Sun, Aug 31, 2025

| فارسی

Volume 24, Issue 4 (Winter 2019)

IJPCP 2019, 24(4): 426-443 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mansoori S, Mozaffar F, Noroozian M, Faizi M, Ashayeri H. Relationship Between Neuropsychological and Physical Environmental Perception in Patients With Dementia and Alzheimer Disease. IJPCP 2019; 24 (4) :426-443

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2820-en.html

URL: http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2820-en.html

1- PhD. in Architecture, Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran.

2- Associate professor in Architecture, Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran.

3- Neurology Division, Department of Psychiatry Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Professor, Architecture, Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran.

5- Professor, Neuropsychology and psychiatry, Rehabilitation of Iran University of Medical science, Tehran, Iran. ,ashayerih.neuroscientist@yahoo.com

2- Associate professor in Architecture, Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran.

3- Neurology Division, Department of Psychiatry Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Professor, Architecture, Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran.

5- Professor, Neuropsychology and psychiatry, Rehabilitation of Iran University of Medical science, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 6946 kb]

(2941 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6681 Views)

Full-Text: (5344 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

Increased longevity and aging are among the most significant risk factors of catching Alzheimer Disease (AD). Recent studies have investigated the effects of physical and neuropsychological factors on the environmental perception of with the patients with AD. However, data are scarce on the associations between the main features of the physical environment and brain activities of Ad patients [1].

2. Method

This was a descriptive analytical study, which was performed using inductive content analysis. The final outcomes were the result of the interpretation and combination of semi-structured interviews with the people with dementia AD type and their caregivers and review of the literature in this regard. In addition, the similarities and differences between the qualitative physical features of the environment were assessed from the viewpoint of the patients with AD, their caregivers, and based on the literature review. The study data were collected through semi-structured interviews (15-30 minutes) using Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Functional Assessment Staging (FAST). In total, 9 participants were enrolled in the study, including four patients with AD and five caregivers. Furthermore, the required data were extracted from the current literature. The interviews were entitled Participants with ‘AD (PAD)’ and ‘Caregiver Participants (CGP)’.

3. Results

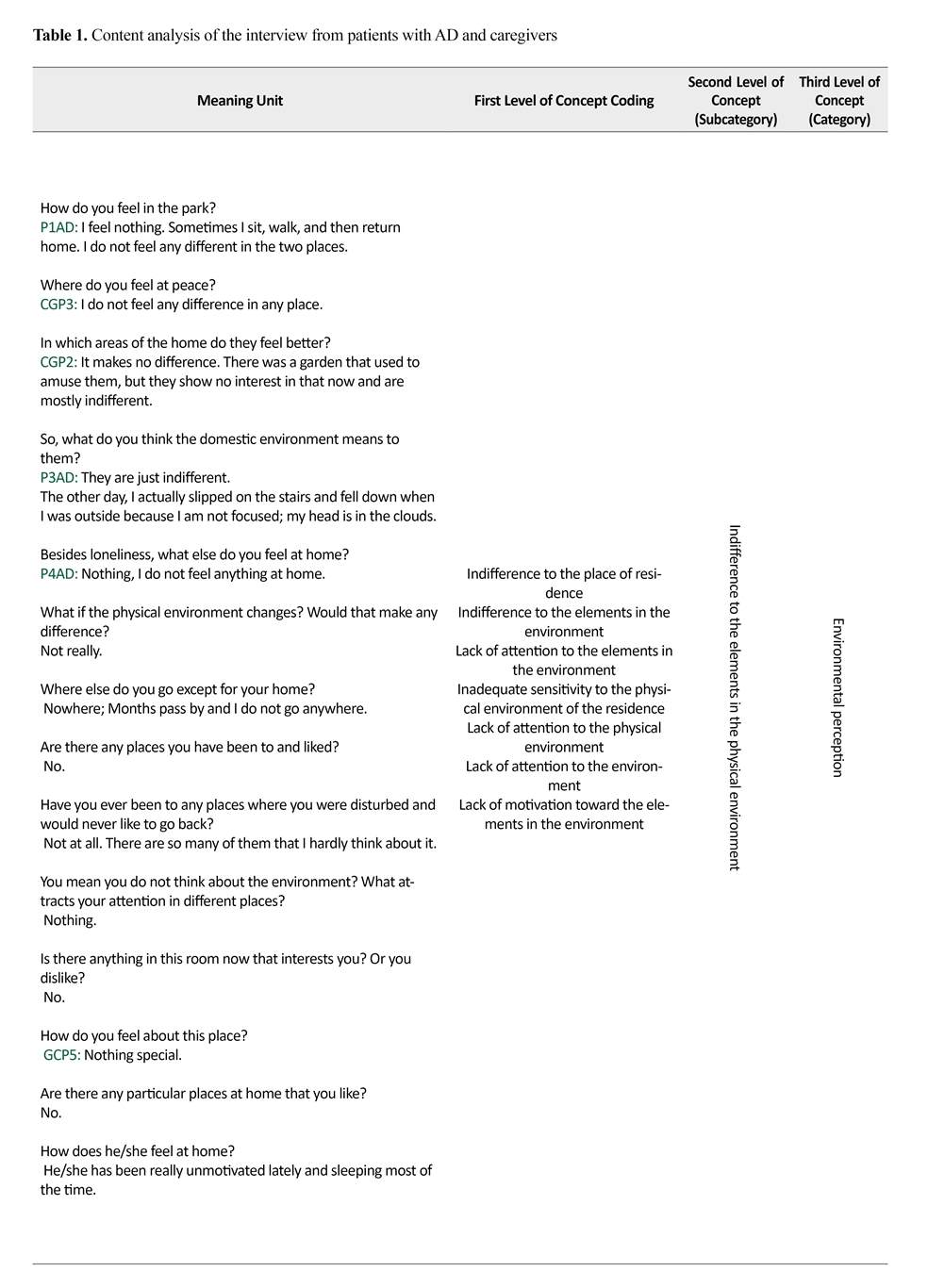

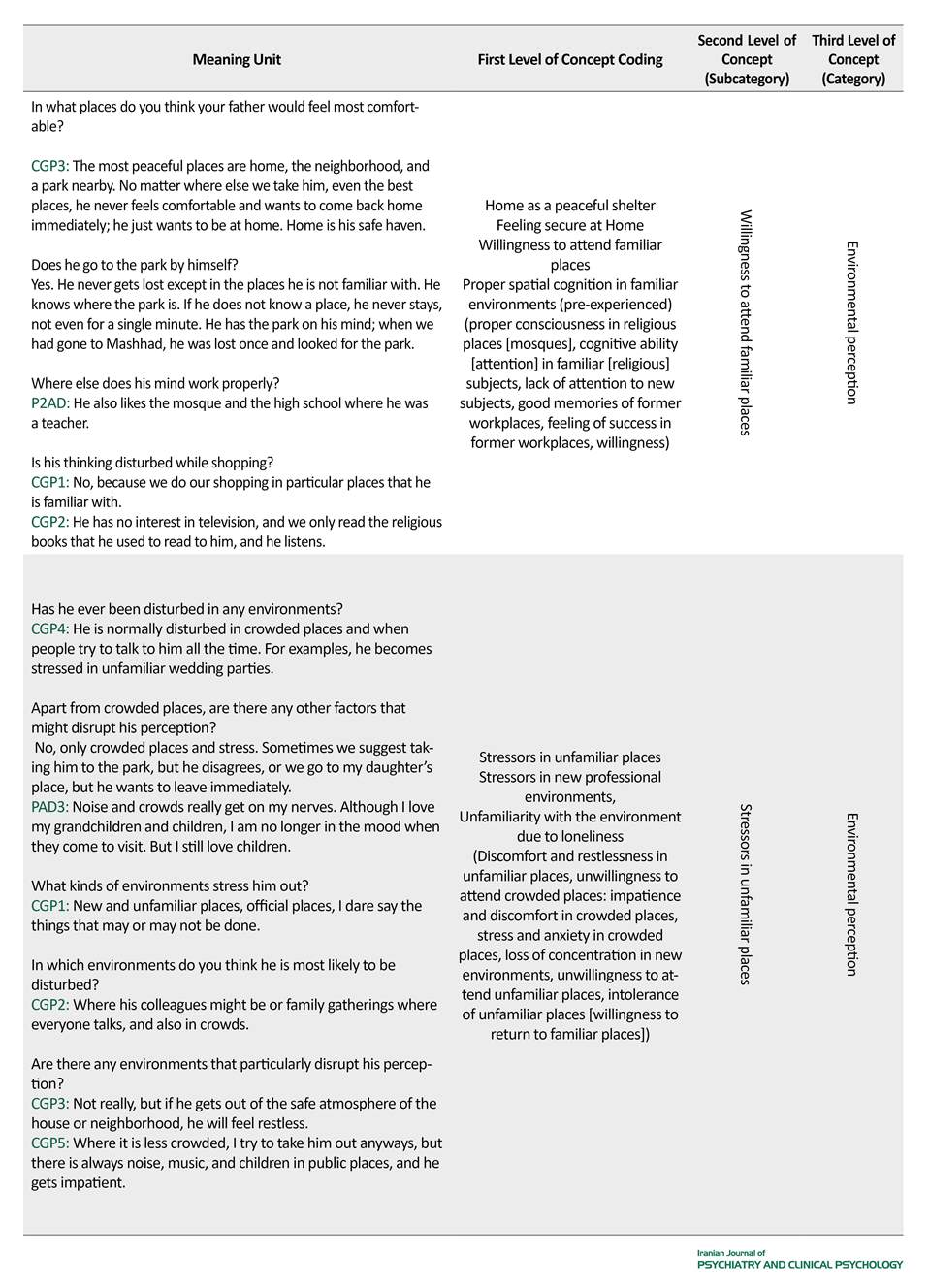

The main theme emerging from the interviews was the perceptions of patients with AD in a clinic in Tehran, Iran. The results of the content analysis of the interviews revealed the main perceptions of the patients with AD (Table 1). In addition, the inductive content analysis of the literature indicate that environmental perception has the most significant effect on the sense of place in these patients. Various aspects of the memory (e.g. spatial and topographic memory) were also observed to be effective in this regard (Table 2).

1. Introduction

Increased longevity and aging are among the most significant risk factors of catching Alzheimer Disease (AD). Recent studies have investigated the effects of physical and neuropsychological factors on the environmental perception of with the patients with AD. However, data are scarce on the associations between the main features of the physical environment and brain activities of Ad patients [1].

2. Method

This was a descriptive analytical study, which was performed using inductive content analysis. The final outcomes were the result of the interpretation and combination of semi-structured interviews with the people with dementia AD type and their caregivers and review of the literature in this regard. In addition, the similarities and differences between the qualitative physical features of the environment were assessed from the viewpoint of the patients with AD, their caregivers, and based on the literature review. The study data were collected through semi-structured interviews (15-30 minutes) using Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Functional Assessment Staging (FAST). In total, 9 participants were enrolled in the study, including four patients with AD and five caregivers. Furthermore, the required data were extracted from the current literature. The interviews were entitled Participants with ‘AD (PAD)’ and ‘Caregiver Participants (CGP)’.

3. Results

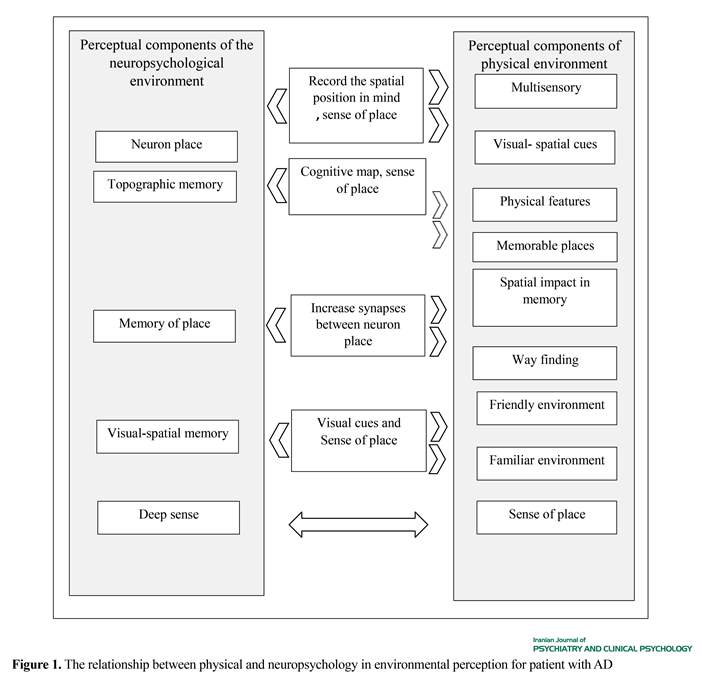

The main theme emerging from the interviews was the perceptions of patients with AD in a clinic in Tehran, Iran. The results of the content analysis of the interviews revealed the main perceptions of the patients with AD (Table 1). In addition, the inductive content analysis of the literature indicate that environmental perception has the most significant effect on the sense of place in these patients. Various aspects of the memory (e.g. spatial and topographic memory) were also observed to be effective in this regard (Table 2).

4. Discussion

The conceptual memory of the patient interferes with the memory of the spatial elements (place, light, and sound) [16]. Therefore, the fading of memories is accompanied by the loss of the sense of space and spatial awareness. With this background in mind, the patient may feel stressed in unfamiliar places due to the loss of the spatial memory. This finding is consistent with the contents of the live interviews in the present study.

The Parahippocampal Cortex (PHC) is activated more significantly while encountering new perspectives as compared to repetitive scenes and complex environments. According to the experiments, PHC shows a stronger response to spaces and places compared to the other visual stimulants [19]. According to Ziesel, spatial features play a key role in developing the spatial memories in patients with AD [20]. Furthermore, Lee and Wilson do not consider the spatial memory to be created by separate places, but rather, they believe that it is formed by the connections between a set of places [21]. Therefore, the contents obtained from the analysis of the interviews with the patients and their caregivers in the present study indicated the concept of “willingness to attend familiar places” and “creating proper spatial cognition in these environments” based on the identified features in the analysis.

The spatial memory of familiar places could remarkably improve the spatial memory in the elderly individuals [23], which is one of the similarities between the content analyses in the current research. According to Bongs, the sense of place is influenced by the physical space and spatial activities, which form the perceptions of individuals toward the environment [22]. This finding denotes another similarity between the results of the content analyses in our study. Therefore, prominent stimulants in the environment lead to the sustainability and stability of a strong sense of space in the hippocampus. Moreover, these stimulants develop specific memory pathways through the prominent spatial features. Likewise, the findings of Stenberg and Wilson demonstrated an association between the spatial memory and sense of space, so that the memories formed in the space influence the sense of place in individuals [18].

Environmental perceptions are involved in interpreting the perceptual-spatial data, laying the ground for the realization and organization of purposeful adaptive behaviors. Other benefits of such approaches include the reduction of stress and anxiety and overcoming memory deficiencies. Therefore, it could be concluded that stronger environmental perception is synonymous with the more frequent interactions of various aspects of physical environments and neuropsychological components. Recognition of the qualitative dimensions of the physical environment is essential to further influence neurological and brain functions, which in turn increase excitation and maintain attention. Enriching of the components of qualitative environmental perception of patients with AD with the help of the lived memory could play a pivotal role in their daily performance.

The conceptual memory of the patient interferes with the memory of the spatial elements (place, light, and sound) [16]. Therefore, the fading of memories is accompanied by the loss of the sense of space and spatial awareness. With this background in mind, the patient may feel stressed in unfamiliar places due to the loss of the spatial memory. This finding is consistent with the contents of the live interviews in the present study.

The Parahippocampal Cortex (PHC) is activated more significantly while encountering new perspectives as compared to repetitive scenes and complex environments. According to the experiments, PHC shows a stronger response to spaces and places compared to the other visual stimulants [19]. According to Ziesel, spatial features play a key role in developing the spatial memories in patients with AD [20]. Furthermore, Lee and Wilson do not consider the spatial memory to be created by separate places, but rather, they believe that it is formed by the connections between a set of places [21]. Therefore, the contents obtained from the analysis of the interviews with the patients and their caregivers in the present study indicated the concept of “willingness to attend familiar places” and “creating proper spatial cognition in these environments” based on the identified features in the analysis.

The spatial memory of familiar places could remarkably improve the spatial memory in the elderly individuals [23], which is one of the similarities between the content analyses in the current research. According to Bongs, the sense of place is influenced by the physical space and spatial activities, which form the perceptions of individuals toward the environment [22]. This finding denotes another similarity between the results of the content analyses in our study. Therefore, prominent stimulants in the environment lead to the sustainability and stability of a strong sense of space in the hippocampus. Moreover, these stimulants develop specific memory pathways through the prominent spatial features. Likewise, the findings of Stenberg and Wilson demonstrated an association between the spatial memory and sense of space, so that the memories formed in the space influence the sense of place in individuals [18].

Environmental perceptions are involved in interpreting the perceptual-spatial data, laying the ground for the realization and organization of purposeful adaptive behaviors. Other benefits of such approaches include the reduction of stress and anxiety and overcoming memory deficiencies. Therefore, it could be concluded that stronger environmental perception is synonymous with the more frequent interactions of various aspects of physical environments and neuropsychological components. Recognition of the qualitative dimensions of the physical environment is essential to further influence neurological and brain functions, which in turn increase excitation and maintain attention. Enriching of the components of qualitative environmental perception of patients with AD with the help of the lived memory could play a pivotal role in their daily performance.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research was extracted from the PhD. thesis of the first author in the School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology.

Authors contributions

The authors contributions is as follows: Conceptualization: Sima Mansoori, Farhang Mozaffar, and Mohsen Faizi; Investigation and analysis: Maryam Noroozian and Hassan Ashayeri; and editing and drafting: Sima Mansoori and Maryam Noroozian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate staff and participants of Yadman Clinic of Neurology for dementia AD type who helped us with this research.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information; Moreover, They were allowed to leave the study whenever they wish, and if desired, the results of the research would be available to them.

Funding

This research was extracted from the PhD. thesis of the first author in the School of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science and Technology.

Authors contributions

The authors contributions is as follows: Conceptualization: Sima Mansoori, Farhang Mozaffar, and Mohsen Faizi; Investigation and analysis: Maryam Noroozian and Hassan Ashayeri; and editing and drafting: Sima Mansoori and Maryam Noroozian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate staff and participants of Yadman Clinic of Neurology for dementia AD type who helped us with this research.

References

- Sung HC, Chang AM. Use of preferred music to decrease agitated behaviors in older people with dementia: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005; 14(9):1133-40. [DOI:10. 1111/j. 1365-2702. 2005. 01218. x] [PMID]

- Lawton MP. The physical environment of the person with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging & Mental Health. 2001; 5(supl. 1):56-64. [PMID]

- Mallgrave HF. The Architects Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture [ K Mardomi, S Ebrahimi, Persian trans.]. Tehran: Honar-E Memari Publication; 2017.

- Brocki KC, Bohlin G. Executive functions in children aged 6 to 13: A dimensional and developmental study. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2004; 26(2):571-93. [DOI:10. 1207/s15326942dn2602_3] [PMID]

- Kaplan S, Berman MG. Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010; 5(1):43-57. [DOI:10. 1177/1745691609356784] [PMID]

- Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1995; 15(3):169-82. [DOI:10. 1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2]

- Atchley P, Warden AC. The need of young adults to text now: Using delay discounting to assess informational choice. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 2012; 1(4):229-34. [DOI:10. 1016/j. jarmac. 2012. 09. 001]

- Biren, AB. Spatial manifestations of the human psyche. Paper presented at: 2014 ANFA Conference. 23 July 2014; San Diego, California.

- Pasqualini I, Blanke O. The architectonic self: own body perception and feelings in architectonic space. Cognitive Processing. 2012; 13: S27-S27.

- Sarmad Z, Bazargan A, Hejazi E. [Research methods in behavioral sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Agah; 2015.

- Heydari SH. [Introduction to research method in architecture (Persian)]. Tehran: Fekre Now; 2014.

- Cho JY, Lee EH. Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. The Qualitative Report. 2014; 19(32):1-20.

- Delavar, A. [Theoretical and practical principle of research in humanities and social sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Roshd; 2013.

- Javadi PS, Zendehbad A, Darabi F, Khosravifar S, Noroozian M. Development and implementation of Persian test of Elderly for Assessment of Cognition and Executive function (PEACE). Electronic Physician. 2015; 7(7):1549-56. [DOI:10. 19082/1549]

- Eberhard JP. Applying neuroscience to architecture. Neuron. 2009; 62(6):753-6. [DOI:10. 1016/j. neuron. 2009. 06. 001] [PMID]

- Sternberg EM. Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-Being. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2010.

- Armony J, Vuilleumier P. The Cambridge handbook of human affective neuroscience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [DOI:10. 1017/CBO9780511843716]

- Sternberg EM, Wilson MA. Neuroscience and architecture: Seeking common ground. Cell. 2006; 127(2):239-42. [DOI:10. 1016/j. cell. 2006. 10. 012] [PMID]

- Epstein R, Harris A, Stanley D, Kanwisher N. The para hippocampal place area: Recognition, navigation, or encoding? Neuron. 1999; 23(1):115-25. [DOI:10. 1016/S0896-6273(00)80758-8]

- Zeisel J. Evidence-based design in coordinated health treatment. Journal of Evidence-Based Design as Health Treatment. 2003; 35-43.

- Lee AK, Wilson MA. Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron. 2002; 36(6):1183-94. [DOI:10. 1016/S0896-6273(02)01096-6]

- Edelstein RS, Ghetti S, Quas JA, Goodman GS, Alexander KW, Redlich AD, et al. Individual differences in emotional memory: Adult attachment and long-term memory for child sexual abuse. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005; 31(11):1537-48. [DOI:10. 1177/0146167205277095] [PMID]

- Bangs L. Psychotic reactions and carburetor dung: The work of a legendary critic: Rock’N’Roll as literature and literature as Rock’N’Roll. New York: Anchor; 2013.

- Taube JS. Head direction cells and the neurophysiological basis for a sense of direction. Progress in Neurobiology. 1998; 55(3):225-56. [DOI:10. 1016/S0301-0082(98)00004-5]

- Konorski J. Integrative activity of the brain. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1967.

- Merriman NA, Ondřej J, Roudaia E, O’Sullivan C, Newell FN. Familiar environments enhance object and spatial memory in both younger and older adults. Experimental Brain Research. 2016; 234(6):1555-74. [DOI:10. 1007/s00221-016-4557-0] [PMID]

- Collier L, Truman J. Exploring the multi-sensory environment as a leisure resource for people with complex neurological disabilities. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008; 23(4):361-7. [PMID]

- Mansoori S, Faizi M, Ashayeri H. [New discourse in architecture; Architecture of Neuropsychology (Persian)]. Soffeh. 2018; 28(80):25-40.

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Psychiatry and Psychology

Received: 2018/02/27 | Accepted: 2020/03/10 | Published: 2020/03/10

Received: 2018/02/27 | Accepted: 2020/03/10 | Published: 2020/03/10

References

1. Sung HC, Chang AM. Use of preferred music to decrease agitated behaviors in older people with dementia: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005; 14(9):1133-40. [DOI:10. 1111/j. 1365-2702. 2005. 01218. x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01218.x] [PMID]

2. Lawton MP. The physical environment of the person with Alzheimer's disease. Aging & Mental Health. 2001; 5(supl. 1):56-64. [PMID] [DOI:10.1080/713650004] [PMID]

3. Mallgrave HF. The Architects Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture [ K Mardomi, S Ebrahimi, Persian trans.]. Tehran: Honar-E Memari Publication; 2017.

4. Brocki KC, Bohlin G. Executive functions in children aged 6 to 13: A dimensional and developmental study. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2004; 26(2):571-93. [DOI:10. 1207/s15326942dn2602_3] [PMID] [DOI:10.1207/s15326942dn2602_3] [PMID]

5. Kaplan S, Berman MG. Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010; 5(1):43-57. [DOI:10. 1177/1745691609356784] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/1745691609356784] [PMID]

6. Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1995; 15(3):169-82. [DOI:10. 1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2] [DOI:10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2]

7. Atchley P, Warden AC. The need of young adults to text now: Using delay discounting to assess informational choice. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 2012; 1(4):229-34. [DOI:10. 1016/j. jarmac. 2012. 09. 001] [DOI:10.1016/j.jarmac.2012.09.001]

8. Biren, AB. Spatial manifestations of the human psyche. Paper presented at: 2014 ANFA Conference. 23 July 2014; San Diego, California.

9. Pasqualini I, Blanke O. The architectonic self: own body perception and feelings in architectonic space. Cognitive Processing. 2012; 13: S27-S27.

10. Sarmad Z, Bazargan A, Hejazi E. [Research methods in behavioral sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Agah; 2015.

11. Heydari SH. [Introduction to research method in architecture (Persian)]. Tehran: Fekre Now; 2014.

12. Cho JY, Lee EH. Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. The Qualitative Report. 2014; 19(32):1-20.

13. Delavar, A. [Theoretical and practical principle of research in humanities and social sciences (Persian)]. Tehran: Roshd; 2013.

14. Javadi PS, Zendehbad A, Darabi F, Khosravifar S, Noroozian M. Development and implementation of Persian test of Elderly for Assessment of Cognition and Executive function (PEACE). Electronic Physician. 2015; 7(7):1549-56. [DOI:10. 19082/1549] [DOI:10.19082/1549] [PMID] [PMCID]

15. Eberhard JP. Applying neuroscience to architecture. Neuron. 2009; 62(6):753-6. [DOI:10. 1016/j. neuron. 2009. 06. 001] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.001] [PMID]

16. Sternberg EM. Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-Being. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2010.

17. Armony J, Vuilleumier P. The Cambridge handbook of human affective neuroscience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [DOI:10. 1017/CBO9780511843716] [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511843716]

18. Sternberg EM, Wilson MA. Neuroscience and architecture: Seeking common ground. Cell. 2006; 127(2):239-42. [DOI:10. 1016/j. cell. 2006. 10. 012] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.012] [PMID]

19. Epstein R, Harris A, Stanley D, Kanwisher N. The para hippocampal place area: Recognition, navigation, or encoding? Neuron. 1999; 23(1):115-25. [DOI:10. 1016/S0896-6273(00)80758-8] [DOI:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80758-8]

20. Zeisel J. Evidence-based design in coordinated health treatment. Journal of Evidence-Based Design as Health Treatment. 2003; 35-43.

21. Lee AK, Wilson MA. Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron. 2002; 36(6):1183-94. [DOI:10. 1016/S0896-6273(02)01096-6] [DOI:10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01096-6]

22. Edelstein RS, Ghetti S, Quas JA, Goodman GS, Alexander KW, Redlich AD, et al. Individual differences in emotional memory: Adult attachment and long-term memory for child sexual abuse. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005; 31(11):1537-48. [DOI:10. 1177/0146167205277095] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/0146167205277095] [PMID]

23. Bangs L. Psychotic reactions and carburetor dung: The work of a legendary critic: Rock'N'Roll as literature and literature as Rock'N'Roll. New York: Anchor; 2013.

24. Taube JS. Head direction cells and the neurophysiological basis for a sense of direction. Progress in Neurobiology. 1998; 55(3):225-56. [DOI:10. 1016/S0301-0082(98)00004-5] [DOI:10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00004-5]

25. Konorski J. Integrative activity of the brain. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1967.

26. Merriman NA, Ondřej J, Roudaia E, O'Sullivan C, Newell FN. Familiar environments enhance object and spatial memory in both younger and older adults. Experimental Brain Research. 2016; 234(6):1555-74. [DOI:10. 1007/s00221-016-4557-0] [PMID] [DOI:10.1007/s00221-016-4557-0] [PMID]

27. Collier L, Truman J. Exploring the multi-sensory environment as a leisure resource for people with complex neurological disabilities. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008; 23(4):361-7. [PMID] [PMID]

28. Mansoori S, Faizi M, Ashayeri H. [New discourse in architecture; Architecture of Neuropsychology (Persian)]. Soffeh. 2018; 28(80):25-40.

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |