PMID] [PMCID]

10. [10] Cairns KE, Yap MB, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. Identifying prevention strategies for adolescents to reduce their risk of depression: a Delphi consensus study. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:229-38. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.019] [PMID]

11. [11] Brendgen M, Poulin F, Denault AS. Peer victimization in school and mental and physical health problems in young adulthood: Examining the role of revictimization at the workplace. Developmental psychology. 2019; 55[10]: 2219-30. [DOI:10.1037/dev0000771] [PMID]

12. [12] Lotfi S, Dolatshahi B, Mohammadkhani P, Campbell M, Rezaei Dogaheh E. Prevalence of Bullying and its Relationship with Trauma Symptoms in Young Iranian Students J Practice In Clin Psychol. 2014;2[4]:247-54[in persian]. 25

13. [13] Ebrahimi A, HakimShoshtari M, Asgharzade A, Karsazi H. Depression-Anxiety Symptoms And Its Relatinship With Childhood Teasing Experiences. Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology. 2017;12[45]:27-37[in persian].

14. [14] Alba J, Calvete E, Wante L, Van Beveren M-L, Braet C. Early Maladaptive Schemas as Moderators of the Association between Bullying Victimization and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2018;42[1]:24-35. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-017-9874-5]

15. [15] Baker OE, Bugay A. Peer Victimization and Depressive Symptoms: The Mediation Role of Loneliness. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:1303-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.253]

16. [16] Du C, DeGuisto K, Albright J, Alrehaili SJIJoPS. Peer Support as a Mediator between Bullying Victimization and Depression. 2018;10[1]:59. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v10n1p59]

17. [17] Chu X-W, Fan C-Y, Liu Q-Q, Zhou Z-KJCiHB. Cyberbullying victimization and symptoms of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: Examining hopelessness as a mediator and self-compassion as a moderator. Comput Human Behav. 2018;86:377-86 [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.039]

18. [18] Zhou Z-K, Liu Q-Q, Niu G-F, Sun X-J, Fan C-Y. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: A moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Pers Individ Dif. 2017;104:137-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.040]

19. [19] Gilbert P. The evolution of shame as marker for relationship security. In: Tracy J, Robins RW, Tangney JP, editors. The Self-Conscious Emotions Theory and Research. New York: Guilford; 2007. p. 283-309.

20. [20] Gilbert P, Irons C. Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. In: Sheeber LB, Allen NB, editors. Adolescent Emotional Development and the Emergence of Depressive Disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 195-214. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511551963.011]

21. [21] Kim S, Thibodeau R, Jorgensen RS. Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2011;137[1]:68. [DOI:10.1037/a0021466] [PMID]

22. [22] Menesini E, Camodeca M. Shame and guilt as behaviour regulators: Relationships with bullying, victimization and prosocial behaviour. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008 Jun;26(2):183-96. [DOI:10.1348/026151007X205281]

23. [23] Irwin A, Li J, Craig W, Hollenstein T. The Role of Shame in the Relation Between Peer Victimization and Mental Health Outcomes. J Interpers Violence. 2016:886260516672937. [DOI:10.1177/0886260516672937] [PMID]

24. [24] Strom IF, Aakvaag HF, Birkeland MS, Felix E, Thoresen S. The mediating role of shame in the relationship between childhood bullying victimization and adult psychosocial adjustment. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9[1]:1418570. [DOI:10.1080/20008198.2017.1418570] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. [25] Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Rodrigues T. Being bullied and feeling ashamed: Implications for eating psychopathology and depression in adolescent girls. J Adolesc. 2015;44:259-68. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.005] [PMID]

26. [26] Neff K, identity. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and identity. 2003;2[2]:85-101. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309032]

27. [27] Yaghoubi S, Akrami N. Role of Self-Compassion in Prediction of Forgiveness and Empathy in Young Adults. Positive Psychology Research. 2016; 2[3]: 35-48 [In Persian].

28. [28] Bluth K, Mullarkey M, Lathren C. Self-Compassion: A Potential Path to Adolescent Resilience and Positive Exploration. J Child Fam Stud. 2018:1-11. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-018-1125-1]

29. [29] MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32[6]:545-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003] [PMID]

30. [30] Neff KD, Vonk R. Self‐compassion versus global self‐esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. J Pers. 2009;77[1]:23-5032.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and identity. 2003;2[3]:223-50. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309027]

31. [31] Bagheri J, Birashk B, Dehghani M, Asgharnejad A. The Relationship Between Object Relations and the Severity of Depression Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion. IJPCP. 2019; 25 (3) :328-343. URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2916-fa.html [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.25.3.328]

32. [32] Gratz KL, Tull MT, Baruch DE, Bornovalova MA, Lejuez C. Factors associated with co-occurring borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users: The roles of childhood maltreatment, negative affect intensity/reactivity, and emotion dysregulation. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49[6]:603-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.04.005] [PMID]

33. [33] Vettese LC, Dyer CE, Li WL, Wekerle C. Does self-compassion mitigate the association between childhood maltreatment and later emotion regulation difficulties? A preliminary investigation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2011;9[5]:480. [DOI:10.1007/s11469-011-9340-7]

34. [34] Tanaka M, Wekerle C, Schmuck ML, Paglia-Boak A, Abuse MRTJC, Neglect. The linkages among childhood maltreatment, adolescent mental health, and self-compassion in child welfare adolescents. 2011;35[10]:887-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.003] [PMID]

35. [35] Játiva R, Cerezo MA. The mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between victimization and psychological maladjustment in a sample of adolescents. Child Abuse Negl 2014;38[7]:1180-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.005] [PMID]

36. [36] Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. J Exp Criminol. 2011;7[1]:27-56. [DOI:10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1]

37. [37] Zhang H, Carr ER, Garcia-Williams AG, Siegelman AE, Berke D, Niles-Carnes LV, et al. Shame and Depressive Symptoms: Self-compassion and Contingent Self-worth as Mediators? Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings. 2018:1-12. [DOI:10.1007/s10880-018-9548-9] [PMID]

38. [38] Barnard LK, Curry JF. The relationship of clergy burnout to self-compassion and other personality dimensions. Pastoral Psychol. 2012;61[2]:149-63. [DOI:10.1007/s11089-011-0377-0]

39. [39] Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C. Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: Implications for eating disorders. Eating behaviors. 2013 Apr 1;14[2]:207-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005] [PMID]

40. [40] Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self‐criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2006;13[6]:353-79. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.507]

41. [41] Gilbert P. An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behavior therapy. Int J Cogn Ther. 2010;3[2]:97-112. [DOI:10.1521/ijct.2010.3.2.97]

42. [42] Johnson EA, O'Brien KA. Self-compassion soothes the savage ego-threat system: Effects on negative affect, shame, rumination, and depressive symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2013;32[9]:939-63. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2013.32.9.939]

43. [43] Streiner, D L. Finding our way: an introduction to path analysis. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 2005, 50[2]: 115-122. [DOI:10.1177/070674370505000207] [PMID]

44. [44] Mynard H, Joseph S. Development of the multidimensional peer‐victimization scale. ISRA. 2000;26[2]:169-78.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:2<169::AID-AB3>3.0.CO;2-A [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:23.0.CO;2-A]

45. [45] Balootbangan AA TS. A study of factorial structure of persian version of the multidimentional peer-victimization scale in primary school students in Semnan city. komesh jr. 2016;17[3]:660-8.

46. [46] Goss K, Gilbert P, Allan S. An exploration of shame measures-I: The other as Shamer scale. Personality and Individual differences. 1994 Nov 1;17(5):713-7. [DOI:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90149-X]

47. [47] Foroughi A, khanjani s, kazemeyni M, Tayeri F. Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of Iranian Version of External Shame scale. Shenakht Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;2[2]:50-7[in persian].

48. [48] Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self‐compassion scale. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18[3]:250-5. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.702] [PMID]

49. [49] Khanjani S, Foroughi AA, Sadghi K, Bahrainian SA. Psychometric properties of Iranian version of self-compassion scale [short form]. Pajoohande. 2016;21[5]:282-9[in persian].

50. [50] Angold A, Costello E. Mood and feelings questionnaire [MFQ]. Durham: Developmental Epidemiology Program, Duke University. 1987. [DOI:10.1037/t15197-000]

51. [51] Neshatdoost HT, Noori N, molavi H, Kalantari M, mehrabi h. Standardization of Mood and Feeling Questionnaire. J Psy. 2006;9[4]:334-50[in persian].

52. [52] Miles J, Shevlin M. Applying regression and correlation: A guide for students and researchers. Sage; 2001 Mar 8.

53. [53] Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2001.

54. [54] Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior research methods. 2008 Aug 1;40(3):879-91. [DOI:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879] [PMID]

55. [55] Roth-Cline M, Nelson RM. Parental permission and child assent in research on children. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 2013 Sep;86[3]:291-301.

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |