BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2971-en.html

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

1. Introduction

Ostomy surgery is still one of the main treatments for many patients with colorectal cancers [5]. It often causes a number of physical and mental pressures, which leads to incompatibility [10]. There are few studies regarding the psychological and social consequences of depression and anxiety associated with the development of ostomy [5]. Considering the high rate of psychiatric disorders among ostomy patients in Iran, identification of the risk factors and predictors can help health care providers implement interventions to reduce these complications [16]. Regarding the association of stress with ostomy [17], the role of postoperative psychosocial support in ostomy patients [13], and the role of physical changes and dissatisfaction with physical appearance in these patients [11, 12], this study aims to seek for factors that may affect the severity of depression symptoms. To our knowledge, no study has been conducted on the predictive variables of depression in patients with ostomy.

2. Method

This is descriptive/analytical study. The study population included all ostomy patients referred to the Iranian Ostomy Association in 2018. Since in regression analyses, 15 samples for each variable can predict the variances [20] and, on the other hand, considering the probability of sample drop and return of incomplete questionnaires, 130 volunteers were selected as samples. After corresponding with the authorities of Iranian Ostomy Association, and obtaining written informed consent from participants and explaining the study objectives to them, questionnaires were distributed among them. They were taught how to answer the questions and were asked to carefully read the questions and choose the appropriate answers according to their characteristics. Each patient had 20-30 minutes to complete the questionnaire. After collecting questionnaires, there were 10 incomplete questionnaires which were excluded from the study and 120 subjects were considered as the final samples. Meanwhile, the subjects were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

The entry criteria for samples include: having permanent and temporary ostomy aged 16 years and above, not receiving counseling or psychological services for this problem, and having at least a middle school education. On the other hand, the exit criteria were: having mental (depression and taking antidepressants, epilepsy, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) and physical diseases (chronic heart disease, tuberculosis, high blood glucose, gastric ulcer, migraine and etc.) based on the patient’s medical record that can affect the patient mood, and unwillingness to participate in the study.

Patients completed The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, Perceived Stress Scale, Body Image Questionnaire, and Social Support Scale. Data were analyzed in SPSS V. 21 software by using Pearson correlation test and stepwise multiple regression analysis.

3. Results

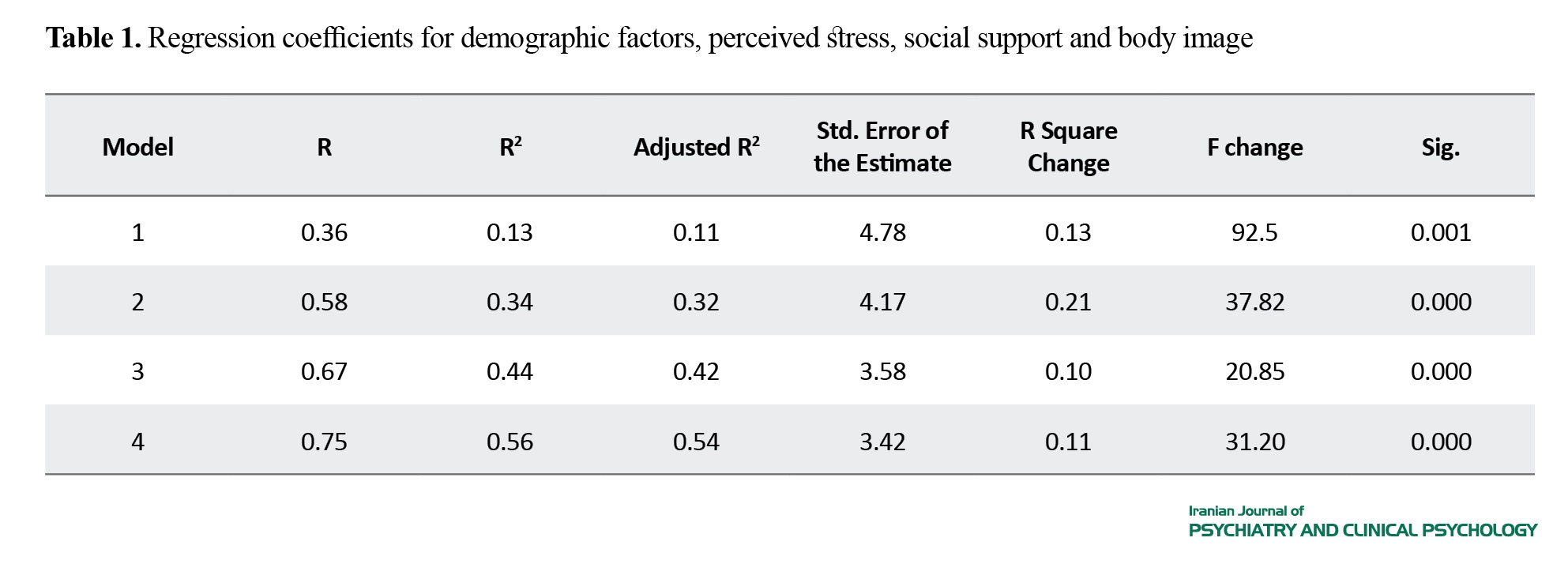

According to the results in Table 1, the F statistics shows that demographic factors, perceived stress, social support and body image can predict the severity of depressive symptoms (P<0.05). Demographic factors explained 11% of the variances in depressive symptoms. When the perceived stress was added to the model, it reached to 32%. By adding social support to the regression model, it reached to 42%. Finally, when the body image variable was entered to the regression model, the prediction power reached to 54%. Therefore, demographic factors, perceived stress, social support and body image overall can explain 54% of changes in severity of depressive symptoms. Their prediction power was 13%, 21%, 10% and 11%, respectively

4. Discussion

The results showed that perceived stress, social support and body image can predict the severity of depressive symptoms, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [30-32, 36-38, 41-44]. Psychological stress is involved in the pathology of depression and anxiety [33]. In fact, perception of stressors as uncontrollable and threatening is highly predictive of negative psychological symptoms [18]. A high level of perceived stress can lead to a decrease in self-esteem, thereby exacerbating the symptoms of depression [34]. Social support, regardless of whether a person is influenced by stress and psychological pressure or not, helps a person to avoid negative life experiences, and this has beneficial effects on health [39]. In patients who do not have social support, the risk of developing and exacerbating depressive symptoms increases with the progression of disability resulting from the disease [19]. Evidence also suggests that body image changes are associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients [45]. Most likely, body image dissatisfaction reduces self-esteem and self-sufficiency and causes a sense of inadequacy which can lead to depression [46].

Using self-report questionnaires, low number of patients and some patients’ lack of cooperation are some of the study limitations. It is suggested that further studies should be conducted using a larger sample size and other tools such as interviews and psychological tests to obtain more complete and accurate information from patients.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; they were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; moreover, they were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

Iran University of Medical Sciences financially supported this research.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, validation, review and editing: All; Authors; Research analysis, resources, data processing, writing, and drafting: Saeed Moradi; Supervision: Mohamadreza Pirmoradi.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

1.Wright J. An overview of living with a stoma. Journal of Community Nursing. 2009; 23(7):1285 ref.5. https://www.cabdirect.org/globalhealth/abstract/20103191253

2.Porrett T, McGrath A. Stoma care. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. https://books.google.com/books?id=lGq9mFhH-_IC&dq

3.Coons SJ, Chongpison Y, Wendel CS, Grant M, Krouse RS. Overall quality of life and difficulty paying for ostomy supplies in the Veterans Affairs ostomy health-related quality of life study: An exploratory analysis. Medical Care. 2007; 45(9):891-5. [DOI:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318074ce9b] [PMID]

4.Lumby J, England K. Patient satisfaction with nursing care in a colorectal surgical population. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2000; 6(3):140-5. [DOI:10.1046/j.1440-172x.2000.00194.x] [PMID]

5.Abdalla MI, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Chen W, Anton K, et al. The impact of ostomy on quality of life and functional status of Crohn’s disease patients. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2016; 22(11):2658-64. [DOI:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000930] [PMID] [PMCID]

6.Manderson L. Boundary breaches: The body, sex and sexuality after stoma surgery. Social Science & Medicine. 2005; 61(2):405-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.051] [PMID]

7.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. International Journal of Cancer. 2010; 127(12):2893-917. [DOI:10.1002/ijc.25516] [PMID]

8.Tarver T. Cancer facts & figures 2012. American Cancer Society (ACS). Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet. 2012; 16(3):366-7. [DOI:10.1080/15398285.2012.701177]

9.Rafii F, Naseh L, Parvizy S, Haghani H. Self-efficacy and the related factors in ostomates. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2011; 24(73):8-18. http://ijn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-1034-en.html

10.Upton D, Solowiej K. Pain and stress as contributors to delayed wound healing. Wound Practice & Research: Journal of the Australian Wound Management Association. 2010; 18(3):114. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=364536431309445;res=IELHEA

11.Salomé GM, de Almeida SA, Silveira MM. [Quality of life and self-esteem of patients with intestinal stoma. Journal of Coloproctology (Portuguese)]. 2014; 34(4):231-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcol.2014.05.009]

12.Geng Z, Howell D, Xu H, Yuan C. Quality of life in Chinese persons living with an ostomy. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2017; 44(3):249-56. [DOI:10.1097/WON.0000000000000323] [PMID]

13.Bavaresco DV, Schwalm MT, Jornada LK, Quadros LFA, Simon B, Ceretta LB, et al. Depressive symptoms and neurotrophin levels in ostomy patients. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria. 2018; 67(3):166-73. [DOI:10.1590/0047-2085000000203]

14.Thomas C, Madden F, Jehu D. Psychosocial morbidity in the first three months following stoma surgery. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1984; 28(3):251-7. [DOI:10.1016/0022-3999(84)90027-8]

15.Rafiei H, Hoseinabadi-Farahani MJ, Aghaei S, Hosseinzadeh K, Naseh L, Heidari M. The prevalence of psychological problems among ostomy patients: A cross-sectional study from Iran. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2017; 15(2):39-44. [DOI:10.12968/gasn.2017.15.2.39]

16.Mahjoubi B, Mohammadsadeghi H, Mohammadipour M, Mirzaei R, Moini R. Evaluation of psychiatric illness in Iranian stoma patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009; 66(3):249-53. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.10.015] [PMID]

17.Ang SGM, Chen HC, Siah RJC, He HG, Klainin-Yobas P. Stressors relating to patient psychological health following stoma surgery: An integrated literature review. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013; 40(6):587-94. [DOI:10.1188/13.ONF.587-594] [PMID]

18.Pedrelli P, Feldman GC, Vorono S, Fava M, Petersen T. Dysfunctional attitudes and perceived stress predict depressive symptoms severity following antidepressant treatment in patients with chronic depression. Psychiatry Research. 2008; 161(3):302-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.004] [PMID]

19.Ghafari SM, Shahbazian HB, Kholghi M, Haghdoust MR. [Relationship between social support and depression in diabetic patients (Persian)]. Jundishapur Scientific Medical Journal. 2010; 8(4):383-9. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=100826

20.Stevens JP. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. New York: Routledge; 2012. https://books.google.com/books?id=oIeDhzDebKwC&dq

21.Szabó M. The short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Factor structure in a young adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescence. 2010; 33(1):1-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.014] [PMID]

22.Gloster AT, Rhoades HM, Novy D, Klotsche J, Senior A, Kunik M, et al. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 in older primary care patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008; 110(3):248-59. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.023] [PMID] [PMCID]

23.Sahebi A, Asghari MJ, Salari RS. Validation of Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) for an Iranian population. Journal of Developmental Psychology (Iranian Psychologists). 2005; 1(4):299-313. http://jip.azad.ac.ir/article_512443_en.html

24.Cohen Sh, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983; 24(4):385-96. [DOI:10.2307/2136404] [PMID]

25.Razavizadeh Tabadkan BZ, Jajarmi M, Vakili Y. [The effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on ruminative thoughts, perceived stress and difficulties in emotion regulation of women with type 2 diabetes (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2019; 24(4):370-83. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.24.4.370]

26.Littleton HL, Axsom D, Pury CLS. Development of the body image concern inventory. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005; 43(2):229-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.006] [PMID]

27.Bassak Nejad S, Ghafari M. [The relationship between body dysmorphic concern and psychological problems among university students (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2007; 1(2):179-87. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=74684

28.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1991; 32(6):705-14. [DOI:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B]

29.Jahanbakhshian N, Zandipoor T. [A study on the effectiveness of group counseling based on Lazarus multimodal approach with relapsing/remitting MS patients on the improvement of mental health & social support of patients (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Studies. 2011; 7(2):65-84. [DOI:10.22051/PSY.2011.1549]

30.Beshlideh K, Zakiei A, Sahraei Z, Rajabi Gilan N, Mohammadi Askarabadi O. [The simple, multiple, and canonical relationship between alexithymia and perceived stress with general health (Persian)]. Journal of Personality & Individual Differences. 2015; 4(7):149-66. http://jpid.pgu.ac.ir/article_11214_en.html

31.Maroufizadeh S, Zareiyan A, Sigari N. Reliability and validity of Persian version of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) in adults with asthma. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2014; 17(5):361-5. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=409286

32.Wiegner L, Hange D, Björkelund C, Ahlborg Jr G. Prevalence of perceived stress and associations to symptoms of exhaustion, depression and anxiety in a working age population seeking primary care - an observational study. BMC Family Practice. 2015; 16:38. [DOI:10.1186/s12875-015-0252-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

33.de Rooij SR, Schene AH, Phillips DI, Roseboom TJ. Depression and anxiety: Associations with biological and perceived stress reactivity to a psychological stress protocol in a middle-aged population. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010; 35(6):866-77. [DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.011] [PMID]

34.Lee JS, Joo EJ, Choi KS. Perceived stress and self‐esteem mediate the effects of work‐related stress on depression. Stress & Health. 2013; 29(1):75-81. [DOI:10.1002/smi.2428] [PMID]

35.Kernis MH. Measuring self‐esteem in context: The importance of stability of self‐esteem in psychological functioning. Journal of Personality. 2005; 73(6):1569-605. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00359.x] [PMID]

36.Tajvar M, Grundy E, Fletcher A. Social support and mental health status of older people: A population-based study in Iran-Tehran. Aging & Mental Health. 2018; 22(3):344-53. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2016.1261800] [PMID]

37.Henry A, Tourbah A, Camus G, Deschamps R, Mailhan L, Castex C, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with multiple sclerosis: The mediating effects of perceived social support. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2019; 27:46-51. [DOI:10.1016/j.msard.2018.09.039] [PMID]

38.Ohara M, Nakatochi M, Okada T, Aleksic B, Nakamura Y, Shiino T, et al. Impact of perceived rearing and social support on bonding failure and depression among mothers: A longitudinal study of pregnant women. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2018; 105:71-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.09.001] [PMID]

39.Sarafino EP. Health psychology: Biopsychosocial interactions. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. https://books.google.com/books?id=nnWkQpKLOLsC&dq

40.Riahi ME, Aliverdinia A, Pourhossein SZ. Relationship between social support and mental health. Social Welfare Quarterly. 2011; 10(39):85-121. http://refahj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-322-en.html

41.Van Eck K, Morse M, Flory K. The role of body image in the link between ADHD and depression symptoms among college students. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2018; 22(5):435-45. [DOI:10.1177/1087054715580845] [PMID]

42.Aguilar Cordero MJ, Mur Villar N, Neri Sánchez M, Pimentel-Ramírez ML, García-Rillo A, Gómez Valverde E. Breast cancer and body image as a prognostic factor of depression: A case study in México City. Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2015; 31(1):371-9. [DOI:10.3305/nh.2015.31.1.7863] [PMID]

43.Silveira ML, Ertel KA, Dole N, Chasan-Taber L. The role of body image in prenatal and postpartum depression: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2015; 18(3):409-21. [DOI:10.1007/s00737-015-0525-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

44.Roomruangwong C, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Maes M. High incidence of body image dissatisfaction in pregnancy and the postnatal period: Associations with depression, anxiety, body mass index and weight gain during pregnancy. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. 2017; 13:103-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.srhc.2017.08.002] [PMID]

45.Brand-Gothelf A, Leor Sh, Apter A, Fennig S. The impact of comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders on severity of anorexia nervosa in adolescent girls. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2014; 202(10):759-62. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000194] [PMID]

46.Gjerdingen D, Fontaine P, Crow S, McGovern P, Center B, Miner M. Predictors of mothers’ postpartum body dissatisfaction. Women & Health. 2009; 49(6-7):491-504. [DOI:10.1080/03630240903423998] [PMID] [PMCID]

47.Hartley E, Hill B, McPhie S, Skouteris H. The associations between depressive and anxiety symptoms, body image, and weight in the first year postpartum: A rapid systematic review. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2018; 36(1):81-101. [DOI:10.1080/02646838.2017.1396301] [PMID]

Received: 2019/02/17 | Accepted: 2019/08/27 | Published: 2020/04/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |